Passengers of the SS Frossoula posing in group photo with the ship's life buoy. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

BEIRUT — As Lebanon has spiraled into crisis over the past three years, an increasing number of people have departed by sea, land and air in search of refuge in Europe, sometimes with tragic results. But some 80 years ago, the roles were reversed: Lebanon became an unlikely haven for Jewish refugees fleeing Europe, as wealthier and more powerful countries, including the United States, slammed the door in their faces.

It’s a history that few remember, despite the echoes of that moment today. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered the largest wave of displacement in Europe since World War II, with some 4 million Ukrainians having fled to neighboring countries in the first five weeks of the conflict.

Those refugees have received a warmer welcome from host countries than have people fleeing many past conflicts — including those who fled Europe after the rise of the Nazis.

After Nazi Germany’s annexation of the German-speaking Sudetenland region in Czechoslovakia and the wave of violent pogroms against Jews known as Kristallnacht in 1938, fear heightened and migration accelerated. Many Jews boarded ships to leave.

There was a strong current of anti-refugee sentiment in many of the potential countries of asylum, and many refugee ships faced closed borders. One such case, now infamous, was the SS St. Louis, which set sail from Hamburg, Germany in May 1939 carrying 900 Jewish refugees.

The ship was turned away from every port at which it attempted to dock — Havana, Cuba; Miami, Florida; and Halifax, Nova Scotia — and so was forced to sail back to Europe, where 250 of its passengers subsequently died in the Holocaust.

Some other ships were more fortunate, such as the SS Frossoula, whose passengers found safety in Beirut.

Marta Steiner on board the ship preparing a meal with other women. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

Marta Steiner on board the ship preparing a meal with other women. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

Turned away at sea

In late March 1939, Romania’s Black Sea-Danube port of Sulina saw 650 refugees, most of them Jewish — among them doctors, lawyers and soldiers from countries including Austria, Czechoslovakia and Germany — cram themselves aboard the SS Frossoula, a 1,282 ton cargo boat built to hold only 200 people.

The passengers included former Czechoslovak army officers and ordinary soldiers, some still in their uniforms, which were their only possessions. They had been sent to concentration camps after Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia on Oct. 10, 1938 but had managed to escape the country.

The Frossoula was a Panamanian-registered Greek ship initially headed for Shanghai; during World War II, China accepted 20,000 Jewish refugees from Europe.

Among those on board was 27-year-old Marta Steiner from Prague. Before leaving Europe, she was a model and actress. As Hitler began to conquer parts of Czechoslovakia, Steiner and her family decided it was time to leave for good, selling all of their belongings in 1938; they also helped other people register to join the voyage, including relatives and friends who had been undecided about leaving.

“A threatening dragon was about to swallow us,” she would later tell school children, the Acorn newspaper reported.

After Hitler took Prague in 1939, the family went to Vienna first, then traveled down the Danube to Sulina.

Photos taken by Steiner’s then-boyfriend, Alfred Loebl, show her along with other passengers in the early days of the voyage, looking relatively carefree. There were even shots of a wedding ceremony onboard.

The ship ran into trouble as it crossed into the Mediterranean. Food and water supplies were low and some of the passengers were suffering from scurvy. The presence of rats on board the vessel reportedly ignited an outbreak of plague, although the historic record is unclear on exactly what disease spread among the passengers and crew.

A British parliamentary report described conditions on the ship as “without any sanitary accommodation whatever, without any fresh water for washing, the sort of place in which no civilized Government would ever put prisoners.” The Philadelphia weekly Jewish Exponent described the travelers as the “legion of the damned.”

Refused entry at several ports, the ship wandered at sea for 11 weeks.

The Frossoula’s passengers were not alone in being denied docking rights. According to a dispatch from the American Consul in Jerusalem, by July 1939 there were at least four ships roaming the Eastern Mediterranean with 2,550 Jewish refugees on board. Each ship was refused admission at multiple ports. One of them, the SS Rim, carrying 400 passengers, caught fire and sank on July 6. The survivors were picked up by the Italian Coast Guard and taken to the island of Rhodes.

Wedding on board the SS Frossoula. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

Wedding on board the SS Frossoula. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

Quarantining in Beirut

On the same day, the Frossoula entered Lebanon’s waters, at the time administered as a French Mandate. But it would be 10 days before its passengers were allowed to disembark. The ship first reached the port of Tripoli but was not allowed to land. It then made its way to Beirut, with the captain wiring the port authorities that a plague had broken out on board and that the passengers and crew needed medical care. Again, they were refused entry.

But the refugees did have advocates behind the scenes. As the captain pleaded with the port to let them land, a Scottish Quaker missionary and high school principal named Daniel Oliver got word of what was happening and traveled from Brummana to Beirut — a long road at the time — to try to persuade the French High Commissioner to allow the ship to dock until another suitable arrangement could be found and to provide urgent medical care to the passengers in the interim. Oliver told the Manchester Guardian that the ship was only allowed to land as “an exceptional favour” until it was fumigated.

What soon unfolded is detailed in a letter dated Aug. 10, 1939, written by Oliver’s wife Emily and shared with L’Orient Today by their great-granddaughter, Kim Brengle: “Beyrout was the only place where they [the passengers] have received any kindness & been allowed to land, tho’ only in the quarantine station where the accommodation is naturally very simple but clean & it must have seemed like Heaven to these poor refugees after all they have suffered.”

She added that the quarantined passengers “have good simple food given to them & fresh water & to breathe pure fresh air again must have been almost the greatest [benefit] of all.”

At the time, Beirut’s Quarantine (today’s Karantina) was well equipped for this kind of traffic. The Mandate had refurbished it in the late 1920s to function as a center to isolate and vaccinate Muslim pilgrims before they headed on to Mecca.

Photo of refugees inside the Beirut quarantine in today's Karantina. (Source: l'Univers Israelite. Photo courtesy of Mike Azar)

Photo of refugees inside the Beirut quarantine in today's Karantina. (Source: l'Univers Israelite. Photo courtesy of Mike Azar)

Soon other ships followed. The SS Osiris, carrying 600 refugees from Hamburg, was also denied entry at Tripoli port. The captain radioed that he had been searching for a landing place for several weeks. The ship's food was exhausted, he said, and he refused to leave until they were allowed to land. The Osiris was eventually allowed to enter Beirut after an inspection found that its passengers needed medical care. This brought the total number of Jewish refugees in the city to almost 1,250.

Another ship, the SS Thessaly, was not allowed to dock because inspectors found no disease amongst its 800 passengers. The ship’s fate is unknown.

For the refugees who were allowed to land, the quarantine arrangements resembled a field kitchen, with tents for accomodation. Of the passengers who were housed there as of July 28, 27 were in the hospital, with two in critical condition, while two had committed suicide.

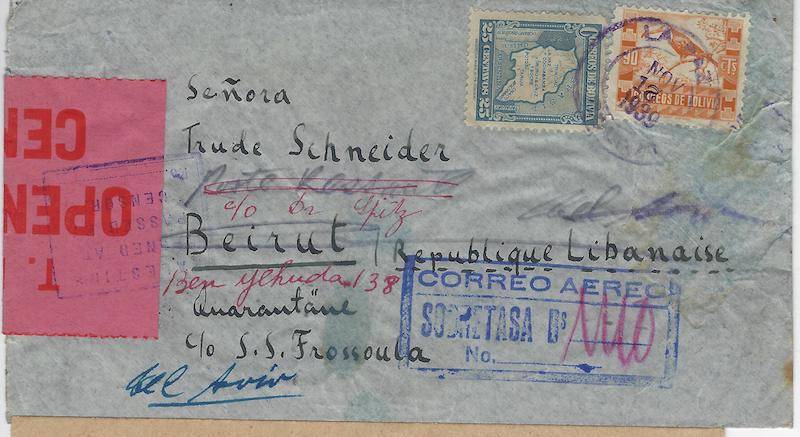

Letter sent from Prague is addressed to the SS Frossoula. Notice the word "quarantined" on the left.

Letter sent from Prague is addressed to the SS Frossoula. Notice the word "quarantined" on the left.

