The Fatmagul Sultan, docked of the coast of Zouk. (Credit: AFP)

This is the first part of a two-part investigation. Read Part II here.

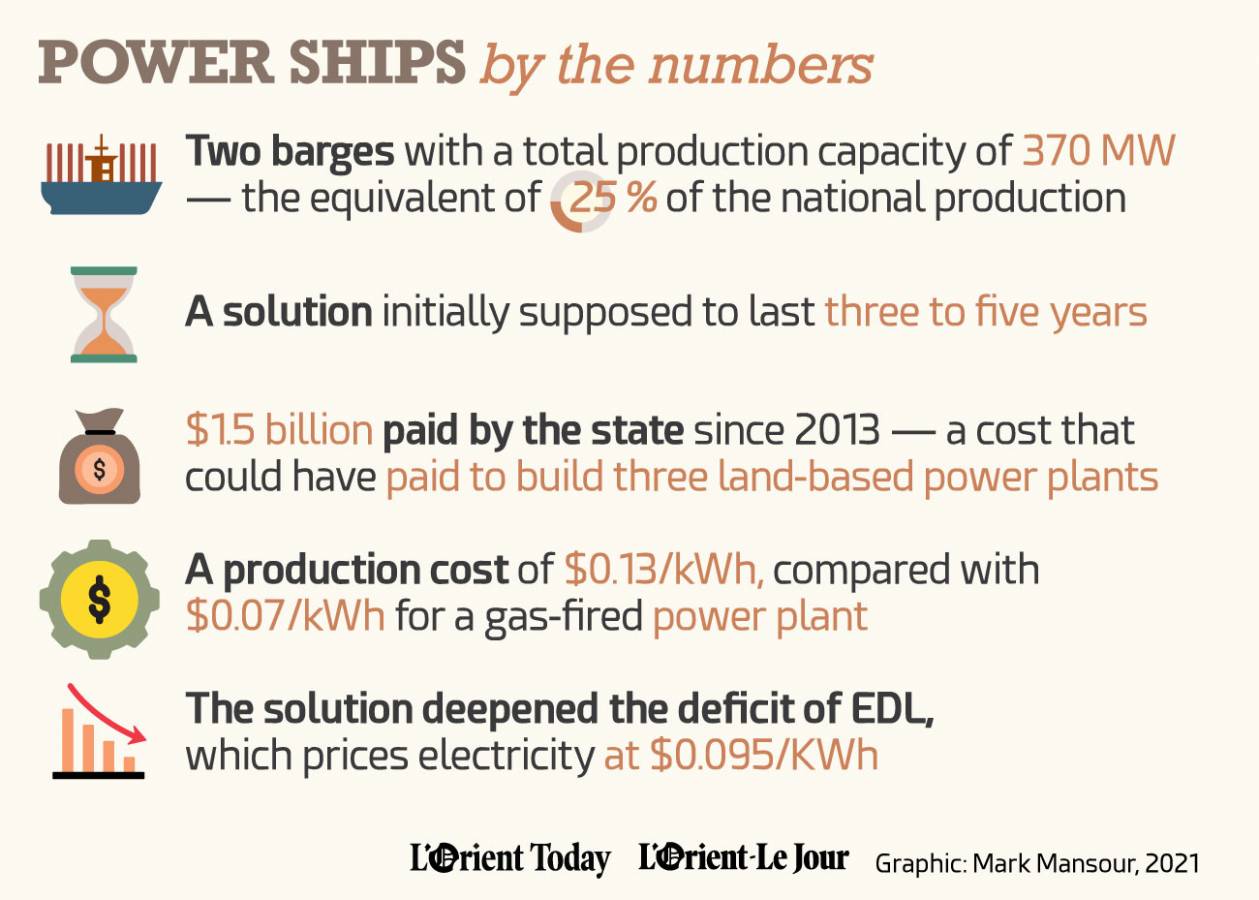

Purchases from power barges have cost Lebanon more than $1.5 billion since the government signed an agreement in 2013 with Karpowership, a subsidiary of the Turkish energy company Karadeniz. This is excluding the cost of fuel supplied by the state to run the barge. For a slightly larger sum of money, Lebanon could have endowed itself with almost three land-based power plants.

The project, which cost the state a fortune, proved quite profitable for the Turkish company. An analysis by L’Orient-Le Jour found that Karpowership has generated $750 million in profit in eight years. At that cost, it would have been cheaper for Lebanon to buy the power barges than to hire them.

Instead of purchasing its own power barges, Lebanon opted for a supposedly interim solution, but then renewed the contract with Karpowership twice — in 2016 and 2018.

Why insist on the vessels, instead of investing in long-lasting and cheaper solutions when the country still had the means to do so?

A judicial probe into corruption and money laundering charges opened in March by an investigating judge in Beirut against some of the company’s officials may reveal some answers.

Aside from the alleged commissions, documents reviewed by L’Orient-Le Jour, including the terms of the contract awarded to Karpowership, raise serious questions about poor negotiating and suspicious tendering.

The first part of this investigation is centered on a procurement process that seems to have been tailored to Karpowership.

In A Nation’s Dream, an illustrated booklet produced in 2013, then–Energy Minister Gebran Bassil imagines taking his son on a tour across Lebanon in 2020, after all his projects are completed. Boarding a train from Batroun to Beirut, father and son are dazzled by the vast public beaches and enjoy purified air in Zouk and Jiyyeh following the restoration of the power plants there. As they pass by Dora, the landfill is replaced by a tourist attraction.

“I am proud to be one of those who turned Lebanon into a stable and prosperous country,” the minister tells his son.

Eight years later, the country is in agony. Ironically, the near-total blackout has become a fait accompli amid a liquidity crunch, fuel shortages and arrears in state payments to the various operators in the sector.

It is clear to any observer that almost no action has been taken to ensure sustainable energy-saving solutions over the past decade.

The two barges from Turkey’s Karpowership are in many ways a symbol of the sector’s malfunctions, which include opacity in public procurement and a lack of planning.

The documents reviewed by L’Orient-Le Jour — namely, calls for tenders, the contract and notes from Electricité du Liban and the Central Inspection Board — reveal that red flags have been present from the beginning. These lead to serious suspicions of favoritism in the awarding of the contract to Karpowership.

Let’s go back in time. Bassil has used the electricity sector’s reform as a key hobbyhorse since 2010. Ambitious as an energy minister, he knew well that succeeding in this sector could rapidly propel him to the top. And he was in a hurry.

The cabinet voted on his reform plan on June 21, 2010. His road map aimed to drive up the country’s production capacity to 4,000 megawatts by 2014, up from the 1,500 MW capacity at the time, so as to ensure around-the-clock electricity supply across the country.

The barges were first raised as an option at that moment. Bassil’s ultimate plan involved building a new power plant in Deir Ammar and two new units in Zouk and Jiyyeh, in addition to rehabilitating the old power plants there. The old plants would have to be shut down during the renovation process. Consequently, it was suggested to opt for an interim solution to avoid a sudden drop in capacity.

The power barges allowed EDL to save on land expropriation and leasing expenditures — not an unreasonable solution, had it been only temporary.

“Resorting to power barges could be justified as a short-term use. In the long run, the lease loses its cost-saving [advantage], particularly since no transfer of assets is made at maturity,” says Marc Ayoub, an energy researcher at the American University of Beirut’s Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs.

The die is cast in advance

With the plan approved by the cabinet, Lebanon began to search for an operator, and from 2010 the Turkish company had the state’s approval. “There are not many barges in the world. Given the limited choices, we considered an offer from Turkey in this field, while we keep our options open,” Bassil said at the time.

“The government, which began to receive more and more offers from companies, finally decided to formalize the bidding process,” a tenderer for the contract says.

Two years later, the cabinet formed a committee that was chaired by then–Prime Minister Najib Mikati and consisted of the justice, environment and finance ministers, in addition to the Swiss firm Pöyry, which was later brought on as a technical consultant along with the French law firm Gide Loyrette Nouel.

The committee was tasked with leading the call for tenders, approving the statement of requirements and the standard contract and negotiating with the candidates.

Then came the first red flag. “The ministry’s role is to determine the policy and general vision, not to launch the calls for tenders. This is contrary to good practice. EDL, as an independent entity, should have done that,” says Jessica Obeid, an independent energy consultant.

Article 2 of the Public Tenders Law stipulates that public institutions should take charge of organizing their own procurement contracts. However, a government source says that “the cabinet has jurisdiction,” arguing that EDL’s deficit is financed by public funds, which gives the cabinet the right to scrutinize the institution.

Chaos is common in public procurements, which in Lebanon’s energy sector are often riddled with corruption due to the size of the sector’s financial flows. A unified public procurement law was adopted only recently, on June 30. “The regulatory framework was fragmented to the point that it was impossible to identify the responsibilities of each person,” Obeid adds.

The second irregularity lay in the request for proposals itself, which L’Orient-Le Jour reviewed. The document, which including its annexes is 12 pages long, “is commensurate with a $10,000 project,” Obeid says, not with a project worth $400 million.

The document is light regarding the evaluation criteria that should govern the operator’s selection.

Nearly 60 firms obtained the call for proposals’ document, but only six companies submitted complete offers. The negotiations between the ministerial committee and the tenderers were held across multiple meetings. Most tenderers were excluded gradually following the technical appraisal of their offers, leaving only two final companies: the US firm Waller Marine — Buildum Ventures and Karpowership.

Discussions continued with the two finalists until they submitted their price quotations. But according to a representative of Waller Marine — Buildum Ventures, the die had been cast in advance.

“During the final negotiation phase, the committee asked me to reduce the price, which I consented to on the condition that the last financial offers be sealed at the tender’s opening. But I needed to wait for confirmation from the headquarters in the US. However, the committee didn’t even bother to wait for the latest offer. When Karpowership went in, it was directly selected,” recounts a representative of the candidate, who learned the news while in the Grand Serail’s waiting room.

Karadeniz’s political connections also raise doubts in this regard. Karpowership’s representatives in Lebanon are Samir Doumit, a top Future Movement official who is married to a cousin of Nazek Hariri, the widow of assassinated former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, and Doumit’s nephew Ralph Faysal, who is allegedly a close associate of Bassil’s.

“The alliance between the Free Patriotic Movement and the Future Movement in the dossier was cemented around this duo,” an energy sector source says.

“Nader Hariri, Saad’s cousin, was going to be the kingpin of the dossier. At a later stage, this matter will become part of a broader agreement between Bassil and the Future Movement, [which] will not be limited to the financial side but will also involve a political agreement on the shares in the appointment of senior civil servants,” a political source adds.

For its part, the government reportedly underscored that the offer was selected away from any political considerations, arguing that only the timelines for delivery and the fuel price and consumption levels were taken into account.

However, it is impossible to confirm [the government’s response], because the tendering terms changed during the final negotiations with Karpowership. This is the fourth red flag in the tendering process.

While the Energy Ministry celebrated having directly negotiated a price drop of $0.10 per kilowatt-hour with Karpowership, a tradeoff was swept under the carpet.

