Straw mats laid out in the courtyard of the Khodr Mosque for Friday prayers (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — Dozens of mopeds are parked around the gate of the Khodr mosque for Friday prayers.

The congregation overflows outside the place of worship’s glass encasing into its courtyard, where wicker carpets are laid for worshippers who angle for a spot under the metal canopy set up to block the sun.

It’s so crowded that the prayer service spills over into the adjacent gas station, right next to the busy highway. An embassy motorcade passes through with sirens ringing. A Toters delivery driver lays down his jacket in place of a prayer mat on the hard asphalt.

After their religious duties are done, the congregation leaves the mosque’s compound in droves. Many pass by a cart hawking shaabiyat (baklava) to buy a treat. Others climb up the pedestrian bridge back to Karantina, while some board the bus destined for Dora and the greater Metn area, back to work.

Mar Mikhael, a predominantly Christian neighborhood that has become the center of a raucous nightlife scene in recent years, is known more for the crowds that flock to its bars on Friday night than for those who flock to its mosque on Friday afternoons.

But the Khodr Mosque — on the north end of Mar Mikhael, next to the highway, with the B018 nightclub on the other side, and the Armenian quarter of Nur Hajjin to the east — is an integral part of the neighborhood.

Although relatively unknown to most, and shielded from the view of passersby because of a Total gas station, the mosque is one of the earliest known buildings in the area. It was built back when Beirut’s boundaries did not exceed what is today known as Martyrs’ Square.

A Total gas station now obscures the Khodr Mosque from view. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa/L'Orient Today)

A Total gas station now obscures the Khodr Mosque from view. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa/L'Orient Today)

Many sources date the mosque to at least the crusader period and possibly as far back as the Byzantine period, when it was a chapel. Back then it bore the name of St. George, and for good reason. Legend claims that this is the location where George slew the dragon.

Today most people, if they think about St. George’s connection with Beirut, would think of the hotel that bears his name on the waterfront. The connection to the mosque is lesser known.

According to Marlene Kanaan, a professor of philosophy and civilization at the University of Balamand and an expert in hagiography, there are many stories about the origins of the saint, but his connection to Beirut can be traced to the 15th century Mamluk historian, Saleh Ben Yehya.

In his book Tareekh Beirout, Ben Yehya narrates that a dragon lived inside the lagoon of the Beirut River. When the dragon tried to kill the daughter of the Roman governor of Beirut “she prayed to God for her deliverance. St. George revealed himself to her, and when the dragon appeared the saint approached it and killed it.”

A chapel was built on the site where the dragon was slain. Ben Yehya added that “The citizens of Beirut, Muslim and Christian, commemorate this event by going to the river on the day of his feast, April 23.”

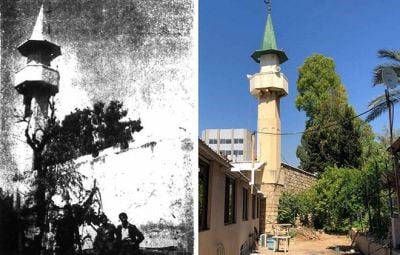

Side-by-side photos show the Khodr Mosque from the same spot in 1953 and 2022. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa/L'Orient Today)

Side-by-side photos show the Khodr Mosque from the same spot in 1953 and 2022. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa/L'Orient Today)

St. Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine the Great, is said to have given the chapel a white marble pillar on her way back from Jerusalem. It is said that people with rheumatism would touch it in hopes of a cure.

When the crusaders arrived in the 12th century, they encountered the eastern Saint and began to appropriate him, most notably on the flag of England which bears the cross of St. George.

The crusaders built a chapel on the site where the mosque is today — then outside of Beirut’s walls — that included a crypt, a dome and a monastery.

There is debate over whether the structure was built over the remains of the Byzantine chapel. Archaeologist Patricia Antaki told L’Orient Today that “without archeological excavations, it cannot be determined for sure.” She points that the large carved sandstones on the oldest part of the mosque are an indicator of crusader architecture, however, there is a possibility that they were reused from buildings of that period.

What is clear is that by 1570, the chapel, which by then was Greek Orthodox, started sharing the building with the Maronites. Then, in 1661, owing to the Christians’ inability to pay religious taxes (dhim), the church was expropriated by the governor of Saida, Ali Basha, who converted it into a mosque and renamed it Khodr.

This was no coincidence.

Kanaan said that the name George “comes from the Greek term for ‘cultivator,’ and that’s where the relation with Khodor emerged because everything he touches turns to greenery.” She noted that in some towns in Lebanon, residents refer to St. George as Mar Gerges al-Khodor.

Ali Bitar, who has been the imam of the mosque for the past three years, has a different take. He said it’s named Khodr after Nabi Khodr, the companion of the prophet Moses in Ibn Kathir’s Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyā (Stories of the Prophets). He also asserted that the mosque was not formerly a church.

But Kanaan says that the mosque’s conversion is corroborated by Anglican bishop Richard Pococke, who wrote in his travelog while passing through Beirut in 1745 that “we came to the place where, they say, Saint George killed the dragon which was about to devour the king of Bayreut’s daughter: There is a mosque on the spot, which was formerly a Greek church.”

There he encountered the pillar of St. Helena being used in a healing ritual involving “one of the Turks that was with me; who [s]itting down on the ground, the religious per[s]on, who had the care of the mo[s]que, took a piece of a [s]mall marble pillar, in which, they [s]ay, there is an extraordinary virtue again[st] all [s]orts of pains, and rolled it on the back of the Turk for a con[s]iderable time.”

Additionally, Christians who would visit the mosque for its 20-foot domed water well. Kanaan said that many used to bathe in its waters to help with fertility. She recalled the story of her own mother, who in the 1950s, after a few years of marriage, was having trouble bearing children. To deal with this issue, her close relations took her to the Khodr Mosque to wash in the waters of the well.

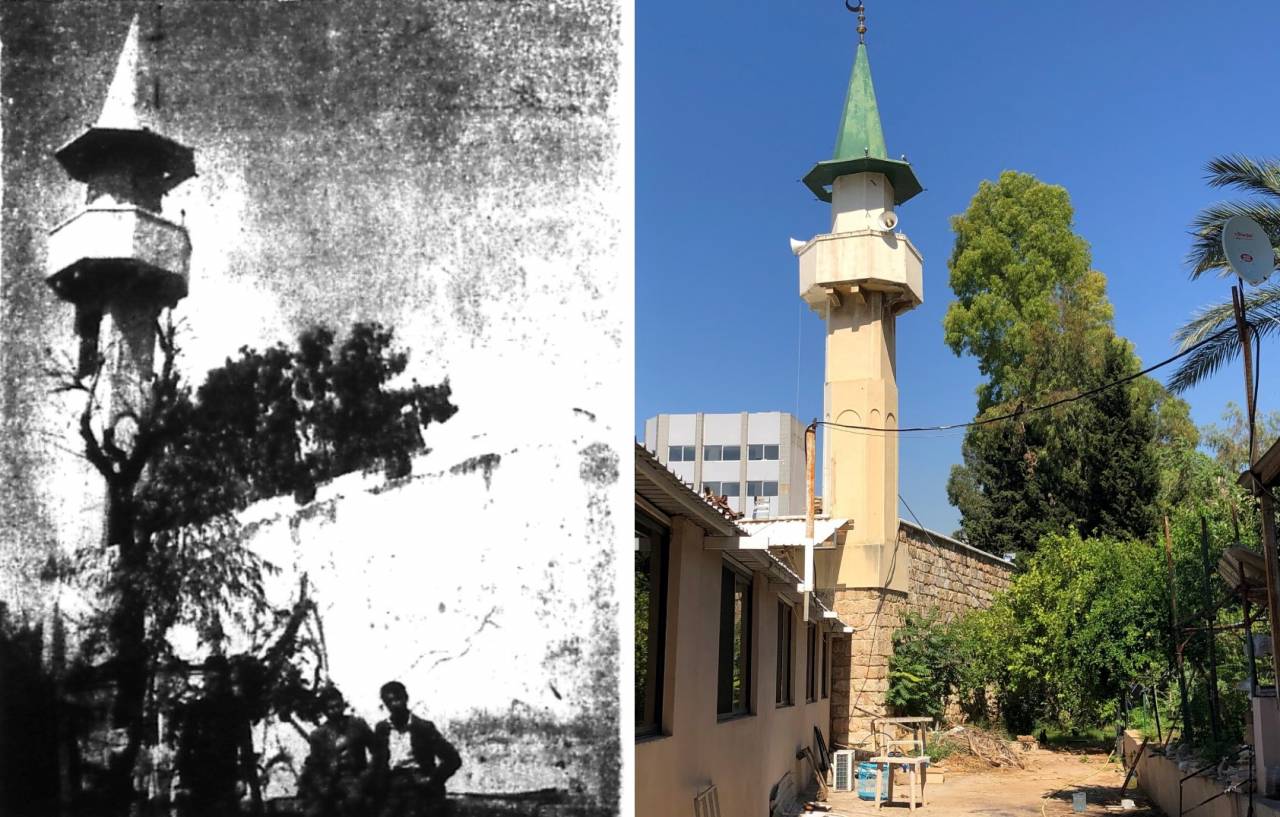

The Khodr Mosque's domed well as it looked in 1953. (Credit: Philip Conde)

