Badia Masabni as an odalisque, photo taken from the Arab Week magazine. Cairo, 1960. Beirut, Abboudi Bou Jawde collection. (Credit: Abboudi Bou Jawde photo via the Arab World Institute)

In L’Orient-Le Jour’s series, “'Unknown Women Who Shook Up the Arab World,” we delve into the life of Badia Masabni, who is of Lebanese-Syrian origins, founded in 1929 the famous Casino Masabni, which turned into one of Cairo’s main venues for social and cultural events between World War I and World War II.

With her gray hair up in a bun, chest up and a proud look, at the age of 74 — approaching 75 — Masabni was a living legend. From the interwar period to the 1950s, she saw in her casino in Cairo, the greatest names, including Farid al-Atrash, Naguib Mahfouz and King Farouk.

In 1966, when a young Laila Rustom timidly asked her on a television set whether she is married, the star did not bat an eyelid. “Not at the moment. I live alone,” she replied.

Known as the “dean of belly dancing,” the “mistress of theater,” or the “queen of the night,” the Damascene dancer represents a world in itself: the magnetism of Arab capitals, the hubs of the region’s cultural movement in the first part of the 20th century, the advent of cinema, and the air of freedom, which authoritarian regimes in the region were quick to sweep away.

After half a century, the memory of this fantasy world and the stereotypical image of the belly dancer are still there. But the name of Badia Masabni has almost entirely disappeared.

Even when evoking the golden age of the sharqi dancing, other younger, more famous, more glamorous dancers are often mentioned before her. Samia Gamal, Tahiya Carioca, Naima Akef or Nagwa Fouad: for the general public, they are the real legends.

However, most of these “belly-dancing divas” went to the dance academy Masabni had founded in 1929 in Cairo. She is the one who taught them to take the stage and to become comfortable with the camera like an actress. It is also her who encouraged them to challenge the classical codes of the “baladi” dancing by daring to mix genres, add some creativity and own their bodies.

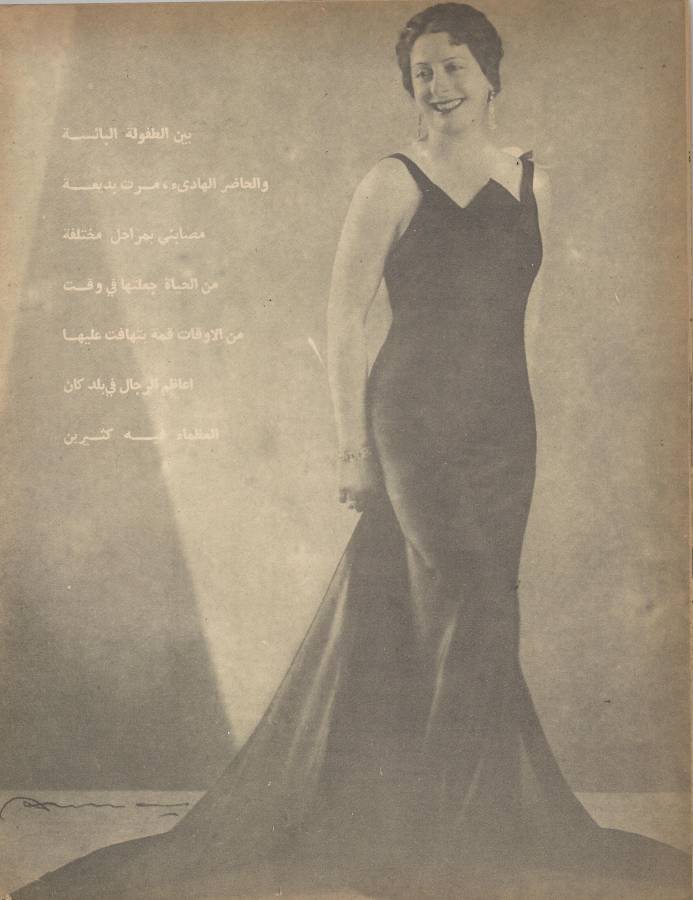

Badia Masabni in evening dress, photo taken from the Arab Week magazine. Cairo, 1960. Beirut, Abboudi Bou Jawde collection. (Credit: Abboudi Bou Jawde photo via the Arab World Institute)