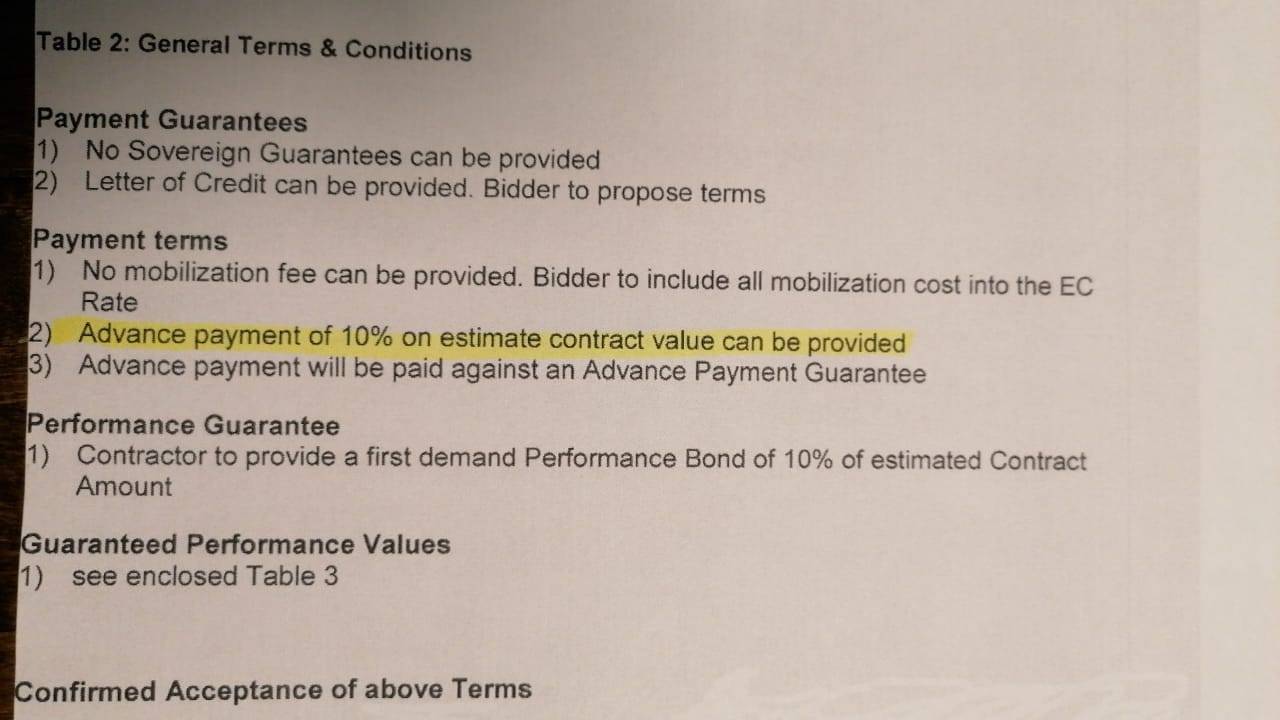

An advance payment made by the state rose from 10 percent, as stated in the tender annexes, to 22 percent under the contract signed with Karpowership (see Figure 1).

“Every modification to the tendering terms needs to be communicated with all participants ahead of time. This is what ensures fairness and transparency in tendering. Perhaps other firms would have offered a better price or additional candidates would have made offers” in accordance with the new terms, Obeid says.

![]() Figure 1: Excerpt from the contract related to the state’s deposit, mentioning the 22 percent advance payment.

Figure 1: Excerpt from the contract related to the state’s deposit, mentioning the 22 percent advance payment.

Commenting on the matter, Karpowership tells a different story. “The call for tender was open to all the world’s power generation companies, and Karpowership made the lowest price bid. It is not uncommon to hold direct negotiations with the bid winner, particularly since Karpowership has introduced a new technology in Lebanon,” the company says.

Furthermore, Karpowership denies that the advance payment percentage was communicated with all bidders ahead of the agreement. “The request for proposal [distributed to candidates] did not specify an advance payment percentage. This was agreed on during the contract negotiation phase.”

Such a statement, however, is contradicted by the clarifications provided to the candidates, of which L’Orient-Le Jour secured a copy. They stipulate that the Lebanese state can provide an advance payment of up to 10 percent on contract value (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mention of the 10 percent advance payment from the Lebanese state in the request for clarification.

Figure 2: Mention of the 10 percent advance payment from the Lebanese state in the request for clarification.

A lavish bonus

A first ship, the Fatmagul Sultan, docked off the coast of Zouk in 2013. The barge was followed by the Orhan Bey, which docked at the port of Jiyyeh three months later.

Things got tough in the first few weeks. In April 2013, the Fatmagul Sultan broke down. Central Inspection stepped in in a bid to provide insight into the reasons behind the breakdown.

In its report, which L’Orient-Le Jour reviewed, Central Inspection states the breakdown was connected to a fuel problem: the fuel supplied by the British Virgin Islands–based Sonatrach’s offshore subsidiary via its subcontractor BB Energy was off-specification.

