Devastated by the explosion at the port of Beirut on Aug. 4, 2020, the headquarters of Electricité du Liban is a symbol of the dilapidated state of the public electricity sector in Lebanon. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

With a smirk on his face, he begins telling his story: “So, one day I got a call from the police.”

At his side, his colleague is already giggling at the memory of this ludicrous anecdote.

“I showed up at the police station, received by a youngster without a diploma, but in uniform,” Hani*, an engineer at the Jamhour power station in Mount Lebanon, tells L’Orient-Le Jour.

The surgical mask that covers a good part of his face fails to hide the bags under his eyes. He finally cuts to the chase, blurting out, “Someone had reported me because they did not have enough electricity.”

Everyone bursts into laughter.

In a country that has been grappling with a crisis for more than two years, sarcasm has become the best means of survival.

The national currency and fuel shortage crisis has resulted in long hours of power outages, with only two to three hours a day of state electricity provided by Électricité du Liban.

Taking on a more serious tone, Hani fidgets with his phone and opens his messages.

“We are being insulted all day long,” he says as he scrolls through dozens of messages from people who demand more hours of power in crude terms.

Worn out citizens, uncaring authorities – “Everyone spits on us,” he says.

Hani adds with a mix of indignation and dismay, “We are being blamed for everything, but no one is giving us the means to generate electricity. And without us, there wouldn’t be a second of state electricity in this country!”

On the upper part of Beirut, in this EDL station, the situation feels like something more befitting a much earlier time.

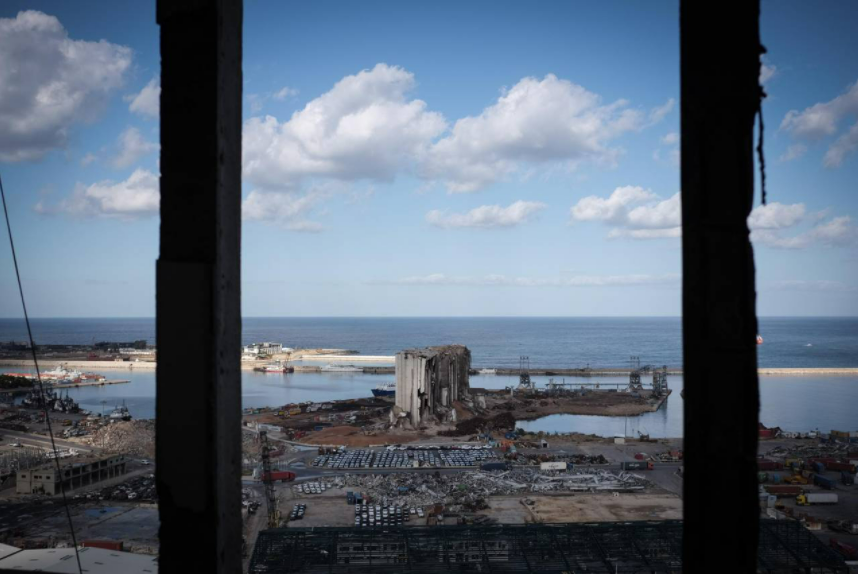

In Jamhour, a small team took over control of the national grid after the destruction of the Beirut headquarters in the aftermath of the 2020 explosion. The structure of the headquarter building in Mar Mikhael, overlooking the port, was the only thing that survived the blast. Inside, however, everything was blown away except the foundations.

While the port silos protected part of the capital, the 13-story EDL headquarters “saved the Achrafieh neighborhood from being razed to the ground,” Rita*, an EDL employee, tells L’Orient-Le Jour.

Built in the 1960s, the reinforced concrete building was designed to withstand a magnitude 9 earthquake, according to EDL management. Shortly after the tragedy, experts calculated that the Beirut port explosion had a 3.3 magnitude.

The national electricity grid control center, located on the 9th floor of the Electricité du Liban building in Beirut, was completely destroyed on Aug. 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

The national electricity grid control center, located on the 9th floor of the Electricité du Liban building in Beirut, was completely destroyed on Aug. 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

“Inside the building, two people died on Aug. 4, 2020, and 21 were injured,” Rita says. On that day, the lockdown had been partially lifted, while the world was still only in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The offices were open but “working hours had been changed and we were finishing earlier,” she recalls. If it weren’t for this, “more potential customers and associates, hundreds of employees would have been present in the premises,” Rita adds.

After a moment of reflection, the young woman turns to the building, her eyes widened in fear. As if scared to utter the words out loud, she murmurs, “Can you imagine the massacre?”

The 13th floor of the building offers a panoramic view worthy of a postcard, but also a bird’s eye view of the port.

“We’re right on top,” EDL director Kamal Hayek says. Tuesday, Aug. 4, 2020, was the eve of a board meeting at the company.

At the end of that summer day, Marie Tawk, a longtime assistant to the director and head of communications, was on the 13th floor putting the finishing touches to the meeting’s presentation with an external consultant, Claudia Lakkis. This would be the last thing they did.

Zeina Chamoun, the third EDL victim to have died in the explosion, was in her home, a few steps from the company.

“They were conscientious people,” Hayek says. On the day of the tragedy, he was finishing some administrative tasks with the director of legal affairs at around 6 p.m.

Despite the fire that was raging in the port opposite the EDL building and the ominous turn of events on the evening of Aug. 4, the work at the company continued.

When the first explosion rang out, “I told my colleagues to stay away from the windows and go down the hall. I just sensed another explosion coming,” the director says. A few seconds later, he said, “I felt my body was imploding.”

Stuck under the rubble, Hayek barely regained consciousness and was unable to move.

“Blood was flowing from my mouth, and I feared that I might have internal bleeding.”

It took more than an hour for other workers to climb up to them, and a few more hours for rescuers to pull out the injured from under the rubble and transport them to the hospital.

Hayek suffered a punctured lung and six broken ribs. He returned to work two months later. In his office, he keeps a picture of Marie Tawk and Zeina Chamoun.

The director of Electricity of Lebanon, Kamal Hayek, works in one of the containers on the forecourt of the Beirut headquarters. He was seriously injured in the double explosion of Aug. 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

The director of Electricity of Lebanon, Kamal Hayek, works in one of the containers on the forecourt of the Beirut headquarters. He was seriously injured in the double explosion of Aug. 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

‘We work like refugees’

In the aftermath of the explosion, the 750 EDL employees at the headquarters building were transferred to other offices and power stations across the country.

Two hundred people still work on alternate days in containers installed in the courtyard of the Beirut headquarters, a stone’s throw from the highway. The insides of these metal structures look like numbered cells straight out of an American prison. In the summer, they are too hot, and in the winter, extremely cold. When it rains, they are flooded.

“We work like refugees,” an employee says as he passes by, while the EDL director laments the fact that “social distancing is impossible here.”

At nightfall, the place is creepy. On one side, the white silhouette of the gutted silos pierces the darkness, and on the other stands the dark block of the EDL building.

“I always ask someone to walk me to my car,” Rita says.

The several-floor parking lot is located under the building. It is dark and humid there. A cat walks past a mechanic who is smoking a cigarette on the side of the driveway that leads to the company cars, most of them are now only good for scrap, smashed by the explosion.

The place looks surreal, as if taken from the set of a bad sci-fi movie. Only a portrait of President Michel Aoun that stands, six feet underground, behind the mechanic brings the onlooker back to the real world in Beirut.

