A still shot from "Morphine." (Courtesy of: Hoda Kerbage)

Yehia Jaber stands out among Lebanon’s veteran playwrights. His latest play, “Min Kfarshima Lal Madfoon,” is a third monodrama featuring a female lead, after “Morphine” and the long-running hit “Mjaddrah Hamra.”

There are takeaways from each that are worth comparing, as Jaber’s female-led stories transcend the depiction of women in grief, and the personal becomes political. His plays, like all great pieces of theater, serve as social commentary, with women’s failed marriages serving to frame his political messages. Those messages are bitter, with the plays ending tragically so as to raise uncomfortable truths about Lebanon’s confessionalism and social failures.

The Christian betrayal

In her first leading stage role, Nathalie Naoum, a well-known TV personality from the “S.L. Chi” comedy show, delivered a captivating 90-minute solo performance in "Min Kfarshima lal Madfoun,” where the turmoil of discovering her husband's infidelity becomes an emotional rollercoaster for the audience too.

Playing a Maronite woman married to a powerful Greek Orthodox divorce lawyer, Naoum's character Laura delights in the role of the dutiful wife, who grows resentful of her husband's neglect and her fading beauty. Praising his magnetic charisma, she also sings and dances for him, and tempts him with dishes of shishbarak, evoking sympathy for her naivety.

A still shot from "Min Kfarshima Lal Madfoon." (Courtesy of: Hoda Kerbage)

A still shot from "Min Kfarshima Lal Madfoon." (Courtesy of: Hoda Kerbage)

The stage is sparse, with only a scarf and a chair for props, while Naoum acts out her minimalist existence in the vast empty space. Adopting an exaggerated sectarian dogma, and references to past heroes of Baabda’s Kfarshima like Philemon Wehbi, Melhem Barakat, and Majida El Roumi to accentuate her songs, Jaber holds up a mirror to Christian prejudices still prevalent in those calling for a “federalist” system within Lebanon.

In a dramatic revelation, Laura confronts her philandering husband on the eve of his political inauguration in the “Phoenician Christian Democratic Party.” Initially, her plan is to humiliate him, but when this backfires she is left at the side of the road, turning in circles at the roundabouts of Madfoun, a Christian village whose name translates literally to "buried." Here, she laments the crumbling facade of her marriage, and likens it to the fractured history of Lebanon's Christian sects betraying each other, pointing at the presidential chair that has lost its legs.

In a post-show reflection, Naoum describes Yehia Jaber's storytelling as “the delicate weave of lacework.” When asked why the play is intentionally controversial, her answer is immediate: “We have to put our finger in the wound and expose our faults!”

The Shia murder

Where “Min Kfarshima lal Madfoun” put a mirror to Lebanon’s Christian communities, "Mjaddarah Hamra,” which premiered in 2018, portrays the stories of three distinct Shia women.

The script is also deeply nuanced with classist accents and religious satire, as Jaber is the son of a Muslim Shia sheikh from the village of Wadi Jilo. “I am very Shia, and very communist!” he tells L’Orient Today during one recent performance of the show, in loud, roaring laughter among the throng of the audience.

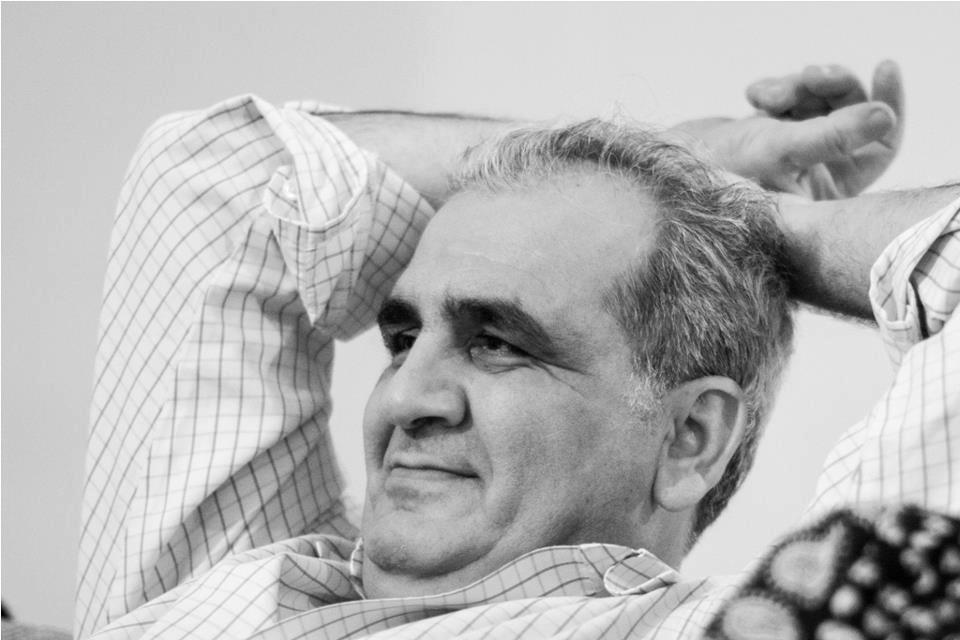

Playwright Yehia Jaber.

Playwright Yehia Jaber.

Against a backdrop of three sofa chairs, actress Anjo Rihane deftly transitions between characters using only her skirt and seating spot, bringing to life the stories of Mariam, a French expatriate; Fatam, a widow yearning for remarriage; and Souad, a woman testifying to her husband’s abuse.

Each character in “Mjaddarah Hamra” represents a divergent experience of marital problems. Mariam, the refined Parisian divorcee, grapples with conflicted emotions for her ex-husband and childhood lover, while Fatam seeks solace in the gossip of her neighbors as she navigates the struggles of widowhood and remarriage. Meanwhile, Souad's story depicts the common trope of the young bride married off in an abusive marriage, culminating in a shocking revelation of her decision to poison her husband through a dish of mjaddara hamra.

Ultimately, the weakest of the characters ends up with the most agency, and surprises the audience with her ascent to freedom. In this way, Jaber juxtaposes educated and uneducated women to deliver his political message, which echoes in his call for the poor to “eat the rich.”

The Palestinian tragedy

In the middle of the trilogy is "Morphine," an autofictional journey written as a collaborative effort between Jaber and actress Sawsan Chawraba in 2022.

Unlike the minimalist staging of his other plays, "Morphine" features embellished decor, including a piano and a plush armchair befitting the refined persona of Chawraba's cultured and extravagant aunt.

With a fanciful Palestinian accent acquired from her second husband, her character Aunt Souhair veers between moments of perfect piano playing and wild outbursts, taking the audience on a ride through the highs and lows of her adopted Palestinian identity, caught between a glorious past and modern ruin. Her stories about asking her “friend” Queen Elizabeth to influence Lord Balfour to share land with the Palestinians is delivered with such hallucination that the audience can’t help but laugh.

From her affluent days mingling with luminaries to her present-day tragedy, Chawraba’s aunt represents the Palestinian diaspora’s dilemma. Reminded of one failed marriage after another, her life story crescendos into a thunderous reality check, where she confronts her cancer and dependency on her family’s charity as her only lifeline. She is left unable to rise above her pity, slips back into her victimhood, and leaves the stage searching for her morphine and refuge. Jaber’s conclusion leaves a bleak outlook for the Palestinian resistance and nostalgia for its rich cultural contribution.

The Feminist lens

Jaber’s plays fearlessly expose Lebanon's socio-political vulnerabilities — a daring subject matter in this uncertain present. Without mentioning a specific time and date, we know the plays are set post-Civil War, but there is no reference to the modern economic and political timeframe. It could be today or it could be in the early 2000s. This is a reflection that little has changed in terms of social evolution since then.

Yet, at the surface of Jaber’s storytelling are aged entertainment gimmicks like encouraging the audience to clap for dances, and tongue-in-cheek irony that plays on double meanings and presents his heroines as clowns.

“Song and dance is necessary for the stage, so that the audience feels the merriment of theater! Otherwise how would they sit through a 90 minute monologue?” Jaber retaliates. Equally, his monodrama plays such as “Shoo..haaa” and “Beirut above the tree” also feature male leads performing song and dance interludes.

While Yehia Jaber adeptly channels the power of political satire, it is the actresses who truly give their characters depth and authenticity.

What sets Jaber's heroines apart is their ability to give depth to the innermost feelings and thoughts of vastly different characters grappling with the damage of repression and injustice. Their ability to embody the essence of womanhood amid societal limitations is what elevates Jaber's work to a feminist narrative.

In conversation with Jaber, his disillusionment with Lebanon's sectarian divide is palpable, yet his commitment to shedding light on the nation's vulnerabilities remains unwavering. “Why have these shocks left us so traumatized that we’re unable to express what is happening to us? We need to confess to our failures, our faults, our history, our pain, we can’t always be the winners. Being a member of a political party is supposed to be the most honorable contribution, but in Lebanon we’ve reduced it to contempt,” he gruffs.

“As an artist who is questioning everything, contradicting everything, I go to the most dangerous topics. Controversy doesn’t scare me, and censorship doesn’t hold me back. That is why my next play is on the topic of gender through the frame of a communist-party household, where the major conflict is what a woman decides to wear. It’s ideologically an old debate, and we are still confronting the same issues!”

Jaber’s next play is entitled “Shu Mnilbos” translating to ‘What do we wear?’, and features Anjo Rihane again taking on the role of three women, and will premiere at Al Madina Theater on March 27. Another of his plays, “Haykaloo” starring Abbas Jaafar, is also showing at Al Medina Theater this month on March 28.

Going back to the topic of feminism, Jaber concludes philosophically, “I would like to be a free and liberated man, but I know that would never happen without women being free, too. Unliberated women also hold men back.”

Yehia Jaber's artistic voice is a testament to his love of the human spirit and the power of art to illuminate the darkest corners of society. As Lebanon continues to grapple with its demons, Jaber’s work perhaps gives some guiding light, even if it does seem outdated, in offering solace to a nation in search of unifying justice.