The silos at the Beirut port stand devastated in the aftermath of the Aug. 4, 2020 explosion. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BEIRUT — A little more than a year ago, a trio of heavyweight international organizations announced what was billed as an innovative new structure for channeling aid to Lebanon, which was then still reeling from the immediate aftermath of the Beirut port explosion.

The price tag to rebuild the capital and help residents and business owners recover from the direct and indirect effects of the blast was projected to be in the billions of dollars.

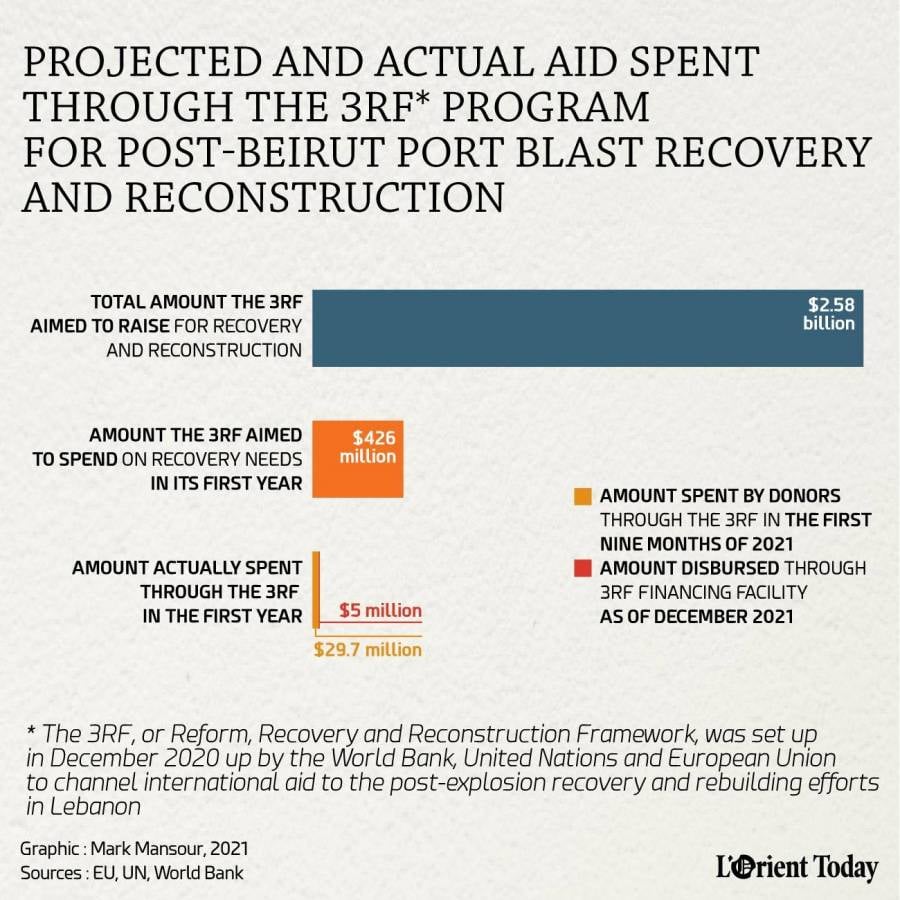

The Reform, Recovery and Reconstruction Framework, or “3RF,” a joint project launched by the World Bank, United Nations and European Union in December 2020, aimed to mobilize some $426 million in the first year for immediate recovery needs such as restoring housing and businesses damaged by the blast.

While funding for long-term reconstruction projects would be contingent on government reforms, the international organizations said the funding for these short-term needs would come with no strings attached.

A year later, however, a fraction of this amount has been spent on the ground. Key projects have been delayed by bureaucratic roadblocks from the government side — an initiative to help small businesses damaged in the blast was held up for months because the Finance Ministry had not issued a letter needed for approval of the project — but also by the reluctance of donors to give more to Lebanon, despite the initial promise that immediate recovery projects in damaged areas would be funded regardless of the government’s actions or inaction. And the tracking of the funds that have been spent is often unclear.

In November, nearly a year after the launch of the 3RF, international and local officials announced the launch of the first project to be funded through a World Bank-managed funding facility set up through the framework: a $25 million program to provide grants of up to $25,000 to some 4,300 small and micro-sized businesses within a five kilometer radius of the port. However, the project is still in the registration and vetting phase, and no assistance has yet gotten to the business owners.

The aid, if it comes, will be welcome but late for people like Ali Diab, who for 22 years ran a hair salon in a rented storefront in Karantina with his brother. The explosion left their building standing but blasted through the shop’s windows and doors, collapsed the ceiling and ruined equipment.

In the aftermath, the brothers paid out of pocket to make the needed repairs to the store so they could reopen.

“I spent everything I had saved and borrowed money to fix the shop,” Diab said.

Ali Diab cuts a client's hair in an adapted room at his home. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Ali Diab cuts a client's hair in an adapted room at his home. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

When, a year later, the landlord declined to renew their rental contract, the brothers did not have the money to move to another rented storefront, particularly given the inflation in rental prices in the area — which Diab attributes partially to the influx of NGOs after the explosion, some of which rented spaces in Karantina at higher rates than the old tenants could pay.

Today, he lathers and trims his customers in the cramped living room of the one-bedroom apartment where he lives with his wife and three adolescent sons.

The move has substantially reduced his customer base, Diab said; many of his elderly former clients are unable to climb the two flights of stairs to the apartment, while others are uncomfortable having their hair cut in what is obviously a family home. From 20 to 30 clients a day in the old shop, Diab said, he now gets four or five. And even in these reduced numbers, the daily parade of strangers underfoot in their tiny apartment over the past three months has put his wife on edge.

“But what else can I do?” Diab said. “We’re living and we have to go on somehow.”

An attempt to organize the response

In the immediate aftermath of the port explosion, there was a rush of assistance to blast-damaged areas by grassroots initiatives funded by the Lebanese diaspora and other well-wishers, alongside donations provided by UN agencies, international NGOs and various donor countries, and some limited compensation distributed by the Lebanese government.

While sorely needed, the efforts were also widely criticized as being chaotic and uncoordinated, resulting in some people receiving aid from multiple organizations while others in need were entirely overlooked.

Even the tracking of where the aid was spent was, in some cases, opaque.

While the flows of private donations into the country have been largely untracked, many of the cash and in-kind donations given by governments and international organizations were reported via either the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs or via the Lebanese government.

The former reports a total of $317.7 million given by international donors to the post-explosion response (not including the 3RF) since August 2020 , with about $167 million coming through an appeal issued by the UN and the rest as bilateral donations to the Lebanese government or through other mechanisms. Out of the money given through the UN appeal, for which more detailed information is available, the largest donor was the European Commission, which gave more than $40 million — mostly to UN agencies providing shelter, health and cash assistance to explosion victims — followed by the United States and Qatar.

Meanwhile, the French government, along with the United Nations, convened a fundraising conference days after the explosion, where President Emmanuel Macron’s office announced 257 million euros had been pledged; four months later, Macron’s office said that 280 million had actually been disbursed, but without giving a breakdown of the donors or the projects the funding had gone to.

When asked for more details on the donors that had contributed and projects funded, a French embassy spokesperson in Beirut said the French had not tracked the breakdown of the funding and referred L’Orient Today to OCHA. However, OCHA officials said they had officially tracked only the portion of the funds that came in via the UN-organized appeal for humanitarian aid. Meanwhile, the Lebanese government’s donation tracking mechanism shows $41 million from Kuwait and $50 million from Qatar listed as having come via the French conference, but does not specify how the funds were spent.

Apart from fuzziness in the reporting of the post-blast aid funds, a sizable portion of the value of the funds may have been siphoned off by the banking system due to the multiple exchange rates that have resulted from Lebanon’s financial crisis.

