The Orhan Bay power barge, docked off Jiyyeh, south of Beirut. (Credit: Sébastien Bruvier)

This is the second part of a two-part investigation. Read Part I here.

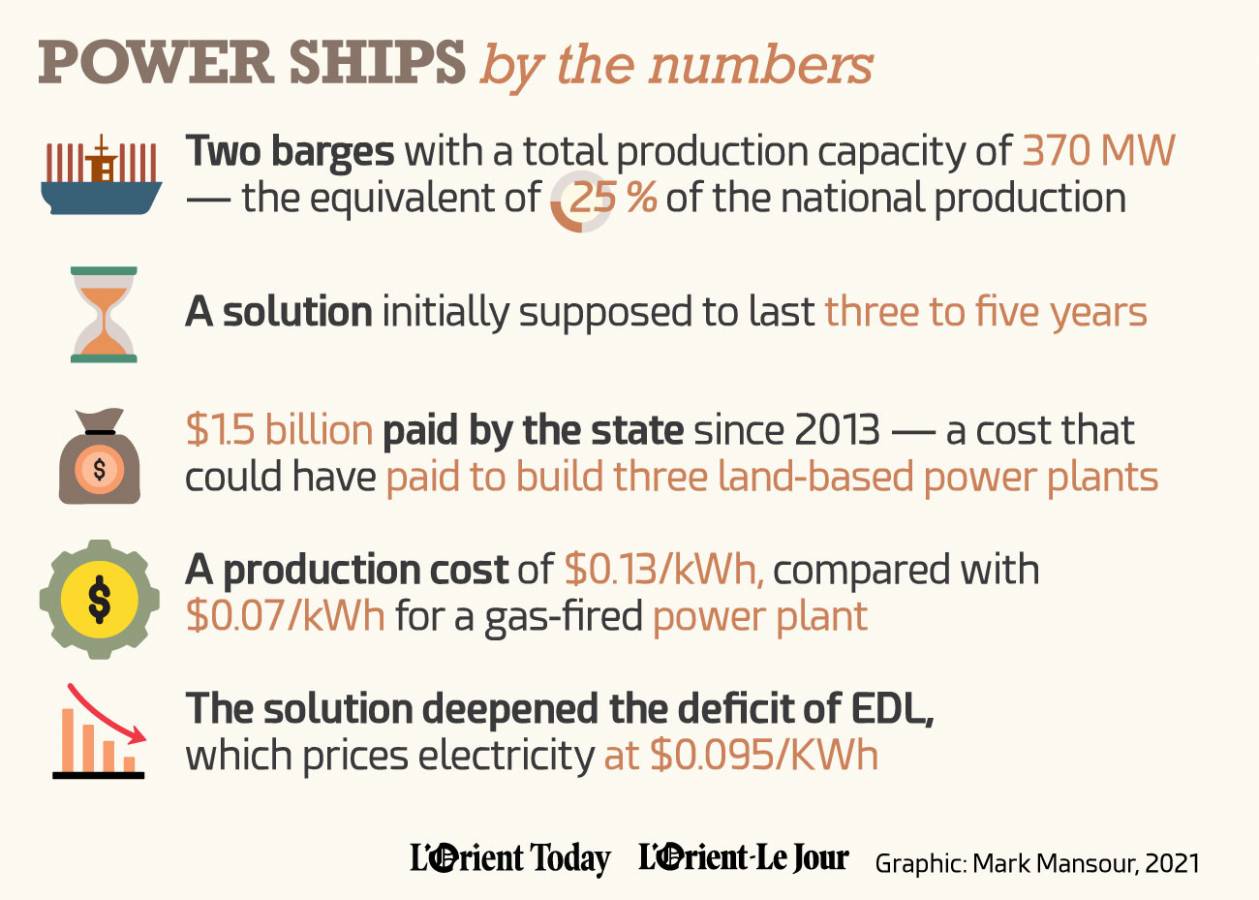

The second part of this investigative report focuses on 2017, when the government tried to triple its investment in electricity produced by power ships by bringing in additional barges.

