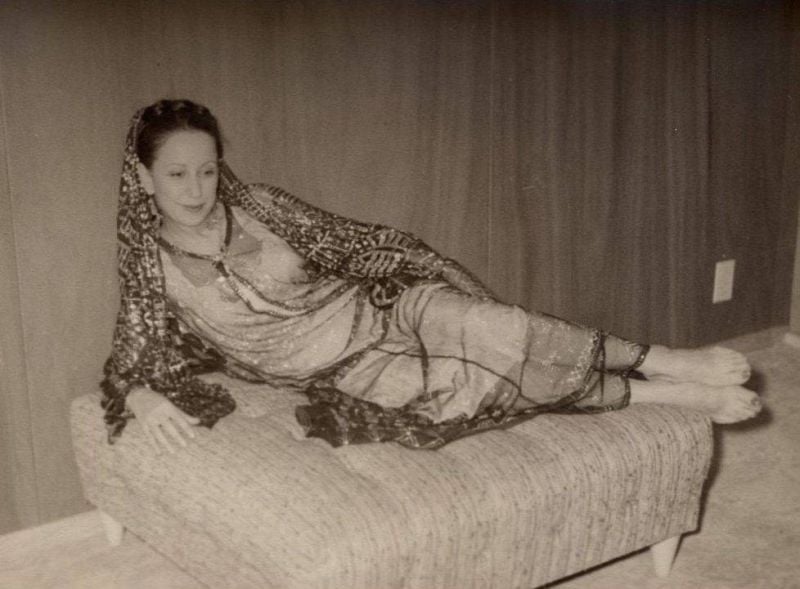

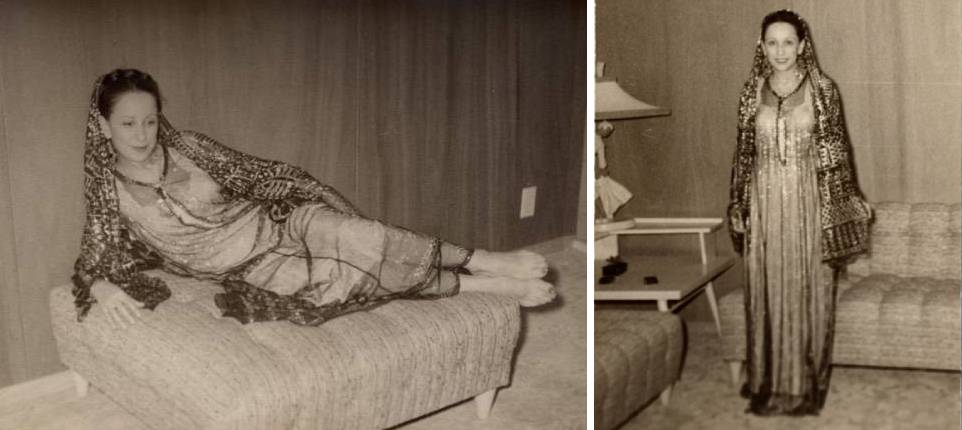

This photo hung at the ACCESS Main building. Its label read, "A lighter side of fun-loving and spirited Aliya is shown here as she dances in an Egyptian dress." (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

BEIRUT — Activist, poet, community organizer, dancer, private investigator, friend of Malcolm X, dubbed “Mother of Arabs” by the diaspora community in the United States — someone with a life punctuated by such an array of accolades and adventures might be expected to be part of Arabs’ collective consciousness alongside diaspora cultural icons like Edward Said, Etel Adnan and Gibran Khalil Gibran.

But somehow, despite her dynamic and impactful life, Aliya Ogdie Hassen never became a household name beyond the Arab-American community of Dearborn and Detroit, Michigan. How is this possible?

“The reasons are manyfold,” says Edward Curtis, himself a third-generation Syrian immigrant to the US — and a descendent of Ernest Hamwi, often credited as the inventor of the ice-cream cone — who, in his book Muslims of the Heartland, uncovers the surprisingly long history of Muslims in the American Midwest. Hassen’s life was so crucial to the story that he dedicated an entire chapter to her.

First, Curtis says, the historical context played a role. While some Arab immigrants made their way to the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth century — among them Hassen’s parents, who came from present-day Lebanon — their numbers were small because official discrimination against people not from northwestern Europe was codified in US immigration law. In 1965, the Hart-Celler Act was passed, which finally did away with national quotas; after that, many new Muslims immigrated to the US, of whom only some were from the Arab world, while larger numbers came from Europe and East Asia.

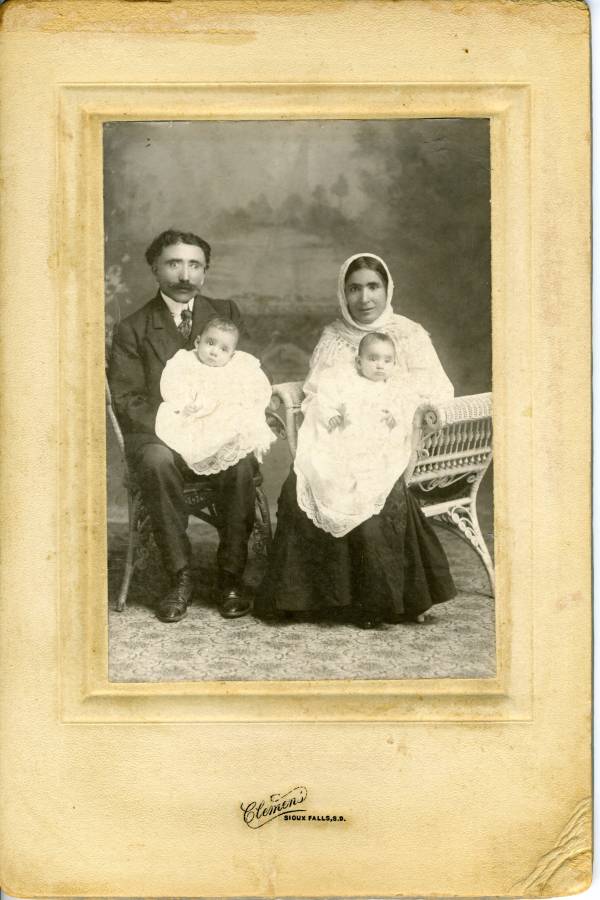

This photo hung at the old ACCESS Main building. “Aliya was born in Kadoka, South Dakota, in 1910. Her parents were among the first Lebanese Muslims to arrive in America. This photograph depicts Aliya (right) with her parents and a brother." This picture was taken in 1910. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

This photo hung at the old ACCESS Main building. “Aliya was born in Kadoka, South Dakota, in 1910. Her parents were among the first Lebanese Muslims to arrive in America. This photograph depicts Aliya (right) with her parents and a brother." This picture was taken in 1910. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

The newcomers established “literally hundreds of new mosques in just a couple of decades,” Curtis says. “In some cases … when they meet the old Arab Muslims, they’re very critical of them. Because these old Arab Muslims, they had developed their own traditions by this time, since they had been here since the 1880s,” combining their Muslim, Arab and American identities. However, he said, the new wave of immigrants criticized the old Arab Muslims for not practicing the “right Islam.”

“I mean, they were playing bingo in the mosque! There’s nothing more American than playing bingo in your religious congregation, no matter the religion,” Curtis says. “And these old Arab Muslims were seen by the new wave of immigrants as so assimilated into American culture that they were no longer Arabs. For instance, they were very critical of the gender relations among Arab-American Muslims.”

In this context, Aliya stood out like a sore thumb. She was born Aliya Ogdie (Hassen was her married name) in 1910 in Sioux Falls, South Dakota to Shiite Muslim parents Ali and Fatima from Qaraoun in what was then Syria but is today Lebanon. She went to live with her aunt and uncle, Fatima and Mohammed Ogdie in a working class neighborhood in Dearborn, Michigan where she enrolled in the Briggs School for Girls.

However, shortly after, her mother arranged a marriage for then-15-year-old Hassen to a fellow Syrian Muslim immigrant, with whom she had a daughter. As a married teenager, she wrote precocious poetry, which, while unpublished, offered a glimpse into her early feminist ruminations.

In a poem describing her wedding night, Hassen lamented that her marital night did not revolve around love and romance, but around her husband’s own insecurity and his domination of her: “While I into the bridal chamber / went, compared with you a babe / In my innocence you reveled / As with a new toy / And in my stark terror / Never once pitied my plight.”

Showing her fierce independence and unwillingness to adhere to the stifling patriarchal societal norms of that era, she divorced her husband in an American court in 1932, citing “extreme cruelty” and married a white Christian less than a month later — but the couple soon separated. Thomas Simsarian Dolan wrote in a 2020 edition of the “Mashriq & Majar” journal that Aliya’s grandson Ismael Ahmed “speculates she may have wanted to disavow this interfaith union — consecrated by a priest — after she became a hajjah in the 1970s,” just as she may have hoped to obscure the fact that the couple likely bonded over their shared penchant for gambling. She would later marry a third time, to Egyptian merchant mariner Ali Hassen in the early 1950s.