According to the memoir of American engineer Walter Lowdermilk, who visited the quarantine, the refugees were malnourished and most had scurvy. He described what he saw as “one of the most tragic spectacles of modern times,” adding that it was a “stigma upon our modern civilization!”

Emily Oliver noted in her letter that the refugees had “paid good money for decent accommodation & been swindled at every turn & corner.” The High Commissioner’s report indicated that they had paid $1,000 each for passage. “The price was exorbitant, but nobody cared,” Steiner recalled in an interview.

The residents of the quarantine weren’t completely disconnected from the world; during their five week stay they received letters addressed to the quarantine from Europe.

One unnamed observer working for The Palestine Post, who was permitted to enter the quarantine, found the passengers playing games to pass the time. He noted that though the refugees were well fed and living in adequate accommodations compared to where they had been before, they nonetheless had “nothing to do but to speculate about their future.”

Local support & opposition

Their fate was up in the air, as it was doubtful they could make the trip to Shanghai, for reasons including their poor health, the possibility of the second World War breaking out at any moment, and political wrangling between the French and British over where to resettle them. Authorities in Lebanon were debating what to do with them, whether to allow them to stay, send them back to sea or resettle them in another location such as Palestine or Cyprus. A number of refugees had relatives in Palestine and wanted to join them.

The local Jewish community had raised 12,000 francs to pay for the refugees’ accommodations, and contributions were also made by Christian and Muslim residents of Beirut. However, some animosity still lingered over their presence.

In a July 26, 1939, issue of the Lebanese newspaper Le Jour, the Jewish Community Council, the religious authority for Jews in Lebanon, published an open letter responding to a story in the magazine La Bourse Egyptienne, which had alleged that the refugees were not being properly quarantined and called on the local Jewish community to stop aiding them lest they might want to settle in Lebanon. In response, the council wrote that the refugees were confined to the quarantine area, were only in Lebanon temporarily, and that the council was not responsible for determining their fate.

The local debate was not a new one. When Hitler came to power in 1933, many had raised the question of whether Jews would be given asylum in Beirut as the Armenians had been before. The proposition received mixed reviews.

As early as 1935, The New York Times reported that the French mandate officials showed some interest in admitting Jewish refugees as long as they were able “to bring the country new forms of activity” in the form of capital or expert knowledge and as long as they would not compete with local artisans. According to an article by Guy Bracha published in the Leo Baeck Institute Year Book journal, many who had an eye for business were in favor of the capital Jewish refugees could bring. Others were wary and saw their potential arrival as part of an attempt to settle non-Arabs in the region.

The same issues surfaced with the arrival of the boats in 1939. Soon after landing the question of the passengers’ fate made headlines around the world.

In a column published July 20, 1939, in Le Jour entitled “Wandering Jews,” columnist Khalil Gemayel asserted that settling the refugees in Lebanon was “out of the question” for the moment, as Lebanon had already settled Orthodox refugees from Syria after Turkey annexed the Sanjak of Alexandretta (Iskenderun). He suggested that a solution should be found for them elsewhere, possibly Africa.

Photo taken from the SS Frossoula as it neared the port of Beirut. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

Photo taken from the SS Frossoula as it neared the port of Beirut. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

However, according to the Jewish Telegraph Agency, the refugees asked to remain in Lebanon or Syria, although it did not explain why.

Well-wishers launched campaigns to secure them a safe haven. Among them was Daniel Oliver, who wrote in an Aug. 9 letter to the Manchester Guardian that “everything is being done to prevent them from going back to sea. But a secure location needs to be found for them.”

The plight of the refugees made it as far as the British House of Commons, with MPs Eleanor Rathbone and Josiah Wedgwood championing the refugees’ cause.

“Something must be done,” Rathbone said in a statement on Aug. 4, as “the country from which these refugees come is one to which [the] government has acknowledged particular obligations.”

“I beg the Noble Lord to deal with this problem,” she said, addressing the government’s representative in parliament, “whether it be by allowing these poor people into Palestine or allowing them into Cyprus [both countries were under British control at the time].

“Do not let us leave them forever to the French,” Wedgwood added, “or to the alternative of starvation.”

In the end, the British government refused to accept responsibility for the refugees.