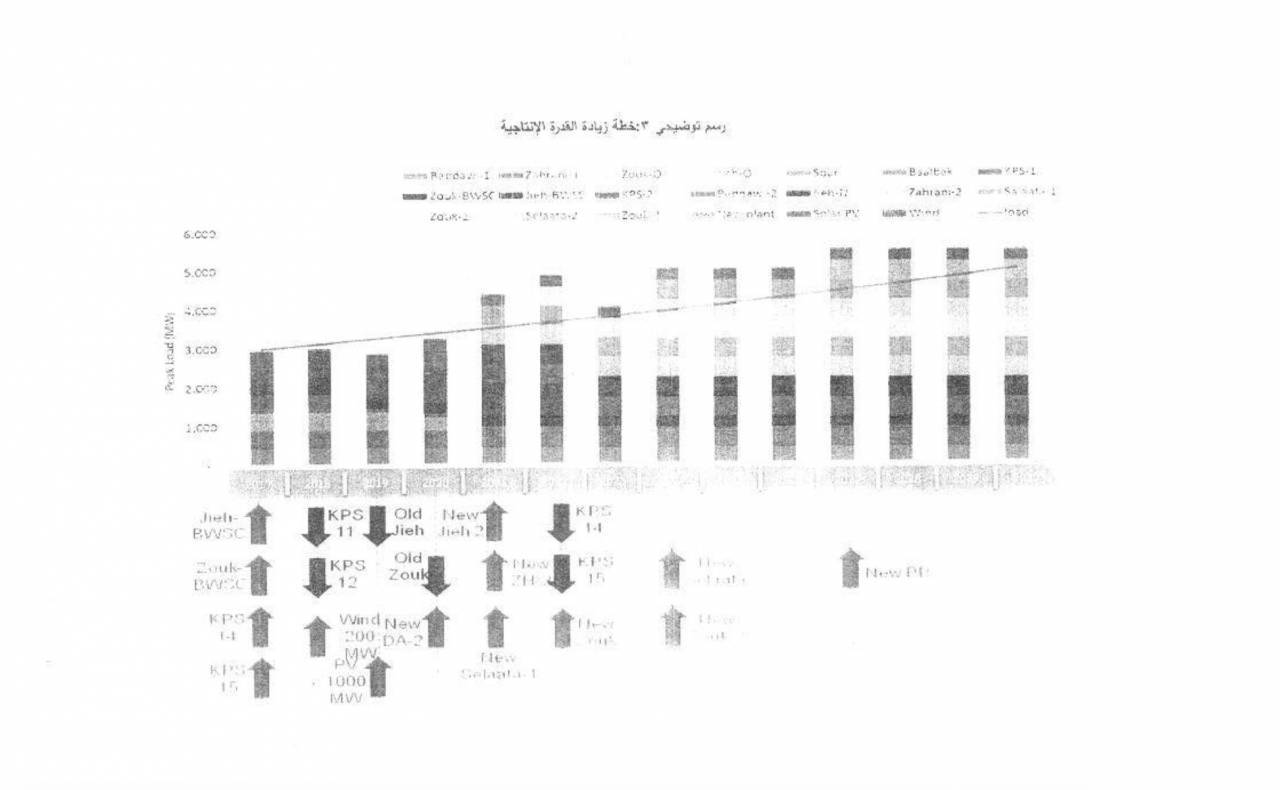

A 2010 plan from Gebran Bassil, the energy minister at the time, had promised to provide the Lebanese with around-the-clock power by 2014.

In 2017, it was hard to find anyone who still believed that he would ever follow through with the promise of 24/7 power, given that the majority of the projects under Bassil’s plan had not been implemented.

What had been done over the course of seven years was limited to the arrival of two power ships in 2013 that provided a total of 370 megawatts of electricity, or about a quarter of total national production today, and the installation of reciprocating diesel engines in Zouk and Jiyyeh, which had a total capacity of 272 MW.

Such a slight improvement in supply did not meet national demand, which had shot up with the influx of Syrian refugees and plummeting production by the old power plants.

In March 2017, then–Energy Minister Cesar Abi Khalil of the Free Patriotic Movement submitted a new plan to the cabinet. In a bid to boost power generation by seven hours a day by the summer, the plan suggested contracting two additional floating power plants, which would be docked off the coast at northern Deir Ammar and southern Zahrani for a duration of five years.

Back in 2013, Karpowership, a subsidiary of the Turkish energy company Karadeniz, had been awarded the contract for the original two barges following a tendering process that lacked transparency (see Part I of the report). The Fatmagul Sultan and the Orhan Bey, which docked off the coast at Zouk and Jiyyeh, respectively, were purportedly meant as a temporary solution while the country awaited the construction of permanent power stations.

But four years later, the government sought to repeat the same strategy — or rather expand it, increasing the electricity provided by barges threefold. The two new barges’ total production capacity was established at nearly 900 MW, compared with the 370 MW produced by the Fatmagul Sultan and the Orhan Bey.

One plan, two versions

Abi Khalil’s “rescue plan of summer 2017” was secretly discussed by members of the cabinet, led by then–Prime Minister Saad Hariri. Shortly afterward, the plan was introduced to the public by Sami Gemayel, the head of the Kataeb Party, to whom the document was leaked.

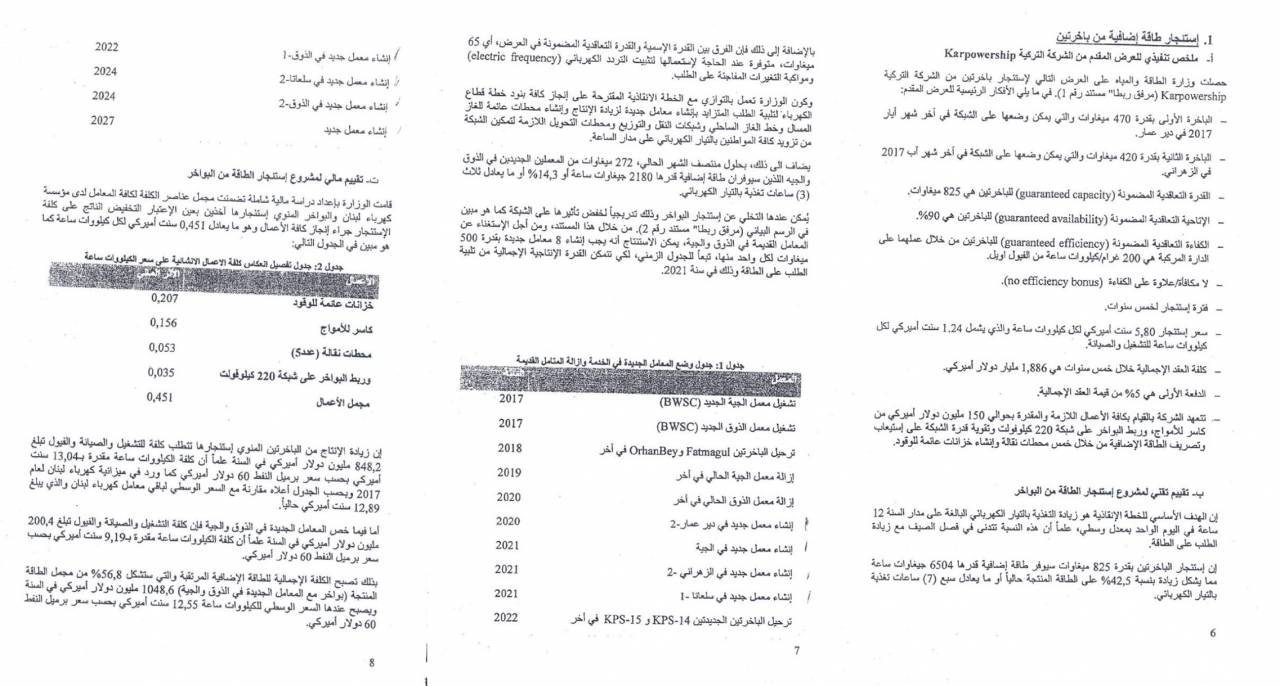

Shockingly, “this first draft, which circulated only among Hariri, Finance Minister Ali Hassan Khalil and Abi Khalil, precisely points to an over-the-counter agreement with Karpowership to bring in two ships [with a capacity] of 470 MW and 420MW. That means the government was planning to dispense with the call for tenders in awarding a $1.886 billion contract,” Gemayel said during a Parliament session (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Excerpt from the version of the electricity plan where an over-the-counter agreement with Karpowership is mentioned.