Badia Masabni in evening dress, photo taken from the Arab Week magazine. Cairo, 1960. Beirut, Abboudi Bou Jawde collection. (Credit: Abboudi Bou Jawde photo via the Arab World Institute)

Masabni, a polyglot artist with multiple talents — a dancer, singer, musician and actress — and an influential woman, characterized as fascinating and renowned for her intelligence, contributed to shaping the entertainment industry by fostering a new culture of entertainment for the region.

With “raqsa Badia” (Badia’s dancing), she brought about a belly dancing revolution by modernizing it — and claiming it.

“She presented herself as one of the first dancers to have dared to mix Arabic and Latin music,” said Mariem Guellouz, a dancer, researcher and lecturer at the Université Paris-Cité.

The queen of the dance

She was by no means, or almost by no means, predestined for this royal destiny. The tragic beginnings, in Damascus at the end of the nineteenth century, of the youngest of eight siblings were far from the flamboyant dancing cabaret world.

Born in 1892 to a Lebanese mother and a Syrian father — a soap factory owner who died a few years after her birth — Wadiha, her real name, was raped at the age of seven. But her journey rapidly took a completely different course.

It all began when her father died and she moved with her mother to Buenos Aires, where she spent nearly eight years. The young girl immersed herself with local influences. Jazz, Latin rhythms, rumba: her universe was enriched with new references, which she took with her once she returned to her native region.

“During her late childhood and preadolescence, she accumulated knowledge, and learned different dances, different music, different languages,” said Guellouz.

These adventures she had on the other side of the Atlantic helped her keep an open mind and develop a curiosity that distinguished her — creating the basis of her artistic and commercial approach at a later stage.

Badia Masabni, photo taken from the Al-Ithnayn wal dunya magazine. Cairo, 1938. Beirut, Abboudi Bou Jawde collection. (Credit: Abboudi Bou Jawde photo via the Arab World Institute)

Badia Masabni, photo taken from the Al-Ithnayn wal dunya magazine. Cairo, 1938. Beirut, Abboudi Bou Jawde collection. (Credit: Abboudi Bou Jawde photo via the Arab World Institute)

When she returned to the Middle East, the young woman settled in Beirut before heading to Cairo.

Newly married to Egyptian actor Naguib el-Rihani, she discovered the vibrant life there. The Egyptian capital is already a cultural hub and a regional capital for music, theater, literature, and the cinema, which was new back then.

In the small inner circles that she visited regularly, the biggest names in the Arab scene were joined by authors, international stars and European visitors.

Casino Badia, which she set up in Place de l'Opéra, in the heart of the city, blended perfectly with this prevailing multiculturalism, which was avant-garde, festive and exclusive at the same time.

“It was a place with an entra reserved for an elite that can afford to eat and drink outside. It was also a place considered as a meeting place between men and women writers, artists, intellectuals,” said Guellouz.

It was like a music hall, where people go to eat, to watch a show, or simply to socialize. In a few years, she built a small kingdom in the heart of Cairo, until she became “the unparalleled queen of dancing and entertainment,” wrote Hajer Ben Boubaker, historian and independent researcher, in an article published on the online site of the Arab World Institute.

Business model

The rapid success of Casino Badia is actually based on a business model that leaves nothing to chance. Masabni is certainly an artist, but the young woman had a head for business and “a particularly developed innovative spirit,” said Guellouz.

This is the secret of “Badia’s ingenuity.” On stage, she does everything to satisfy the customer to have him come back. “She wanted to modernize dance, but with the aim of offering the public something new,” she added.

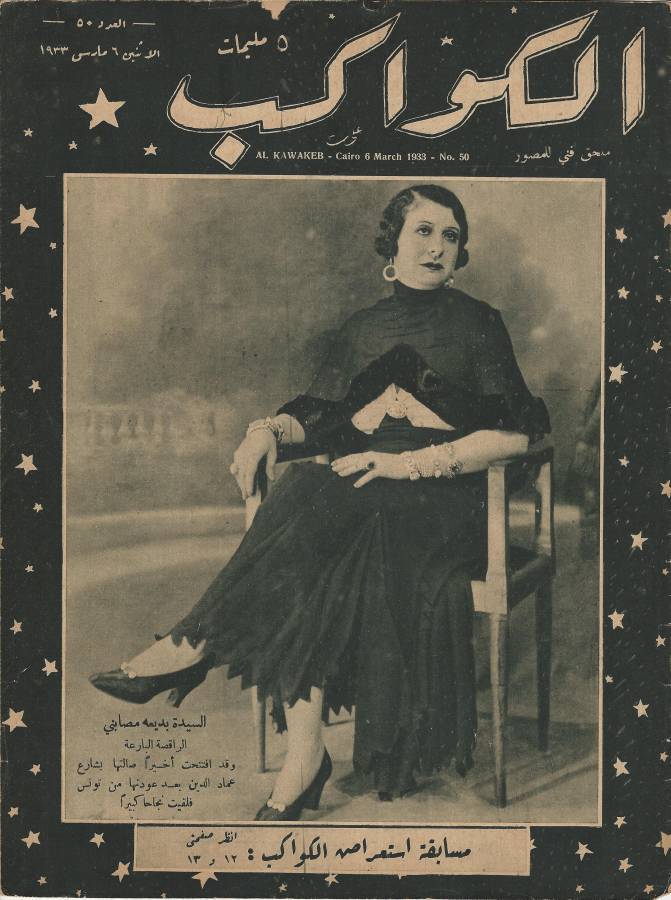

Badia Masabni, the Al-Kawakeb magazine cover. Cairo, 1933. Beirut, Abboudi Bou Jawde collection. (Credit: Abboudi Bou Jawde photo via the Arab World Institute)

Badia Masabni, the Al-Kawakeb magazine cover. Cairo, 1933. Beirut, Abboudi Bou Jawde collection. (Credit: Abboudi Bou Jawde photo via the Arab World Institute)

The way Masabni performed on stage as a real show was unprecedented. While traditional dancers usually remain in a fixed point, Masabni’s troupes moved across the entire stage.

The movements were more liberated, arms placed above the head, new musical instruments were introduced and some steps were borrowed from other dances, such as French cancan, ballet or jazz.

Jewelry, rhinestones, transparent veils and nude outfits were part of the show. Everything, from choreography to the costumes, from the gestures to the music, was studied in detail in order to integrate the baladi heritage into external influences, the techniques of that time into those of the past. The objective was to surprise the audience.

This freedom of tone was not entirely new — but Masabni went further by making this porosity a trademark, by “thinking of this mixture and claiming it,” said Guellouz.

She turned the female body into an instrument and source of creation capable of reinventing itself with each performance. By integrating a dance academy into her casino, she extended her influence to a whole new generation of dancers.

“The women who came to her knew how to dance, but she taught them how to go on stage, to choreograph a dance, and attract the public,” said Guellouz.

Her acting roles on screen further shaped her status as “the ambassador of belly dancing.” In The Queen of the Stages (directed by Mario Volpe, 1936) or Cairo Nights (directed by Ibrahim Lama, 1940), she was among the first to facilitate the widespread use of sharqi across Arab cinema.

In more ways than one, Masabni's incredible journey looks like something out of a Hollywood movie. And yet the end of her life, much less grandiose, resembled a blockbuster that faded.

Masabni, Damascene by birth, led a comfortable life until the end. But during her later years, she became more discreet and gradually withdrew from the arts scene.

She died at the age of 82, away from the crazy Egyptian nights, at the foothills of Mount Sannine in Zahle, Lebanon.

Could this be the reason her name has been partly erased from collective memory? It is difficult to tell.

One thing is sure, while “no dancer is saying today that she/he is performing Badia’s dance” said Guellouz, her soul was instilled in generations of dancers after her.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour.