Monika Borgmann in the document stacks at UMAM's archive. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

BEIRUT — Monika Borgmann is on the move, striding into the warren of archives at the Badaro offices of UMAM Documentation and Research, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving Lebanon’s contentious memory. Here are housed the remains of Baalbeck Studios, the film and music production company that was once central to Lebanon’s fledgling cinema industry.

“We were able to get these machines,” she says, pausing to sweep a hand over the hardware arrayed on various desks and tables in one room, “thanks to the French, to digitize sound from any format.”

Marching onward, she swings open the door of a room crowded with shelving stuffed with orderly document boxes and file folders. “Studio Baalbeck’s written archive,” she nods. “A box for each film’s documents — a lot of contracts, invoices, entire correspondence about what was paid, what was not paid, about technical errors etc.”

A postcard photo of the late Egyptian film star Omar Sharif. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

A postcard photo of the late Egyptian film star Omar Sharif. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Intriguing anecdotes are scattered amid the production details. Among them is a 1966 correspondence with Egyptian auteur Youssef Chahine, seeking financing for a project titled “Kingdom of Heaven,” his (never completed) screen adaptation of Andrée Chedid’s novel “The Survivor.”

“The films’ histories are wonderful,” Borgmann smiles. “Then you have the staff folders. When you go through them you find the real memory. They provide insight into how this production company actually worked.”

Baalbeck Studios’ technicians were Lebanese and Palestinian. After 1975, Palestinian staffers had difficulty getting to the studio’s Sin al-Fil offices, notably during the siege of Tal al-Zaatar, so for a couple of years they had to work from a different location on Beirut’s Airport Road. The company had a wide range of regional and international partners and its clients included militant organizations funding filmmakers to tell stories of the Palestinian revolution. The Civil War disrupted these business relationships.

Borgmann reaches around a corner and produces several large framed documents, architectural plans for film production facilities that Baalbeck Studios intended to build in the mountain town of Monte Verdi. “They really wanted to go large,” she muses. “They had dreams of building a new Hollywood, if you want.”

Borgmann says some of the materials in UMAM D&R’s archive were found littering the floor of Baalbeck Studios and in the trash. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Borgmann says some of the materials in UMAM D&R’s archive were found littering the floor of Baalbeck Studios and in the trash. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Another room is devoted to film stock and negatives. These shelves have been largely depleted, Borgmann explains. Most of UMAM’s holdings, Baalbeck’s domestic production, have been shipped to Berlin. There, the prints and negatives are being cleaned and digitized by conservationists at Arsenal (Institute for Film and Video Art), UMAM’s partner in the Baalbeck Studios project.

It was challenging finding a partner. Borgmann initially approached France’s INA (National Audiovisual Institute) and CNC (National Centre of Cinema) in 2011-12 but to no avail.

“Lebanese bankers renovated the [French Institute’s] Cinema Montaigne,” she recalls. “So when it re-opened in 2013, all the bankers were there. We programmed a restored film that night, thinking the bankers would also become interested in saving this collection.”

She takes out a cigarette and chuckles. “They did not become interested.”

Turning to another shelf, she opens one of the perhaps 30 boxes there to reveal the cut and uncoiled lengths of footage within.

Monika Borgmann poses with a ledger, part of UMAM D&R’s archive. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Monika Borgmann poses with a ledger, part of UMAM D&R’s archive. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“It’s not yet clear what these are,” she explains. “There may be hundreds of meters of footage like this that need identifying.”

For anyone focused on Lebanese cinema since 1990, the year the Civil War nominally ended, the notion that the country once had a nascent film industry might come as a surprise.

The work that’s captured most international attention since the late 20th century — whether its trove of documentary and nonfiction works, the auteur-inspired fictions and artworks of filmmakers such as Ghassan Salhab, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige or the more-commercial, genre-inflected fiction work of directors like Ziad Doueiri and Nadine Labaki — has had an international flavor. This tang is redolent of the artists’ inspiration, training and financing but also the country’s want of domestic film industry infrastructure.

