A darkened Beirut shown during the summer of 2021, amid a worsening electricity crisis. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — The tipping point for Lebanon’s wobbling electricity sector came in 2021. After years of political malpractice, Lebanon’s oligarchs and their parliamentarians debated a no-win scenario.

They argued for either continuing the $1 billion-plus annual expenditures for a state utility that had contributed 46 percent of the country’s public debt since 1992, or trying to conserve Banque du Liban’s dwindling reserves and pass on electricity costs to consumers of generator power while pinning hopes on international help.

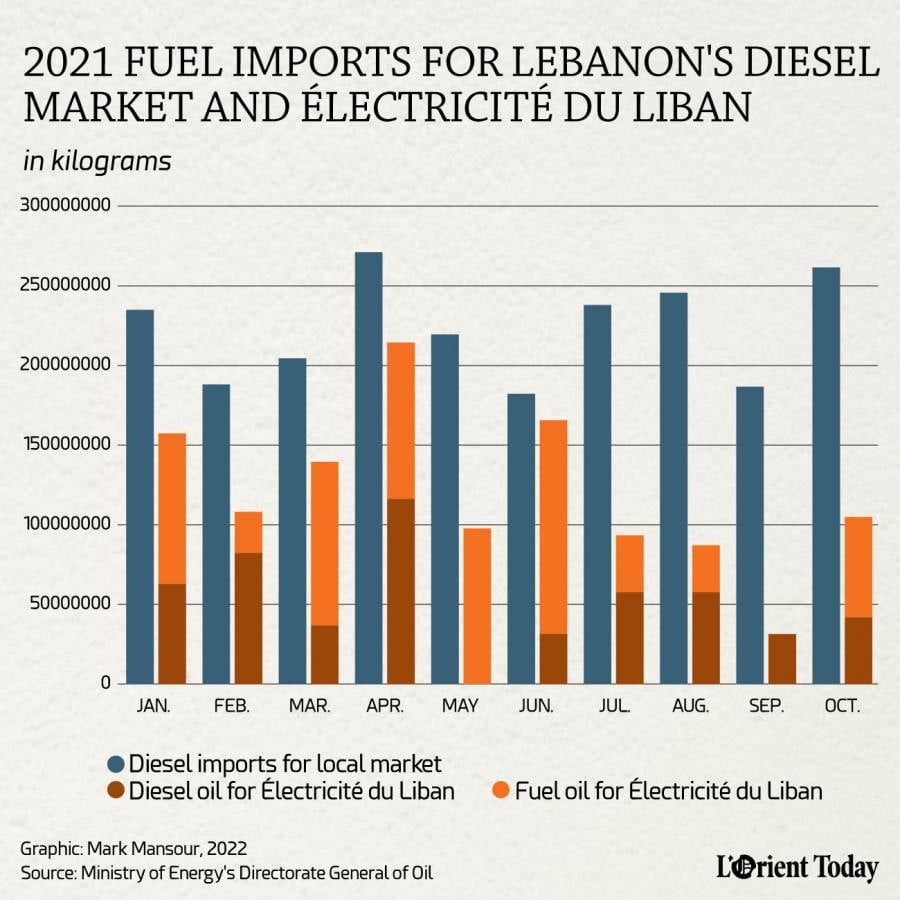

In the end, more money was spent in 2021 on diesel imports for back-up generators — much of it subsidized by the central bank — than for fuel for the loss-making public utility Électricité du Liban, L’Orient Today estimates from its analysis of fuel arrivals and Finance Ministry data. State electricity production plummeted, with rolling blackouts common, while an impoverished population had to dig deep in its pockets to pay for increasingly expensive generator coverage, especially after fuel subsidies were lifted at the end of the summer.

“Depending on the generators is detrimental to a country from a technical, operational, commercial, health and environmental perspective. It is national suicide,” Jessica Obeid, an independent energy consultant, told L’Orient Today.

The less electricity is supplied by the Lebanese state, the more expensive people’s power bills become, or, to reframe the paradox: the weaker the public electricity sector, the more business there is for private sector power providers and the importers and distributors fueling them.

While Lebanon’s road to electric ruin has been thoroughly analyzed and mapped, the fuel bill paid along the way for expensive and polluting back-up generators has been less scrutinized. According to an estimate calculated by L’Orient Today, approximately $10 billion has been spent on diesel imports for generators since 2010.

