A still from ‘Aida Returns’ showing Carol Mansour, right, and Tanya Habjouqa transferring Aida Mansour’s remains into ziplock bags in preparation for their return to Jaffa. (Credit: Forward Films)

BEIRUT — “You keep saying, ‘It’s a sad movie,’ but lots of people tell me they laughed a lot too,” says Carol Mansour. The filmmaker is emerging from ten days of flu, and the odd cough distorts her voice almost as frequently as the glitches of the ADD-afflicted internet connection.

“The story has many layers.”

Indeed, the emotional landscape of Mansour’s latest film is one of striking contrasts. The star of Aida Returns is the filmmaker’s mother, whose death is, naturally, a source of grief. Her departure is the premise but not the subject of this film, which documents a cunning plan — hatched by the filmmaker and her producer — to repatriate Aida to her birthplace, Jaffa, Palestine. The execution of this subversive plot twinkles with good humor.

Backstories

Mansour is among Lebanon’s more prolific documentary filmmakers. Generally her canvas is Lebanese society and in the past few years she’s made several films scrutinizing facets of the Syrian refugee experience and stories of women who labor as domestic servants.

The filmmaker’s intimate proximity to her subject in Aida Returns marks a departure from Mansour’s usual work.

The film’s protagonist Aida Mansour, née Abboud, shares a family history common to many Lebanese of Palestinian heritage. When Jaffa was under fire, the Abbouds fled to Beirut in 1948, fully assuming they’d return in a few weeks or months. When that proved impossible, they went about the business of living. Aida met Michel Mansour. They married, raised a family and eventually migrated to Canada. Toward the end of her life, Aida’s health declined.

“The toughest part of making this film was that I really didn’t want it to be personal,” Mansour says. “I didn’t want to put any family pictures.”

The biographical segments of Mansour’s film do draw upon a generous cache of still images from her mother’s life in Palestine, Lebanon and Canada, which include her husband and family. Complementing the stills is a 2007 interview in which the mother vividly recollects leaving Jaffa. Then there are the less formal conversations with her mother late in life, when she was more or less lucid as dementia took its toll.

“I started filming her in Montreal when her memory started slowly, slowly, deteriorating,” the filmmaker recalls.

“I went to Canada like 21 times in three years, just to be next to her. You know how human beings deal with loss. I was just filming her with my phone, to keep the good memories. I had no intention of making a film.”

Memory and return

It isn’t uncommon for Lebanese filmmakers to turn their lens on family members. In 2006, for instance, contemporary artist and performer Lina Saneh released her striking I Had a Dream, Mom, in which the artist and her dementia-afflicted mother discuss a dream the artist had, one that might be a precis of cultural life in Beirut at that time.

Since the protagonist of Mansour’s film was born in Palestine, Aida Returns is entangled in two themes that are recurrent in Palestinian cinema. One is memory. Another is return.

A still from ‘Aida Returns’ showing Raeda Taha sneaking into the courtyard of the former Bayt Abboud, in Jaffa. (Credit: Forward Films)

A still from ‘Aida Returns’ showing Raeda Taha sneaking into the courtyard of the former Bayt Abboud, in Jaffa. (Credit: Forward Films)

Perhaps all displaced communities are in a running battle over memory. As one aphorism puts it, “The old will die and the young will forget.” (In Samir Nimr and Monica Maurer’s 1980 documentary The Fifth War, Venessa Redgrave ascribes this line to one-time US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.) Consequently Palestinian documentaries have cultivated stories from that generation who survived the Nakba as documents of a displaced national heritage. Memory devouring conditions like dementia and Alzheimer’s disease become a metaphor for national erasure.

Return has been explicitly denied to members of the Palestinian refugee community, imbuing even the most banal deaths with political meaning. Lebanon-born Palestinian filmmaker Nasri Hajjaj tapped into this with his poetic 2007 documentary Shadow of Absence. Hajjaj takes his camera to dozens of locations around the world to document where Palestinian refugees have been buried — from anonymous mass graves, to those of notable figures like Edward Said, “Handala” creator Naji al-Ali and Khalil al-Wazir (aka Abu Jihad). If denial of return makes Hajjaj’s lyrical road trip melancholic, then the subterfuge of Aida Returns makes it surprisingly buoyant.

The plot

It took Mansour five years to complete this film.

“When she passed away in 2015, I didn’t have the energy to watch the footage that I’d filmed. Last winter I started looking at those rushes, and what I had shot in Beirut in 2007.”

“I kept her ashes at my home for maybe two years. Then, while my friend [East Jerusalem-based photojournalist Tanya Habjouqa] was here, [the film’s producer Muna Khalidi] told me, ‘Just give the ashes to Tanya. At least they’ll be in Palestine. Then we’ll figure out what to do.’ Tanya and her friend [journalist Peter Van Agtamael] said they were excited to help out.”

The film documents Mansour placing Aida’s ashes in a double pair of ziplock bags — it being reasoned that if one of the couriers was stopped and searched, at least part of her remains would return.

Once Habjouqa and Van Agtamael cross Allenby Bridge into Palestine, they pause to take a portrait of Aida (one of the two ziplock bags is captured, sitting up in the car, secured with a seatbelt) and collect co-conspirator Raeda Taha, a well-known Palestinian playwright, actress and activist.

“Raeda was the best person to look for my mother’s house and bury her,” the filmmaker says. “This is how the film started to be.”

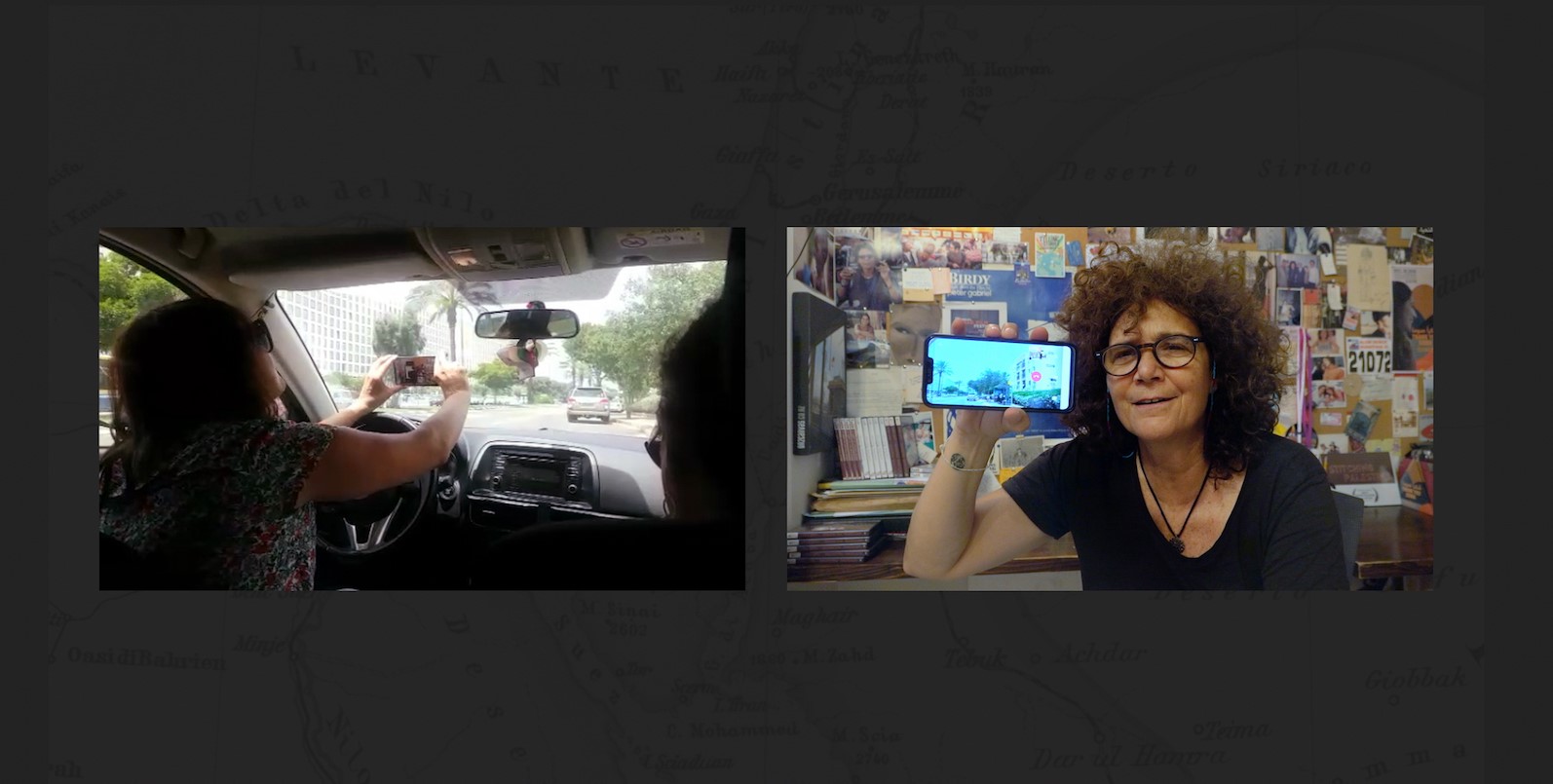

Five different formats of video were used to make Aida Returns, with Mansour, Habjouqa, Van Agtamael, as well as Angelique Abboud and Randa Shaath acting as camera operators. The round-trip to Jaffa was the most technically complex to capture. While the smugglers filmed their journey across Palestine, Mansour (in Beirut) was communicating with them by video call, a conversation that was filmed in both Lebanon and Palestine.

A still from ‘Aida Returns’ showing Tanya Habjouqa, left, outside Jaffa, and Carol Mansour in Beirut. (Credit: Forward Films)

A still from ‘Aida Returns’ showing Tanya Habjouqa, left, outside Jaffa, and Carol Mansour in Beirut. (Credit: Forward Films)

