Children turn into a modern-day street in the Karantina neighborhood. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BEIRUT — On Karantina’s western edge, piles of concrete and debris remain where buildings were mowed down by the shockwave that radiated out from the nearby Port of Beirut one year ago Wednesday, their occupants now dead or displaced.

The rubble is a visible reminder of the most recent disaster to strike Karantina, as the army barriers peppered throughout the neighborhood are visible reminders of past violence, in a place that has been both a refuge for the displaced and dispossessed and a place from which people were displaced and dispossessed.

On real estate maps, there is no such place as Karantina. The popular moniker of the neighborhood in Beirut’s Medawar quarter came from the isolation center for arriving travelers that was built there in the 1830s, among the earliest quarantine stations of the Ottoman Empire.

All vessels bound for what was then greater Syria were ordered to dock in Beirut for quarantine inspection and passengers ferried ashore to undergo their period of confinement.

Beginning in 1915, Armenians fleeing genocide and expelled from their homes came en masse to Lebanon from other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Many of them settled in tin shacks on church-owned land in Karantina, making it one of the world’s first refugee camps.

They settled there in part because of the presence of available swathes of church-owned land, said Diala Lteif, a PhD candidate in urban planning at the University of Toronto whose research has focused on the history of Karantina; and also because of its proximity to Beirut’s train station, built in 1895, and to the port, where many of the refugees first arrived.

Later, there would be more waves of Armenian migration, an influx of Palestinian refugees after the 1948 Nakba, Syrian and Kurdish migrant workers, and Lebanese Shia families coming from the south — among them, the family of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, who grew up in Karantina’s Sharshabouk camp in a small tin house like the ones inhabited by the Armenian refugees.

“It’s this interesting place where all these people who kind of blur the categories and blur the boundaries between the categories coexisted,” Lteif said.

Since its inception, Karantina also has “a long history of marginalization,” Lteif said. “It is the place where we dump everything we don’t want, be it the garbage plant, be it the slaughterhouse, be it the travelers. It’s the place where we put the problems we don't want to deal with.”