“It was a poor-quality fuel supply. While it did not affect the older generations of plants, the new engines could not withstand it,” an energy expert says.

Following the incident, Sonatrach’s subsidiary in the British Virgin Islands — which presently faces charges of corruption in relation to its role as part of a network that allegedly delivered tainted fuel to EDL — began supplying another type of fuel, although no tenders were issued.

It was a Grade B–type fuel — namely, its quality was higher given its lower sulfur level — unlike the Grade A fuel destined for the old power plants in Zouk and Jiyyeh.

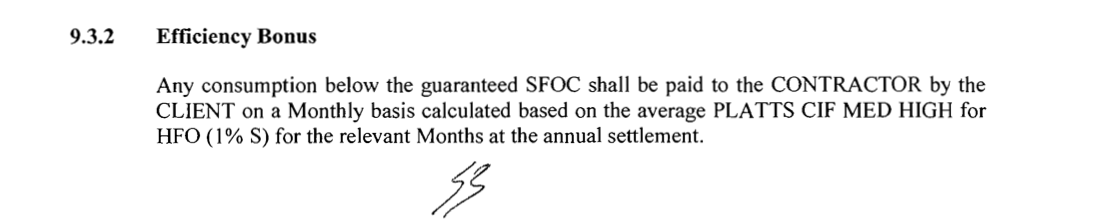

Besides the fuel problem, the inspection report underscores that the contract includes multiple gray areas. The main question mark deals with a bonus-related clause (Figure 3), which Central Inspection advised against.

Figure 3: A contract excerpt showing the bonus clause.

Figure 3: A contract excerpt showing the bonus clause.

The contract provides for paying Karpowership a premium that would be calculated based on the price per barrel of fuel, in case the barges require less fuel than the Lebanese state has committed to supplying.

Such a provision is supposed to encourage the operator to consume less fuel, and sometimes the profits are shared by the operator and client. “It rarely goes entirely to the latter. Our offer did not involve one,” a candidate for the original tender says.

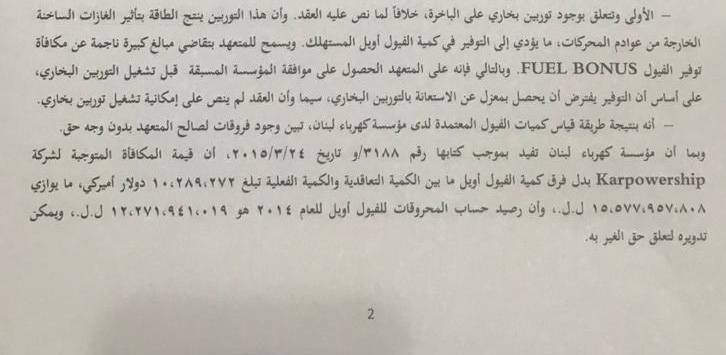

The operator is required to pay a penalty that could have balanced the bonus in case it surpasses the fuel ceiling set out in the contract, but Karpowership made sure that consumption stayed below the limit set out in the contract at all times, as indicated by a document from EDL’s investment department dated 2015, which L’Orient-Le Jour reviewed.

The document also reveals “unrightful variances in favor of the operator” (Figure 4). What was Karpowership’s trick to optimize efficiency? It resorted to a steam turbine, “contrary to the terms of the contract,” and without communicating this to EDL.

Figure 4: Excerpt from the document of EDL's investment department, which states that the bonus clause unduly generated revenues for the operator.

Figure 4: Excerpt from the document of EDL's investment department, which states that the bonus clause unduly generated revenues for the operator.

“Efficiency is the amount of kWh generated, compared to fuel consumption. However, the steam turbine installed on the barge generates electricity through exhaust gases emitted by the main engines, which improves efficiency without consuming more fuel,” an energy expert says.

Hence, the bonus proved very profitable for the Turkish company. The latter received $10 million in bonuses in 2014, according to the EDL document. Since 2016, Karpowership has been required to obtain prior approval to operate the turbine.