Though phone batteries seemed to run down at inopportune moments, the plot to repatriate Mansour’s mother goes to plan remarkably well. An elderly gentleman in Beirut who knew the Abbouds in Jaffa scrawls a map showing the location of Aida’s house in the Ajami neighborhood. Another, the grandfather of a young fellow they meet in Ajami, directs them to the precise location.

Documentary film in high-security areas has undergone some changes in the past couple of decades. It’s not uncommon for filmmakers to re-enact dramatic sequences that circumstances prevent them from filming first hand. Sometimes, the reasoning suggests, the object is to capture truth, whether it is cinema-vérité or not. The skeptic wonders if Mansour and her co-conspirators were tempted to re-create Aida’s burial.

A still from ‘Aida Returns’ showing Raeda Taha, left, in Jaffa, and Carol Mansour in Beirut. (Credit: Forward Films)

A still from ‘Aida Returns’ showing Raeda Taha, left, in Jaffa, and Carol Mansour in Beirut. (Credit: Forward Films)

Mansour is stridently old school.

“Reenactment? Are you kidding?” she says, coughing. “Not at all. My god. You cannot re-enact something like this. It’s dishonest. This is a documentary, documenting something true.”

It takes a few minutes for Taha, Habjouqa et al to walk to the old Abboud house, now occupied by a non-Palestinian family, and they find no one at home. Later they happen upon a cemetery with several graves belonging to members of the Abboud family, dating from the 19th century. Finally they step onto a quiet beach frequented by Palestinians, where they can wade into the Mediterranean with their cameras.

“This sea is mine!” Taha intones as she approaches the beach, her voice dropping an octave to approximate that of the poet, Mahmoud Darwish.

The gesture is poignant, and comic.

“This humid air is mine!” she shouts as she steps on the sand. “And my sperm is mine!”

“The story has many layers.”

Indeed, the emotional landscape of Mansour’s latest film is one of...