A man walks past the Banque du Liban (BDL) headquarters in Beirut. (Credit: João Sousa/L'Orient Today)

This article is the second in a two-part series on pension reform in Lebanon’s National Social Security Fund. Read part one here.

BEIRUT — In January, MPs on Parliament’s joint committees requested a financial accounting of the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) before moving forward with their study of a long-stalled draft law to convert the End of Service Indemnity (EOSI) into a monthly pension, the system used in most countries.

A month later, the International Labour Organization (ILO) completed the assessment, using data up until the end of 2020.

Miriam Younes, project manager at The Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action in Beirut and author of a 2023 report on NSSF reform, hailed the assessment as a “milestone” and “the first time we have numbers about the fund.”

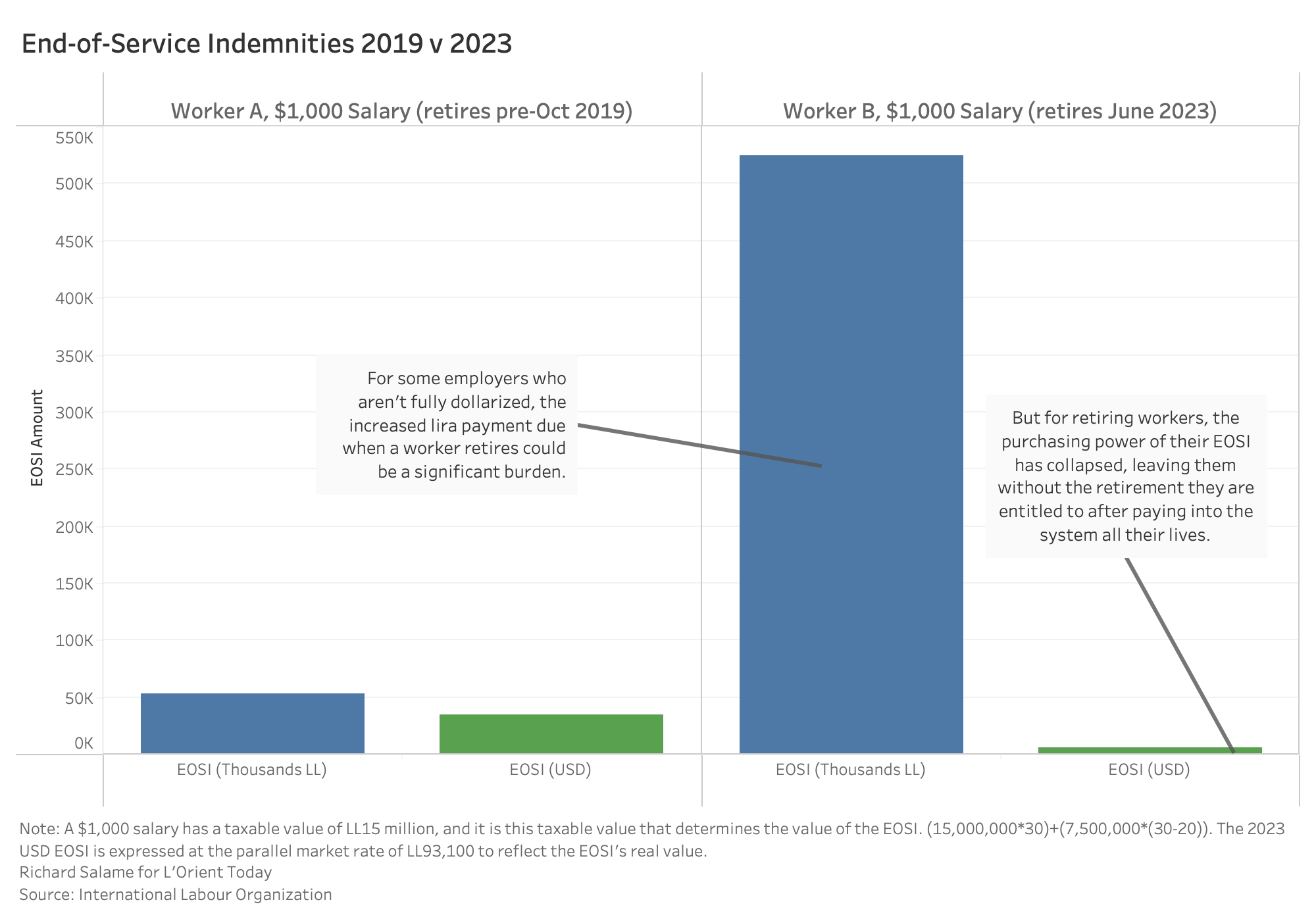

L’Orient Today breaks down some of the ILO findings and shows how the NSSF’s EOSIs are next to worthless for people retiring, though they can be costly for the last employer.

Contrary to some expectations, the NSSF had a net positive financial position as of the end of 2020, because, given the massive depreciation of the lira since 2019, the fund’s payouts are radically reduced, ILO social security specialist Luca Pellerano said.

This positive financial position is not the full story, though. Insured workers’ pensions are worth a fraction of what they once were, and it is the small payouts that keep the balance sheet of the NSSF positive, contrary to the purpose of the Fund, which is to provide social protection in old age.

For instance, pre-October 2019, a 60+ year-old worker (let’s call her Worker A) with an LL1.5 million ($1,000) monthly salary who retires after 30 years of NSSF enrollment could have expected an EOSI of around LL53 million ($35,000). That is, her last salary multiplied by her years of service (LL1,507,500*30) plus half her salary multiplied by her years of service minus 20 ((LL753,750*(30-20)).

A similar worker (let’s call him Worker B) — over the age of 60 with 30 years of NSSF enrollment and a salary of $1,000 — who retires today would get far less.

The following scenario is an optimistic one as most estimates say that, in dollar terms, workers’ salaries are lower than before the crisis.

For tax purposes, Worker B’s $1,000 salary is declared at LL15 million. His EOSI would therefore be LL525 million, which the tax authorities consider the same $35,000 that his colleague received in October 2019. It has a real value, however, of just $5,639, less than a fifth of what he would have gotten four years ago and far from enough to fund a dignified retirement.

Of course, if Worker B’s salary was considered larger in lira terms — for instance, if it was declared at the parallel market rate — the EOSI payment would also be higher. But that would only exacerbate the employer-side problem facing the Fund’s financial future.

Costs on the last employer

Under Lebanon’s scheme, the last employer of the retiring worker is on the hook for the difference between the amount that the worker is entitled to and the amount contributed via NSSF taxes.

If Worker B’s pre-crisis employer was making the required 8.5 percent contribution to the NSSF EOSI scheme, it was paying LL127,500 per month pre-crisis.

These payments made over 30 years accumulated compound interest, and depending on how his salary was adjusted upwards amid the crisis, the total value of the contributions is somewhere between LL99 million and LL148 million, according to ILO calculations shared with L’Orient Today. (We are presenting a range because this exact scenario is outside of the ILO’s model, which did not presume a worker’s salary remained constant at $1,000 during the crisis.)

Because Worker B’s salary was adjusted upwards radically (in lira terms) at the end of his career, his lira EOSI benefit has also ballooned. This leaves his last employer on the hook for between LL377 million and LL426 million or so needed to give him a paltry indemnity of LL525 million ($5,639) on which to live out the duration of his retirement.

This is, in lira terms, far more than the company had expected to pay out when one of its employees retires. Some companies may be able to stomach it, but there are fears that others could be pushed into bankruptcy, further eroding the revenue base for the fund. The large settlement payments could also discourage employers from declaring the full value of salaries to the NSSF, reducing future fund revenue and promoting informal working arrangements, Pellerano said.

The ILO estimates that as a result of the minimum wage increase to LL9 million, EOSI liabilities have increased 70 times, to LL105 trillion ($1.1 billion according to the parallel market exchange rate), the majority of which falls on employers. “It is unrealistic that employers will have the capacity to fully refinance the EOSI system,” they argue.

Solidarity to refinance the NSSF

Providing adequate social protection to retirees and keeping the pension system from collapsing, they say, requires urgent reforms to its structure — namely the shift to a monthly pension scheme that is financed on a principle of intergenerational solidarity.

“The only way to refinance the pension system is through solidarity: solidarity between current workers and pensioners, and solidarity across generations,” Pellerano said. “And in order to establish that principle of solidarity and collective financing, a new pension system is required. It's basically to say the individual savings of workers in the NSSF are not the solution to recapitalize the system.”

He went on: “The settlement payments from employers cannot be the way to recapitalize the system. The only way to recapitalize the system is to establish a new pension system with contributions flowing into effectively a new fund, which will combine the principle of capital accumulation and redistribution to manage the transition across generations.”

Pellerano stressed that the pension system’s biggest problem remains its ability to bring in money from workers and businesses, many of whom underreport salaries in order to avoid paying NSSF dues.

This problem could well become even worse in the future, the ILO argues, as benefits become seen as next to worthless and settlement payments explode. Without the promise of a valuable benefit from the NSSF, workers and businesses will have little incentive to pay into it at the full amount they ought to.

To make matters worse, the NSSF is unable to monitor the accuracy of salary data provided to it due to understaffing and a lack of information sharing with the Finance Ministry, according to Younes’s report.

What are the NSSF’s assets?

The ILO accounting exercise found that the largest asset class held by the NSSF at the end of 2020 was bank deposits, making up over a third of its asset mix. These bank deposits are spread across Banque du Liban (BDL) and 26 commercial banks, with 99 percent of the funds being deposited with commercial banks. Of the total deposits, nine percent, or $367 million, were in US dollars as opposed to lira.

This exposes the NSSF to risks stemming from the banking sector’s bankruptcy, although a 2020 law has theoretically exempted NSSF accounts from some of the informal capital controls facing other depositors. It is unclear whether the NSSF in practice is able to benefit from uninterrupted banking services under this law.

If banking sector restructuring happens, “it will be critical in any kind of bank restructuring or other measures that those NSSF deposits are not considered as large deposits, but as a collection of small deposits and in that sense, receive a special treatment,” Pellerano said.

The NSSF has since 2020 moved its asset portfolio to include more treasury bonds, which now make up roughly 80 percent of its asset composition, Pellerano said.

The NSSF is also owed LL3.37 trillion ($36.2 million at the current parallel market rate) from the central government, an amount which makes up 18 percent of its assets, according to the ILO accounting.

A 2022 report in The Public Source detailed the government’s repeated failure to pay its obligations to the NSSF, which former Labor Minister Charbel Nahas suggested to the reporters was a way to “dominate” the institution.

“This is not a negligible amount, but it’s also not the determining factor that will establish the sustainability of the NSSF in the medium term,” Pellerano said. “The sustainability of NSSF will much more fundamentally derive from the extent to which [it] can recover its ability to receive contributions on the real salaries, from the economy, as wages gradually catch up to the new price situation.”