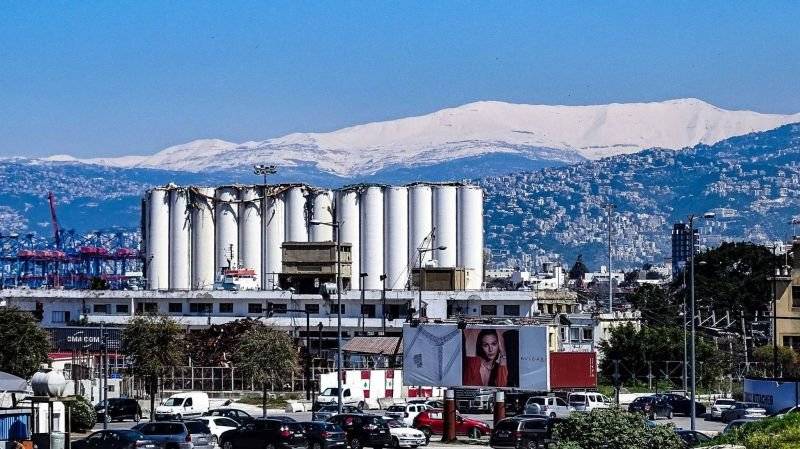

The Beirut port silos and Mount Sannine, March 23, 2022. (OLJ/Camille Ammoun)

Today, it has been two years since I was a silo. For two years my grain has been fermenting to the point of spontaneous combustion in the humid heat of this second summer after summer zero. This smoldering fire, feeding on itself for weeks, is threatening my already tilting cylinders, I am told, by several millimeters a day. Two of them collapsed in a din of dust. Others will follow. I don't know how much longer I can keep up the illusion.

I remember that morning, a few months after the disaster, when my grain bloomed. It grew on the rubble of the beach formed by the crater. For some, it was a sign of hope. But this bloom was a sad one. This grain was not meant to germinate but to be made into flour, then into dough, then into bread. It was an unhealthy blossom, like the flowers that are now growing in areas of the planet that have been, for thousands of years, covered with eternal glaciers.

You have destroyed everything, spoiled everything, dirtied everything. You are all the same, here and anywhere else. You are short-term profiteers with no vision or aim besides earning more, consuming more, eating more. But it is about my evisceration that I am talking here, the lives, the streets, the objects, the stories, and everything that was, on that 4th of August 2020, ravaged by the relentless blast of your utter incompetence and your insatiable greed of gluttons.

My ruin, and the misfortunes that came along with it, were perhaps already written in the structures of my cylinders since I was erected in September 1968, only a few months after the student demonstrations that had led to the creation of free universities. It was spring, I was in construction, and the students were in the streets. Everything was in place for tomorrows to sing. But 1968 was also the year of the first Israeli attack on Beirut. It took place in December, when my cylinders were just starting their conversation with the dazzling whiteness of Mount Sannine. On December 28, 1968, an Israeli commando attacked the airport, destroying a dozen civilian planes. There, it was written: tomorrows would not sing, or only erratically, or only out of tune.

But I will try to stick to my fatal encounter with this Moldavan-flagged vagrant cargo ship, the Rhosus, and especially with its ammonium nitrate cargo. Sold at auction by its bankrupt Georgian manufacturer, Rustavi Azot, it was bought by a UK-registered shell company, Savaro Ltd., which promised to sell it to the Fábrica de Explosivos Mozambique. But, with empty coffers, unable to pay for passage through the Suez Canal, the Rhosus stayed at Beirut where it was abandoned by its captain and crew, by its owner, its charterer and even by the Mozambican sponsors of the cargo. On October 23 and 24, 2014, the Beirut port authorities unloaded the bags of ammonium nitrate in warehouse number 12. On February 18, 2018, the Rhosus sank on site.

I don't know if Beirut was the final destination of the cargo and if this Fábrica de Explosivos Mozambique story was only a smoke screen. I don't know if the ammonium nitrate in warehouse number 12 was siphoned off for years, because, according to some reports, if the totality of the cargo had exploded, the whole city would have been wiped off the map. I don't know where the spark that caused the fire and the explosions came from. I don't know if the accident was intentional, or if a succession of human errors and negligence led to this catastrophe. The only way to sort out the real from the fake is to make good use of the most elegant, the most complex, yet the most fragile of all human inventions: the independence of justice.

On August 4, 2020, at 6:07 pm, the Rhosus cargo exploded, devastating half the city, killing more than 200 people, injuring more than 6,000 and displacing 300,000 inhabitants of Beirut. It was an atypical event, both surprising and predictable, staggering and inevitable. One of the biggest non-nuclear explosions in history. Here, at my feet, in the heart of the city I was supposed to feed with my grain. First, the intense heat and the infernal blast that sucked the sea away and dug a meteorite-sized crater. Then my cylinders, like bridges hanging in nothingness between the deaths of yesterday and those of today, vomited their grain into the sea; their grain, but also lives, houses and streets. Gigantic boats went down on their sides. The majestic mountains trembled. A huge mushroom of red smoke rose above the city. It was visible from everywhere. After the shock, the stupefaction, the collapsed walls, the smashed roofs, the blown-out windows transformed into millions of projectiles, the dead, the blood, the sliced flesh, the dismembered bodies, the impossible griefs, after all that (as if “after” could still have a meaning) after all that, then, an immense sadness, a feeling of absolute abandonment, of infinite loneliness and of an appalling dereliction invaded the guts. Beirut was over.

I am no longer a silo. Tomorrow, perhaps, I will be a memorial, but more likely, I will disappear from your urban landscape. I am no longer a silo. I am a wreck, and I am a witness. A witness to the horrors perpetrated by men, the same men for decades. I saw assassinations, I saw living bodies tied to a rope and dragged by cars, I saw snipers shoot at everything that moves, cats, men, children, I saw car bombs and swift executions, I saw indiscriminate bombings and trictrac games played in the morning by nighttime enemies, I saw fear in the eyes of children and parents smiling to protect them, and I saw that these smiles were sincere, I saw the city split and from inside the fault a forest grow, I saw young people dancing in basements and old people telling each other that everything was fine. I saw in 1982 the departure of the Palestinian fighters and I said to myself: this nightmare is over; I saw in 1990 the country reunified and I said to myself: this nightmare is over; I saw in 2000 the rout of the Israeli army and I said to myself: this nightmare is over; I saw in 2005 the withdrawal of the last Syrian soldier and I said to myself: this nightmare is over; then, in 2019, I saw the emergence of a civic conscience and a political opposition and I said to myself: this nightmare is over. But since this 4th of August 2020, when I almost died, I know that the everlasting Lebanese war will only end when those who waged it are no longer in power. I was the belly of Beirut; I have become its memory.

Camille Ammoun is a writer, public policy consultant and member of Beyt el-Kottab. Latest book: 'Octobre Liban' (in french ; Éditions Inculte, 2020). His column appears monthly in L’Orient-Le Jour and L’Orient Today.

This column was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour