The National Social Security Fund offices in Lebanon. (Credit: Ibrahim Tawil)

This article is part one of a two-part series on pension reform in Lebanon’s National Social Security Fund. Read part two here.

BEIRUT — Parliament’s joint committees convened last Wednesday to study a long-delayed draft law reforming a key pillar of the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), Lebanon’s pension and health-care scheme for private sector workers in the formal economy and their families, potentially bringing Lebanon closer to much-needed social security reforms.

The reform aims primarily at replacing the NSSF’s end-of-service indemnity (EOSI), a one-time cash payment that private sector workers collect at retirement, with a recurring monthly pension, which is the system used in most countries. As an institution, the NSSF also is responsible for health insurance and family allowances for qualified enrollees.

The NSSF is the largest social protection system in the country. It benefited 840,000 people in 2017 and had 57,000 employers contributing, according to a report by Lebanon Opportunities.

Wednesday’s session was the fourth time this year that the draft law, first proposed in 2004, appeared on the joint committee’s agenda. After the meeting, Deputy Speaker Elias Bou Saab (Free Patriotic Movement/Mount Lebanon II) praised the latest version of the draft law and called its passage “imperative” considering the economic and financial crisis facing the country.

But, “there are questions about how we will implement it in the context of the collapse,” Bou Saab cautioned.

MPs will have until next Wednesday to submit written responses to the draft, after which the Joint Committees will reconvene with an eye towards approving the text.

NSSF Director Mohamad Karaki, speaking to L’Orient Today before the committee session, voiced his hope that the law will soon be approved by the joint committees and passed by Parliament.

“For sure it still requires some study in the committees and in the public authorities before it gets passed but it’s about time for it to be passed,” he said.

Why so slow?

When the NSSF was established in 1963, the EOSI was intended to be temporary, and would be replaced by a monthly pension system once the fund got its financial footing.

But for decades that temporary solution has remained in place.

“It has been, for a very long time, refused by many different stakeholders,” said Miriam Younes, project manager at The Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action.

One reason, according to Sami Zoughaib, economist at The Policy Initiative, is that the EOSI payments are cheaper for the NSSF than a monthly pension would be. “It then maintains … the ability of the EOSI fund to continue to fund ill-designed state expenditure,” he said.

Assets of the EOSI fund, which are largely drawn from contributions of private sector employers, have been used to cover shortfalls in the other two branches of the NSSF, and to make up for inadequate state contributions to the Health and Maternity branch. The assets are also heavily invested in state debt instruments, allowing the state to continue spending beyond its revenues.

The NSSF is theoretically independent, and like social security regimes in other countries is supposed to invest its assets to generate returns for subscribers, but, according to a 2022 report by investigative journalism website The Public Source, there has been political resistance on the NSSF’s board to diversifying its investment portfolio.

“We can see that after the Civil War, at least, the independence of the NSSF has been very systematically undermined,” Younes said.

In 2002, then-Prime Minister Rafik Hariri established a special committee to draft a law transforming the EOSI into a pension scheme, which finished its work in 2004, according to a 2023 report by Younes.

The proposal failed to gain any traction at that time, and a new special committee was formed in 2008 headed by then-former chief economic advisor to Najib Mikati Nicholas Nahas in order to keep working on the draft.

The proposal stagnated for two more years, according to Younes’s report, until the Labor Ministry launched a new round of parliamentary committee reviews in 2010, again to no avail.

A special committee continued to meet periodically between 2017 and 2020 to study the law, without the draft making it to Parliament’s general assembly. But there has apparently been an intensification of work on the draft law over the last couple of years.

International Labor Organization (ILO) social security specialist Luca Pellerano told L’Orient Today that the Nahas parliamentary subcommittee of the Joint Committees made “important enhancements” during the last Parliament’s tenure, from 2018 to 2022, during which time Nahas was an MP for North II representing the Azm Movement, including on governance reforms and changes to the way funds are generated.

“For sure the delay was in our favor,” said NSSF director Karaki, because “we changed the philosophy of the project. Before, it was considered like a bank account and what you put in, you get out.” Any financial risks of investments made by the NSSF gone sour, including troubled banks being unable to repay deposits, to date have been on the wage earner.

The new philosophy, he said, is one in which risks are distributed and minimum pension levels are guaranteed, with workers accumulating larger pensions throughout their working lives. According to the draft law, the state will be the ultimate guarantor of the pension scheme’s financing and will make budget transfers to it when needed.

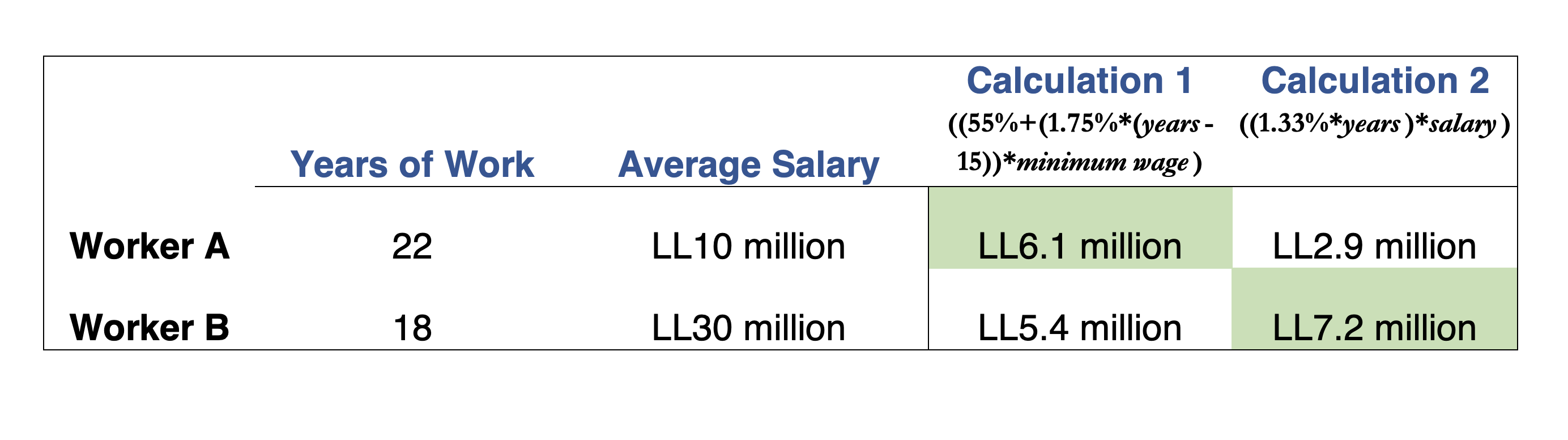

There are two calculation methodologies presented in the recent version of the draft law seen by L’Orient Today, and the pensioner will benefit from whichever results in a larger pension.

One calculation is 55 percent of the official minimum wage that was effective on the date of retirement, with an additional 1.75 percent for each year in excess of 15 years, up to a limit of 80 percent of the minimum wage. This will primarily benefit low wage workers. The second calculation is 1.33 percent of the pensioner’s average salary throughout their working life, multiplied by the number of years of service up to a maximum of 30 years. So a person who works 30 years would receive 40 percent of their average salary.

Under the draft law pension values will be indexed to inflation through a yearly adjustment process.

Karaki says that in the last year and a half the Nahas subcommittee has been making significant progress on actuarial studies, administrative restructuring proposals and asset investment strategies, with technical assistance from the International Labour Organization (ILO).

“This work, we consider an important accomplishment and hope that this time will be the final time to present it to the joint committees, they will agree on it, and present it to the general assembly, which will pass it,” he said.

Nahas told L’Orient Today he considers that the joint committees are approaching approval of the draft law but its path through the general assembly with the presidential election still pending is unclear. Parliament is “not meeting in a regular way, so for that I have no answer,” he said.

In the absence of parliamentary approval of the law, or even in the period between the law’s potential passage and its coming into effect, a transitional solution giving existing NSSF subscribers the choice to receive a pension in line with the conditions set in the draft law instead of the EOSI, could be implemented by decree using language in the original 1963 social security law, according to Pellerano.

Urgency for Reform

In January, MPs on the joint committees requested a financial accounting of the NSSF’s position before moving forward with their study of the law. In February, the International Labour Organization (ILO) produced a financial assessment of the NSSF’s position as of the end of 2020—no small task considering the last audited financial statements from the Fund date back to 2010.

Speaking to L’Orient Today following the committee session, Pellerano said “there is momentum within parliament to advance with this project.” He said the consequences for not reforming the NSSF, are severe.

“Once the situation is as bad as it is right now, it can actually be a chance for change,” echoed Younes.

“The crisis is at a quite critical stage, and poverty is increasing, especially among older people with end of service indemnities, if any, having practically no value. I do see, however, some hope for change since there is more awareness about the impact of the crisis and the current system on the elderly.”

“The ILO’s financial assessment of the NSSF is a milestone as it is the first time we have numbers about the fund,” she added.

Reform of the system will need to answer difficult questions about financing it in a way that provides quality social protection to citizens amid tight budgets and a depressed economy. But many observers seem convinced the answers are at hand.