L’Orient Today calculated its figures using models for estimating Lebanon’s generator fuel consumption — employed in Lebanon’s official greenhouse gas emission reports and a World Bank study — as well as an analysis of detailed statistics of monthly fuel arrivals provided by the Energy Ministry's Directorate General of Oil (DGO), a price history of diesel cargoes on the Mediterranean market and EDL data.

To put the $10 billion figure in context, the Lebanese state has allocated $16.8 billion for EDL’s fuel purchases in that time. This means that generators have eaten up close to 40 percent of the county’s total fuel bill for electricity while producing about 33 percent of the country’s electricity. Lebanon has not gotten its money’s worth from the outlays on generator fuel.

“Diesel generator sets don’t have the same fuel efficiency as EDL, it’s not even something to be compared,” Marc Ayoub, coordinator of the Energy Policy and Security Program at the American University of Beirut, said.

The costs of the generator sector extend past the billions of dollars spent on fuel imports. Just as generators produce electricity at a more expensive rate than EDL’s power plants, they also are comparatively more polluting than the state power utility. EDL’s aging plants are not free from criticism over pollution either, with Greenpeace in 2018 ranking Jounieh as the fifth most air polluted city in the world, due in part to the nearby Zouk power plant that runs on fuel oil.

Still, a group of researchers at the American University of Beirut said in late October, “If EDL took over all the electricity coverage like it is supposed to, pollutant emissions would be lower than the generator alternative.”

The researchers warned that toxic emissions could increase by 300 percent amid the collapse of EDL’s power supply; causing an estimated annual increase of about 550 cancer cases while adding at least $8 million to the Lebanese people’s health bills.

Growing electrical deficits, surging diesel demand

Inefficient management of Lebanon’s electrical sector not only drove growing fiscal deficits in the past decade, it resulted in another widening deficit, an electrical one, that caused a decade-long surge in diesel imports for back-up generators.

Electricity deficits — or the difference between the supply provided by EDL and the demand for power by the population — serve as the backbone of models used in Lebanon’s emission updates and a World Bank report to estimate diesel consumption for generators.

From 2010, when then-Energy Minister Gebran Bassil unveiled an unrealized plan for 24-hour electricity, until 2019, when Lebanon's financial system started unraveling, Lebanon’s electricity deficit more than doubled, according to EDL’s production figures and demand estimates.

In that same time, the country’s endemic political gridlock helped scupper attempts to reform the electricity sector and EDL, build power plants needed to match growing demand, encourage renewable energy and facilitate cheaper fuel sources. The money Lebanon spent on renting offshore power barges since 2013 could have built three new land-based power plants.

Lebanon’s fleet of plants were fueled with diesel oil and heavy fuel oil, instead of cheaper and less polluting natural gas, supplied through opaque contracts, including one with Sonatrach, that would go on to cause scandal. When these contracts neared their end in 2020, authorities failed to tender new contracts, forcing the country to rely on more expensive options to procure fuel for EDL.

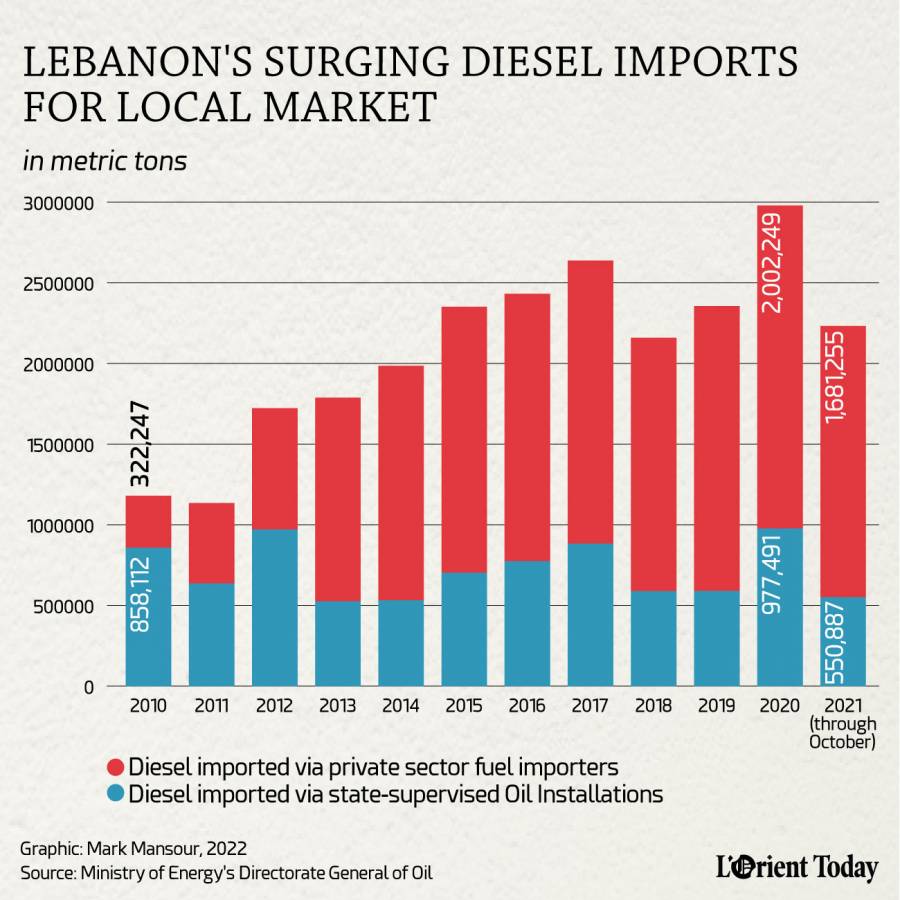

Amid the widening electricity deficits, annual diesel imports for the local Lebanese market skyrocketed, increasing from 1.18 million tons in 2010 to 2.35 million tons in 2019, according to DGO data. L’Orient Today estimates close to 15.2 million tons of imported diesel were used to fuel the country’s growing dependence on generators in that time.

While diesel fuel is used for other purposes — including heating, manufacturing, fishing and agriculture as well as road freight — generators take up the lion’s share of the fuel. The second-largest user of diesel, trucks, consumed 14 percent of diesel imports annually up to 2019, according to estimates in Lebanon’s emission reports and market surveys from the IPT fuel importing company reviewed by L’Orient Today.

Diesel for Lebanon’s local market arrives via two routes: either as imports tendered by the state-supervised Oil Installations in Tripoli and Zahrani, servicing clients from bakeries to municipalities, or as imports by the country’s 13 licensed private sector fuel importers, who maintain their own storage facilities.

The private sector firms, banded together in the Association of Petroleum Importing Companies (APIC) lobby, have serviced most of the growing diesel demand in recent years. In 2010, the companies imported 27 percent of the diesel entering Lebanon for the local market, a figure that rose to 75 percent by 2019.

The Lebanese state, “which imports diesel through the oil installations, cannot do anything to upend the way oil products are imported,” according to Noam Raydan, a Baghdad-based analyst focusing on energy in the Middle East.

“Attempting to change the current state of affairs implies threatening the cartel, which has been in place for decades and will remain there,” Raydan told L’Orient Today, referring to the private sector importers.

A 2020 study of Lebanon’s generator sector published by the World Bank brought up a paradox: while the fuel importers were among the “private sector actors who benefit the most from the existence of diesel generators,” they were among the least visible actors, with generator owners receiving the spotlight and anger.

“In terms of influence, fuel importers exert a high influence on the national level,” Ali Ahmad, the study’s author, wrote.

Ayoub, a critic of fuel importers, concurs, telling L’Orient Today that the country’s private sector fuel importers can count on several ways and channels to “indirectly influence political decision-making.”

Ahmad noted an “overlap between the shareholders of these companies and the political establishment in the country.” While this is most visible when politicians or their affiliates own shares in the companies, he wrote in his report, “there is a less pronounced overlap that is channeled through donations to political and religious institutions, philanthropy work and nepotism.”

In one leading example of the nexus of politics and fuel importing, COGICO — which had the third-highest market share for diesel among APIC’s members in 2018 — is part owned by Progressive Socialist Party leader Walid Joumblatt.

A recent entrant in Lebanon’s fuel market as a state contractor, UAE-based ZR Energy DMCC, made numerous appearances as a supporting character in the narrative of Lebanon’s electrical breakdown and diesel boom in the past two years.

