Beirut Art Center entrance, as seen in late 2022. (Credit: Maria Klenner/L'Orient Today)

BEIRUT — “It takes time to really understand what’s happening on the Beirut scene.”

Reem Shadid pauses to clear her throat. Like many people in town, she’s been working on overcoming a persistent flu. “I came here for a six-month residency at Ashkal Alwan and decided to stay. I’ve been around physically for a year and a half, so of course I’m familiar with a scene but it’s a different challenge when you have a space and specific responsibilities toward people who haven’t left or who chose not to leave” despite more than three years of economic and financial collapse and political inertia.

Shadid has been an energetic actor on the MENA region’s globalized contemporary art scene for almost two decades. A curator, researcher and cultural organizer, she describes her work as engaging with “the emancipatory possibilities within artistic practice, exploring the ways it intersects with ecological, political and socio-economic forms.”

She is currently co-curating the 2023 edition of Taipei Biennial and the 2023 edition of New Visions, the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter triennial for photography and new media. Shadid is a contributing editor with Infrasonica, a digital platform of “non-Western cultures” for experimental sound and visual art practices. Most recently she directed the 2022 Berlin Biennale Curator’s workshop and was a curatorial resident at Ashkal Alwan, April-October 2021.

Shadid became director of Beirut Art Center on Jan. 1, 2023.

“It’s important to take some time to really understand what is necessary,” she reflects. “When I say ‘What’s necessary,’ it’s not just reacting. It’s not just ‘Artists need money.’ Of course, artists need money,” she laughs.

“It’s more about building, about not being stuck in this purely reactionary state of practice.”

A still from Taleb Al Saj’s metal welding workshop, staged as part of BAC’s 2023 public program. (Courtesy of: BAC)

A still from Taleb Al Saj’s metal welding workshop, staged as part of BAC’s 2023 public program. (Courtesy of: BAC)

The story so far

BAC was founded in 2009 in a warehouse-peppered tangle of autostrade and flyovers near the Beirut River en route to Sin al-Fil, called Jisr al-Wati. Before the rise of loft spaces and condominiums there, BAC, Ashkal Alwan and Station Beirut transformed this light-industrial zone into the city’s premiere contemporary art hub.

BAC was Lebanon’s first nonprofit space for exhibiting contemporary art by established and rising international and regional artists. The project was the brainchild of gallerist Sandra Dagher and artist Lamia Joreige — staging a succession of widely varied solo and group exhibitions, enlivened by a rich public program of artist and educational talks, performances and film projections. It hosted regular events like Irtijal, Beirut’s experimental music festival and Ashkal Alwan’s Home Works contemporary art forum.

By the time French curator Marie Muracciole took the helm (2014-2019), BAC numbered among the city’s few robust contemporary art institutions — alongside Ashkal Alwan and a few associations and commercial galleries. Muracciole’s final Beirut show was staged in the summer of 2019 at BAC’s current home, another former industrial space in Jisr al-Wati a few minutes’ walk from the original location.

BAC’s rooftop, captured here during an event in May 31, 2022, will remain a place "to think and to gather and do workshops." (Courtesy of: BAC)

BAC’s rooftop, captured here during an event in May 31, 2022, will remain a place "to think and to gather and do workshops." (Courtesy of: BAC)

BAC was officially rudderless when Lebanese took to the streets demanding change in the fall of 2019. As the exuberance of the uprising was shuttered by the stasis of COVID-19 lockdown and the depression of collapse, the keys were handed to three younger faces from Lebanon’s art sector. The artistic director’s chair was shared by artist Haig Aivazian and filmmaker/artist Ahmad Ghossein (who soon had to leave the post) while Rana Nasser-Eddin, whose background was in gallery management, was named administrative director.

Aivazian, Ghossein and Nasser-Eddin focused on how to keep BAC relevant amid the crises. Local artists were invited to apply for a new series of Micro-commissions, with BAC exhibiting completed works (virtually and physically), while a residency program was instituted for artists and designers.

The Derivative, an imaginative online publication for local and international artists and practitioners, was launched, while the center’s rooftop hosted a series of performances and workshops as well as a community garden. Aivazian and Nasser-Eddin stepped down in December 2022.

Lingering challenges

Shadid is excited by BAC’s possibilities, though contingencies have a way of dampening enthusiasm.