The Khodr Mosque's domed well as it looked in 1953. (Credit: Philip Conde)

But when Kanaan wanted to see the well in 2008, it was no longer there.

How the Mosque disappeared in plain sight

In 1895, the Mar Mikhael train station was built right next to it. Then, starting in 1907, the process of the mosque’s enclaving would begin, as the tracks for the tramway would be laid right across it. A 1922 French Army map shows how the tracks enclosed the place of worship on the north, west and southwest.

Writing in 1953 for The Daily Star, American reporter Bruce Conde had a hard time finding the mosque which involved “getting off the Nahr tram about half way down the hill just before reaching the river” and walking one block north. He was able to find it by spotting the minaret.

When Beirut’s trams were phased out in 1964, huge highway projects took their place, further obscuring the mosque from view.

In a sense, the car economy contributed to the obscurity of the mosque.

Unlike the railway, the highway brought cars constantly, not periodically like trains and trams. This is not to mention the gas station and the tire store built nearby to serve cars.

As a result of this enclaving, the mosque experienced a decline in popularity as a site of pilgrimage and reverence.

This was supplemented by the removal of the mosque's relics: In the early 1950s, Conde reported that the Khodr’s then Imam, Sheikh Mohammed Rashid Khalidy, had the marble pillar removed, and handed it over to the Wakf administration of Dar al-Fatwa. When contacted by L’Orient Today, Dar al-Fatwa officials said they had no knowledge of the matter.

Additionally, the domed well was demolished and paved to make way for a playground for the al-Khodor primary school built next door, as it was feared that children could fall into it.

While on break in Beirut in 1971 from covering the Vietnam War, United Press International correspondent Helen Gibson reported for Aramco World Magazine that the locals she spoke to said that they hadn’t seen pilgrims come to the mosque since the 1950s due to the “noisy garage.”

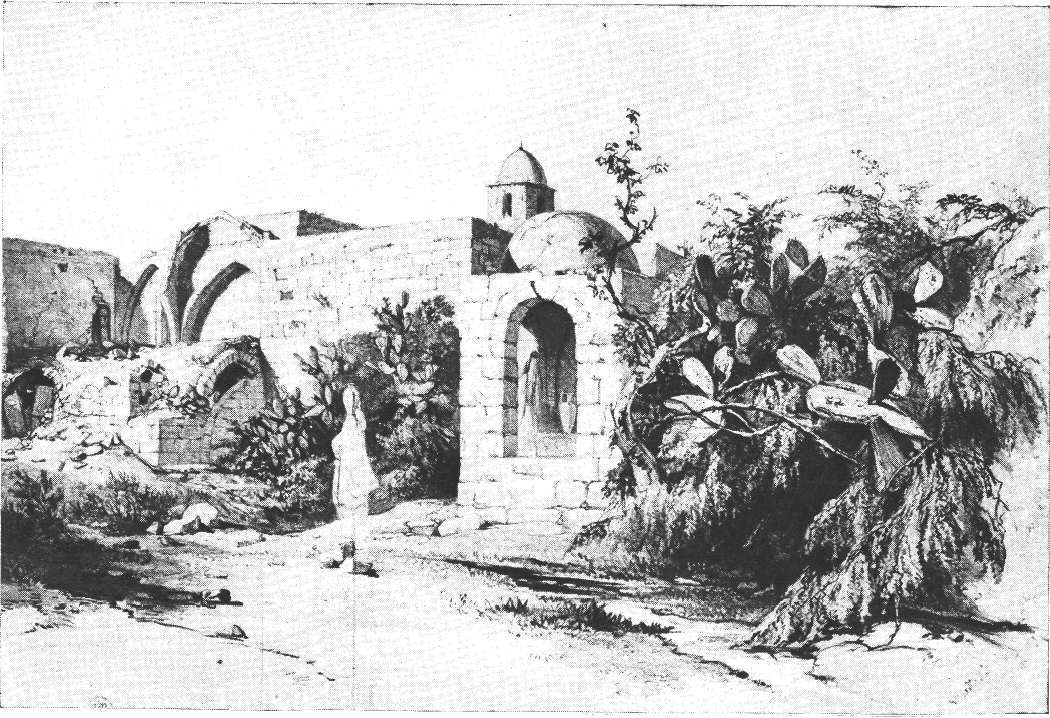

Sketch of the Khodr Mosque by French archaeologist Léon de Laborde drawn in 1827.