The 3RF program, launched in December 2020, was supposed to provide a framework to coordinate what had previously been disconnected aid efforts, give more transparency and input to local groups, and reassure international donors who were reluctant to give directly to the Lebanese government, which many of them saw as corrupt and incompetent.

“The 3RF is actually a new way of working, which is to bring government, the private sector, civil society and the international community together into one mechanism, which did not exist before,” the World Bank’s regional director, Saroj Kumar Jha, told L’Orient Today.

In total, the mechanism aimed to raise more than $2.58 billion, with about $2 billion of that being for longer-term reconstruction projects, contingent on economic and governance reforms that have largely not taken place.

The bulk of the funding to be disbursed through the 3RF structure was intended to come via a World Bank-managed financing facility, with projects being developed and monitored in collaboration with advisory and oversight groups that include representatives of civil society organizations and business groups as well as donors and government officials.

To date, while $74.4 million has been pledged or contributed to the fund by international donors, according to World Bank officials, only $5 million has actually been disbursed, to Kafalat, the financial company implementing the small business grant program.

Apart from the small business grant program launched last month, World Bank officials said three other projects are in the works to be funded by the facility, with two of them — one aimed at restoring heritage buildings and one at supporting the “social recovery needs” of vulnerable groups impacted by the blast — projected to launch in early 2022.

Outside of the financing facility, another $29.7 million had been disbursed directly by donor countries to projects falling under the priority areas defined in the 3RF in the first nine months of 2021, according to a report compiled by the United Nations based on donors’ self-reporting.

Unlike the projects to be funded through the World Bank-run facility, those projects were not developed in consultation with the 3RF advisory and oversight groups, and it is unclear to what extent the donors coordinated with each other or with local groups in deciding on the projects — or even what the projects were, as UN officials declined to provide a detailed list, stating that the data was still preliminary.

However, a UN source provided examples of some of the projects on the list, including rehabilitating schools and hospitals damaged by the blast and providing legal assistance to the victims; but also including some initiatives not directly or solely related to the explosion, such as expanding the government’s National Poverty Targeting Program and taking steps towards implementing the Emergency Social Safety Net cash assistance program.

In either case, the total falls far short of the $426 million that had been identified as needed to cover short-term recovery needs in the first year of the program.

“The funding reported by donor partners and implementing partners do not fully represent the international support to Lebanon under this framework,” the source said. “We will continue to follow up with donors and partners to provide a more comprehensive overview in the next quarter.”

Delays in funding and implementation

In July, the independent oversight board of the 3RF issued a statement complaining of “limited cooperation” by the Lebanese government to facilitate recovery projects. For instance, the group noted that the Finance Ministry “has suspended the signature of a non-objection letter thereby blocking for five months a $7 million transfer from the World Bank to Kafalat, the entity tasked with activating a 25 MN USD flagship project meant to provide support for struggling businesses.”

Mouna Couzi, the World Bank’s head of Lebanon operations, told L’Orient Today, “It’s a legal requirement for the World Bank to receive a no-objection letter from the Ministry of Finance providing the go-ahead to proceed with the proposed project. It’s a lengthy process because a legal opinion is required from the Ministry of Justice for project appraisal, negotiations and ultimately Bank approval ... So it’s the usual delays in government procedures that slightly delayed getting this letter.”

Jha was blunter.

“I think in the case of 3RF projects, particularly those financed by the [financing facility], there have been, I would say, unacceptable delays in receiving clearances [from the government],” he said. “It’s been more than a year … I would hope that the government would make it a priority to focus on rebuilding after the port explosion disaster. In a real sense of the term, rebuilding hasn't started yet.”

A Finance Ministry spokesperson declined to comment on the reasons behind the holdup in issuing the letter.

Samir Daher, economic advisor to Prime Minister Najib Mikati, said he could not comment on the actions of the previous caretaker government, but that Mikati’s government, which took the reins in September, is trying to facilitate the work of the 3RF, including by designating staff in the prime minister’s office to coordinate with the international institutions working on the framework.

“It is important. This is a program, this is a framework that's in line with our program of economic and institutional reforms,” he said.