Figure 1: Excerpt from the version of the electricity plan where an over-the-counter agreement with Karpowership is mentioned.

The government was quick to react. It did not admit the document’s authenticity, and released another version of the plan to the press. The former “was the official draft, which was intended [only] for all ministers. This second version follows the first one almost word for word, except for the part related to the barges. The term ‘Karpowership’ is no longer mentioned, although all the elements referring to the company’s characteristics were retained. But the loophole lies in the annexes, which provide for the arrival of two new barges in 2017, KPS 14 and KPS 15, and these are the initials of Karpowership,” the former MP told L’Orient-Le Jour. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Excerpt from the official draft, with reference to KPS14 and KPS15

Figure 2: Excerpt from the official draft, with reference to KPS14 and KPS15

No official explanation of this point was given. A government source now claims that these codes refer to locations, not ships. However, the source says that opting for an operator that is already working in the country is normal.

A few months earlier, another development had also raised doubts about potential negotiations with Karpowership.

While a delegation of journalists was on a visit in Turkey, a representative from the Turkish company confirmed that consultations were underway with the Lebanese state over the delivery of a third ship, which the government denied immediately.

Karpowership still insists on this version of the story. “Given … that we generate more than 25 percent of the electricity in Lebanon, we made, back then, suggestions to [Électricité du Liban] and the Energy Ministry to increase capacity in Lebanon and lower costs by switching to natural gas, based on global market preferences. But there have never been any negotiations with the Lebanese state on the tender” of 2017.

In a bid to end the controversy, Abi Khalil announced that he would launch a transparent and competitive call for tenders, which ignited the ire of the Tender Board, considering that launching tenders does not fall within the ministry’s purview.

For its part, the government acknowledged that public establishments have the authority to organize their own procurements under Article 2 of the public tendering law, and that EDL should therefore assume this role.

However, because EDL runs a deficit and is unable to finance the project, its administering authority should assume this responsibility. In this case, it is the Energy Ministry. The arm wrestling between these two authorities speaks volumes about the legal ambiguity in the public procurement process. Until recently, Lebanon did not have a unified public procurement law.

The Energy Ministry seemed to have the upper hand. It published a 10-page request for proposal. The document, which L’Orient-Le Jour reviewed, is practically a duplicate of the 2012 file, including the fuel specifications, although they had changed by then.

Nearly 51 companies requested the statement of requirements, and eight made an offer. At the end of the technical selection process carried out with the support of Pöyri, the same international consultant used in 2012, only Karpowership’s offer was deemed compliant with the specifications.

The Tender Board steps in

The news ignited general outcry from civil society and several government actors, including the Lebanese Forces and the Progressive Socialist Party.

“Beware, none of these two parties have their hearts set on public interest or have a desire for reform. Each was keen to defend a model that serves their interests. For some, it is a matter of interests related to [private] generators and the fuel they consume. As for the LF, they defended a model that is similar to that of Électricité de Zahlé,” a politician who declined to be named says.

Faced with this discontent, Abi Khalil ended up submitting the dossier to the cabinet. Unlike in 2012, Hariri decided to loop in the Tender Board, entrusting the latter with opening the financial bids and drafting a report on the tendering process.

“Saad Hariri decided to serve as political arbitrator between the FPM and the LF by including the Tender Board, without suspecting that this step would become a real obstacle,” a source who worked on the file at the time says.

But the Tender Board showed resistance based on technical reasons, and its conclusions were final. According to the board, the tender’s competitive requirements were not met, and it was devised in such a way as to favor the current operator, Karpowership.

The board found several faults, especially a lack of anticipated publicity for a contract of such a big value.

“The tender was announced in neither international newspapers nor the Lebanese official gazette,” explains Jean Ellieh, the Tender Board’s director.

The deadline for submitting bids was another red flag. “The companies did not have more than 15 days before submitting their offers, which is a very short time limit, unless they are already prepared,” he says.

Based on these observations, the Tender Board refused to open financial bids, prompting the government to cancel the process and launch a new call for tenders.

Ping pong

This time, the Tender Board was part of the tendering process, held in 2018, starting from the technical selection phase. The Energy Ministry prepared a new statement of requirements; the document is much thicker — several hundreds of pages.

“It was much more comprehensive than the first version,” one of the candidates says. But the Tender Board was still unconvinced, especially when it came to the timeframe for delivering the barges, set at three to six months.

“It is still too short. The barges are custom-made. That means only the company that already built them is able to deliver them on time,” Ellieh says.

The story of one of the bidders who was on a visit to Turkey seems to confirm this hypothesis.

“We were at the Tuzla shipyard [in Istanbul], discussing with a company a partnership for the barges’ design as part of the Lebanese project. The engineers, who did not know that we were bidding for Lebanon, showed us around where various barges were moored. The engineers showed us two barges for Karpowership, which they introduced as destined for Lebanon — the first [with a capacity] of 470 MW and the other of 420 MW, which met the requirements. One of them even carried the Lebanese flag,” he recounts.

Karpowership maintains that there was nothing unusual. “Our power ships are suitable for a wide range of supply requirements. As per our business model, our fleet of power ships are designed and built ready to deploy on short notice and are not made to order for projects. By continuously constructing vessels in our own shipyard, we offer partner countries a ‘plug a play’ solution that allows us to offer our power ship anywhere in the world with record delivery time as we have a steady output of power ships available,” the company explains.

However, the Tender Board refused to approve the statement of requirements in light of the suspicions. “According to the [public tendering] law, in case the award of contracts fails twice, an [over-the-counter] agreement could be concluded, provided that [this measure] is due to a lack of offers, not to the statement of requirements. However, the Tender Board refused to give in on this point: the statement of requirements did not ensure the minimum level of competition,” Ellieh says.

The dossier went back and forth several times, before the Energy Ministry finally gave up.

For its part, Karpowership denied any favoritism. “The call for tenders was open to all companies the first and second time. The statement of requirements was transparent and open to companies and the public. ... Since our technical and financial offer was not open, we can’t tell if our proposal met the specifications or not.”

The FPM blamed the failed tender on lobbyists of diesel, which is used to operate generators, who it said would benefit from having to provide a greater electricity supply due to the project’s failure.

“Only a forensic audit for EDL and all public institutions and administrations will be able to determine the damage caused and establish responsibilities,” Ellieh adds.

The final attempt

The saga does not end here. The barges resurfaced as part of a 2019 plan by then–Energy Minister Nada Boustani that was adopted by the cabinet, which provided for launching calls for tenders for temporary and sustainable solutions in order to rapidly step up electricity production — the only way to justify charging customers more for electricity as was necessary to reduce EDL’s deficit, according to the prevailing logic.

Several options were on the table for the temporary solution, including building small gas power plants within three to six months, as suggested by General Electric and Siemens in various parts of Lebanon. The other solution was to resort to power ships. Back then, the press raised suspicions that there were negotiations with Karpowership to bring in two new barges. Boustani hastened to deny the rumors to L’Orient-Le Jour.

During the CEDRE conference, held in April 2018 in Paris, the international community pledged to pay more than $11 billion for Lebanon, provided that the country achieves reforms. Yet, the lack of transparency in the award of public contracts worsened following the conference.

CEDRE donors decided to withhold $500 million from the World Bank to the Energy Ministry under French diplomatic pressure. The decision was made following delays in creating a regulatory entity that would be tasked with granting licenses to the private sector to generate power.

“However, the decision’s roots go even deeper. At that time, the international community’s tolerance for the lack of transparency in awarding public contacts in Lebanon’s energy sector was exhausted,” a source familiar with the file says.

A few months later, Boustani’s plan was overshadowed by the start of the economic crisis and the resignation of Hariri’s third cabinet in October 2019, when the Lebanese public took to the streets to denounce corruption among the political class and other grievances.

Her successor, Raymond Ghajar, offered an updated version of the plan, which never kicked off. Today, in a bankrupt country mired in what may be one of the worst economic crises in modern history, all projects have stalled.

The minister explained to the press that his plan was not funded due to Lebanon’s decision to default on a loan from the International Monetary Fund in March 2020, and international donors and institutions have affirmed on several occasions that they are not ready to reach into their pockets unless key reforms are made.

Almost two years since the crisis began, Lebanon seems to be drifting further away from any prospects.

This article was originally published in French in L’Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.

In...