Jocelyne Saab in a still from her 1978 doc "Letter from Beirut." (Courtesy Metropolis)

BEIRUT — “We’ve been wanting to do a retrospective of Jocelyne Saab’s films since she passed away in 2019, in coordination with Association Jocelyne Saab.”

Nour Ouayda is the manager of Cinematheque Beirut, a project Metropolis Cinema launched in 2019 to preserve the memory of Lebanese cinema. Ouayda programmed Metropolis’ latest event, The Second Encounter — a film festival dedicated to cinema history that showcases classics, restored films and works that re-use archival material.

Ouayda says Cinematheque Beirut was able to move on the retrospective in the spring of 2022, when the association completed the restoration of Saab’s Civil War films, released from 1974 to 1982.

“They’d intended to restore more [of her work], but for budget reasons — and because it’s been a lengthy process — they decided to start circulating the restorations so they could use the screening fees to complete the work.”

The Saab retrospective is designed to complement another project close to the cinematheque’s mission.

“We’ve wanted to organize a symposium around film archives since 2019, so we decided to stage the retrospective and symposium together. There are a lot of other films being restored that don’t have a space to be shown in Beirut, so why not make a festival to show classics and restored films but also films that re-edit archival material? — not only a space for reverence and homage, but where we can think about these films, and stage talks about what it means to restore them and to show them today. We took the name The Second Encounter from another program of historic films that Metropolis staged in 2015.”

Still from Jocelyne Saab’s 1976 ‘Children of War’ highlighting difference before and after its digital restoration, a subject Mathilde Rouxel will take up in her talk. (Courtesy Jocelyne Saab Association)

Still from Jocelyne Saab’s 1976 ‘Children of War’ highlighting difference before and after its digital restoration, a subject Mathilde Rouxel will take up in her talk. (Courtesy Jocelyne Saab Association)

The Second Encounter opens Friday evening at the Institut Français with a projection of the 1971 detective thriller, The Choice, directed by Youssef Chahine from a script co-written with Naguib Mahfouz. The film print was recently restored and projected by Jeddah’s Red Sea Film Festival.