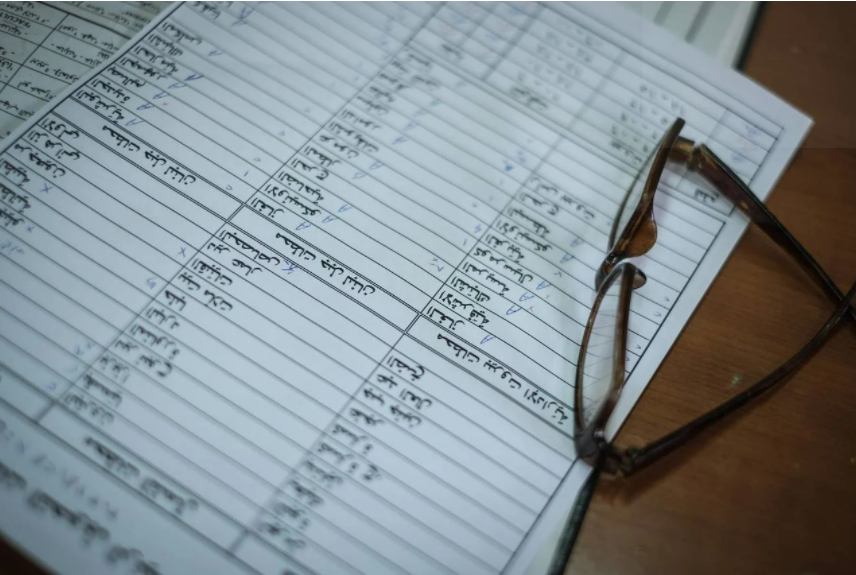

Further on, seemingly new grids divide the space in two. A dim yellowish light emanating from the parking lot casts a man’s shadow on the wall. Caught between two rows of metal cabinets, Samir*, the archivist was delighted, after a few moments of suspicion, to explain his system of file organization — it’s not every day he gets asked about it.

Caught between two rows of metal cabinets, the archivist managing complaints addressed to EDL and those of EDL targeting subscribers classifies the 34,000 files that have descended from the 12th floor to the underground car park since the double explosion of Aug. 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

Caught between two rows of metal cabinets, the archivist managing complaints addressed to EDL and those of EDL targeting subscribers classifies the 34,000 files that have descended from the 12th floor to the underground car park since the double explosion of Aug. 4, 2020. (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

“You are in the legal affairs department here,” he says proudly, presenting himself as the sole head of the section handling complaints to EDL and those EDL has made against subscribers.

“I have been working alone for 20 years. I prefer it this way,” Samir says.

Some “34,ooo files” were brought down from the 12th floor, the oldest of which date back to 1967, and are categorized in the lockers. Some files were lost in the aftermath of the explosion or in the war. “But only a few,” he reassures.

In fact, he said, “over the years I have been digitizing the files.”

A few steps away, in a room converted into an office, wedged between the garage and a flooded toilet, he demonstrates his digitization.

In a few clicks, he manages to pull out a file from 1970. Only Samir knows how to use the system to access the archives but assures L’Orient-Le Jour that if anything is to happen to him, everyone can have access to this computer.

‘We are not allowed to get rid of them’

Rare are the die-hard employees who still work in the EDL building. A resident of the neighborhood recalls seeing a light on there in the evening. One of the elevators was repaired in the building after the explosion — a mission that had to be done to take down the pieces of equipment that are still functional and the documents necessary for the institution to run.

The elevator, however, is not automatic. There is a landline by the door to call the guard and ask him to start it.

On the third floor, at the bend of a gaping staircase, in the midst of dismantled sections of wall and doors off their hinges, a man sits at his desk.

Through the window, the stillness of the silos once again catches the eye. Against the wall, the metal cabinets are still pierced with shards of glass.

Every day, Paul*, an official in the billing department, walks through the ruins of the workplace where he has been employed for more than 50 years.

Many employees have cleaned their own offices and plastered plastic sheeting or wooden planks in place of blown windows.

Paul managed to arrange his little office in such a way to be able to settle back in. He tells L’Orient-Le Jour that he will retire in the coming few days, and with pride says that he was here when EDL acquired one of the first computers imported to the Middle East in the 1960s. Back then, the Lebanese army came here to do their accounts after working hours, when the EDL employees were gone.

“The machine is still in the basement,” he says.

While the billing center has been relocated to the Zouk Mosbeh power plant in Kesrouan, Paul has remained at the Beirut office because, like most workers, he no longer can afford to pay for gas to drive there, as the fuel prices soared with the depreciation of the national currency and the ending of fuel subsidies by Banque du Liban.

As a result of the lira depreciation, EDL employees’ salaries were slashed. Looking at the heaps of debris and scrap littering the building’s courtyard, Rita says jokingly, “We were not allowed to get rid of them. Maybe they want to resell them to pay us!”