Some involved in the project said Mikati’s government has indeed taken a more active role in facilitating the 3RF projects than the previous government of Hassan Diab.

Nevertheless, donors have been reluctant to give more money until they see results on the ground.

“We expect more pledges from donors when they start seeing results of projects under implementation,” Couzi said.

Likewise, some had been reluctant to give amid a yearlong government vacuum post-explosion during which political parties were wrangling over the makeup of the new cabinet and most major decisions about the direction of the country were on hold.

Jaap van Diggele, coordinating officer of the 3RF Secretariat, told L’Orient Today, “There are many projects with allocated funding on hold, because we are waiting for the reforms to happen.”

He added, “The problem in the past decades was not the lack of funding; the problem was the way this funding was spent.”

Whatever the reason for the delays, however, local analysts agreed that they are harming the people who most need the help.

“When you take too long to agree and move forward on designed interventions, by the time the [projects] are coming through, the validity, and the effectiveness and potential for impact of those interventions, is, as a result dramatically decreased,” said Lynn Zovighian, co-founder and managing director of The Zovighian Partnership, a social investment platform that manages and monitors humanitarian funding and philanthropic interventions in Lebanon and the Middle East, and who has reviewed the 3RF operations. She noted that the economic situation in Lebanon has significantly deteriorated since the port explosion.

Likewise, Asmahan Zein, a partner in Filovault Crypta Sal, advisor to the board of the Lebanese League for Women in Business and co-chair of the consultative group for the 3RF, said that during the year and a half since the blast, in the absence of meaningful assistance to affected businesses, “many [businesses] closed and went abroad.”

“We're losing a lot because of those delays,” she said. “Even people, they lose motivation, because you keep promising and you are not able to execute, to meet the promises.”

A new approach?

It is not uncommon for the international community to launch a so-called “country platform” to coordinate aid in the aftermath of war or natural disaster. But the 3RF’s approach was new, at least in the Lebanese context, in giving a seat at the table to local NGOs and other interest groups as well as international players and the government.

“I don't think civil society organizations were ever that involved in the making up of an urban policy of recovery in the history of Lebanon,” said Mona Harb, a professor of urban studies and politics at the American University of Beirut and co-director at Beirut Urban Lab, who sits on the 3RF's consultative group. “We've never had such primary, prime seats at the table.”

As for how that has played out in practice, she said, “I would say it's a quite a mixed bag of achievements and incompleteness, very much also related to the fact that we didn't have a government until recently, and then it got paralyzed again,” in reference to Mikati’s cabinet failure to meet since Oct. 12 amid a standoff between political factions over the fate of port blast investigation lead Judge Tarek Bitar.

Despite the stated purpose of channeling funds through institutions other than the Lebanese state, Harb noted, the success of the framework is “very much contingent on the effectiveness and efficiency of state institutions and their proper functioning, even if it wants to distance itself from [the government].”

Zein agreed: “When you don't have a public sector, you don't have a country. So let us not ignore that. We cannot replace the public sector.”

Some others criticized the lack of direct involvement for residents and business owners in the damaged neighborhoods.

Christina Bou Rouphael, researcher and community coordinator with Public Works Studio, which has been advocating for residents of the affected neighborhoods, told L’Orient Today, “The main concern about it is that the residents and the victims are not represented in this framework, so their perspectives may not be taken into consideration.”

She added, “If you ask any resident or anyone in the area, there is a high chance that they don’t know what the 3RF is.”

That was the case for Diab, who has nearly given up on the prospect of getting help to reopen his shop.

On Monday, he said, an NGO worker contacted him after spotting the sign on the door of his now-shuttered old storefront directing customers to call him to get directions to his new location. She wanted to see if he might be eligible for assistance. But upon finding out that he was now working out of his home, Diab said, she told him he would not be eligible.

Before the explosion, he said, “We were living well and we didn’t need NGOs or anyone else. If we had a store, we wouldn’t need help from anyone.”

This article was produced in partnership with the Samir Kassir Foundation.