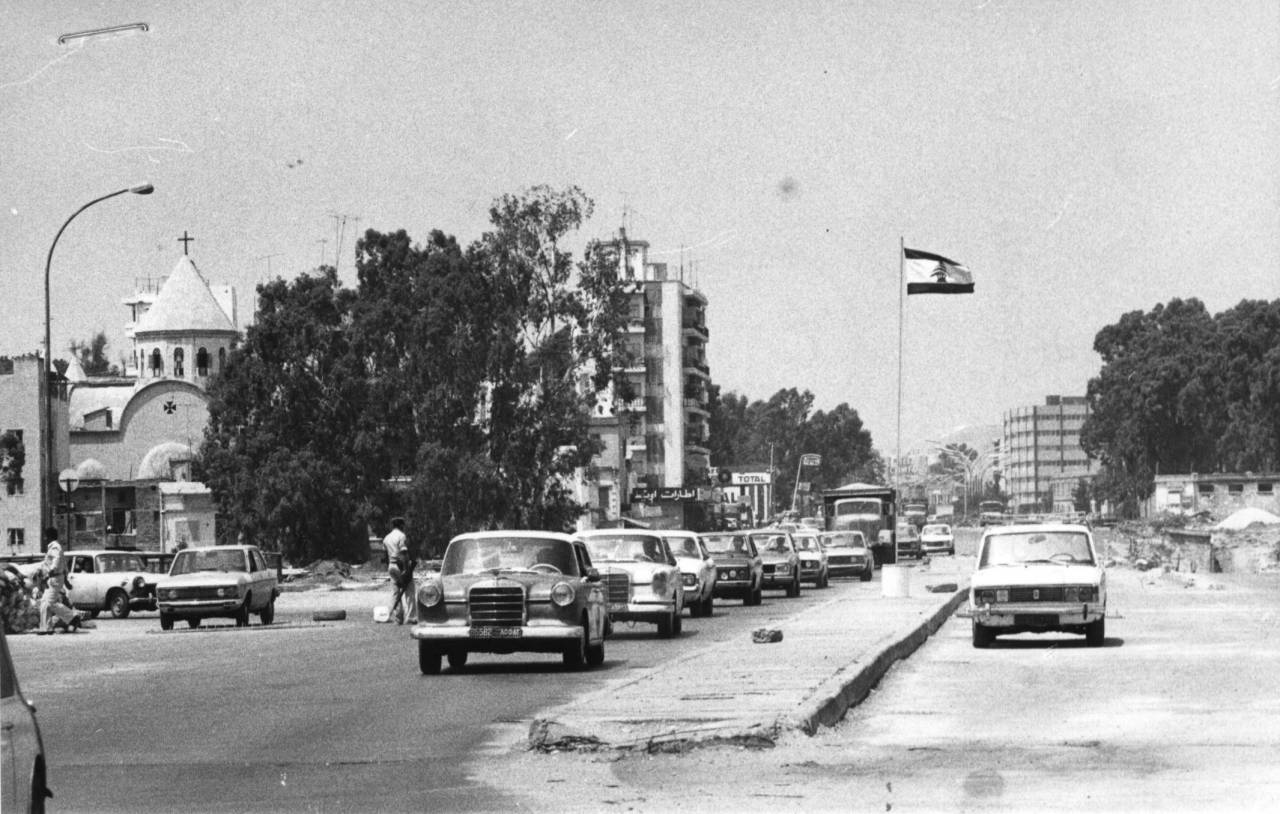

A Karantina streetscape in 1978. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archive)

A Karantina streetscape in 1978. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archive)

Salem Khalaf was born in Karantina in 1960, the same year as Nasrallah, and grew up there but not in a tin house.

“My father was rich before the war,” Khalaf told L’Orient Today. “He owned many small buildings, and he was a merchant, but now I am a poor man. The war came, and there was no future.”

In Khalaf’s boyhood, Karantina, despite its marginality, was still somehow idyllic. The port of Beirut had not yet expanded to cannibalize the coast off Karantina, so Khalaf and the other neighborhood children could go down to swim in the sea.

Although his family were Sunni, descendents of Bedouins who had settled in Karantina around 1900 to work in the slaughterhouse built there in the late Ottoman era, Khalaf went to a Protestant school.

“I think I know the Bible more than you,” he joked to an American evangelical visiting the neighborhood on a recent Sunday, one of a string of do-gooders who have come through the area in the year since the port explosion.

“Karantina was a village, all of us living together,” Jabour Mendelek, a Christian born there in 1950, told L’Orient Today of the prewar years, when his father was a chef in a hotel, Beirut was unironically referred to as the Paris of the Middle East, and the children of Karantina could take the tram to Hamra to go to the cinema. “There were no problems about religion,” Mendelek recalled.

“Everyone is related to each other and our grandparents knew each other,” said Khaled Said, whose father was a livestock trader.

Even between the Lebanese and the migrants and refugees who came from outside, he said, “There was coexistence and familiarity ... and each nationality understood the others and accepted them. And there was also familiarity between the Christians and Muslims. If you saw a group of young guys sitting together, you wouldn’t know who was Muslim and who was Christian.”

Ahmad Moussa was born in Karantina in 1965, to a Palestinian father and a Lebanese mother.

As a child, he said, he felt no difference between himself and the Lebanese children. His father, a meat trader, “would go where he wanted, go and come and no one would ask him, ‘Where is your ID?’” Moussa said.

“It was a normal and really excellent life. Then suddenly, the world changed in 1975, 1976.”

Cars cross the Karantina bridge in 1978. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archive)

Cars cross the Karantina bridge in 1978. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archive)

Moussa refers to the events of January 1976 as a “nakba,” or catastrophe, the same term he uses for the events that pushed his father out of Palestine in 1948.

On Jan. 18, 1976, during the early phase of the country’s 1975-90 Civil War and amid rising tensions between Christians and Palestinian and Muslim enclaves in predominantly Christian East Beirut, the Kataeb and Tigers Christian militias “launched an attack on the Maslakh-Karantina area, bombing it with mortar shells …. On January 19, they raided the area, going from house to house, shooting those who tried to escape,” as the International Center for Transitional Justice reported. Depending on the source, between 600 and 1,500 people were killed.

The center concluded that both the Karantina massacre and the one committed in retaliation afterward in the Christian town of Damour “were systematic and widespread killings that would fit the definition of crimes against humanity.”

Khalaf, then a 15-year-old schoolboy, was captured by the Christian forces as they swept through Karantina. He watched as other prisoners were lined up against a wall and executed, Khalaf told L’Orient Today. It would have been his fate, as well, he said, had it not happened that one of the militia members was a school friend of his and managed to keep him aside from the firing squad.

Instead, he was bused to a detention facility in Achrafieh, where he spent one night before being released in a prisoner exchange after Palestinian and allied forces attacked Damour.

At 16, still a schoolboy, Khalaf said, he joined the Communist Party, which was allied with the Palestinians, as a fighter.

“All of us were brothers, but when the war came, everyone took his group,” Khalaf said. “… I went to the party because they [the Christian militias] took my house, they took my area. I began to fight.”

He added, “I made mistakes, but if you put me in that time again, maybe I will make the same mistakes.”

An older building on the edge of Karantina stands in ruins after the Aug. 4 port explosion. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

An older building on the edge of Karantina stands in ruins after the Aug. 4 port explosion. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Fadi Azar’s Karantina story is nearly the opposite of Khalaf’s, but his, too, ended in displacement.

Azar grew up in the Bekaa valley, and his father was in the army.

“Palestinians came to Lebanon and to the Bekaa, and they came into our house to look for weapons, and they hit my mother,” he told L’Orient Today. “So we had to leave the Bekaa. The army moved us to Beirut, and we stayed in Achrafieh.”

Azar arrived in Karantina in 1978 with the Lebanese Forces Christian militia, which had occupied the neighborhood and set up its wartime headquarters there. Azar said he believed he was protecting Lebanese sovereignty against the Palestinian Liberation Organization and others.

After the war, the Lebanese Forces withdrew from Karantina, handing over their bases to the Lebanese Army. But Azar had married a local girl, so he settled in Karantina and raised his children there.

He stayed until Aug. 4, 2020, when a warehouse full of ammonium nitrate detonated in the Port of Beirut, destroying his house and wounding him and his son.

“I was upset when I left,” Azar told L’Orient Today, “but I was forced to, because the house was gone.” He added that after the explosion, his children no longer wanted to live in Beirut.

He added wistfully, “Living there was really lovely. My children were born and raised down there … but today my daughter tells me, ‘Papa, please don’t pass by Karantina, take a different route.’”

An man stands in Karantina, surveying the damage wrought by the blast. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

An man stands in Karantina, surveying the damage wrought by the blast. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Azar acknowledged that the Muslim residents of Karantina had been forcibly displaced during the war, but said that was simply the nature of conflict.

“As Christians were displaced from some areas, the Muslims were displaced from other areas,” he said. “… After the war, they came back and rebuilt and fixed their houses and we were living there as brothers and neighbors, and there was no problem.”

Indeed, these days, Azar and Khalaf — enemies during the war — are friendly, as are Khalaf and Mendelek, who was with the Kataeb during the conflict and remained in Karantina throughout the war.

“He is a Lebanese Phalangist and I am a Communist, but I don’t want to slaughter him and he doesn’t want to slaughter me,” Khalaf said with a laugh.

Still, he added, “After the war, we trust in the Christians, but not like before, and the Christians trust in us, but not like before.”

In fact, most of those displaced from Karantina in 1976 were not able to return after the war, Lteif noted.

Palestinians and other non-Lebanese citizens were not covered under the Taif Agreement, which outlined the right of the displaced to return to their houses.

And many of the Lebanese who had fled were blocked from rebuilding by bureaucratic issues and the cost of permit fees. Law 322, implemented after the war, gave an exception to building permit fees for displaced homeowners wanting to rebuild their homes in villages and towns — but not in Beirut. Likewise, the law exempted them from certain building regulations, but not in the city.

Because many of the lots in Karantina, like Khalaf’s, were smaller than the minimum buildable lot area under Beirut zoning regulations, their owners could not rebuild. Mona Fawaz, a professor of urban studies and planning at the American University of Beirut, told L’Orient Today that to be able to build on lots below the legal limit, either owners would have to pool their properties together or the city’s zoning regulations, which have been largely unchanged since the 1950s, would have to be amended.

Meanwhile, some property owners found that the Lebanese Army had set up operations on their land, which had previously been occupied by the Christian militias.

“Once order was restored, [the] Lebanese Army took over the militia bases,” Lteif said.

“The militia bases were on private property, and the army just took them over and stayed.”

Said was one of the lucky few who was able to return — his house had not been destroyed nor was the land taken by the army.

“They gave us [funds] for renovations, we fixed our houses and stayed and settled here, and each one started to look for work,” he said.

Khalaf’s family was less fortunate.

“When [the government] said to us to come back, we came here but it was a trick, because they forbid us to rebuild our houses,” he said. His childhood home and his father’s other properties, destroyed in the war, were below the minimum size to rebuild. Today, he lives in his sister and brother-in-law’s house.

As for Moussa, he never returned to live in Karantina, although he comes to visit his relatives who have come back. One of his cousins is now living in the house where he spent his early years.

Although he has fond memories of his childhood in Karantina, Moussa said, “The problem is that sad things always overtake joyful ones. When I go to the area now, I always remember the people who I used to play with and they died there.”

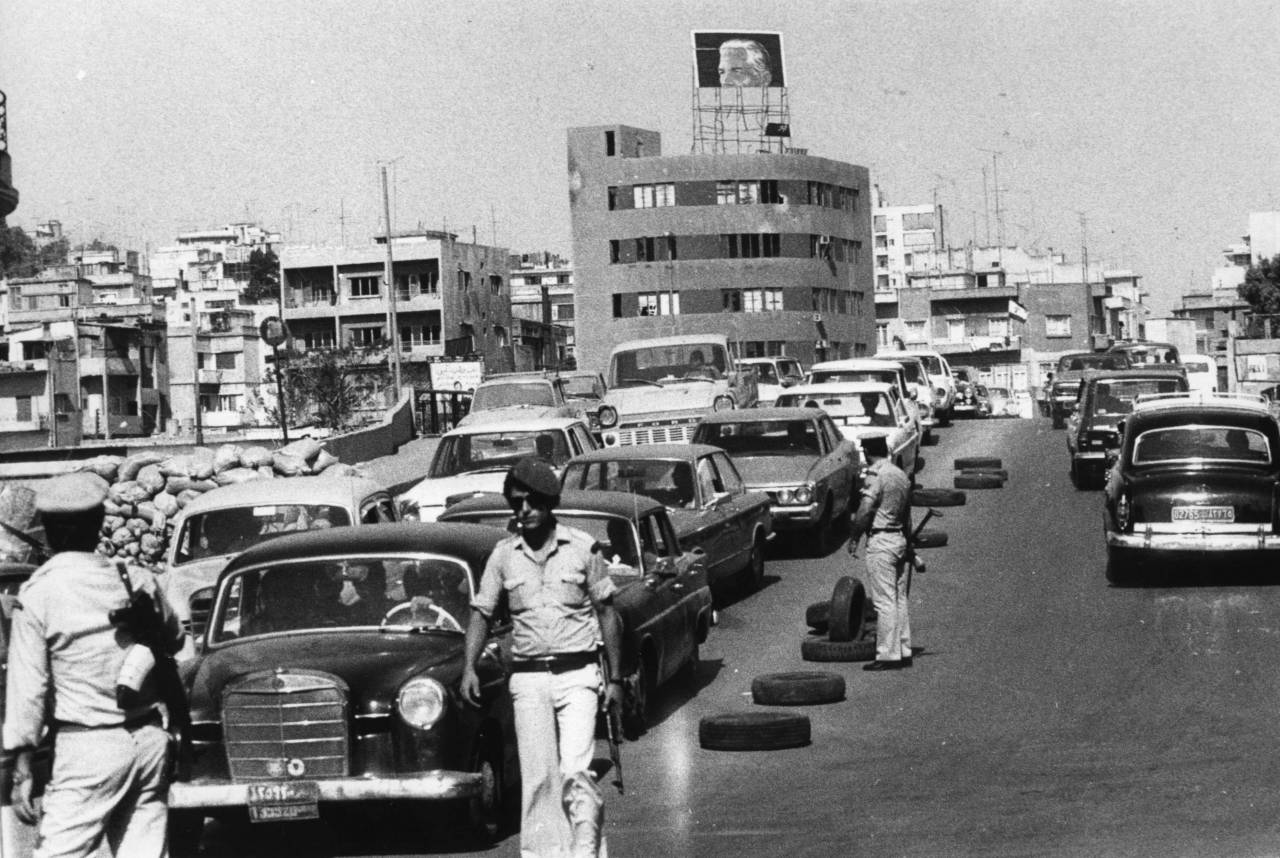

A checkpoint at the Karantina bridge in 1978. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archive)

A checkpoint at the Karantina bridge in 1978. (Credit: L'Orient-Le Jour archive)

Over the years of war, the face of the neighborhood had changed. The old slaughterhouse was closed. The train was no longer running, and the port had expanded so that neighborhood children could no longer walk down to the sea. The area that had previously hosted Armenian and Palestinian refugees would now become home to a new wave of refugees from Syria.

A new, nominally temporary slaughterhouse opened after the war, but it was shut down again in 2014 amid complaints about sanitary conditions and animal cruelty. Despite protests by neighborhood residents and by the displaced — and, in some cases, their children and grandchildren — calling for it to reopen, the facility has remained shuttered.

The closure of the slaughterhouse and the use of sites in Karantina for dumping Beirut’s trash amid the city’s garbage crisis reinforced the impression of many residents that Karantina was the unwanted step-child of the capital. The nightclubs that sprung up in the neighborhood’s industrial areas were not for the area’s residents.

“It’s known that the social class living in the area … is a poor class, all of them are low-level employees, or this one is a fisherman, this one has a corner store,” Azar said. “After the war and the rebuilding of Beirut, the area was treated unjustly. No one paid attention to it.”

When asked whether the municipality plans to reopen the slaughterhouse and what other economic development plans it has for the area, Georges Nour, an advisor to Beirut Gov. Marwan Abboud, said in a statement, “In the current situation of the municipality, the priority action of the Governor is oriented toward the vital needs of the residents of the City of Beirut.”

Nour said Abboud is also planning to create a master plan for the eastern entrance of Beirut, of which Karantina is the core.

“Many ideas are under consideration between all main stakeholders … and therefore any individual action and decisions — besides the fact that [they] cannot be done, for the time being — are simply a loss of money and jeopardize all efforts to think globally for sustainable solutions,” he said.

Ironically, the Beirut port explosion, which wreaked devastation on Karantina, also brought it to the attention of local and international organizations.

Thanks to their intervention, Said told L’Orient Today, “There are people sleeping on the floor [because they don’t have furniture], but thank God, there is a roof and walls and windows.”

Howayda Al-Harithy, a professor of architecture and design at the American University of Beirut, who is heading up a “neighborhood level recovery” project by the Beirut Urban Lab, said the team was pleasantly surprised at how many of Karantina’s residents had chosen to stay or return after the blast.

“The people stayed, and they said they don’t want to leave, because they experienced displacement during the Civil War ... so part of the collective memory is that experience,” she said. “So in this disaster they decided to stay and hold onto their community.”