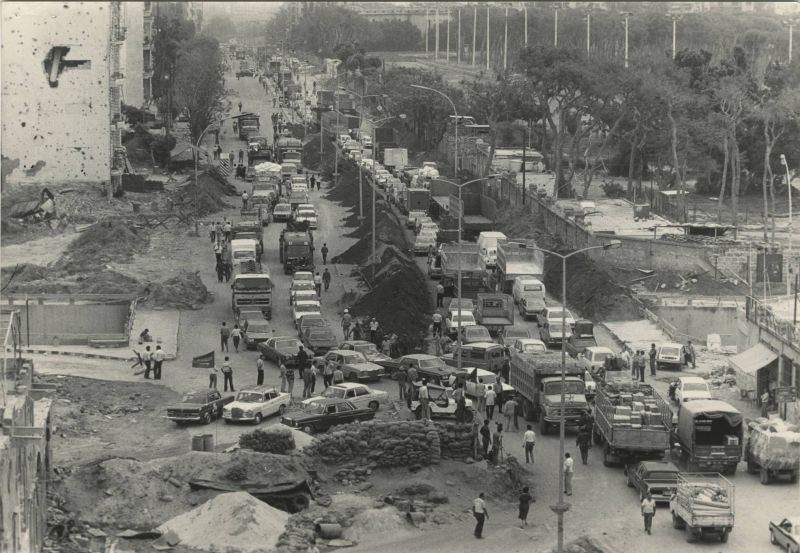

The intersection of Bechara Khoury Boulevard and Corniche al-Mazraa in 1984, with the Beirut Hippodrome visible in the background. (OLJ Archives)

BEIRUT — While a recent proposal to split Beirut into two municipalities does not appear to have gained much traction, the capital city has long been physically, if not administratively, divided. Rather than being connective tissues, its roads often form barriers.

Ghadi Bou Samra, an animator, used to commute from Hamra to Sodeco, a 3.4-km distance that should have been walkable. But there was no direct path he could take, as the pedestrian routes are cut by the massive Ring Bridge, so he would ride a cab instead. On the way back, he would have to crisscross busy roads from Sodeco to Monot to downtown to Hamra to get home. One time when he made the mistake of walking his dog in the area near the Ring, "I had to carry him [along some stretches], because it was way too dangerous,” Bou Samra said.

Podcaster Ronnie Chatah, who for 15 years led a tour group around Beirut, said: “The biggest challenge for me was trying to find a pedestrian-friendly way to get groups of people to cross the city.”

For instance, “I never wanted to risk anyone’s life by crossing from Spears to Achrafieh through the Ring.” But he kept trying to find new routes, he said, because “the insistence on walking in Beirut is the only way you’ll love the city.”

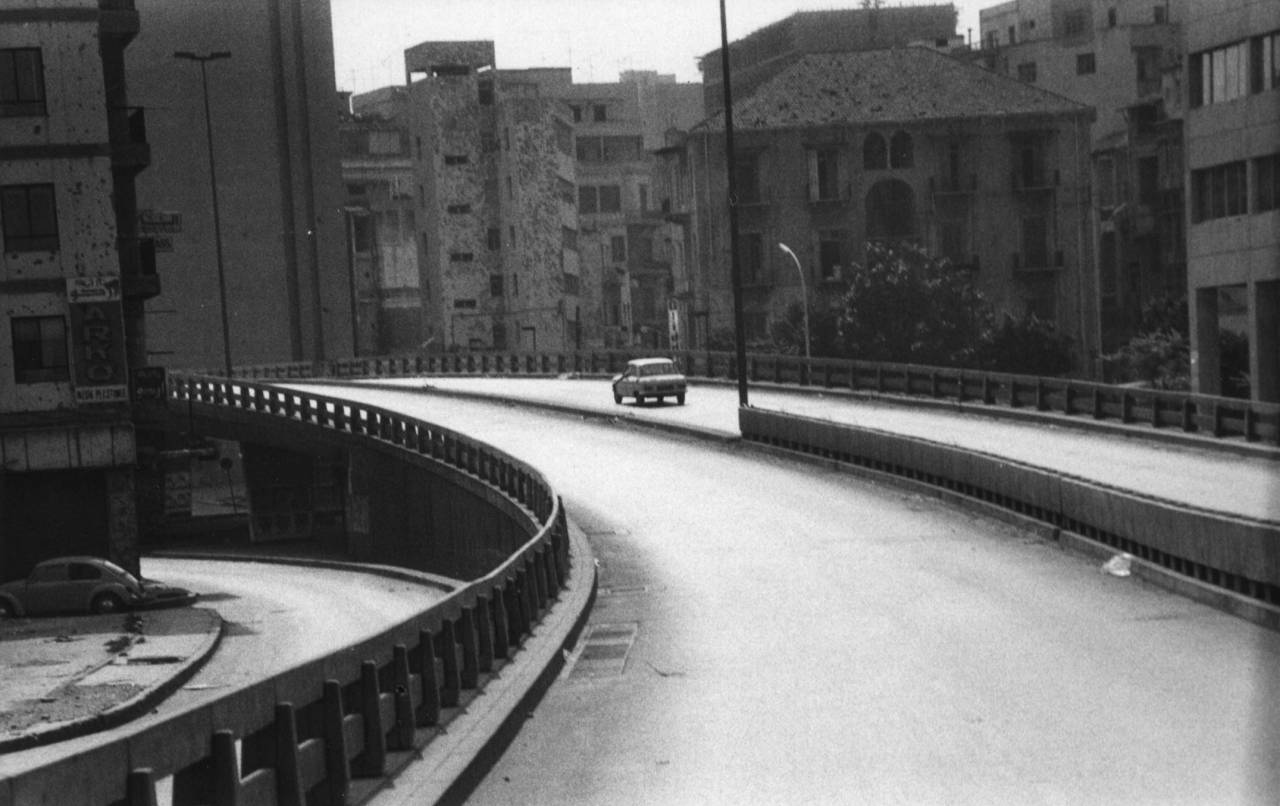

A section of Fouad Chehab Boulevard in the 1980s. (OLJ Archives)

A section of Fouad Chehab Boulevard in the 1980s. (OLJ Archives)

Aside from making Beirut less walkable, the city’s major thoroughfares have also served as de facto borders that divide up the capital. While many assume this to be a legacy of the Civil War, most of these infrastructure projects in fact predate the war and their original purpose was not to divide the city.

Urban designer and researcher Ali Khodr told L’Orient Today that the major thoroughfares that divided the city during the Civil War and afterward were, ironically, designed by people who were thinking about connectivity, functionalism and ease of business.

'One straight line'

The modern footprint of Beirut’s road network was built in two phases. The first phase, which took place in the 1950s, Khodr said, was aimed at connecting the different communities in Beirut.

Khodr noted that many of the foreign urban planners working in Beirut before the Civil War “aimed towards urban connectivity, as opposed to segregating the city.”

Khodr pointed to Elias Sarkis (Independence) Avenue, which was the first uninterrupted lateral road between Verdun and Sassine. Before the road was constructed, he said, “You would have to go to the city center, because everything radiated outside of the city center and there were no straight connections between these neighborhoods.”

A section of Bechara Khoury Boulevard in 1980. (OLJ Archives)

A section of Bechara Khoury Boulevard in 1980. (OLJ Archives)

Now it was possible to traverse “in a straight line through communities that encompassed the Druze, Syriac Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Sunnis and Shiites,” he said.

There was a similar intention behind Corniche al-Mazraa, another wide road built before Elias Sarkis avenue on church land that connected neighborhoods housing multiple sectarian communities.

The second phase of road construction was aimed at complementing the growth of Beirut in the 1950s and 60s as a regional financial and tourism hub. Urban planners from that period envisioned road works to complement public housing projects that would be mixed in character, but the plan was only partially implemented, leaving out the housing.

This era saw the construction of the major arteries we know today, such as Fouad Chehab, Bechara El Khoury and Salim Salam.

Khodr says the main idea was: “I want to get from the airport to the city center in one straight line. And when I get to the city center, I want to be able to go around the city center in a straight line, or at least in a loop. All of these are things that we need to consider.”

Cars as 'freedom'

Perhaps the starkest of these physical divisions is the Ring Bridge, also known as Fouad Chehab Boulevard, which connects — and separates — two of Beirut's busiest neighborhoods, Hamra and Achrafieh. It has been a flashpoint for strife, both during the Civil War when it was the main route between East and West Beirut, and in times of peace.

Many remember the contested nature of the Ring Bridge during the Oct. 17 uprisings of 2019, when Hezbollah and Amal supporters attacked protesters who had occupied the streets in and around Downtown Beirut.

The genesis of the Ring came in 1962, when the government began expropriating houses and land on what was then the southern border of Beirut’s historic core. Jan Altaner, who researched this topic for his master’s thesis at the American University of Beirut, told L’Orient Today that “the idea behind making a ring around old Beirut started in the French Mandate with French planners like Michel Écochard in the 1940s, to solve bad circulation that was clogging downtown.”

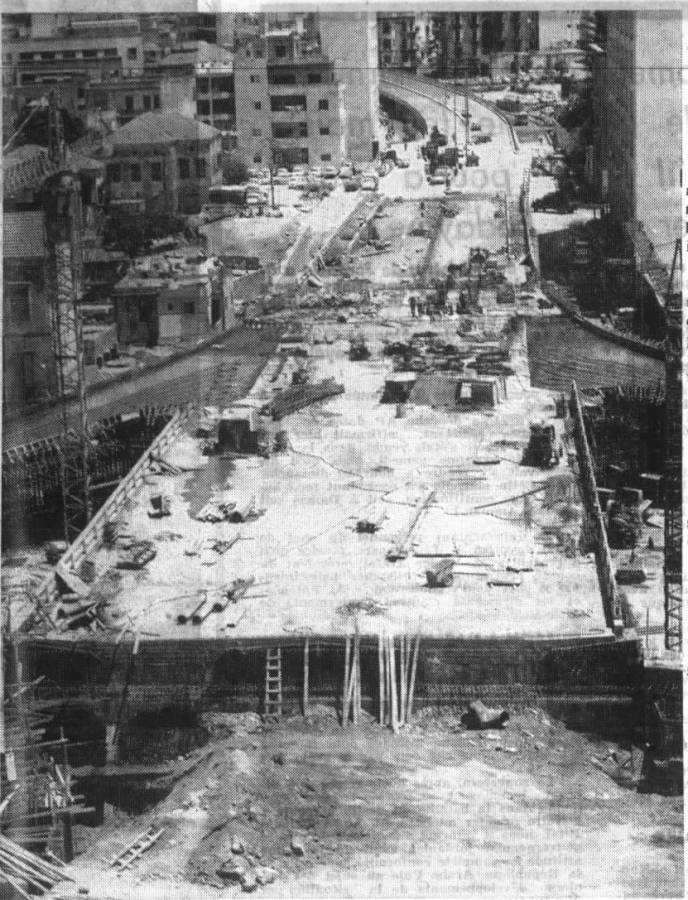

Beirut's Ring Bridge under construction in 1970. (OLJ Archives)

Beirut's Ring Bridge under construction in 1970. (OLJ Archives)

He added that back then if a car wanted to get from Tripoli to Saida, “it often had to pass through the center of Beirut adding to its congestion.”

Écochard would later draw up plans for other road projects.

According to Altaner, car importers also played a role in propagating individual car ownership premised on the idea to have a “bourgeois class built up of individuals who drive their own cars to experience freedom.”

To make way for this new infrastructure project, many heritage buildings were destroyed, including mansions in the Zoqaq al-Blat area, with the government using eminent domain to take the properties and compensate their former owners.

Aside from homes being destroyed, construction of the Ring led to sectarian enclaving. Many residents of the adjacent Bashoura neighborhood to this day claim that the road was built to isolate the growing Shiite community there. Altaner is skeptical of this hypothesis, however, because the Ring was originally proposed at a time when the area was more religiously diverse.

Another major road that split up Beirut was Bechara El Khoury Boulevard, which would be a site of sectarian strife in 2008 as it divided partisans supporting Hezbollah and those supporting Hariri. Built starting in 1963, the road was a massive undertaking. The aim was to cut a thoroughfare from the airport to the pines of Horsh Beirut to the city center. To do so, the government expropriated houses through eminent domain, paying LL12 million (worth around $4 million then) for around 600 homes.

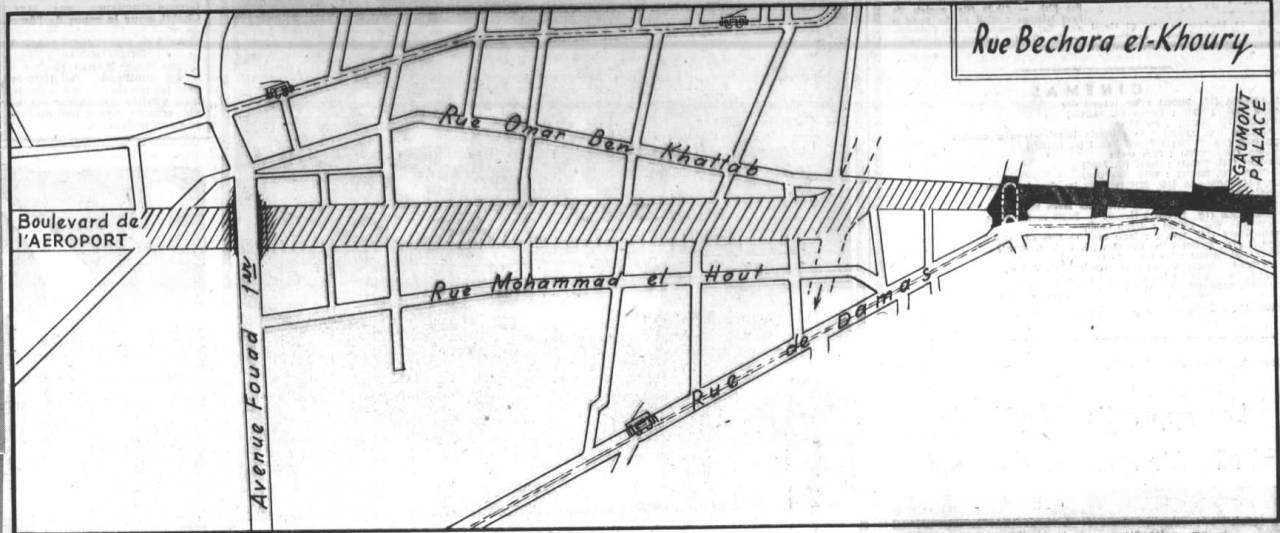

The 1963 plans for Bechara El Khoury Boulevard. (OLJ Archives)

The 1963 plans for Bechara El Khoury Boulevard. (OLJ Archives)

Construction of the road, Khodr said, “cut across some of the most sensitive neighborhoods in the city that were very much on the lower scale of the socio-economic classes.”

More division after the war?

Though the purpose of all of these roads was ostensibly either connective or functional, they were later integrated to the frontiers that emerged in the wake of the 1958 civil strife and later the 1975 Civil War.

Corniche al-Mazraa and Elias Sarkis Avenue became the sites of militia checkpoints. In the case of the latter, the Barakat Building became an infamous civil war snipers nest and is now a cultural center, Beit Beirut.

The so-called Green Line, comprising Damascus Road and the area between it and Bechara El Khoury Boulevard, formed a no man’s land that stretched from the north to south of Beirut, separating Muslim from Christian Beirut with many militias’ checkpoints along the way.

Khodr noted that the seeds for these Civil War frontiers were rooted before the start of the war, in the 1958 civil strife between groups supportive of US-allied president Camille Chamoun and groups that backed pan-Arabist Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

A view of the Bechara Khoury Boulevard tunnel, near Horsh Beirut, in the 1980s. (OLJ Archives)

A view of the Bechara Khoury Boulevard tunnel, near Horsh Beirut, in the 1980s. (OLJ Archives)

“People tend to really underestimate the power that that moment of violence inflicted across the entire city,” Khodr said. “We know for a fact that Beirut before the Civil War was already a divided city; there were already preset quarters for certain communities, where they're going to live or where they were allowed to live.”

The “in-between neighborhoods” between these quarters, and particularly between Ashrafieh and Hamra — including Corniche al Mazraa, Bachoura, Zoqaq al-Blat and Monot — became “zones of violence, or zones of upheaval,” Khodr said.

Roads a ‘cheaper’ option

Although the checkpoints that had divided Beirut into two parts were removed after the Civil War ended, it remains difficult to traverse the city from end to end on foot.

In the wake of the war, some of the infrastructure projects completed during the reconstruction period further entrenched the physical divisions. Some roads were widened, including Bechara El Khoury, and Fouad Chehab was expanded with tunnels and overpasses at a time when many other cities abroad were starting to focus on making their streets more pedestrian-friendly instead of giving more room for cars to roam.

Sam Bechara and his running group avoid these routes: “There’s nothing running friendly about these areas.” He added that “in other countries, you can leave your house and start jogging from there, but in Lebanon you have to take a car ride and then jog…it’s really not safe for runners.”

Instead of taking a more pedestrian-friendly approach to reconnect the city after the war, Khodr said, in the wake of the Taif Accords, plans focused on “stitching the city back together through winding the roads and connecting it to the airport.” All this was for show, to create an image that “everything is well and good that we’ve overcome the civil war.”

Khodr noted that “it was easier and faster and cheaper to work on the roads” than to reconstruct the railway, but added that in the long run this strategy ended up costing more because the roads were built poorly.

New arteries, such as the Airport Road, were also built as Beirut hosted events like the Pan-Arab games in 1998 and the Asia Cup in 2000, which Khodr said were intended more to give Beirut an image makeover for the outside world than to properly connect the city for its residents.

Ironically, many of these roads were built to absorb the increasing traffic, but ended up adding to it, in a phenomenon known as induced demands.

In more recent years, there have been some attempts to increase walkability in the city, such as the proposed Fouad Boutros Park, a promenade extending from Mar Mitr in Achrafieh all the way to Mar Mikhael. This project replaced the planned 1.3-km Fouad Boutros Highway project after many activists protested against it, arguing that it would further destroy the city and increase traffic.

The campaign for the promenade utilized the 2006 amendment to Law No. 58, under which projects intended for the public interest can be substituted with counter-proposals, so long as they also benefit the public. However, the park proposal has remained on hold for years.

In some of the areas that are ostensibly most pedestrian-friendly, like Armenia Street in Mar Mikhael, Chatah, the walking tours leader, noted that restaurants use the sidewalk for additional capacity, impeding foot traffic.

“The luxury of walking in the city is removed and with that a city loses its charm and an appreciation for a history you can only see when you are walking,” Chatah said. Without the ability to walk and look around without focusing on traffic, he said, “you lose touch with your city.”