“Every morning you’re reminded that you have a ton of things to do besides thinking of an artistic program for the center,” she says, “but it’s also been super exciting to think of what can happen in this space and what it means for Beirut.”

Several challenges awaited Shadid when she took the helm — some expected, others less so.

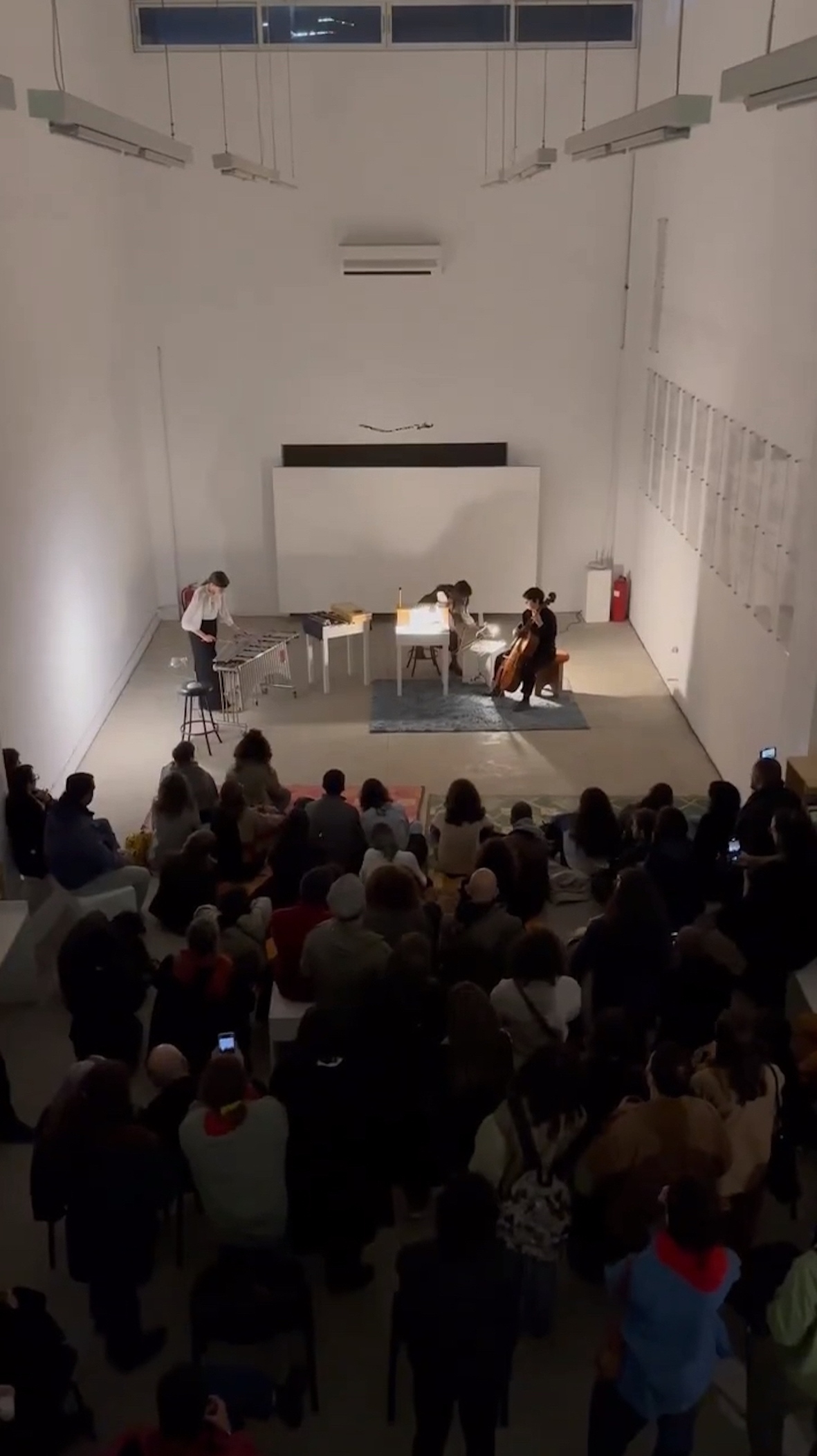

A still from “Music For Corridors (And Other In-Between Places)” a concert from BAC’s 2023 public program, featuring Christelle Njeim, Yara Asmar, Youmna Mroue. (Courtesy of: BAC)

A still from “Music For Corridors (And Other In-Between Places)” a concert from BAC’s 2023 public program, featuring Christelle Njeim, Yara Asmar, Youmna Mroue. (Courtesy of: BAC)

“Our generator completely died my third week on the job,” she laughs. “If there’s no electricity we can’t keep the doors open, and there are exhibitions up and events scheduled. That was one of the expected challenges,” she laughs again, “but maybe sooner than I expected. You’re immediately aware all this money is going toward the generator and trying to think of alternative solutions that are affordable.”