Most Lebanese filmmakers must run the gauntlet of international film-development labs, co-production markets and a handful of funds — once mostly European, now more likely to be regional. In the wake of the 2019 financial collapse and later global troubles, their challenges have multiplied.

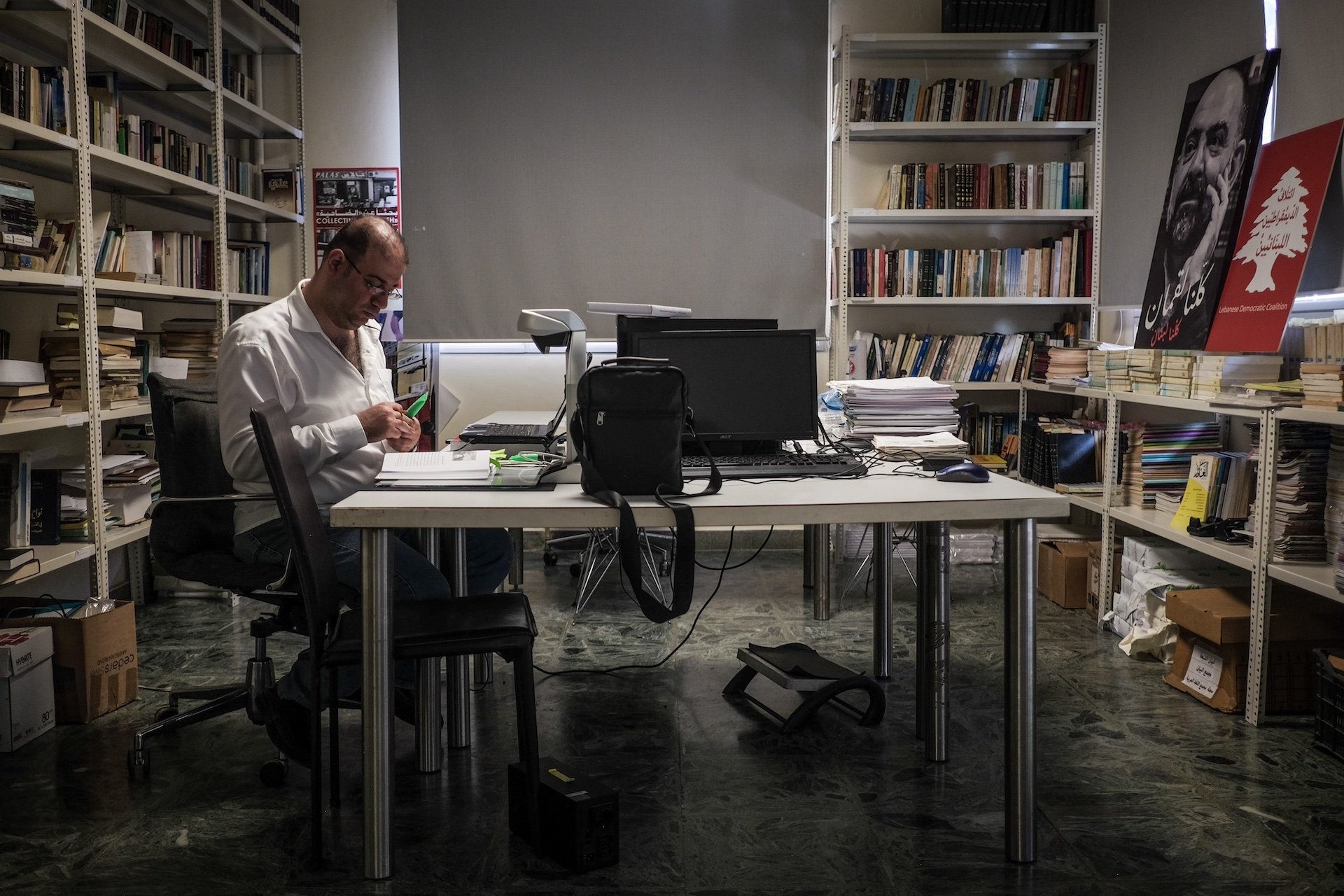

UMAM senior researcher Abbas Hadla examines some Baalbeck Studios documentation. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

UMAM senior researcher Abbas Hadla examines some Baalbeck Studios documentation. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

“These Egyptian guys who released their first films around the same time as me?” a Lebanese filmmaker recently confided from atop his Vespa. “They’re all making a living now — shooting ads, television series ... Here, nothing. I guess I should have been an Egyptian filmmaker.”

