A cluster of generators on a Beirut street. (Credit: Reuters)

BEIRUT — The question of generator profits has been hotly contested in recent months, with some politicians, journalists and ordinary citizens accusing generator owners of taking advantage of the state’s failure to provide electricity to reap excessive profits.

Generator owners, meanwhile, charge that the political class is demonizing them for political gain ahead of elections and setting tariffs at rates that don’t cover their costs, let alone make profit.

Lebanon’s entire private generator industry is technically illegal but, given the constant shortfalls of state energy utility Electricité du Liban, officials and the public have largely accepted the generators as a necessary evil. In recent years, the state has attempted to regulate the industry.

The most recent attempt was in September, when the government again tried to require generator owners to install meters and charge based on consumption. So far the latest attempt at regulation, like those before it, appears to be falling flat.

In the meantime, amid worsening shortages in state energy supply, those Lebanese who can still afford a generator subscription are facing skyrocketing costs with little effective oversight and control of the sector.

L’Orient Today set out to analyze, to the extent possible with the information available, the pricing structure and profit margins of the generator industry.

Interviews last month with 31 people found that, of the 22 who had subscriptions to neighborhood generators, just four had meters installed on their lines, despite the fact that generator owners have been obliged to install such meters since October 2018. None of the four people with meters lived in Beirut.

Fifteen Beirutis who spoke to L’Orient Today said they had unmetered flat-fee generator subscriptions. The 11 of them who received 5 amperes reported paying between LL550,000 and LL2,000,000 monthly. There was little rhyme or reason in the billing rates. Three residents of the neighborhood of Geitawi, all with 5 ampere flat-fee subscriptions, reported paying LL550,000, LL900,000 and LL1,250,000, respectively.

The situation is unsustainable for many consumers. At the current exchange rate of LL27,000 to the dollar, LL1.25 million lira comes out to $46 per month for an electrical service that is shut off for several hours a day and doesn’t allow the customer to use larger appliances.

Given the opacity of the generator sector in Lebanon, L’Orient Today has calculated the bills customers would pay under different conditions to see what factors might lead to generator owners collecting profits higher than the ministry price table provides, and which situations might lead to generator owners making less. The results suggest that meters do not always work in the customer’s favor, but might often work in their favor depending on how much power they use, which could well be less than the amount priced into their flat rate.

Metering is thought to cut into generator owners’ profits, in part by tying their revenue to the amount of power generated. In order to charge customers more, they must produce more electricity, which costs them money both in fuel and in wear and tear on their machinery. Under a flat-fee system, profits are maximized by generating as little electricity as possible while still holding onto subscribers.

The flat fee also allows generator owners to take advantage of the fact that people likely aren’t using their full capacity 100 percent of the time, whereas those extra profits would be lost under a metering system, where customers only paid for the energy they actually used.

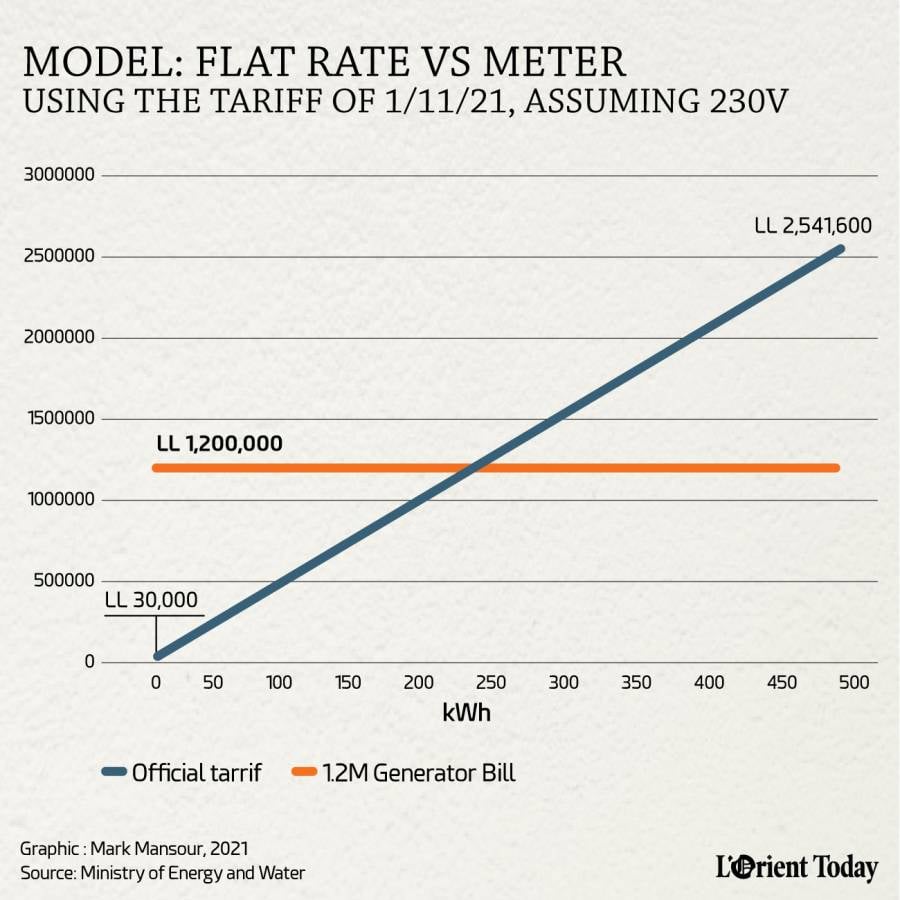

The official prices issued on Nov. 1 were, for city-dwellers, a fixed LL30,000 cost for 5 amps or LL60,000 for 10 amps, plus LL5,200 per kilowatt hour. The generator owners’ syndicate decried the rate as “unfair,” demanding LL5,900 per kilowatt hour, plus a fixed charge of LL50,000 and LL100,000 for 5 amps and 10 amps, respectively.

At the official rate, someone on a 5 amp subscription who used 100 kilowatt hours was supposed to pay LL550,000; someone using 200 kilowatt hours, LL1,070,000; and so on.

For a flat-rate customer who paid LL1,200,000, for example, their bill was equivalent to the official price for using 225 kilowatt hours. If they used less than that, their LL1,200,000 bill would end up being higher than the official tariff they should have paid; if they used more than that amount, their LL1,200,000 bill was less than what the tariff would have had them pay.

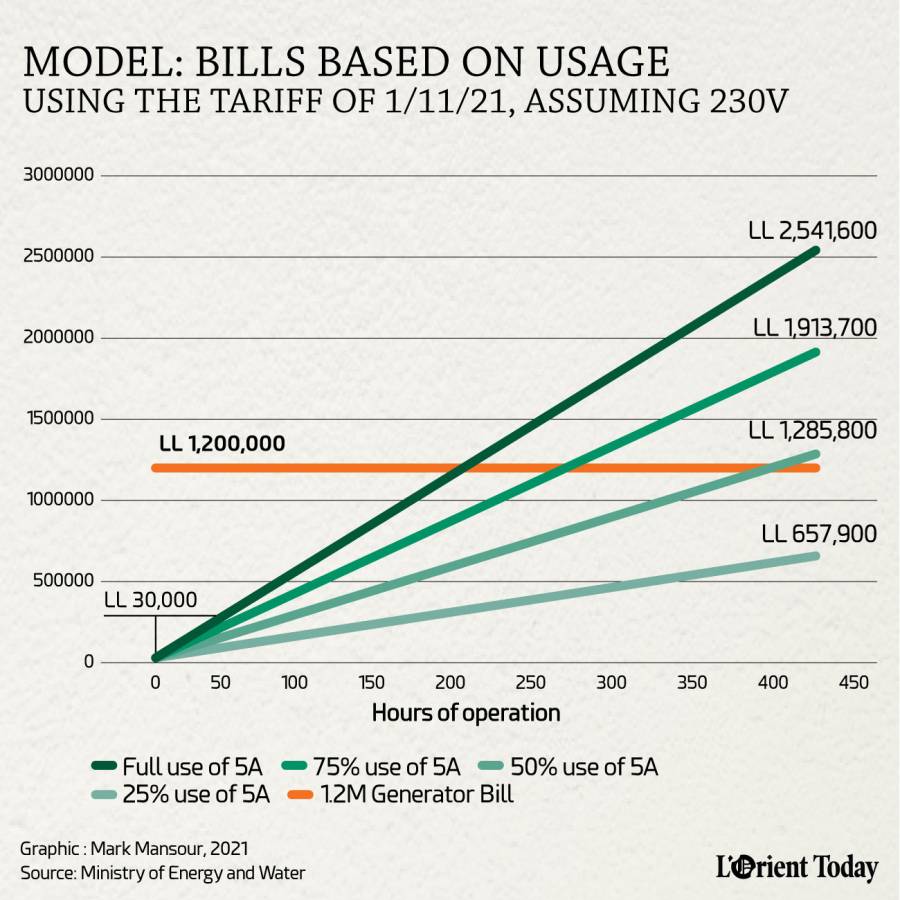

A 5 ampere subscription can deliver 1.15 kilowatts per hour. So a generator subscription that is offered for 14 hours per day can deliver a maximum of 483 kilowatts per month, which the Nov. 1 official tariff priced at LL2.5 million – above what people told L’Orient Today they paid that month as flat-fee users.

That might help explain why, in order to make money, some generator owners might restrict hours of service, place them at awkward times of day, or rely on people using less than the maximum amount of energy possible. For instance, the user might be asleep or at work during some hours of power, not using their 5 amps to the fullest; or, because they cannot easily track their usage at any given moment, they might be using a combination of appliances drawing less than 5 amps without knowing.

The generator owner offering a flat rate of LL1,200,000 can collect profits above the ministry’s price table from all customers who use the full power of their 5 amps for less than 6.5 hours a day, three-quarters of their amperage less than 8.7 hours a day or half their amperage less than 13.0 hours per day. A smart user can benefit from a flat fee, but some generator owners’ resistance to the installation of meters suggests they feel most customers use less than the number of kilowatts allotted by their flat rate.

On Dec. 1 the ministry issued an updated price table, with the per-kilowatt-hour cost rising to LL6,502 for city dwellers.

The Energy Ministry’s periodically updated price tables state that they are based on the average cost of diesel and various other costs involved in providing generator electricity, in addition to “a good profit margin for the owners.” The calculations are based on an October 2010 accounting table, although last month the ministry vowed to conduct a study “in the coming period” to “modernize the equation” to better reflect “fluctuations in the exchange rate and the economic and social situation for citizens, while taking into account demands of private generator owners

A regulated illegal industry

Despite its size, and its central role in the daily lives of millions of residents of Lebanon, the generator market can be opaque. A May 2020 World Bank study by energy economist Ali Ahmad estimated the subscription generator market at $1.1 billion in 2018, compared to a total GDP of $54.96 billion. It was estimated that 1.08 million customers subscribed to the services of generator owners, comprising an estimated 3,000–3,500 individuals.

Commercial generators are illegal under Lebanese law, generating and selling power outside the legal mechanism for independent power producers created by Law 462 of 2002. Since 2011, however, the government has been attempting to regulate the sector and tacitly acknowledging that it can’t simply eliminate generators as long as the state is failing to provide consistent electricity via EDL. Since 2011 the Ministry of Energy and Water has attempted to set generator tariffs to protect consumers from over-billing. Finally, in June 2018, the Ministry of Economy and Trade threw down the gauntlet and required all generator owners to install metering systems by October of that year.

The deadline was accompanied by inspections to be conducted alongside security forces, hundreds of fines, the confiscation of generators and even the arrests of owners. By the following March, the Economy Ministry claimed that 60 percent of subscribers in Lebanon were metered and bills had been reduced by half.

But Beirut was largely sidestepped, partly because it had the country’s best service from EDL. In 2018 the capital averaged 2.8 hours of daily power outages, compared to 11.5 hours in Baalbek-Hermel.

“Back then it was a decision by the Council of Ministers that Beirut should always benefit from 21 hours because it is the center of economic activities, it has a lot of ministries, etc., and not all of those have generators,” said Marc Ayoub, coordinator of the energy policy program at the American University of Beirut.

Achrafieh generator owner Chaamoun Chaamoun recently told local media that one reason for the lack of meters in Beirut is that Beirut’s power outages used to be short enough, and bills allegedly low enough, that many customers were not concerned with metering.

This is generally accurate, Ayoub said. “Back then, the flat fee [for Beirutis] was lower than a subscription per kilowatt hour,” he explained. Many even signed papers waiving their right to have a meter installed, he said, adding, “but now they are paying the price.”

Also, unlike in other areas of the country like Tripoli – where low-income subscribers are able to purchase flat-fee subscriptions for small amounts of power, like 1-3A – Ayoub said in Beirut it is rare to find generator operators offering less than 5A subscriptions, which have become unaffordable for many.

Bassam Hamze, a generator owner in Jard Aley who said he has long used meters, alleged that some unscrupulous owners pressured customers, who indeed wanted meters, into waiving their right to a meter, lest they lose service altogether.

His account was echoed by former Economy Minister Raoul Nehme, who also said some generator owners have in the past told customers they could either accept the flat fee on offer or live without a generator subscription.

With Beirut suffering from EDL cuts most of the day and night, and generator bills being revised upwards seemingly at random, customers are eager to gain control over their utility costs.

In September then caretaker minister Nehme relaunched government efforts to bring meters to the generator market, setting a new six month deadline for holdout owners to come into compliance.

His successor in the position, Amin Salam brought up the deadline via a circular on Oct. 7, requiring generator owners to install meters to measure subscribers’ energy usage, at their expense. He gave them a new deadline of Nov. 11.

Last month, three days before the deadline, Salam toured the capital alongside MP Roula Tabsh (Future/Beirut) to inspect the progress of the installation efforts, where he was reportedly met with angry generator owners who claimed they could not bear the cost of installing meters.

In a statement following the tour, Tabsh stressed the need to bring Beirut into alignment with the other regions of Lebanon, where meters are more common. “We want justice for all,” she said, “and the people of Beirut are envious of the rest … The families of Beirut live in darkness.”

That same day Beirut governor Marwan Abboud added further pressure, announcing the same day that municipal employees would begin inspections within a week to verify the installation of meters and mete out punishment for tardy compliance, including fines and possible confiscation of generators.

Weeks after the latest deadline came and went, many inside and outside Beirut still lack meters, and others report being told by generator owners that they must bear the cost of the meter themselves, in direct contradiction to the law. This despite the fact that the municipality has engaged in some enforcement actions, referring at least six cases to the courts to seize generators in Ras al Nabaa, Al Mazraa, Geitawi, Hamra, Rmeil and Sodeco.

Meanwhile some municipalities, like Sir-Dinniyeh in the North Governorate, are trying to negotiate between the demands of generator owners and consumers, trying to goad generator owners into adhering to a price higher than the official ministry tariff, but below their current prices. “No one” adheres to the ministry price, said mayor Ahmad Alam. He is trying to strike a middle ground, “maybe now [the owner] doesn’t profit at LL8,000, but he doesn’t lose either.”

The Economy Ministry declined to comment on the progress of their enforcement efforts.

Abdo Saade, head of the generator owners’ syndicate, said that 75 percent of generator customers have meters, and “25 percent of people said they do not want meters.” Some of those who initially said they don’t want meters, he said, have changed their minds and are now requesting meters, which generator owners are willing to provide. He disagreed that Beirut has fewer meter customers than other regions. “We followed the decision of the Economy Ministry... There was a group of people who told us they don’t want [meters]. Now they’re saying they want meters, we will give them meters, tikram aynak, and we are for the meters.”

“But give us fair pricing,” he added, “for the 75 percent who have installed [meters] and for those who now want to install meters. Because if you were losing [money] on each kilowatt, could you continue?”

Abdo Saade said generator owners are being unfairly blamed for the failures of the government and are at the mercy of fuel prices set by the Energy Ministry, which has largely phased out fuel subsidies as the central bank’s foreign currency reserves have continued to shrink.

“It’s not our problem if they don’t have money, because they took the money, not us. It was the authorities that took the money, not generator owners … If the price of 20 liters of diesel were LL100,000 or LL150,000, people’s generator bills would reach LL300,000 or LL400,000,” Saade said. Alternatively, he suggested, the state could lower consumers’ generator bills by providing more state electricity.

Electricity from EDL is substantially cheaper than generator electricity but, unlike generator owners who operate generators as a business, state-owned EDL has priced its electricity below cost for years, adding its losses to the state budget deficit. There is now talk that EDL will dramatically increase its tariffs in order to at least cover its costs.

Prior to the economic crisis, Ali Ahmad estimated that a single 500 KVA generator, following the official government tariff, brought its owner around $4,200 in profit per month. With the price of fuel rising, it seems as though the profits are no longer what they once were.

More recently, Al Jadeed television presenter Joe Maalouf presented what he said were the accounts of a generator operator running a 160 KVA generator. According to this operator’s accounting, the generator brought in LL40 million per month, the equivalent of about $1,800 at the parallel market rate at the time of the broadcast. This profit was earned, Maalouf said, while charging LL5,000 per kWh.

As a general approximation, Ahmad says the cost of generator energy production is roughly equivalent to the cost of fuel plus 10 percent for operations and maintenance. On Dec. 1 the government claimed that last month’s average price for 20 liters of diesel was LL314,386, which would make the cost of energy production using a typical 500 KVA generator LL5,404 per kWh. If generator owners operated on the official tariff of LL6,502 per kWh, that would leave them with a profit of LL1,098 per kWh. What these numbers look like in reality, where many generator owners say they purchase diesel in dollars at much higher prices, is hard to say given the lack of clear data.

For Hamze, the generator owner from Jard Aley, the situation needs government transparency. He says generator owners don’t have access to the formula used by the Energy Ministry to calculate tariffs, despite obtaining a judicial decision that the government had to release its formula.

The Energy Ministry did not respond to questions about these claims.

“Let the energy minister … go to the media and show the price table like we’ve been requesting for more than six months,” he said. “Go to the media, show this table … offer it to everyone all together and inform the people how you are pricing.”

In the meantime, the public is left with recriminations, finger pointing, and high bills.