Funding problems are among the challenges Shadid expected. While BAC’s board of directors conceived of the center’s previous administration as a tripartite one, it now has one director, responsible for maintaining the space, planning and executing programming.

Since the handover period with Aivazian and Nasser-Eddin, Shadid says the admin and finance side of BAC’s operations have taken up much of her attention.

Programming beyond the crises

Much of Shadid’s past experience in arts administration comes from her time with the Sharjah Art Foundation, easily the most vital incubator and engine of contemporary art production and exhibition in the Gulf, and among the most important in the MENA region. She served as deputy director of SAF from 2006 to 2020, where she ran operations. Though her current post is more senior, she says the two jobs are not dissimilar. The challenges, however, are distinct.

The library in BAC’s central hall, the canvas for a new yearly commission for architects and artists. (Credit: Maria Klenner/L’Orient Today)

The library in BAC’s central hall, the canvas for a new yearly commission for architects and artists. (Credit: Maria Klenner/L’Orient Today)

“Very different. I mean, besides not having to worry about money or economic and socio-political problems,” she laughs, “it’s largely a difference in audience ... I’m building on a lot of my experience from Sharjah, where I worked with the education and curatorial teams. At BAC I’m working with my colleagues to introduce a more regular structured public [education] program that is relevant and responds to the context and different publics.

“It’s about engaging with more people with different experiences and different backgrounds, but also trying to use Beirut Art Center in the program as a way of processing and thinking about what’s happening, ... How can we continue? How do we build despite this constant reactionary state that we are in?”

One successful COVID-era initiative that Shadid must reluctantly pause is The Derivative.

“The Derivative was one of my favorite publications before I started working at BAC,” she says, “but it’s a very large endeavor and it’s quite expensive. It’s called The Derivative because of the structure that it was built around — thinking of how you share and extend resources as much as you can while building a network that’s working toward common goals. I really appreciate that, but it’s a super expensive project for me right now. I’d like to continue publishing at some point, but I have to rethink the format or frequency in a way that’s more appropriate for the times.”

Shadid says BAC’s programming structure will incorporate new approaches into BAC’s earlier initiatives.

“I feel it’s important to build on what people have done. Beirut Art Center has had an interesting program and there’s no reason to completely overhaul it and change it. Some programs are building on what Haig and Ahmad have done. Some are new propositions and proposals for my time, a way to experiment with what might work or what the art community needs here.”

BAC’s public program will be marked by regular events to engage with both practicing artists and a more general audience.

“We have a learning in mediation program, which started in February,” she says. “This includes skills workshops for children and for youth and adults. So we’re restarting the children’s education program that was in place before [the crisis].

“Then we have more discursive programs that are concerned with art practices. It might be artists’ talks or symposia, conversations or lecture performances around how we think about artistic practice, what the role of art is now. How do we approach it?

“We also have a library program and workshop collaborations. These are not totally developed, but they’re in the works. We also have a film program, so monthly film screenings organized around themes — whether related to current exhibitions or more general questions around art-making. We have a regular performance and music program, a space for experimental musicians and sound, which also stems out of my interest in and research on sound art and experimental music.”

The commissions and residencies will remain in place, Shadid says, but “slightly changed to fit the time.”

“The artist in residence and graphic designer in residence will continue as usual, upon invitation. There are now several categories within BAC Commissions, formerly called Micro-commissions. The Neon Commissions will continue, as a way to think of the economy of arts and as a kind of proposal to find a solution for self-sustainable funding.

“I’m also introducing a site-specific architecture-art commission for BAC’s central hall. Once a year the commission will transform the space according to conversations that are going on with the invited artists or architects. And of course, we have the rooftop, which will continue its function as a place to think and to gather and do workshops.

“The object is to engage people,” Shadid says, “to have people come in and find a space that they’re interested in, and that makes them feel comfortable. We want to open the doors a little bit wider, for people to start engaging with programming. Not just coming to BAC, but sharing what they would like to see or what they’d like to do here.”