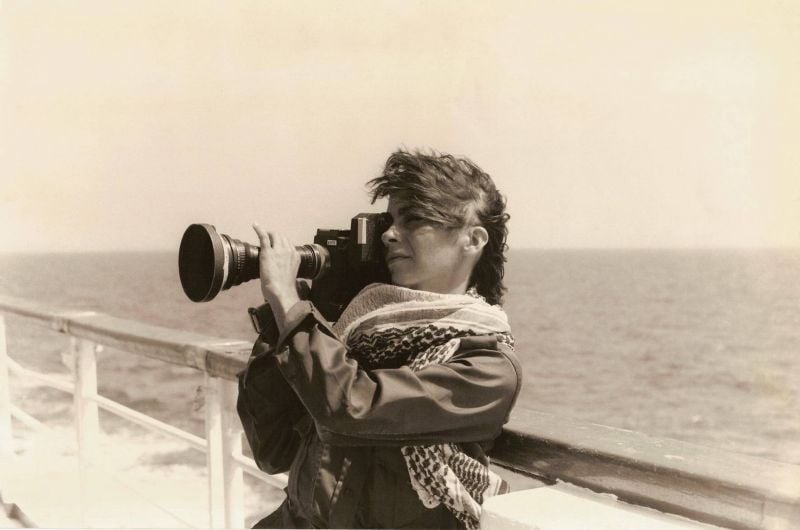

Jocelyne Saab during the shoot of her 1982 film ‘Ship of Exile,’ about the evacuation of PLO fighters from Beirut. (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

BEIRUT — Mathilde Rouxel encountered the work of journalist and filmmaker Jocelyne Saab by chance. As a graduate student, she decided to study Arabic in Lebanon.

“I came across an interview with her,” Rouxel recalled with a smile. “She was saying that Lebanon’s Civil War wasn’t a sectarian conflict but a class struggle.

“I met her in 2013, as she was preparing to launch the [Cultural Resistance International Film Festival] in Tripoli. I became her assistant. She was used to having many young people supporting her, exploiting them,” she laughed. “She didn’t have copies of most of her films, but ultimately she gave me what she had.”