Descent into darkness

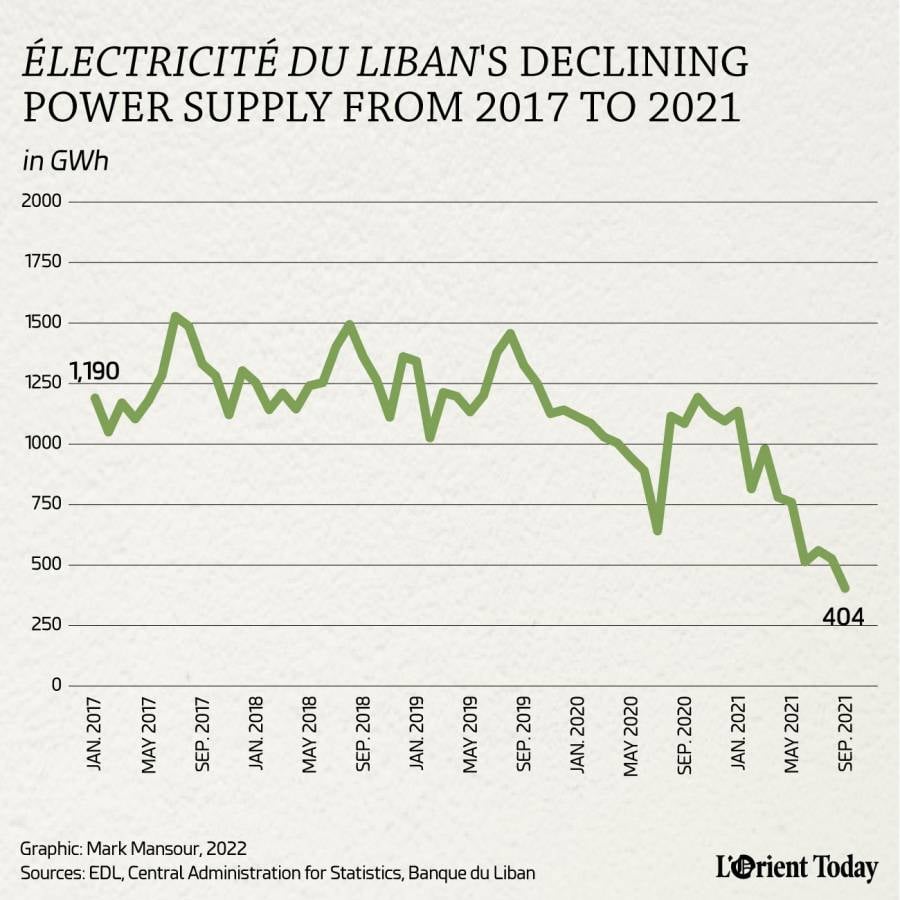

EDL’s monthly electricity production peaked in July 2017, with year-on-year supply declining since; first gradually, and then precipitously as Lebanon made international headlines with a complete shutdown of state power plants on Oct. 9, 2021.

From 2005 through 2020, Lebanon’s power plants relied mostly on fuel oil and diesel oil provided under opaque contracts with Algeria’s Sonatrach and the Kuwait Petroleum Corporation. One of these shipments, in March 2020, caused a legal scandal that ensnared state officials as well as a little-known fuel importer, and helped precipitate rolling blackouts.

In April 2020, Mount Lebanon’s chief prosecutor Ghada Aoun, widely seen as close to the Free Patriotic Movement, kicked-off legal action after a tanker sent under Lebanon’s contract with Sonatrach delivered off-specification fuel for EDL. Among those arrested in the case, which alleged bribery of public officials, fraud and shady deals, was Sonatrach’s reported local representative.

Sonatrach, which denied wrongdoing, informed Lebanon on June 9, 2020 that it would not renew its contract at year’s end and claimed the country was violating its agreements. From June to July 2020, Sonatrach's deliveries of fuel oil and diesel oil for EDL plummeted, according to DGO data, leading to a sharp drop in EDL production.

The tainted fuel at the center of the scandal was delivered by ZR Energy DMCC, according to legal proceedings in the case, which said the Dubai-registered firm was subcontracting for a Sonatrach subsidiary since 2017. ZR Energy DMCC denied committing any crimes.

The firm accused the prosecution of being politically motivated, and said it was the victim of a “cynical and sinister power struggle within Lebanon.” The company and its owner, Ibrahim Zaouk, are currently awaiting trial in the case.

ZR Energy DMCC’s connections to Lebanon’s electricity sector go beyond its deliveries for Sonatrach and diesel provisions for the country’s local market. The firm’s owner, Zaouk, served as one of the directors of AVAX DAPP II (Lebanon) SAL, a firm established in 2019 to develop a long-stalled project for a new power plant in Deir Ammar, according to corporate documents reviewed by L’Orient Today.