In Detroit, Curtis writes, Aliya Hassen was poor, but felt free to live the life that she had dreamed about. She started frequenting speakeasies, “drinking and dancing until the wee hours,” and became what she described as “movie mad,” going to the cinema despite having to hold down three jobs just to get by. However, she refused to seek aid from a nearby soup kitchen or to take any other public assistance.

Dolan writes that the highlights of Hassen’s life included national publication of excerpts of her 76,000-word work, The Crescent and the Cross or The Torch of Islam, which he says offers a critique of “the widespread misinformation and circular citational practices that typify Western discourse on Islam” and traveling as a guest of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, as well as a close friendship with Malcolm X and a plethora of other multiracial Muslims across the twentieth century.

Aliya Hassen with Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt in 1961 when Nasser hosted the annual convention of the FIA (Federation of Islamic Associations in the US and Canada). Hassen was its second vice president. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

Aliya Hassen with Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt in 1961 when Nasser hosted the annual convention of the FIA (Federation of Islamic Associations in the US and Canada). Hassen was its second vice president. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

Hassen’s relationship with the Nation of Islam had a shaky start. Her paper “What Is an Orthodox Muslim?” in which she painstakingly explores similarities among the three Abrahamic religions, scrutinizes “the birth of at least three very un-Islamic religious sects [in the United States], who have used the name of Islam for their self-aggrandizement [sic] … The press, the radio and the television, have given at least one of these sects so much publicity that the average American no longer knows the difference between a ‘Green Muslim,’ a ‘White Muslim,’ a ‘Black Muslim,’ a ‘Heretical Muslim,’ or an ‘Orthodox Muslim.’”

However, according to Dolan, Hassen’s scrutiny of the Nation of Islam ultimately led to a friendship with Malcolm X, which Hassen often cited as one of the most important of her life.

“Although the archival evidence for their relationship is often faint, it challenges racialized, gendered, and ageist assumptions about Civil Rights activism — and establishes solidarities and moral geographies essential to Hassen’s, if not Malcolm’s, work,” Dolan writes.

Hassen described in her writings first meeting Malcolm when he personally intervened to get her into a sold-out Nation of Islam lecture in Harlem after she was denied entrance because of her race. In Malcolm X’s own correspondence, he referred to Hassen as a “friend” in 1961, while Hassen reported that she helped plan Malcolm’s hajj pilgrimage. And although Hassen would not complete her own hajj until 1975, Malcolm X’s wife, Betty Shabazz, sent Hassen a postcard from Mecca thanking her for help and introductions during Betty’s hajj in 1965, just after her husband was assassinated.

Moving to New York after World War II, Curtis writes, Hassen also emerged as a leading intellectual figure in the Federation of Islamic Associations in the United States and Canada (FIA), writing pioneering popular scholarship on Muslim women’s history for the FIA Journal. She also worked to further “interracial, international, and interethnic solidarity among Muslims in the United States and abroad.” During her New York years, she also worked as a private detective.

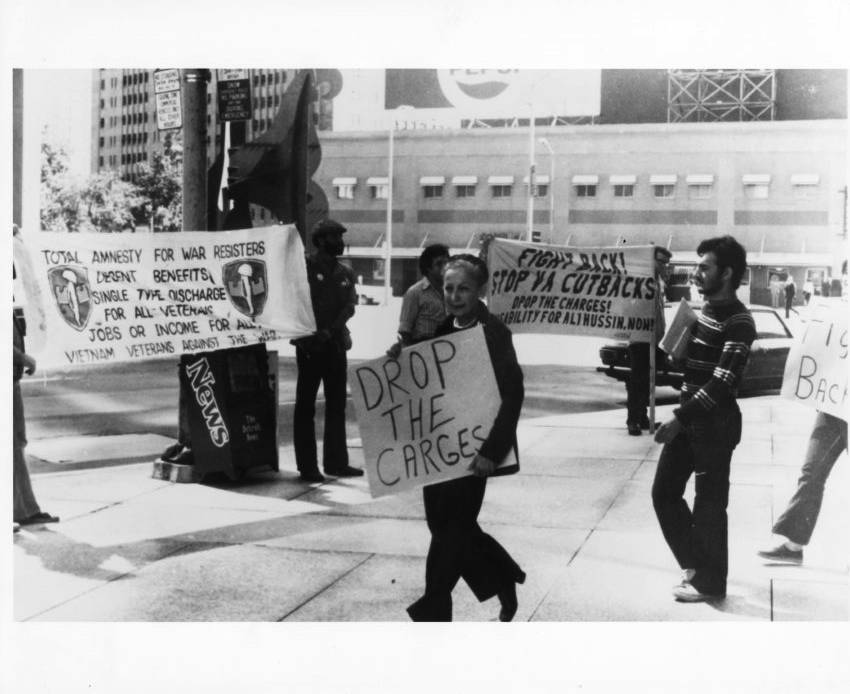

"Aliya demonstrating with Vietnam War Veterans about the conditions of veteran hospitals" in the 1960s. She holds a sign that reads, "Drop the [Charges]." Another sign behind her reads, “Fight Back! Stop VA Cutbacks. Drop the Charges! Disability for Ali Hussin now!" (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)She would even spend her “retirement” as founding director of Detroit’s Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS), which was created in 1971 out of a storefront in Dearborn’s impoverished south end to assist the Arab immigrant population to adapt to life in the United States. Today, ACCESS is the largest Arab-American community nonprofit in the United States.

"Aliya demonstrating with Vietnam War Veterans about the conditions of veteran hospitals" in the 1960s. She holds a sign that reads, "Drop the [Charges]." Another sign behind her reads, “Fight Back! Stop VA Cutbacks. Drop the Charges! Disability for Ali Hussin now!" (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)She would even spend her “retirement” as founding director of Detroit’s Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS), which was created in 1971 out of a storefront in Dearborn’s impoverished south end to assist the Arab immigrant population to adapt to life in the United States. Today, ACCESS is the largest Arab-American community nonprofit in the United States.

She enjoyed local, if not national, renown to the extent that she became known as the “Mother of the Arabs,” according to Dolan.

Moreover, Dolan writes, Hassen’s writing and biography center the United States as a hub of Arab and Muslim organizing in the postwar period, intimately connected to both foreign and domestic civil rights struggles: “By foregrounding religion, Hassen produced solidarities among White, Black, Arab, and Asian Muslims, thereby challenging American racial formations and even national boundaries as salient categories of analysis and affiliation.”

What made Hassen’s community activism unique is that she characterized Islam as a “vibrant and internally contested American religion,” an insight Dolan attributes to Hassen’s former colleague, Sally Howell.

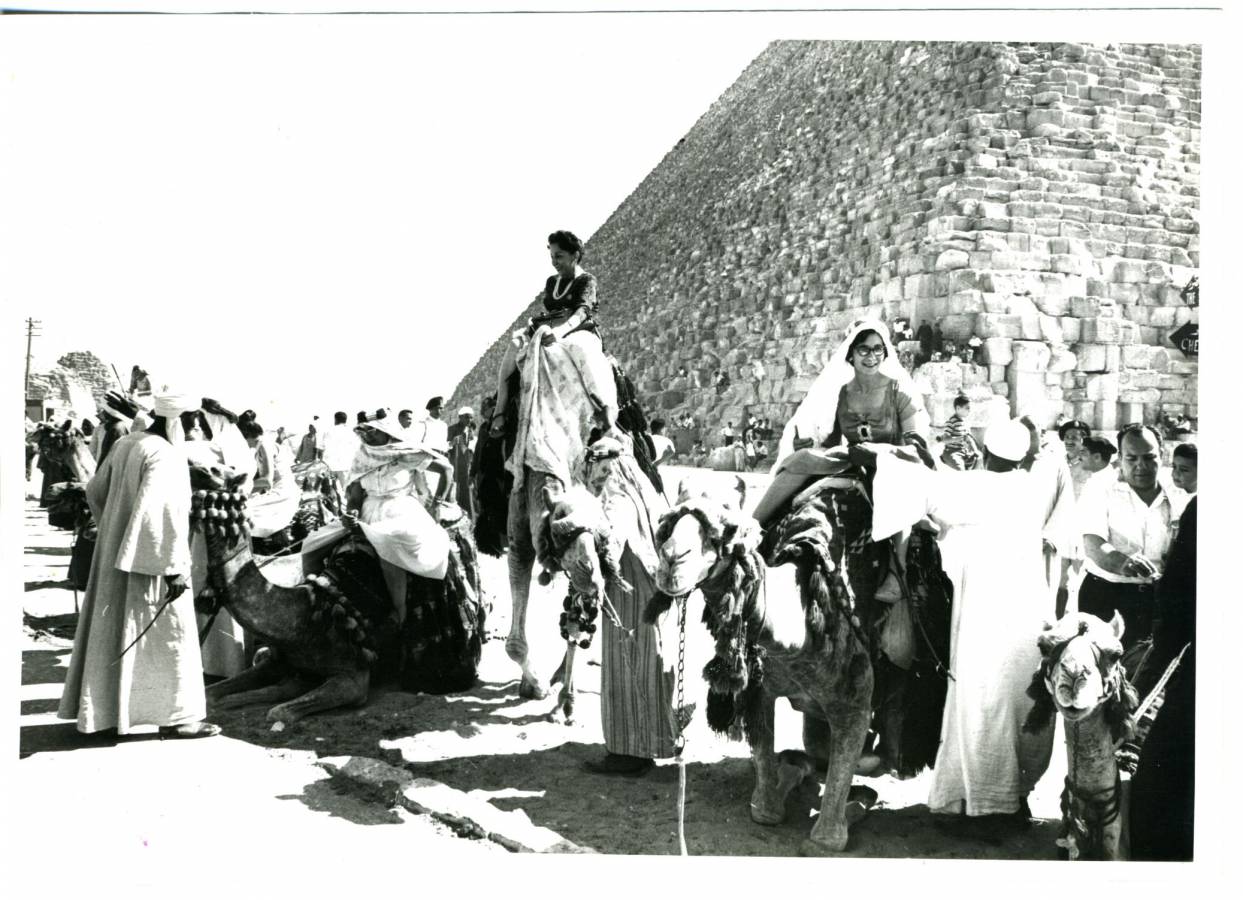

Aliya Hassen on a standing camel in front of the Pyramids of Giza, possibly from the same trip to Egypt as the photograph with Gamal Abdel Nasser. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

Aliya Hassen on a standing camel in front of the Pyramids of Giza, possibly from the same trip to Egypt as the photograph with Gamal Abdel Nasser. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

However, this did not mean that she conformed to Western hegemony, on the contrary, she “linked the economic, political, and epistemic exploitation of the Middle East to Western mythmaking, and voiced this critique through an antiracist and feminist lens squarely situated within Islamic and American ideals,” Dolan wrote — an approach that can be seen as a precursor of what is now firmly established as Third World feminism.

However, today her fame remains confined to the circles of predominantly US academia and the Arab-American communities in which she lived.

Curtis discovered her story because both scholars and community members credited her for co-founding ACCESS, and at the Arab American National Museum, “one of the first people you see is her portrait,” but beyond those circles, she is hardly a household name.

“I think one of the reasons for this is because she is both religious and progressive. She’s Arab and Muslim. She’s all of these things. And she’s also supportive of Black liberation,” Curtis says. “She does not fit the stereotyped version of a Muslim woman in need of salvation.”

“In fact, she saved herself because she didn’t want people to save her,” he adds. “Especially white people.”

It’s a phenomenon that many Arab women, and Muslim women in particular, in the diaspora struggle with: white feminists, led by a white savior complex, often favor those who rage against their culture and are willing to turn their back on it, while their own community might find fault with them if they don’t subscribe to their idea of what an Arab Muslim should be. Pakistani-American Rafia Zakaria, in her book Against White Feminism, argues that Western feminism is shaped by the dominant priorities of white women, critiquing “the colonial thesis that all reform comes from the West,” including the condescension of the white feminist-led “aid industrial complex” and the conflation of sexual liberation as the “sum total of empowerment.”

“She just doesn’t fit the pathological Arab American Muslim woman which is such a powerful trope in American popular culture,” Curtis says. “She’s not a marketable commodity as much but instead provides us with a counter-example. She’s not a cookie cutter Muslim.”

This photo hung at the ACCESS Main building. Its label read, "A lighter side of fun-loving and spirited Aliya is shown here as she dances in an Egyptian dress. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

This photo hung at the ACCESS Main building. Its label read, "A lighter side of fun-loving and spirited Aliya is shown here as she dances in an Egyptian dress. (Courtesy of The Arab American National Museum Collection)

Not only that, Hassen simultaneously became both more normatively religiously observant and inclusive with age, writes Dolan. In her manuscript “Religious Stories for Young Muslims,” Hassen epitomized her universalist point of view, using religion to transcend current iterations of racial and geopolitical difference: “It does not matter to God in the least what your color or nationality is. Your parents may be Africans, Arabs, Chinese, Russians, Americans, or they may be of any race … He created you, white, brown, yellow, red or Black and loves you just as you are.”

“From a European enlightenment perspective, religion is oftentimes associated with closed-mindedness, emotionalism versus rationality, which is why they tried to limit the public role of religion,” Curtis says. “… But religion can also have the opposite effect. In many people that is, the more that they studied their religion, the more that they engaged in a spiritual life of some kind, the actual more loving, more accepting and more big-hearted they become. And clearly, in Aliya’s case, her becoming more spiritual coincided with her becoming even more loving.”

Hassen’s complexity may make her difficult to sell to a mass audience, but Curtis said, “In an age which is ever more parochial where people are trying to narrow their identification with other groups, she is someone that I would love for more people to know about.”