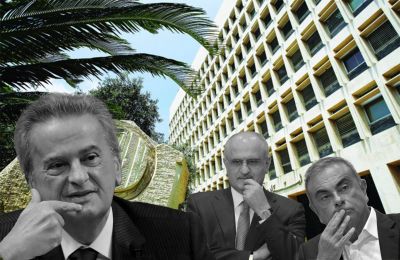

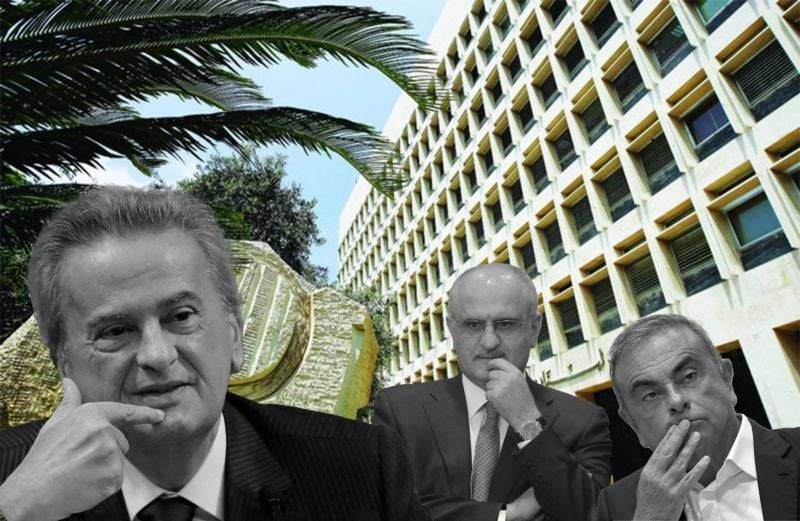

From left to right, Riad Salameh, Ali Hassan Khalil and Carlos Ghosn. (Credit: Photomontage by Guilhem Dorandeu)

He continues to manage, through ad hoc circulars and without any comprehensive financial rescue plan, one of the worst economic crises in modern history. It is a crisis he helped create — he, who has been at the head of the country’s top financial institution for nearly three decades. The situation was already unusual, but since Tuesday, it has become unbelievable. It is like “a local moussalsal [soap opera],” one internet user commented.

On May 16, the day after a hearing that never took place, the French judiciary issued an international arrest warrant against Banque du Liban (BDL) Governor Riad Salameh.

France is one of five European countries investigating this man and his entourage on charges ranging from illicit enrichment to embezzlement and tax evasion.

Based on serious suspicions after Salameh did not show up, the Paris investigating judge, Aude Buresi, confirmed her intention to send a strong signal to the Lebanese authorities.

It has been a mini-earthquake at the country level, and beyond, as the French decision could complicate Salameh travels abroad.

Salameh has announced his intention to appeal the French decision.

While it is likely that a red notice from Interpol will follow the French judge’s decision, it is difficult to anticipate the Lebanese authorities’ reaction — the country has always refused to extradite its nationals.

Caretaker Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi said Tuesday that the governor cannot be arrested or prosecuted in Lebanon without an arrest warrant from Interpol.

Will the issuance of the warrant have the Lebanese authorities cooperate? For the moment, it is impossible to answer this question.

Despite these shadowy areas, the situation remains unprecedented. By attacking a senior Lebanese official, the judge is opening the door to justice.

“Symbolically, this is an important step that shows how serious the facts are in the eyes of French justice,” said Chanez Mensous, advocacy and litigation manager at the French NGO Sherpa, which initiated a complaint against Salameh in France and Luxembourg.

Carlos Ghosn

France’s arrest warrant is a significant step, but it is not entirely unprecedented. Several international arrest warrants have been issued against prominent Lebanese figures.

Following a request from the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, tasked with investigating the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, Interpol issued an international arrest warrant in 2011 against four suspects: Mustafa Badreddin, Salim Ayyash, Assad Sabra and Hussein Anaissi. All of them are members of Hezbollah and none of them has been arrested by Lebanese authorities.

In May 2022, Lebanon received a red notice from Interpol, based on the international arrest warrant issued by France against Carlos Ghosn, the former CEO of Renault-Nissan who sought refuge in Lebanon in December 2019.

On each occasion, the Lebanese judiciary did not cooperate. By refusing to extradite its citizens, it has allowed those wanted to escape prosecution.

“Unfortunately, the country is increasingly adopting a system of impunity where no one is held accountable — this applies to all kinds of serious crimes, starting with the Beirut port explosion in which former minister Youssef Fenianos and current MP Ali Hassan Khalil continue to be free despite the arrest warrants issued against them,” said Nizar Saghieh, lawyer and director of the Legal Agenda.

Several political figures have been implicated in the explosion that killed more than 220 people on Aug. 4, 2020, but the investigation process continues stall due to the numerous requests and lawsuits filed by senior officials prosecuted in the probe.

In Salameh’s case, will the suspect be allowed to remain in office until the end of his term in July?

There are two factors that may help determine the reaction of the authorities. The first is that the case takes place within the more narrow framework of the United Nations Convention against Corruption, to which France and Lebanon are parties.

The latter is theoretically obliged to apply the arrest warrant, if France were to request Interpol to issue a red notice, even if it is “a mechanism whose application is quite flexible, which can resist an opposing political will,” said Mensous.

The second factor to consider is that Interpol has yet to issue a red notice. If it were to do so, the international organization could force Lebanon to make a choice: either comply with international cooperation procedures and hand over the suspect after arresting him on Lebanese soil, or stand at odds with the French judicial authorities.

So far, “the two judicial systems have worked very well together,” said Mensous.

But Lebanon can refuse the request if it wants.

“This touches upon the heart of state sovereignty, namely the physical coercion of a person by virtue of a foreign judicial decision … even if international law provides for such a mechanism, there are many examples where it has not been applied, especially when it comes to nationals,” Mensous explained.

In the long run, however, the country could lose out if it refuses to cooperate. According to Saghieh, “If the attention given to these institutions is deemed insufficient, it could affect political relations with the countries involved.”

By choosing not to cooperate, Lebanon would also confirm its ambiguity vis-à-vis international justice. Beirut, capital of impunity? Nothing new, some may say. “Lebanon is becoming a country where the powerful and the influential can escape the law,” Saghieh added.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.