Other directors on the board of the power plant company included Alaa al-Khawaja, the chairman of BankMed, and Raymond Rahme, an owner of the ZR Group SAL Holding company, which is facing charges in the tainted fuel scandal alongside ZR Energy DMCC. Zaouk and Rahme resigned from the board in July 2020, while the plant development project never got off the ground.

While ZR Group SAL Holding insists that it was not involved with ZR Energy DMCC’s fuel imports, testimony in the tainted fuel investigation alleges otherwise. During the initial probe, a finance employee at ZR Group SAL Holding told the investigating judge that the company had used its relations with Fransabank, Banque Libano-Française, Bank of Beirut, Bank Audi and BankMed to open letters of credit on behalf of ZR Energy DMCC, according to a copy of the preliminary charges seen by L’Orient Today.

The judiciary dropped the money laundering charges brought against ZR Group SAL Holding and ZR Energy DMCC in the tainted fuel scandal, dashing any attempts to lift banking secrecy on the companies and other defendants, according to a report from Legal Agenda, a Beirut-based legal advocacy organization.

“This case constitutes another use of banking secrecy as a magic seal to undermine accountability,” the report added.

Despite being embroiled in legal challenges, ZR Energy DMCC landed a new state tender to provide diesel for the local market on Aug. 22, 2020, the first of eight diesel tenders it would win in the coming months as demand for generator fuel grew.

Lebanon imported more diesel in 2020 for the local market than in any previous year — just shy of 3 million tons — with private sector fuel importers holding 67 percent of the market share. According to L’Orient Today’s calculations, based on generators covering 60 percent of EDL’s downtime, 1.8 million tons of diesel were used by generators that year.

This figure rises to 2.4 million tons if the country’s generators covered 80 percent of EDL’s power cuts, the same percentage assumed by Lebanon’s greenhouse gas emission reports before the country’s electric downturn in 2020.

The country’s second-largest user of diesel, heavy trucks for freight, would have consumed less of the fuel than in previous years due to COVID-19 lockdowns and economic downturn, according to Marc Haddad, an associate professor of engineering at the Lebanese American University who has authored studies on the transport sector’s greenhouse gas emissions. In 2019, trucks used 496,000 tons of diesel, according to IPT’s market survey.

One set of diesel end-users was widely seen as growing in 2020: smugglers and hoarders of the subsidized fuel, who would gain even more attention as the fuel and electricity crisis worsened the following year.

Blackout

2021 was a dark year, literally and figuratively, for Lebanon: EDL was left bereft of fuel, while diesel for the private sector flooded into the country. The growing electrical and fuel crisis took on international dimensions after Hezbollah became the newest player in the diesel market.

With Lebanon’s US dollar reserves continuing to dwindle at the beginning of 2021, the state resorted to the costlier spot market to source fuel for EDL after its contracts with Sonatrach and KPC came to an end. ZR Energy DMCC on Jan. 20 won the first of these supply tenders, which were paid for with funds left over from the previous year’s $1 billion treasury advance to EDL.

What remained of EDL’s funds was being spent more and more quickly, with global fuel prices surging over 30 percent in the first quarter of 2021. On Feb. 23, Energy Minister Raymond Ghajjar, widely perceived as affiliated with the FPM, warned the state utility would run out of money in a month's time.

The stage was set for a political brawl in Parliament over the provision of more funding for EDL’s fuel purchases, with the FPM asking for $1 billion while its rivals balked at the proposal. The number was slashed to $200 million — a figure proposed by the Amal Movement, and passed by Parliament on Mar. 29 over the objections of the Progressive Socialist Party and Lebanese Forces — which both argued against using further BDL reserves.

“The history of Lebanon in times of crises shows that political wrangling over finances to import fuel is not something unusual, and Lebanese have seen it before,” Raydan said, citing the example of a debate in 1987 over gasoline imports.

Obeid said that the debate followed “the long-term mode of operation of the sector of kicking the can and implementing quick fixes, rather than a sustainable solution.”

“The periodic treasury transfers to EDL without serious reforms and a sustainable solution that aims at providing the cheapest electricity provision while maximizing the reliance on domestic natural resources, have constantly aimed at maintaining the status quo and consequently, the vested interests of the dominant political powers,” she told L’Orient Today.

Even after it started tapping into the new treasury advance, EDL was procuring far less fuel than in previous years. It would take until September for Lebanon to start receiving fuel via a convoluted and opaque swap mechanism with Iraq, and these consignments would only cover a fraction of EDL’s needs.

Up to Nov. 7, Lebanon allocated EDL $525.6 million in treasury advances, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Finance told L’Orient Today. Through September, when subsidies on fuel came to an end, approximately $700 million was spent on fuel for generators, according to L’Orient Today’s estimate, based on generators covering a mere 50 percent of EDL’s downtime.

With EDL’s electricity production plummeting through the summer, demand for back-up generator power spiked. Generator owners resorted to rationing amid diesel shortages, and their syndicate even called on the state to ensure more EDL supply.

Diesel imports through October 2021 were just slightly down from the previous year’s record numbers, with a monthly average of 223.2 million kilograms, compared to 248.3 million kilograms in the same time period in 2020.

As temperatures soared in August and fuel shortages caused increasing chaos, the Lebanese Army launched a series of highly publicized busts against the hoarding and smuggling to Syria of diesel and gasoline. The raids were spurred on, in part, by an explosion on Aug. 15 at a confiscated fuel depot in the Akkar town of Tleil that killed more than 30 people.

From Aug. 14 to the end of the month, the Lebanese Army, according to its statements, seized around 1.8 million kilograms of diesel. This figure amounted to a tiny portion of imported diesel: the previous month, 237.9 million kilograms of diesel entered Lebanon for the local market, according to DGO data.

Hezbollah entered the fray of the fuel crisis on Aug. 19, when the organization’s leader announced a diesel shipment had set sail from Iran. The US — which sanctions Iranian fuel exports and Hezbollah — swung into action soon after, backing a plan to supply Lebanon with Egyptian natural gas and Jordanian electricity moved via Syria with World Bank financing.

Hezollah’s promised vessel, FAXON, arrived off the coast of Syria in mid-September laden with 33 million kilograms of diesel, according to TankerTrackers.com, a firm following oil shipments. The organization’s fleet of trucks started delivering the diesel overland from Syria to northeastern Lebanon on Sept. 16. It would take until Oct. 10 for Hezbollah to move all of the FAXON’s cargo to Lebanon.

Hezbollah’s consignments in those four weeks amounted to a little over 10 percent of Lebanon’s diesel market share. The first phase of its diesel distribution program wrapped up Nov. 1, with another for fuel for home heating starting Nov. 29. Two other vessels, each laden with approximately 33 million kilograms of diesel, had arrived for Hezbollah off the Syrian coast after the FAXON, according to TankerTrackers.com.

The US-backed plan, meanwhile, has remained mired in preparations as Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and Syria hammer out the arrangements, while different players in Washington have wrangled over whether the deal should be exempted from US sanctions on Syria. Premier Najib Mikati’s cabinet, formed Sep. 10, set a number of ambitious electricity sector goals in its mission statement, but so far has been struggling to achieve its immediate objective of “securing electricity for citizens as soon as possible.”

On Sep. 29, the new cabinet unlocked a $100 million loan from the central bank to fund more fuel tenders for EDL. On Oct. 14, two days after what would prove to be his cabinet’s last meeting in 2021, Mikati vowed the country would have 10-12 hours of electricity a day after New Year’s. The goal was not met.

At year’s end, EDL’s capacity fluctuated between a scant 370 to 610 megawatts, an engineer at the utility told L'Orient-Le Jour, or between approximately 3 to 6 hours a day. Generator prices skyrocketed while consumption of diesel has not dropped like that of other fuels after the cutting of subsidies.

With parliamentary elections — scheduled for May 15 — around the corner, diesel appears to have become yet another tool in Lebanese rulers’ patronage systems. Apart from the Iranian fuel distributed by Hezbollah, for instance, MP Ibrahim Kanaan (FPM/Metn) donated 10 tons of fuel for generators to the municipality of Baskinta on Jan. 6.

“The distribution of diesel for generators is also being used for political gains, and we're seeing MPs and wannabe MPs openly bragging about supplying towns with electricity,” Obeid said.

“How do these politicians have access to diesel, what is the role of an MP and what is the role of the public institutions? The mandates have become so blurry which also aims to avoid accountability,” the consultant added.