Meanwhile, Hayek confirms that calls for tenders for the resale of these materials will be launched, “in accordance with the institution’s internal regulations,” once the exchange rate stops fluctuating.

EDL continues to pay its employees at the officially pegged rate of LL1,507.5 to the dollar. The company’s lowest monthly wage package amounts to LL1 million, which is now worth about $30 on the parallel market.

And with the price of 20 liters of petrol well above LL300,000, “the majority of employees work from home,” explains Michel*, the head of the billing center.

‘People only remember the outages’

Working remotely is not an option for the technicians at the electrical relay station in Jamhour.

“Holidays? Strikes? Lockdowns due to the pandemic? These concepts are strange to us here,” Pierre, * a technician, says before heading toward a large instrument panel. Following his colleagues’ instructions, he turns two cranks. One to the right, and one to the left.

It is 10 o'clock sharp in the morning. At this very moment, some residents somewhere in Lebanon just received state electricity, while others just lost it.

As winter sets in, what is left of the state electricity is run at this plant, which the Israeli army destroyed on three occasions. More precisely, it is run from this room, which lacks a heating system. On the wall, there is a creased calendar for 2017.

A technician at the Jamhour electrical relay station (Mont-Liban), promoted to focal point for the management of the national grid shortly after August 4, 2020, turns the cranks which activate and deactivate the current distribution outputs divided by regions. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

A technician at the Jamhour electrical relay station (Mont-Liban), promoted to focal point for the management of the national grid shortly after August 4, 2020, turns the cranks which activate and deactivate the current distribution outputs divided by regions. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

“There is no country in the world that manages its electricity this way and there is no expert on earth who can maintain ongoing balance with such a grid,” Hani, the engineer, says. “Power production should exceed consumption, as explained in the books. Here, it is the other way around … And at extremely varying rates!” he adds, as his colleagues nod in consent.

Two of them hold the telephone handset to their ears. In front of them, a frequency meter is placed on a television that is turned off. The phone was ringing every 10 to 15 minutes. The same gestures and the same questions are repeated every time, but never the same answers.

As they report the amount of electricity (in megawatts) generated in real time by the country’s power plants on the printed lists, they take a quick look at the frequency meter, which must necessarily indicate a 50 hertz frequency, before they tell their colleague which outputs distribution to enable and disable for each area.

In general, in order to ensure a continuous power distribution management in the country and resolve the constant problems that arise in relation to it, “10 people take turns, working 24/7. The managers can be sought at all times,” Hani says.

In the control center at the headquarters in Beirut, everything was computerized. Today, everything related to this “complex” operation is done by phone and manually. If a balance between consumption and production is not achieved when it is time to switch on, a blackout ensues.

Outages became more frequent over the past year, in light of the ongoing power instability in the grid. But, thanks to experience, “we can now restore power in just a few hours when there is a total blackout, while it took us an entire day to fix it in the past,” the engineer says as he smiles.

On Aug. 4, 2020, “it took us 15 minutes to restore power after the explosion,” he says. Zaher Roukos and Georges Azzi were on duty at the control center in Beirut that day. They suffered serious wounds. Shortly before 6 p.m., one of their supervisors had left the headquarters.

As soon as he grasped what had just happened, he asked two technicians in a relay station close to Beirut to restart and maintain the grid — albeit partially. “But no one talks about it. People only remember power outages,” he says.

The port of Beirut, blown away by the explosions of Aug. 4, 2020, is located directly in front of the Electricité du Liban building. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

The port of Beirut, blown away by the explosions of Aug. 4, 2020, is located directly in front of the Electricité du Liban building. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

The power plant in Jamhour, which serves as a connection point in managing the national grid, is now in charge of adjusting voltage levels supplied by the country’s power plants. A high voltage current, ranging from 66 to 150 kilovolts, arrives at the substation, which transforms and redistributes it, through the country’s 70 relays, in medium voltage, ranging from 1 to 36 kilovolts. The 1,000 distribution outputs, 30 of which are located in Jamhour and feed a part of Beirut, then provide low-voltage electricity to residents.

In order to ensure a stable grid, “balance needs to be maintained between the current transmitted through an output and its consumption load,” the engineer says. According to him, ideally, power generation needs to vary from 3,000 to 3,500 megawatts to be able to meet the country’s demand for electricity, he says.

A few days ago, “production was a bit over 500 megawatts,” before the stock of some fuel oil came to an end. “Today, I only have 370 megawatts to be distributed across the country,” Hani says. As the end of year holidays approached, “we finally managed to stabilize the grid with nearly 613 megawatts produced with fuel imports from Iraq, thanks to $100 million in credit approved [by BDL] in the past few months,” EDL director says.

While power generation is still far too low, EDL technicians are required to keep their eyes and ears open at all times and ensure that all and sundry get a minimum supply.

“We are trying to give more [supply hours] in the evening. Sometimes in the middle of the night. To take over from the generators, and because consumption is lower at night,” Hani says.

The engineer brushes away with his hand accusations of favoring one area over another. “Some are just lucky enough to be on the same line as a water department, for instance,” he explains.

In fact, “the Beirut International Airport, the ports of Beirut and Tripoli, the water pumps and a number of ministerial and public establishments need EDL electricity to operate,” not the neighborhood supply providers, which have become a burden on any resident who does not want to live in the dark in Lebanon, Kamal Hayek says.

At the Jamhour electric relay station (Mount Lebanon), promoted as a liaison point for the management of the national network, the daily quantities of megawatts produced by the power plants are supervised by telephone and by hand 24 hours a day. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

At the Jamhour electric relay station (Mount Lebanon), promoted as a liaison point for the management of the national network, the daily quantities of megawatts produced by the power plants are supervised by telephone and by hand 24 hours a day. (Credit: João Sousa./OLJ)

‘We are not behind the delay’

The premises, including the power plants is Jamhour and Zouk, and the containers in Beirut, serve as constant reminder of the state of desolation of Lebanon’s energy sector which, combines all the evils that dragged the country to ruin ̶ corruption, bad governance, lack of reforms and political cronyism.

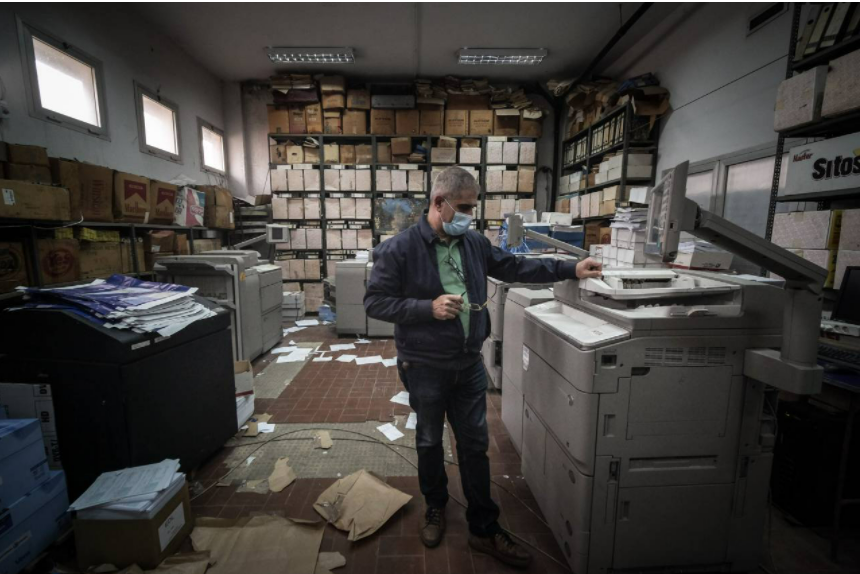

In the room where the bills are issued, relocated to the administrative offices in the Zouk power plant, moisture soaks into the walls and ceilings and a metal board had to be placed to keep the water leak away from the computer server, which relies on a generator to keep running.

“This backup server helped us recover, in three days, the department’s data after Aug. 4,” Michel, the department head, says.

On the floor below, copiers and printers for printing invoices are housed in a storeroom. Inside, dozens of papers are scattered on the floor; shelves are lopsided; dusty boxes and binders yellowed by the years are piled up to the ceiling; a car inner tube replaces the missing part of a water pipe; a piece of board patches a hole in the wall.

The photocopiers and printers used to edit Electricité du Liban invoices are installed in a storage room of the invoicing center relocated to the Zouk Mosbeh power plant (Kesrouan). (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

The photocopiers and printers used to edit Electricité du Liban invoices are installed in a storage room of the invoicing center relocated to the Zouk Mosbeh power plant (Kesrouan). (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

The total absence of state investment in EDL is not a new practice, but “the thievery, protected by some politicians, and the Lebanese lira devaluation are holding up the purchase of new equipment, even that of printer ink or computer software licenses, which are priced in dollars,” Michel explains.

However, “we’re pretty much the only office generating money for EDL,” Michel says, as he inexpertly tries to hide the irony of his words in the midst of this bleak picture. Although “the repatriation of files has been slowed down by the fuel problems that our employees are facing and by the fact that we only have one computer for the data registration process, we are not behind the delay related to the billing!” he says, at a time when some households are currently receiving monthly invoices dating from 2019.

“Our role is to issue the invoices based on some criteria, but the companies in charge of the [payment] collection are taking time in conducting their mission,” he says, and added that sometimes they don’t hear from them “for months.” “And they blame us for it,” he says. This is while EDL’s subcontractors level the same accusation against the institution.

The strikes that EDL workers’ union went on in the past few weeks were partially against these companies. For its president, Charbel Saleh, extending the prerogatives of the private companies, which were appointed to run, maintain and modernize the grid in 2012 under the tenure of former Energy Minister Gebran Bassil, is one of the main complaints he submitted to the cabinet, as well as the EDL workers’ working conditions and rehabilitation of the headquarters in Beirut.

“The call for tenders for the reconstruction of the building was supposed to be made, but the Energy Ministry plunged into a deafening silence all of a sudden,” he says. The EDL director confirmed these remarks, but refused to give any details about the cost. Speaking to L’Orient-Le Jour, a third-party source familiar with the file says the rehabilitation cost is estimated at “$18 million” — a sum that a bankrupt state cannot pay out on its own and that an institution in decline will need to go cap in hand to foreign funds to secure.

Stuck between the silos gutted by the double explosion at the port of Beirut on Aug. 4, 2020 and the completely devastated Electricité du Liban headquarters, construction containers now serve as offices for some 200 employees. (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

Stuck between the silos gutted by the double explosion at the port of Beirut on Aug. 4, 2020 and the completely devastated Electricité du Liban headquarters, construction containers now serve as offices for some 200 employees. (Credit: João Sousa/OLJ)

‘We are just like everybody else’

In the deserted part of the substation in Jamhour, the thunderstorms’ grumbles and growls are heard over the buzzing coming from the high voltage power lines. The technicians are bracing themselves for a difficult night. Hani wants to make sure the message gets through before leaving the premises: “We are accused of all evils, but no one is rushing to take the helm.”

According to Kamal Hayek, “There are 1,400 employees at EDL today.” Adequate reforms and “a total number of 5,000 employees” will be needed in order for EDL to be fully responsible for running the grid, he says.

This goal is farfetched, particularly as Lebanon sinks deeper into crisis. “Being a civil servant used to be a goal in itself in the past. Today people are driven away from public service,” the engineer says. “Some of us have more than 25 years of service. Who will fill the void when they leave?” he asks.

Before closing the gates and leaving inside these few Lebanese who are in charge of operating what has left of the national power grid, Hani lets it slip. “When at home, my son asks me why there is no electricity,” he says with a rather pained smile. “We are still working because we have professional conscientiousness, but, deep down, we are just like everyone else (…).”

That is when Pierre, the technician, calls to him from the control center’s window. Night has fallen. It’s time to go. Hani looks around at his daily life, as if he really wants to believe that what he just said is real, but finally he spits it out: “Deep down, we just want to get out of here.”

* The interviewees did not want their names to be revealed in this article.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub and Joelle El Khoury.