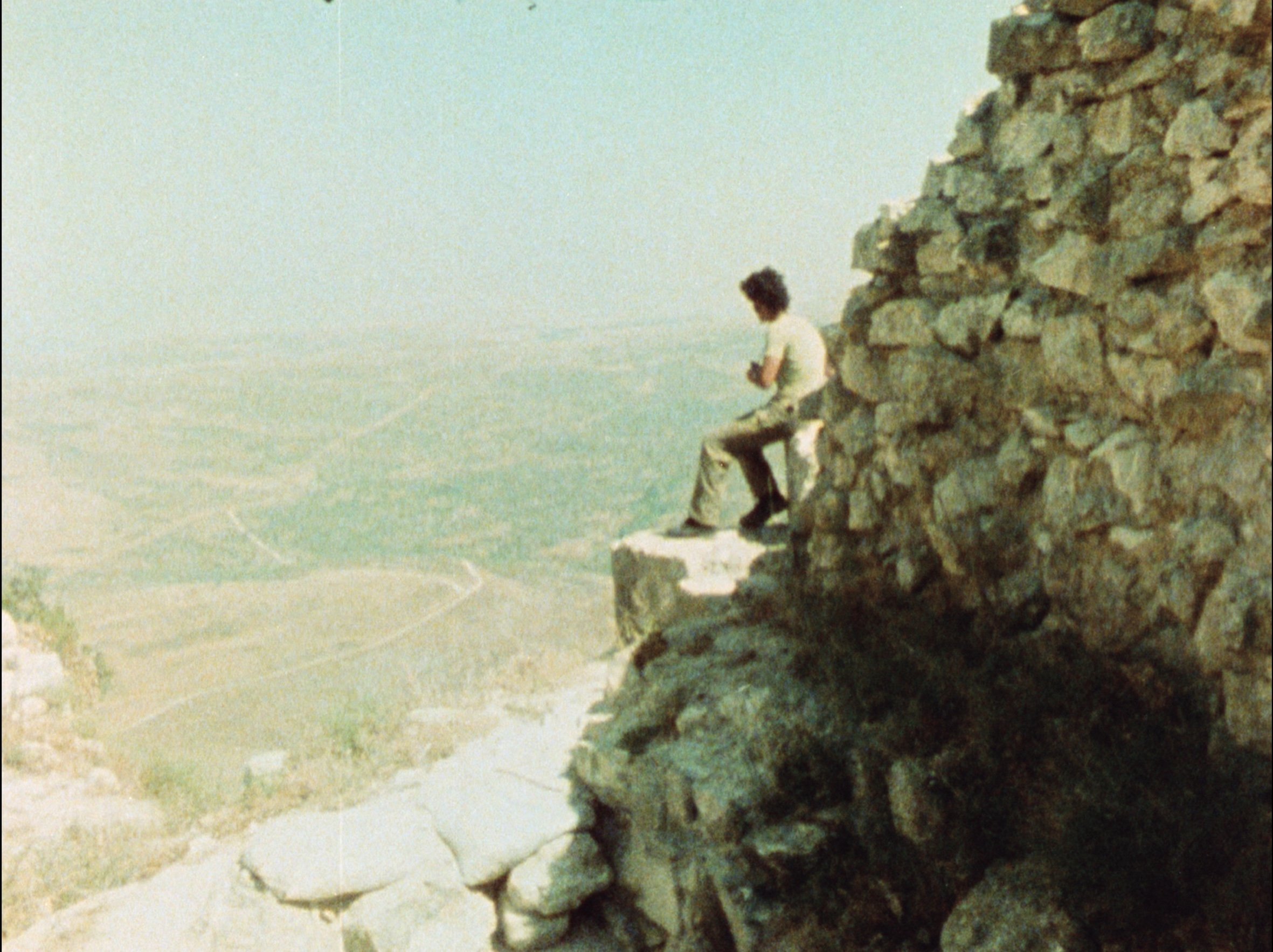

A still from Saab’s 1978 film ‘Letter from Beirut.’ (Courtesy of Jocelyne Saab Association)

A still from Saab’s 1978 film ‘Letter from Beirut.’ (Courtesy of Jocelyne Saab Association)

A film historian and independent curator specializing in Arab cinema, Rouxel wrote “Jocelyne Saab, la mémoire indomptée” (Beirut: Dar an-Nahar, 2015), the first book dedicated to Saab’s oeuvre. After the filmmaker passed away in 2019, Rouxel became president of the Jocelyne Saab Association, responsible for preserving and disseminating her work.

Rouxel has been in town for projections and discussions of Saab’s work at the French Institute (IF), IESAV (USJ’s Institut d’études scéniques, audiovisuelles et cinématographiques) and ALBA (Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts). She’s also toting the first harvest from the association’s digital restoration initiative — a box set of films Saab made between 1974, when the French TV reporter started making films independently, and 1982 when she left Lebanon.

“Jocelyne was fighting for internationalism. People were still dreaming of a better world in those days,” Rouxel mused, “before Israel invaded in 1982.”

A still from Saab’s 1982 film ‘Beirut, My City.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

A still from Saab’s 1982 film ‘Beirut, My City.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

Restoration amidst migration

The Saab Association began staging training sessions in digital film restoration in 2021, in collaboration with Cinematheque Beirut, the Marseille film production facility Le Polygone Étoilé and Beirut post-production house The PostOffice. For the next round of workshops, scheduled for May 15-24 2024, Rouxel decided to collaborate with ALBA and IESAV so that trainees emerge with university accreditation.

“The people I’m working with are dreaming to go to Europe and find a job,” Rouxel said. “This is difficult. In Europe, if you don’t have a certificate proving that you have skills, it’s as if you have no skills.

“We may work with PostOffice this time as well, because they bought the license for the digital restoration software, and they have some experience from the previous workshop and the restoration work they did on three or four of Jocelyne’s films.”

Ordinarily, such hands-on mentoring would deepen the pool of local talent in the film restoration field. In the wake of Lebanon’s economic collapse, the training sessions are replenishing a sector depleted by economic migration.

“Two of the instructors for the workshop in May were trainees in the previous session. They’re coming back because they want to teach someone in Lebanon what they learned before leaving,” she laughed. “It’s funny, but very sad at the same time.”

All but three of the association’s 12 previous trainees have left Lebanon.

“A sound engineer [trained in restoration] left to France,” she said. “A participant working in color grading quit restoration but she’s been working in Lebanon and is helping with our restorations. One trainee now works at PostOffice. Another is working with me.”

Other participants in the previous training session are still looking for jobs. “They work with us too but have other activities on the side,” she said. “In one case, she’s doing subtitles for a French post-production company, so she’s helping us with that as well. Another is now working at a film archive in Canada.

“Everyone is leaving Lebanon. That’s why I’m like, ‘No, we need to do more training to have people working here!’”

A unique body of work

Jocelyne Saab’s archive of 40-plus finished films is secure. When she was preparing her 1984 docu-fiction “Once Upon a Time in Beirut,” Rouxel explained, Saab arranged to have the original edits of all her previous work stored at the CNC [France’s National Centre of Cinema]. Her subsequent films were held by various companies in France that had done the filmmaker’s post-production. After some years of toil, Rouxel was able to retrieve these works, most of which now reside at the CNC.

A still from Saab’s 1982 film ‘The Lebanese, hostages of their city.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

A still from Saab’s 1982 film ‘The Lebanese, hostages of their city.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

The wealth of Saab’s body of work lies, in part, in how it reflects the technological changes affecting filmmaking practice during her career. In her early work, Saab “worked on diapositives [16mm reversal film that produces positive images rather than negatives], so the films we have are working copies,” Rouxel said. “They’re badly damaged, but we have [entire films], not the material re-edited for TV broadcast. It’s very interesting to examine the traces of her practice. You feel she was working very quickly: Shooting, cutting, broadcasting.”

At first, “we didn’t know most of Jocelyne’s films,” she added. “Most hadn’t been printed and they hadn’t circulated in festivals. I found two short docs that had never been shown before her death.”

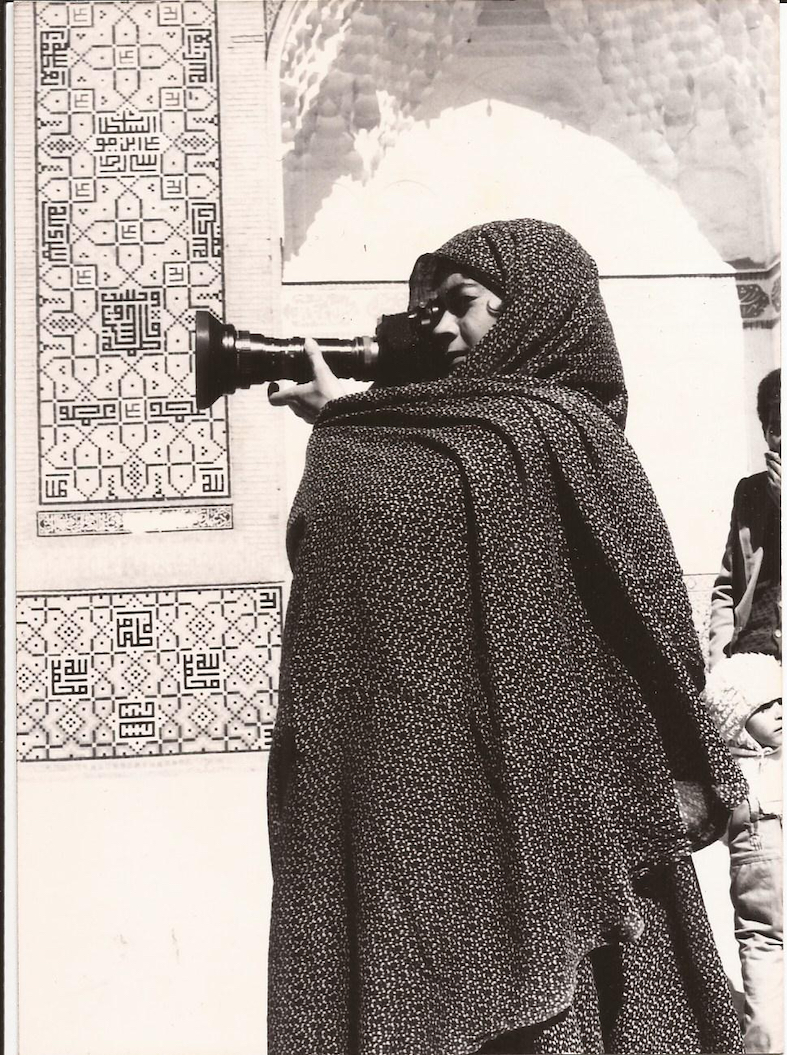

“Palestinian Women,” 1974, which follows female fedayyin being trained in Syria, was censored by French television and never broadcast; “For a Few Lives,” 1976, is a profile of politician Raymond Eddé, who ran in Lebanon’s 1976 presidential election on an anti-sectarian platform.

A still from Saab’s 1974 film ‘Palestinian Women.’ (Courtesy of Jocelyne Saab Association)

A still from Saab’s 1974 film ‘Palestinian Women.’ (Courtesy of Jocelyne Saab Association)

The filmmaker’s focus changed after leaving Beirut in 1982.

“She found it harder to find people to work with,” Rouxel said. “She had her first child as well, and she wanted to make fiction films. By the late ’80s she’d stopped shooting on film. She made maybe one film on Betacam, then shot 10 or 12 others on digital. This medium degrades easily, so we need to find ways for institutions to keep them in good condition. She shot on video as well. ‘Dunia’ [2005], her final feature-length fiction, was shot on video.

“It’s a good school to learn about archives, because Jocelyne’s is a huge body of work in very different formats, and she’s telling a very different history of the region.”

The association’s next round of restoration workshops in May will focus on Saab's work after leaving Lebanon, including her first work on 35mm film.

“We still have five Egyptian documentaries to restore. Then we plan to work on the original edit of her first feature film [‘A Suspended Life,’ 1985]. Restoring 35mm film could require more training and new skills.

“Plus we have to digitize the paper archive, which is scattered in different locations. It’s also huge — all the films Jocelyne couldn’t make between 1990 and 2020 ... I found at least 15 different projects.”

A still from Saab’s 1981 film ‘Iran, Utopia in the Making.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

A still from Saab’s 1981 film ‘Iran, Utopia in the Making.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

Saab’s legacy

The 1970s were not that long ago, historically speaking, but facets of that time that seem distinct — the prevailing optimism at the possibility of root-and-branch change, for instance, and the hope invested in militant movements like the PLO — can make it seem alien to some. Rouxel finds something familiar in Saab that makes her work and practice both sympathetic and uniquely contemporary.

Saab was staunchly nonpartisan, she said, and didn’t collaborate with filmmakers supported by the Palestinian resistance, yet some of her films do document the plight of Palestinians with sympathy and insight.

“This is something quite strong in Jocelyne’s film,” Rouxel reflected. “She’s communicating her emotions, her situation and her voice as a Lebanese Christian. She was unable to follow a party line [and] Palestine [is] not her cause. She doesn’t have a slogan to defend. Her engagement was with life and humanity more than ideas. She wanted to defend people who were facing injustice. So people can read her work differently ... This [non-militant humanism] is relevant nowadays, raising discussions about Palestinian resistance.”

Rouxel finds Saab’s career arc quite unlike that of any of her female contemporaries, particularly those in Egypt, who by the ’90s had either stopped filming or adopted a pro-regime position.

“This is something to defend, specifically because Jocelyne had an opportunity to express her view of the history of the Middle East from the ’70s to now and actually to change the medium — working with photography and video art as well as film. She was trying to find ways to speak to her time, to younger generations and to explore different ways of telling stories.”

Jocelyne Saab during the shoot of her 1981 film ‘Iran Utopia in the Making.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

Jocelyne Saab during the shoot of her 1981 film ‘Iran Utopia in the Making.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

Rouxel believes Saab’s standing will rise with time. “She was sometimes a difficult person ... Sometimes we simply cannot support difficult people,” she laughed, “even if you know that their work is great. Like [Jean-Luc] Godard. At some point, no one wanted to watch any of Godard’s new films. That doesn’t mean he’s not a great artist.”

“I understand those [Lebanese] artists of the younger generation saying, ‘Yeah, we knew Jocelyne from far but we didn’t really know her. We were too scared to approach her. Now I regret that.’

“I’m very happy that more and more students are getting involved in studying Jocelyn’s films and finding their own voice to discuss it. Her work is now an archive of Lebanese history. We need different interpretations to bring it to life.”

Nonprofit uncertainty, archival demand

It’s difficult for cultural nonprofit organizations to thrive when the world is a dumpster fire.

“The association has no external funding,” Rouxel said. “We’ve received some funding for past workshops, but now it’s very difficult. For the program in May, the French Institute will cover the instructors’ travel expenses, but we couldn’t get any other funding. Happily, the instructors are okay with working for free, or almost for free.

“This project doesn’t seem to be very interesting to the French. The project concerns this region but, as we’re based in France, I can understand why it’s difficult to find regional funding. So the only funds we have are from students’ fees, all of which will go to the instructors.

“We need to find a new way to keep this industry alive,” she sighed. “Postproduction companies in Lebanon are in a huge crisis. Everyone seems to have left for the [Persian] Gulf.

“At the same time, I feel the archive is becoming a thing for the new generation," she says, noting that long-running archiving projects like UMAM D&R, Metropolis Cinema’s Cinematheque and Lebanese cultural nonprofit Nadi Lekol Nas have been joined those of universities like NDU and USEK.

Jocelyne Saab was an internationalist, as the diversity of her body of work testifies, and Rouxel would like her association to support film restoration and alternative archives in Lebanon and beyond.

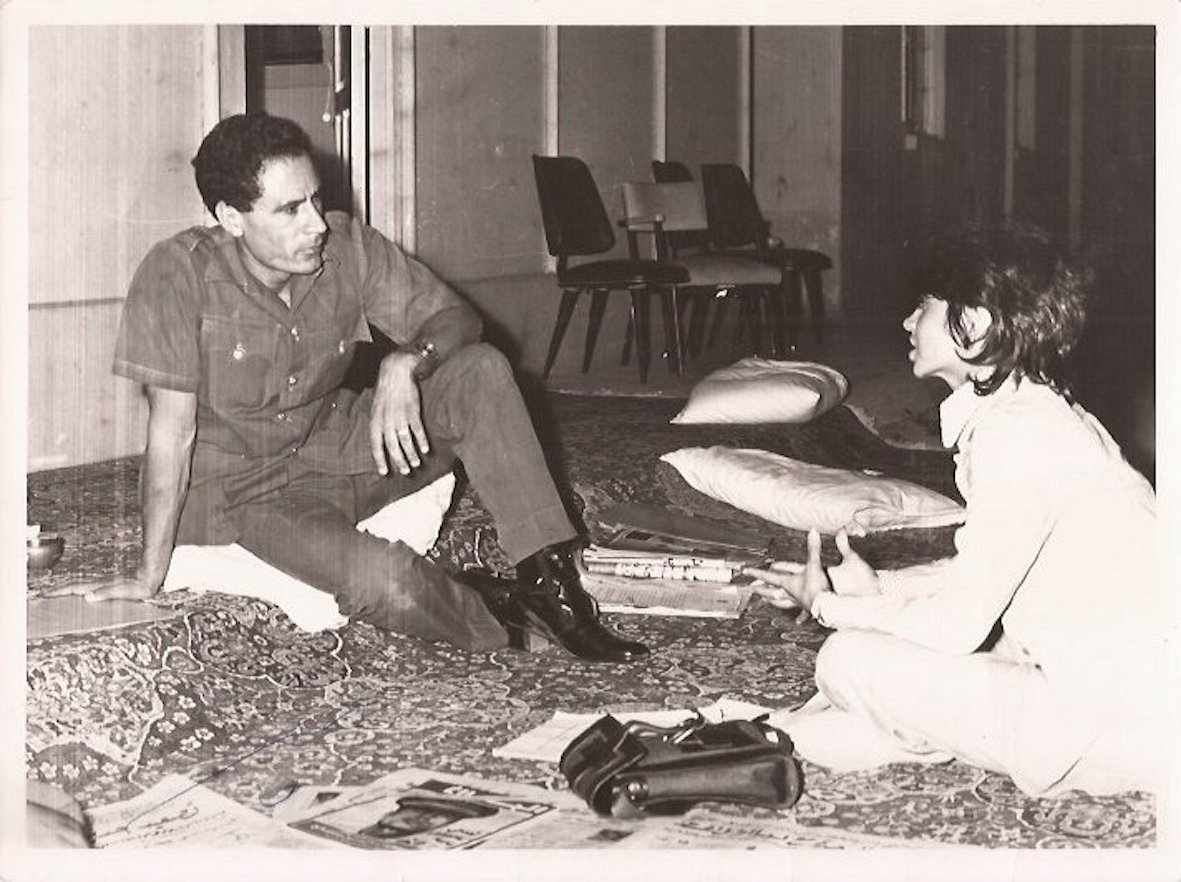

Saab Interviews Maummar Qadhafi during the shoot of her 1973 debut ‘Portrait of Kadhafi, The man who came from the desert.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

Saab Interviews Maummar Qadhafi during the shoot of her 1973 debut ‘Portrait of Kadhafi, The man who came from the desert.’ (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

“The idea is to facilitate training in the digital restoration of image, sound, and color grading to service other collections around Lebanon and the region [and ultimately] to find ways to circulate these images. We hope to help Nadi Lekol Nas restore parts of its collection and we’re restoring several Algerian and Egyptian films … I was speaking with Tunisian archivists about attending our workshops. If we can, we want to assist organizations in Algeria, Palestine and Indonesia to find, restore and disseminate their films.

“We can’t just show films whose restoration was funded by the CNC.” She laughed. “This is a nightmare. You can feel how it’s affecting our imaginations, also in Western countries. We don’t have any idea of what Palestine is because this region’s film archive isn’t circulating. It’s affecting our empathy.

“If we have the people, maybe we can do something useful to help, like creating touring circuits for archival films, like the unsubtitled Palestinian titles that we have but that no one wants to show. It’s a way to rewrite history.” She laughed. “Images are cool products that way.”

The Jocelyne Saab Association’s digital restoration training course will be held May 15-24 at IESAV and ALBA. Interested parties can contact amicale.jocelynesaab@gmail.com.

Jocelyne Saab in Egypt during the shoot of her 2005 feature 'Dunia.' (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)

Jocelyne Saab in Egypt during the shoot of her 2005 feature 'Dunia.' (Credit: Jocelyne Saab Association)