This was not always so.

Lebanon’s pre-war cinema scene

“By the mid-60s, you had the infrastructure to make an entire film in Lebanon,” says documentarian Hady Zaccak, “from pre-production to post-production, with a Lebanese crew.”

Zaccak has an intimate knowledge of Baalbeck Studios (1963-1995). Swathes of his 1995 debut film, “Pioneers of Lebanese Cinema,” were shot at its facilities just before the company shut down. It has been part of his film studies curriculum and he’s taken his students to examine UMAM’s holdings.

“During this period there were plenty of co-productions between Lebanese, Egyptian, Syrian, Turkish and Iranian producers,” he says. “There were several Italian films and European co-productions.”

Filmmaker Ayman Nahle, an audio-visual archivist at UMAM, examines film in organisation’s Baalbeck Studios archive. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Filmmaker Ayman Nahle, an audio-visual archivist at UMAM, examines film in organisation’s Baalbeck Studios archive. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Aside from Baalbeck’s in-house films and co-productions, its facilities might be involved in various aspects of other films shot in Lebanon and the MENA region — whether providing financing or equipment, line production, developing footage, recording scores or dubbing dialogue into other languages. By the end of the ’60s, both Baalbeck and Haroun studios (its principal competitor) had upgraded their facilities to develop color film, previously sent to overseas labs. The footage for most all Middle East newsreels (the principal means of distributing audiovisual news and current affairs content before television) passed through the studio for processing.

Several local factors drove the development of the local cinema scene — Lebanese film distributors’ decision to start producing their own movies, for instance — but external factors always played a role in the country’s domestic film industry, not least the Egyptian state’s gradual nationalization of the country’s film industry, the most robust in the Arab world.

“Lebanon’s liberal economy drew Egyptian filmmakers here,” Zaccak says, “whether Egyptian projects or Egyptian-Lebanese coproductions. This is how the number of locally produced films increased yearly, reaching a peak in 1965-67.”

While Gamal Abd al-Nasser’s state socialism was a boon for Lebanon’s cinema, political instability (regional and domestic) ensured the industry’s fragility.

Negatives of still images, part of the UMAM's archive are examined on a light box. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Negatives of still images, part of the UMAM's archive are examined on a light box. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Unlike contemporary Lebanese cinema, Studio Baalbeck’s films were very commercial. In addition to the Egyptian movies, there were Lebanese-Turkish co-productions, notably from the mid-60s to the early 70s, and several European spy flicks were shot in the country between 1964 and 1967.

“It’s worth noting that in the 60s, while you have all these international cinematic movements — the New Wave, the new Brazilian cinema and so on — in Lebanon there was not really a film d’auteur,” Zaccak says. “For that we had to wait until the 70s.”

During the first two years of the civil war, film production effectively stopped in Lebanon, but the studios returned to work by the late 1970s. Baalbeck Studios produced several action movies in the early 80s as well as film scores and pop songs, but the financial crisis and currency collapse of the mid-1980s hampered film production. Though some films were processed in the early 1990s, age and lack of investment had taken their toll on Baalbeck Studios’ production and development equipment. The studio shut in 1995.

Clearance sale

UMAM D&R received a phone call in 2010 informing them that the modernist building in Sin al-Fil that housed Baalbeck Studios had been scheduled for demolition and that its contents were for sale.

“A lot of people came and bought furniture,” Borgmann smiles.

Some of the strips of cut footage that Borgmann, Slim and their team collected at the start of their Baalbeck Studios conservation project. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

Some of the strips of cut footage that Borgmann, Slim and their team collected at the start of their Baalbeck Studios conservation project. (Credit: João Sousa/L’Orient Today)

By that point Baalbeck Studio’s archive of in-house productions and co-productions had been removed by workmen sent by Intra Investment — the institutional successor of the storied Intra Bank after its crash and dismemberment in 1966.

“To my knowledge, the films were first stored in Intra Bank’s basement, then moved to the Ministry of Culture,” Borgmann says. “The Ministry of Culture later gave the films’ soundtracks to USEK [Holy Spirit University of Kaslik] and the film prints went to NDU [Notre Dame University–Louaize].

“When we arrived, there was footage still in the [film processing and copying] machines, on the floor, in trash cans — yaani you had to get dirty.”

Baalbeck Studios’ headquarters was kept intact after news of the 2010 demolition plan provoked a public outcry. Borgmann laments that the facility hasn’t been retooled as a film museum, that the studio’s vintage production and processing equipment appears to have been sold for scrap.

Film researchers have been working on UMAM’s Baalbeck Studios archive since 2010 — with researcher Nathalie Rosa Bucher organizing the written archives and audio-visual archivist Ayman Nakhle working on the footage — to ascertain what the archive contains.

“It’s a kind of puzzle,” Borgmann reflects, lighting a cigarette, “a process of matching. A lot of rushes had no titles, no info at all. When we started receiving the digitized film material last year, we invited some friends, mainly from the older generation, to watch and identify the material in the rushes with us. It’s an ongoing process.

“We have rushes,” she says. “We have rough cuts and trailers. We have material that never made it into the finished films — the director shot a scene four times, decided on one of them and left us the rest.”

For film scholars and historians, this archive is far more precious than the finished films (copies of which are stored elsewhere), both for the fragments’ documentary value and for what they, and the printed documents, reveal about filmmaking practices during Baalbeck’s brief florescence.

Going public

Borgmann cofounded UMAM D&R in 2004 with her late husband, publisher and political commentator Lokman Slim, who was murdered in South Lebanon in early 2021. To date the perpetrator has not been officially identified, apprehended or punished. It obviously casts a pall over the work of the organization as much as it does Borgmann herself, whether the subject is raised or not.

“Since Lokman and I launched UMAM, our aim was to build what we called a citizen archive,” Borgmann says, “accessible to all.”

To make the Baalbeck Studios archive accessible to all, UMAM is in the midst of redesigning and diversifying UMAM Biblio — an online catalogue dedicated to its disparate holdings and print publications. Published in Arabic and English, the organization's Baalbeck Studios pages will have links to a range of studio productions — footage and/or soundtracks from several movies, Lebanese and international newsreels (formerly projected before feature films) — and samples of the paper trail left by individual films Baalbeck produced. The object of this online teaser is to entice researchers, journalists and artists to come dig into the archive creatively.

“The archived footage is beautiful in itself,” she says. “The question is how do you bring it back to life, so it can have an impact today? We’ve had workshops with artists, and people have already been using the small part of the holdings that have been digitized. During Arsenal’s Archive Days, Ayman did a workshop on using this kind of material to make a film that speaks to contemporary issues.”

Borgmann lights a cigarette.

“We wanted to start this process by first holding an exhibition,” she gestures to a framed ad on the wall of the conference room, comprised of images from the studio archive. “It is ready. The idea was to open on Nov. 2 2023, with events — talks, a cine-concert, etc — until the end of December, then to open up everything to the public.

“But since Oct. 7 it is not a time to celebrate, so we are further developing the webpage and waiting for a more appropriate occasion … Ideally we would like to mark the re-launch of UMAM Biblio with this exhibition on June 9, International Archives Day.

“People will know what they can find at UMAM or at NDU or Kaslik. I believe this is an important service, even if the archive isn’t all located in one common space.” She pauses. “I had this discussion with friends and collectors and people who are also working with archives. Let’s imagine we want to have one space for an archive. Where would you put it? What would be a safe space in Lebanon?

“We didn’t find an answer. Maybe it’s safer if it’s not all in one place.”