Sketch of the Khodr Mosque by French archaeologist Léon de Laborde drawn in 1827.

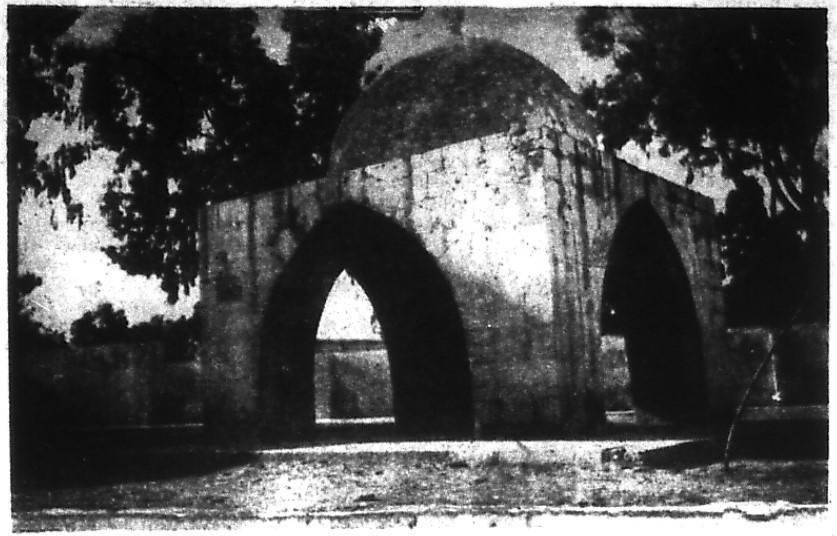

Unsurprisingly, the fabric of the building reflects these changes over time. According to a sketch by French archaeologist Léon de Laborde in 1827, a huge portion of the original Khodr mosque was demolished.

What was left was the south half of the mosque, whose interior consists of a vaulted ceiling with a semicircular apse on the eastern end, a mihrab that points to Mecca to the south end and an arched front door that opens to an extension of the mosque completed in 1934 and includes a triple-arched portico at the northern entrance.

A modern minaret was built in 1949 by Prime Minister Riad al-Solh which contrasts sharply with the crusader wall it sits on.

The semicircular apse on the eastern end of Khodr Mosque's interior. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa/L'Orient Today)

The semicircular apse on the eastern end of Khodr Mosque's interior. (Credit: Mohamad El Chamaa/L'Orient Today)

Bitar said that during the Lebanese Civil War, the mosque and the school were taken over by the Lebanese Forces, and the school buildings were handed over to the army after the end of the war.

One lasting legacy the mosque is administrative, as it lends its name to the Khodr sector in the Beirut municipal framework, stretching from Armenia Street to Karantina.

Despite its obscurity, today, the mosque still has a significant role. Much of its congregation comes from the surrounding areas across the Beirut River, all the way into “Dora and Jdeideh, and in some cases Brummana and Jounieh” says Bitar, owing to a lack of mosques in those areas.

It also serves delivery drivers and waiters who work in Mar Mikhael and Gemmayze. The worshippers are of different nationalities — during the Friday sermon, the mosque’s imam asked God to save Lebanon and also Syria, in a nod to the large Syrian crowd.

After the Friday prayers were over, some stayed to rest and escape the summer sun, owing to a lack of public space in the area.

Ahmad, a 71-year-old man from Syria, who was reading the Quran after praying, said he comes to the mosque three times a day. He’s been doing so since moving to Lebanon ten years ago, staying after prayers to avoid the spate of power cuts in the country.

Khalid Sa’id, a long-time resident of Karantina, has known the mosque since childhood, “we used to pass by it when we herded sheep from the train station to Karantina,” he told L’Orient Today. His family is buried near the mosque, but after the 1976 Karantina Massacre, he was displaced from the area. After returning in the 1990s, Sa’id said “we found that they were removed, we don’t know what they did with them," but are in talks with Dar al-Fatwa over the matter.