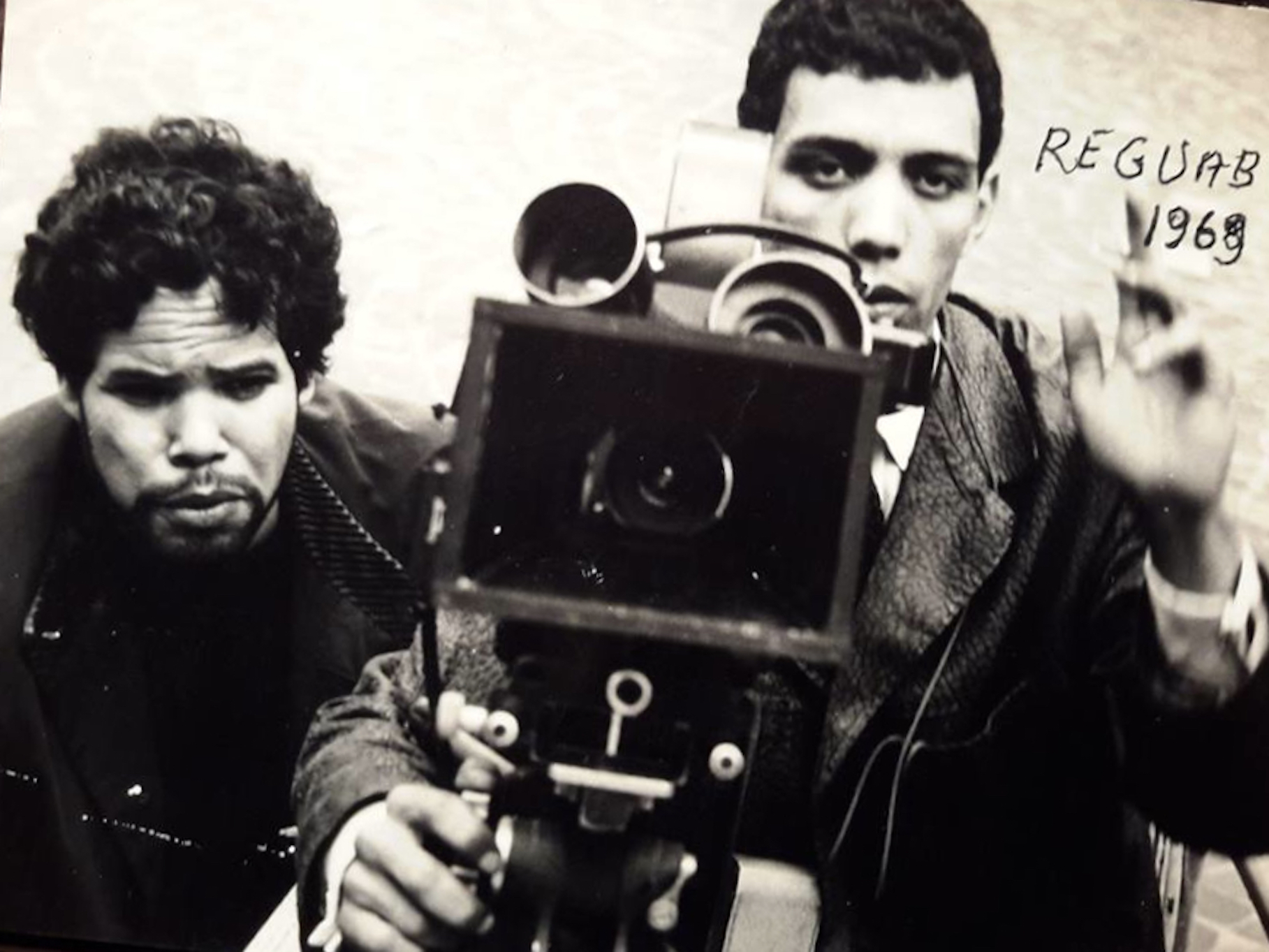

The festival will close with Mostafa Derkaoui’s 1974 experimental feature, About Some Meaningless Events, which had a single public screening before the Moroccan state censored it. The film disappeared from popular consciousness until the negatives were uncovered in Spain and recently restored by Filmoteca de Catalunya, with l’Observatoire, Art et Recherche.

Derkaoui’s film has since assumed cult status among historians, secularists and other film geeks for its footage of swinging Casablanca and Moroccan intellectuals’ engagement with their countrymen about what stories the country’s cinema should be telling.

In anticipation of Derkaoui’s Beirut debut, The Second Encounter will premiere Ali Essafi’s 2020 doc Before the Dying of the Light, which collages posters, magazine covers, archive footage, jazz music, cartoons and other shards of 1970s Morocco with stories of the country’s artists — many of whom were imprisoned or disappeared — recollecting an era of enthusiasm in the future, not yet crushed by state repression.

A still from Ali Essafi’s 2020 essay film ‘Before the Dying of the Light.’ (Courtesy Metropolis)

A still from Ali Essafi’s 2020 essay film ‘Before the Dying of the Light.’ (Courtesy Metropolis)

A filmmaker’s work and its restoration

Born and raised in Beirut, Jocelyne Saab (1948-2019) studied political economy in the city and at Paris’ Sorbonne. She worked in Lebanese radio before remaking herself as a journalist and documentary filmmaker.

Saab covered a region from the Western Sahara to Iran and beyond, with much of her journalism broadcast on French television. She is best remembered for her work on the Palestinian revolution — her career overlapped with those of several international filmmakers engaged with that struggle, and some stylistic similarities have been noted — and the Lebanese Civil War.

Her first longer documentary, Lebanon in a Whirlwind, is a pre-war survey of the political and social forces swirling through a country on the brink of a 15-year-long conflict. Whirlwind is among 12 newly restored Saab documentaries from 1974-1982 that are at the center of The Second Encounter.

Association Jocelyne Saab (AJS) head Mathilde Rouxel wanted to hitch the restoration of Saab’s works to the creation of a training program in digital film restoration for young Lebanese.

“The idea was to create an infrastructure in the country that eventually will allow digital restorations here. It’s not the usual restoration process,” Ouayda says. “It started in 2020. In July, 2021, we collaborated on a workshop, a sort of first installment of that training in Beirut with ThePostOffice’s Mahmoud Korek. There were three or four participants that continued working on the restoration, plus some people in Marseille, Paris, and San Sebastian.”

Jocelyne Saab in a still from her 1982 doc ‘Beirut, My City.’ (Courtesy Metropolis)

Jocelyne Saab in a still from her 1982 doc ‘Beirut, My City.’ (Courtesy Metropolis)

Film restoration embraces a broad discipline that ranges from quite expensive analogue practices (physically cleaning prints and negatives, for instance) to simple, less costly, digitization of prints. Ouayda says AJS’s is a digital restoration with an eye to authentic exhibition quality.