Palestine was off limits. In the wake of growing tensions between Zionists and Palestinian nationalists and Palestine’s 1936-39 uprising, coming on the heels of a large influx of Jewish immigrants in the 1930s, the UK had instituted a new quota system under the White Paper of 1939, which restricted Jewish migration to Palestine.

Meanwhile, the French authorities overseeing Lebanon insisted on sending the refugees back to sea, but the crew had deserted, and the captain refused to set sail.

The expulsion was delayed due to a crime that had taken place on the ship. As Emily Oliver recounted it, one crew member had murdered another at the port of Beirut. This, she noted in her letter dated Aug. 10, 1939, “gave time for [the refugees’] friends to try & help them & we have just heard that they are to be allowed to enter Palestine — on next year’s quota as the present year’s has already been exceeded.”

A turning point

A short-term solution appeared on Aug. 29, 1939, when the S.S. Tiger Hill sailed into Beirut from the same Black Sea port as the Frossoula with 800 Jewish refugees on board. After docking it took on passengers from the Frossoula and sailed to Palestine. Among them was Marta Steiner, who recalled that the captain had to beach the ship because the British had denied it docking rights.

Today Jewish migration to the region is seen through the prism of the post-1948 occupation of Palestine but, according to Yair Wallach, a professor at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies who has studied Ashkenazi Jewish migration to the Levant in the pre-Nakba period, “the overall majority [of Jewish migrants at the time] were not Zionist.”

“Today if we talked about them we would have seen them as refugees, and as refugees it is not surprising that they wanted to go to Palestine,” he said, noting that some of the refugees went to join the British army to fight against the Germans. He also noted that, of the other countries of refuge in the region, “in Egypt, they were more likely to stay because there was a bigger Ashkenazi scene there, which in Lebanon there wasn’t.”

The children of the SS Frossoula. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

The children of the SS Frossoula. (Photo by Alfred Loebl)

Once the United Kingdom joined the Second World War on Sept. 1, 1939, immigration policy was relaxed to allow Jewish refugees to fight on the British side and to strengthen Palestine’s defense forces, which at the time included Arab, Jewish and British soldiers. The 150 Jewish former officers and 175 privates from the Czech army who had been quarantined in Beirut were brought to Palestine to work with a group of chemical warfare specialists.

Speaking to L’Orient Today, Joshua Donovon, a PhD candidate at Columbia University, said this recruitment into the British army in Palestine was “part of a longer history of empires instrumentalizing populations that they have control over for the purposes of war.”

The fate of the other ship docked in Beirut at that time is unclear, but a number of the refugees stayed in Lebanon past 1939. Some volunteered to join the Turkish army to fight Hitler after a meeting held in Beirut in 1940.

Afterward, Beirut became something of a transit point for Jewish refugees. On Dece. 19, 1939, The Palestine Post reported that 120 Jewish refugees who had arrived in Beirut took the road to Jaffa. Later on March 6, 1940, 84 passengers, among them 25 children, landed in Beirut and went on to Haifa by car.

There were also some instances in which Jewish orphans were smuggled out of Denmark after the Germans invaded in 1940 and taken first to Beirut via Marseille, then smuggled to Palestine.

Within Lebanon, the political situation shifted dramatically after the fall of Paris to the Germans in June 1940. With the Nazi-allied Vichy regime now administering the Lebanon Mandate, many Jews in Lebanon felt they were no longer safe.

Feelings of insecurity were exacerbated after a detention camp for the mandate’s European Jews was set up in the mountains. But it was closed after the British and the Free French Army took control of the mandate that same year.

As for the Frossoula, German planes bombed and sank the ship on July 15, 1940, 250 miles off Cape Finisterre in Western Spain, as it was on its way to England. Its 18 crew members boarded two lifeboats but only three survived; the rest, according to Reuters, “were washed overboard [or] died from exposure.”

While the record is unclear about the final destination of all of those Froussoula passengers who found refuge in Beirut, Marta Steiner parted ways with boyfriend photographer, and married a year after arriving in Palestine. In 1946, she and her family moved to the United States where they settled permanently and would go on to have two grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. She passed away in 2019 in the suburbs of Los Angeles, California, two weeks after turning 107.