Was the ministerial committee kept in the loop that the barges’ fuel consumption was invariably lower than the established ceiling? Was it aware that a steam turbine was being operated? Was the use of the steam turbine about poor negotiations or covert interests? In any case, these pitfalls could have been avoided had the tendering process been competitive.

Karpowership has refrained from commenting on the $10 million bonus, but states, “The steam turbine operation is without any additional benefit or bonus to Karpowership, but EDL will be the one benefitting from it, since it will provide electricity to Lebanon without the need of EDL to supply the fuel to it.”

However, this statement ignores that at least until 2015 the power output of steam turbines was metered similarly to that of regular engines, enabling Karpowership to inevitably get the bonus.

A substantial cost for the Lebanese state

When political obstacles impeded in 2016 the construction of the Deir Ammar 2 power plant, which was supposed to generate the power supply necessary to dispense with the offshore vessels, the contract with the barges was renewed for two years. It was later extended until 2021. This time, EDL’s recommendations were seemingly taken into consideration.

The most recent amendments, which L’Orient-Le Jour reviewed, abolished the fuel bonus and adopted a new list of fees. The price per kWh of electricity generated by the barges dropped from $5.95 cents to $5.85 cents, and to $4.95 cents per kWh in 2018 — the fuel cost excluded. The steam turbine’s output, 20 MW, is now metered differently and unbilled. Subsequently, production rose to 370 MW, compared with the 270 MW stipulated under the initial contract, to amount to nearly a quarter of the national production today.

The contract’s renewal is far from being painless for public finances. The per-kWh cost of the barges’ production, which is around $0.13, is almost double “that of a new gas-fired power plant, [which uses gas oil, which is] cheaper and cleaner than the heavy fuel oil power ships consume,” Ayoub says.

The fully imported fuel makes up 64 percent of EDL’s costs, according to the 2018 World Bank report. It was in Lebanon’s interest to shift to cheaper fuels.

The selling price of electricity that EDL set at $0.095 cents per kWh does not cover the barges’ production cost. The cost of some of the present land-based power plants’ output is even higher, up to $0.21 cents per kWh for some units, which is attributable to EDL’s dilapidated network. In other words, they are less efficient than a new power plant.

It has been a juicy deal for the Turks. In eight years, Karpowership made an average of about $95 million in profits annually, or some $750 million in net profits during the contract’s duration. This profit estimate comes after debt service, operating and maintenance costs of $0.125 cents per kWh, as per the contract, and major repairs.

“As a typical financing for such a project, Karadeniz had to invest between 25 and 30 percent of the barge’s cost, or $100 million–$120 million, and go into debt for the remaining 70 percent. However, it received more than 22 percent in advance payments from the Lebanese state, or $86 million, which reduced its initial investment to between $15 million and $35 million. This enabled the amount originally invested by Karadeniz to grow by 20 to 50 times in eight years. In contrast, similar infrastructure projects allow the investor to increase [initial] investment [twofold] in 10 years in the best-case scenario,” another energy sector source says.

Nevertheless, Lebanon’s economic crisis ended the love affair. For a year and a half, EDL has not paid the operator, falling more than $170 million in arrears.

A May report from Al Jadeed exacerbated the issue. The channel secured recordings revealing that Karadeniz representatives, Ralph Faysal; Fadel Raad, who serves as the intermediary; and Ahmad Safadi, the nephew of former Finance Minister Mohammad Safadi, agreed on sharing an alleged commission of $6 million.

The Lebanese judiciary issued warrants for the former two, who were arrested before being released on bail, and immediately issued a decision to seize the barges. The decision was reneged on a few weeks later.

Karpowership describes these developments as contrary to the “rule of law,” adding that it was “disappointed” and “very alarmed by the unlawful actions and comments to the press by members of Lebanon's judiciary targeting the company’s assets and employees.”

In protest of the judiciary’s actions, the company decided to halt production, removing 370 MW from the grid, equivalent to about four hours of electricity supply per day.

In a recent twist, the company announced on June 29 its decision to resume power supply, describing this as a “goodwill” gesture and “taking in consideration the summer season and Lebanon’s humanitarian needs.”

This article was originally published in French in L’Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.