“The thing with restoration is that you start working on the image itself. So if there are any scratches, tears, or discolorations — sometimes the film goes red, for instance — the object is to get as close as possible to a projection of the film at the time it was made. It’s not about cleaning.

“If a print was meant to have a certain grain, say, or if the cuts were made very fast — as a war journalist would have done — the idea is not to erase these cuts. You should keep them because they tell a story about how that film was made and in what context.

“Being trained in [digital] restoration is not just about learning the software. It’s about identifying what kind of film was used, for example, what kinds of hues and tones it had, etc. [The object is not to give it] the aesthetics of cinema today. It’s about balancing ethical questions about how much we’re manipulating and what we’re doing with that material.”

The restorations of Saab’s work will reveal much about the conditions in which she practiced — specifically edits that departed from the original cut of individual films.

“Because Jocelyne was a journalist, she would send her work to TV companies and, depending on which company and where it was, she would do different versions. There are English versions. There are French versions. There are Arabic versions, and sometimes they don’t match.”

These variations also influence programming choices.

For “some of the films,” Ouayda says, “there was a whole discussion about which version to show. Should we show them with the English voiceover, or with the French voiceover?”

Still from Jocelyne Saab’s 1974 ‘Lebanon in a Whirlwind.’ (Courtesy Metropolis)

Still from Jocelyne Saab’s 1974 ‘Lebanon in a Whirlwind.’ (Courtesy Metropolis)

Whither Lebanon’s film archive?

In 2002, the artist-filmmaking duo Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige released a short titled The Lost Film. Early in the film, they take their camera into the Lebanese ministry of culture’s National Film Library (Cinémathèque Nationale du Liban), where they find a scene of depleted chaos. The sequence confirmed common perceptions of an undernourished state’s attitude to the cultural legacy of its artists.

Ouayda doesn’t dispute the footage, but she’s ambivalent about what it means.

“The library was actually Jocelyne’s initiative,” she says, “a project she founded and insisted be administered by the ministry of culture.

“I try not to just perpetuate this idea that we have no archives because it is true, but also not true. There are archives — some of them are accessible, some aren’t — but the fact is that there are no real cultural policies in place that allow us to protect such an archive. The Cinematheque National has a lot of paper archives and researchers have found very important documents there. It’s more complex than ‘Nothing is there. It’s complete chaos.’

Discussion after the screening of Syrian filmmaker Nabil Maleh’s 1972 feature ‘The Leopard’ at Beirut’s Arab Film Club, the subject of a talk by Anaïs Farine. (Courtesy Cinémathèque Nationale du Liban)

Discussion after the screening of Syrian filmmaker Nabil Maleh’s 1972 feature ‘The Leopard’ at Beirut’s Arab Film Club, the subject of a talk by Anaïs Farine. (Courtesy Cinémathèque Nationale du Liban)

“A lot of work has been done to preserve, to catalogue, to research, and disseminate these archives — like the work that UMAM has done with the Baalbak Studios archive and that the Arab Image Foundation has been doing with a lot of different photographic collections. Metropolis’ entry point into archives is through programming. Programming and film exhibition are intimately linked to the writing of history and preservation — not only of the films themselves but also of the audience, of the technologies of the practice of cinema and film culture.”

Ouayda muses that, things being as they are, perhaps it’s not such a bad thing that non-governmental structures and individuals have taken the lead in conserving the archive.

“It allows us to disperse the archive in a way that isn’t so bad, in a country where safety is an issue,” she observes. “Also, if there were any kind of censorship or discrimination against certain archives, that’s less damaging when non-state initiatives have access to the archive.

“That doesn’t mean that this practice should be normalized or that we shouldn’t push for cultural policies. The privatization of these initiatives determines the scale on which we can work. It is a shame. These [public] institutions should be ours.”

She pauses. “But it’s like this discourse about not having a unified history book ... I don’t know. I also like to challenge that a little bit. In France, the Cinematheque Francais dictates what French cinema is — who gets to be in, who’s out. A lot of filmmakers can be excluded from this official history.

“In that sense, maybe it’s okay to not have one official history.”

The Second Encounter’s films and talks will be staged Jan 20-26 at Cinema Montaigne, Institut Français du Liban, Galaxy Cinemas, and Orient Institut Beirut. Physical exhibitions hosted by IF are up Jan. 20- Feb.2