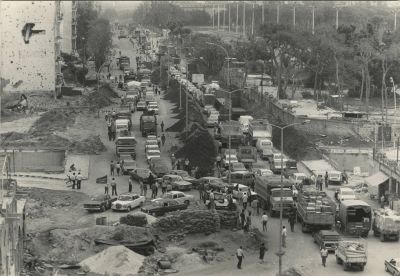

Georges Haddad Street in late Oct. 2022. (Credit: Camille Ammoun/L'Orient-Le Jour)

Who is Georges Haddad, whose name was given to a street in downtown Beirut and who is now at the head of a wide avenue, a section of urban highway? Could Georges Haddad be one of us?

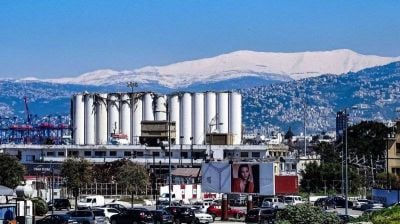

After a quick search on the internet, and after consulting a few people around me, I don’t find anything about him. And yet, a wide but short stretch of asphalt bears his name, and connects the port of Beirut to the more famous Fouad Chehab Avenue: The Ring.

However, this proposed ring road surrounding Beirut was never realized — except in the portion that crosses the city from east to west, now reduced to a vast crossroads. The toponym “Ring” today refers to an area of a few hundred square meters, a point on a map that remains in the imagination of Beirutis their own Checkpoint Charlie. It is a symbol and scar of the physical and political division of their city, their country and their society.

But let us return to Georges Haddad.

If I can’t find anything about the man whose name lends itself to an essential axis of the capital, it is because before the destruction of downtown Beirut by its reconstruction enterprise, Georges Haddad Street was only one of many thoroughfares weaving the urban fabric of the capital.

Similarly, there is the narrow Youssef Hani Street, which sits parallel to Georges Hadded to the east, and the Said Akl Street on its west side. Both Youssef Hani and Said Akl streets could have shared their fate with Georges Haddad.

But real estate capitalism and financial urbanism decided otherwise. And so the modest old Georges Haddad Street was transformed by Solidere into a wide avenue.

Solidere, we tend to forget, is the acronym of “The Lebanese Company for the Development and Reconstruction of Beirut Central District,” a misnamed real estate company since it has probably demolished more buildings than it has built.

Downtown Beirut was destroyed by the Lebanese Civil War but not razed. It was then obliterated in the 1990s, after the end of the military conflict, by the same reconstruction company that also enlarged our little Georges Haddad Street. From the narrow street, they made an avenue to separate the real built environment from the fake, the authentic from the imitation, the old from the new. It separated Beirut from Solidere which had to be glitzy so that investors would pay.

During the popular demonstrations of Oct. 2019’s thawra movement, I remember reading graffiti on the wall of one of the streets leading to the Martyrs' Square: THE NAME OF THIS PLACE IS AL-BALAD NOT SOLIDERE. But one must admit that today the balad, or downtown center, of Beirut is everywhere except in its geographical center. Solidere, by razing it, has transformed this area into a periphery, into an empty center. Perhaps it could have rehabilitated a city ravaged by 15 years of war, but instead it finally undid everything that made it a city by arbitrarily obliterating entire neighborhoods, museifying a hypercenter where an entrenched, illegitimate and iniquitous power is now walled in.

We started this walk under the midday sun between the two garbage dumps of Jdeideh and Burj Hammoud, then we crossed the Daoura roundabout and entered a colorful neighborhood of workers, many of whom are women from Ethiopia, Sri Lanka and the Philippines. In this first section of the street, one can hear Amharic, Sinhalese and Tagalog, but here the lingua franca is a kind of Creole Arabic in the making, dotted with linguistic pearls. These women are among the thousands of migrant domestic workers whose contracts are excluded from the Lebanese labor law and who live under the slavery regime of kafala, or “work sponsorship,” behind the closed doors of their employers’ households.

A few meters further, it is gradually Armenian that mixes with Arabic, and even some Turkish for those who venture to the oldest artisans of Arax Street. After the humpbacked bridge over the Beirut River, French and English gradually replace Armenian, intermixing with Arabic in the cafes and bars of the gentrified Mar Mikhael and Gemmeyzeh neighborhoods.

And here we are, continuing our walk, crossing Georges Haddad Street, which was once walkably narrow, and its indecent intersection that crushes pedestrians. While the motorists are already consumers, pedestrians represent citizens in their simplest expression, vulnerable in their flesh, fragile, small, but so powerful when they agglomerate and transform into demonstrators.

On the other side of this cut made in the flesh of the city, Gouraud Street’s rebuilt section changes texture and loses its soul. Here the urban text of this long street unravels. From a historical place, stratified, inhabited, by crossing this immense crossroads, our street is transformed into a non-place. Here, nothing catches the eye, nothing questions, nothing surprises, except the brutality with which, in a few steps, we pass from one world to another, from the city to the non-city, from Beirut to Solidere. This is where the strolling stops and the objective, neutral, disinterested passage through the spaces it crosses begins. Walking becomes objective in that it can no longer be a goal in itself, but now must have an objective outside itself.

Here, the city is no longer. And, after hearing words spoken with accents, sentences in Arabic mixed with Amharic, Sinhalese, Tagalog, Armenian, Turkish, English and French, all these Lebanese languages that intermingle and graft each other along this Beirut Street, this global street, after hearing all this, while passing Georges Haddad Street, all of a sudden, it is silence. All we hear is the wind and the passing cars. Because, in the empty center of Beirut, nobody walks, nobody exchanges, nobody talks, nobody lives.

Camille Ammoun is a writer, public policy consultant and member of Beyt el-Kottab. His latest book is Octobre Liban (in French; Éditions Inculte, 2020). His column appears monthly in L’Orient-Le Jour and L’Orient Today.

This column was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour.