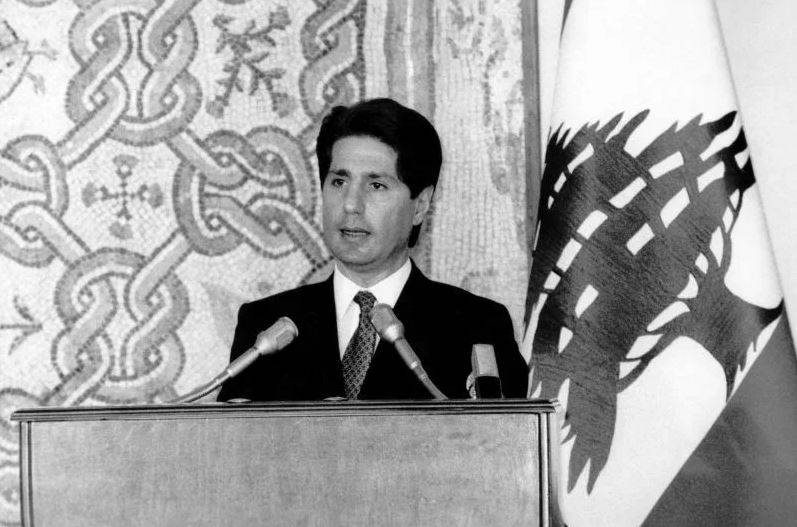

Amine Gemayel giving a speech on Jan. 6, 1984. (OLJ Archives)

On Sept. 16, 1982, Israeli Minister of Defense Ariel Sharon arrived in Bikfaya to offer his condolences to the Gemayel family, two days after the assassination of president-elect Bachir and many of his companions.

Sharon spoke with Pierre, the father of the assassinated president, and his brother, Amin. They both told Sharon that they were sticking to the commitments made by Bachir to the Israelis, which was seen later on as an opening for Israel to green-light Amine’s election as president to succeed his brother. This position was shared by the US envoy for Lebanon, Philip Habib.

Family ties also played a role, as Amine was in a favorable position due to the wave of sympathy with the Gemayel family after the assassination of the young president-elect. This was in addition to a kind of compromise between Syria and the US in order to contain the assassination’s effects and to maintain a semblance of balance in Lebanon.

After his election, Amine Gemayel relied mainly on Washington to deal with the two Syrian and Israeli occupations. Moreover, he was elected at a time when the Multinational Force, including a US contingent, had just finished monitoring the Palestine Liberation Organization’s withdrawal from Lebanon.

From the beginning of his term of office, Gemayel thus committed himself to a logic of total cooperation with Washington. His six-year term was marked initially by the conclusion of the so-called May 17 agreement (in 1983) with Israel, which was supposed to organize the Israeli withdrawal from the Lebanese territory. This agreement was in reality more than a withdrawal agreement, but less than a peace treaty.

It should be recalled that Bachir Gemayel, pressed by Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to conclude such a treaty, was reluctant to do so, as he perceived that such an agreement needed time and preparation. Bachir’s priority, after his election, was first to rebuild national unity after a six year civil war.

Shortly after his accession to the presidency, Amine Gemayel began negotiations with Israel, which first led to an Israeli withdrawal from Beirut to the Awali River, at the gateway to southern Lebanon.

All in all, while the cabinet of Prime Minister Chafic Wazzan and the Parliament endorsed the text, with the backing of the Sunnis’ leader and former Prime Minister Saeb Salam, the president did not sign it.

This is because in parallel to the Israeli withdrawal, the Mountain War between Druze and Christian groups broke out in the Chouf-Aley-Bhamdoun area; a confrontation linked to regional and international balances.

Walid Joumblatt’s Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) considered that the Lebanese Forces (LF) and the Israeli army were working to drive the Druze out of southern Mount Lebanon.

The PSP and its leftist partners, supported by Damascus, went to war against the LF. In September 1983, Christian fighters, fleeing the villages of the region, barricaded themselves in Deir al-Qamar. There, an agreement for their definitive withdrawal from Chouf-Aley-Bhamdoun was reached.

But in many Christian villages abandoned by the militia, massacres against civilians were perpetrated. This war led to an important change in the balance of power, especially after Damascus’ intervention in favor of the left-wing parties, in cooperation with the Soviets.

The Mountain War had repercussions in Beirut, particularly through the 1984 Feb. 6 uprising by Nabih Berri’s Amal Movement and the PSP in West Beirut and Beirut’s southern suburb.

The Christians’ defeat in the Mountain and the Feb. 6 takeover were major setbacks for Gemayel’s six-year term in office, especially as the effects of the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran began to be felt in Lebanon.

In October 1983, concomitant attacks were carried out in the south of Beirut against the US and French contingents of the Multinational Force, which eventually left Lebanon. These attacks were attributed to pro-Iran groups.

Rebalancing

In this context, while cooperation between the Lebanese president and the US administration continued to intensify, Gemayel went to Washington, where he was advised to reopen the channels of communication and coordination with Damascus.

It was in this vein that the March 1984 inter-Lebanese conference took place in Lausanne, organized by Saudi Arabia with the help of the US. Here, Gemayel accepted the idea of a rapprochement with Syria and a de-escalation with his Lebanese adversaries.

He then began a series of political steps, including the appointment of Rachid Karami, who was close to Damascus, to form a cabinet that included Joumblatt and Berri. He also appointed Michel Aoun as new commander in chief of the Lebanese army, succeeding Ibrahim Tannous.

In consultation with his partners, by 1985 Gemayel went so far as to dismiss Parliament Speaker Kamel al-Assaad, a prominent representative of the former Shiite ruling class, who had played a key role in the election of his brother to the presidency.

In addition, there was a tug-of-war between Gemayel and the LF. The president tried to reduce their influence and keep them under his control, particularly in order to facilitate his rapprochement with the Syrian regime.

This mission was accomplished at first, since negotiations began with Damascus. But these talks paved the way for a tripartite agreement concluded in 1985 under the auspices of Syria between the PSP, Amal and the LF, led at the time by Elie Hobeika.

Fearing that he would be overshadowed by Hobeika, Gemayel joined forces with LF military leader Samir Geagea, in an insurrection within the LF against Hobeika.

At the same time, the Amal Movement engaged in a conflict with the Palestinians, a bloody episode known as the “war of the camps,” and then crossed swords with the PSP in West Beirut.

All these factors gradually allowed the Syrian regime to return to the ground in Lebanon, especially from 1987, just a few months before the presidential election. But this return was staved off for a few years.

Syrian President Hafez al-Assad was irritated by Gemayel’s support for Geagea. He reprimanded the Lebanese president for having turned against the tripartite agreement and more generally, for resisting any real stranglehold by Damascus on Lebanon.

In 1988, Syria tried to put forward former President Sleiman Frangieh for a new term in office, but this choice was rejected by the Christians, notably Gemayel, Geagea and Aoun.

The presidential election was therefore blocked when US envoy Richard Murphy went to Beirut and Damascus. The diplomat then proposed his famous equation “Mikhail Daher or chaos,” in reference to the MP for Akkar’s Maronite seat. But this, too, came up against Christian reluctance. A few hours before the end of his term, in September 1988, Gemayel went to Damascus in a bid to find a solution with Assad.

But in Beirut, Geagea and Aoun agreed to block any solution that the two presidents might propose. Gemayel therefore returned empty-handed to Baabda, where forced to improvise so as not to leave the executive helm vacant, he signed a decree appointing Aoun as head of a transitional cabinet.

He did it based on the precedent set by Bechara al-Khoury in 1952 when, before resigning, Khoury entrusted the then-commander in chief of the army Fouad Chehab to lead a cabinet whose mission was to organize the presidential election as soon as possible. The difference between Chehab and Aoun is that the former carried out this task.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Joelle El Khoury.

Sharon spoke with Pierre, the father of the assassinated president, and his brother, Amin. They both told Sharon that they were sticking to the commitments made by Bachir to the...