A view of the Karantina neighborhood near the Beirut port, shortly after the blast in August 2020. (L'Orient Today/João Sousa)

Two years after the port blast, and as Lebanon continues to sink under the weight of its compounded political, economic, financial and health crises, Beirutis — particularly those who lost homes and loved ones — struggle to emerge from the devastating experience, and the city remains severely bruised.

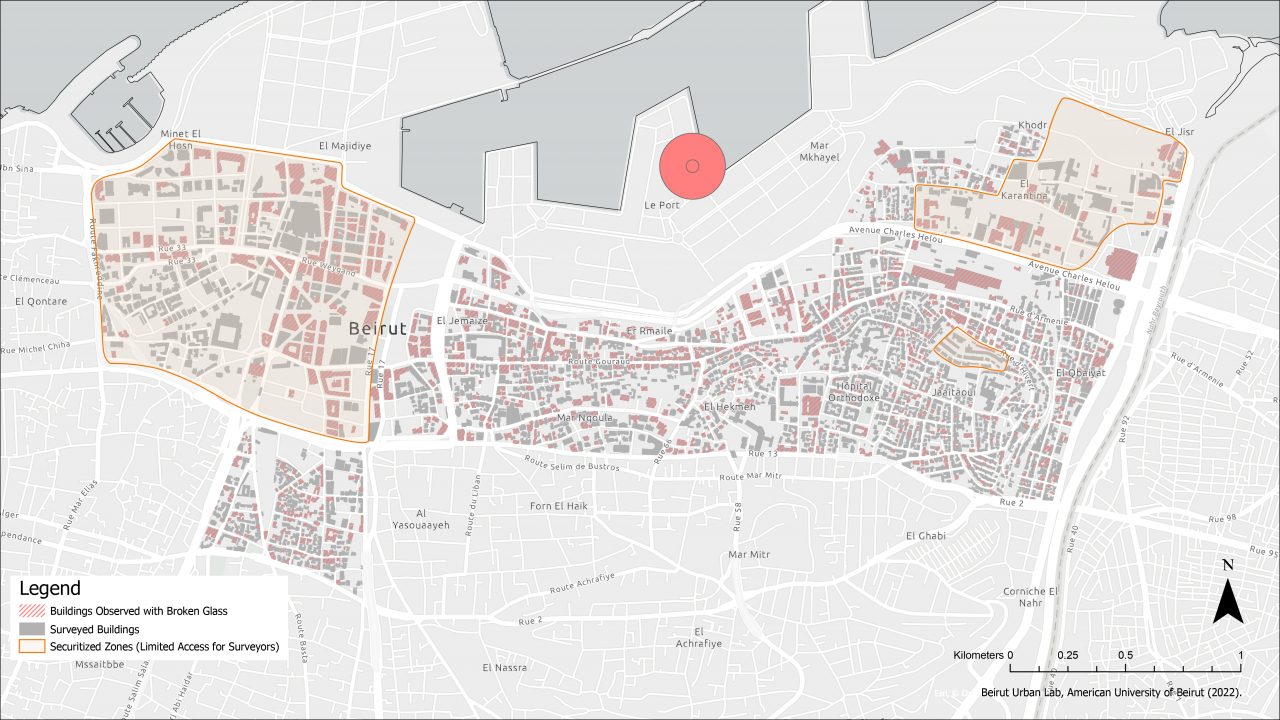

Surveys conducted by the Beirut Urban Lab estimate that a third of Beirut’s apartments in all neighborhoods that were labeled as “severely affected by the blast” are uninhabited and that several city blocks remain fully unrepaired. Not surprisingly, the slowest repairs were found in the historic core where pre-blast (2019) surveys had already shown more than half the apartments to be vacant and unfurnished, and where, to date, numerous blocks display broken windows and doors.

Reflecting on the planning framework in which post-disaster responses have unfolded, it is evident that the subdued role of public agencies has strongly scarred the recovery. Indeed, the absence of these expected custodians of the recovery process led to weak coordination, lack of accountability and trust in repairs, and the prioritization of individual household strategies over collective ones. Ultimately, the blast and its responses have mostly exacerbated pre-existing conditions of precarity and inequity, and consolidated some of the most severe threats facing the city and its dwellers, such as forced residential displacements, the dismantlement of local economies and the loss of communal heritage and collective histories. This can be seen in at least three ways: widening social disparities, exacerbated vulnerabilities, and weakened collective practices.

First, the disaster and its aftermath have widened social disparities. Residents were unequal in facing the explosion’s impacts. Aside from the obvious determinants of geographic proximity, those who lived in more dilapidated homes incurred harsher consequences as flimsy walls and ad-hoc additions (e.g., windows, roofs) crumbled in areas relatively far from the blast’s epicenter. Since poorer structures are typically inhabited by more vulnerable individuals, it is safe to assume that despite widely distributed impacts, the blast affected more severely those who already faced worse conditions.

Furthermore, most home repairs were conducted in a combination of individual household efforts and NGO support, with about two-thirds of the 400 interviewed households having reported some level of NGO help, according to a BUL Survey in June 2022. However, neither resident households nor NGOs are equal in their resources and capabilities. Migrant workers, refugees and Lebanese households of multiple incomes were faced with the same tasks of securing support and conducting self-repair, irrespective of their means and whether NGOs or public agencies allocated to their neighborhoods considered them eligible for aid. Thus, social, symbolic and financial distinctions were reproduced in the repair processes, with the more destitute typically emerging worse off.

Mirroring this inequity, and left to their own device, NGOs also adopted individual and sometimes uncoordinated repair strategies. For instance, numerous humanitarian international organizations adopted the standards of strict habitability typically adopted in post-disaster areas, such as sealing homes, critical repairs and using limited budgets. Other NGOs were keen on repairing buildings fully, particularly when they had been anchored in the affected neighborhoods for decades before the blast. As a result, the definition of what constituted “repair” differed considerably from one apartment or city block to the other. Within the same neighborhood or building, two units could be labeled “repaired” despite displaying radically different physical and living conditions.

Distinctions in damage and repairs left people uneasy, many of them outraged that neighbors had secured substantial support while they did not. Ultimately, these three levels of inequity widened rifts among neighborhood residents, highlighting the cost of missing coordination and equalization in recovery processes typically expected from public agencies.

A second, potentially serious concern should be raised about the quality of repairs — particularly for structurally affected buildings. Several post-blast surveys were conducted in the aftermath of the blast, some based on direct site visits and others on aerial photography. These surveys presented conflicting results about the identification of buildings with structural damage, leaving residents to speculate about what type of structural consolidation was needed, and how to fund it.

Faced with multiple challenges, it is unclear how residents assessed the structural integrity of the apartments where they reside. Worse, pressured by landlords who wanted to reclaim units on so-called old “rent control,” some rushed to return to homes they knew were unsafe.

Conversely, many NGOs refrained from repairing structural damages due to cost, lack of expertise or both. Ultimately, little if any oversight or checking was conducted to verify structural integrity, and it may well be that many homes were patched without considering underlying structural dangers posed if similar shocks, such as mild earthquakes, were to occur in the future. Given that Beirut is heavily exposed to large-scale disaster events, the lack of oversight and accountability typically expected from public agencies left people forced to scramble with limited means in potentially vulnerable conditions.

Finally, the recovery process lacked an integrated neighborhood- or city-wide vision that could have brought affected communities together. A city is not the sum of its houses. Rather, an integrated conception of residents, spaces, functions and flows is critical for the success of a planning intervention, particularly a recovery process.

As a result, the dissection of the post-blast recovery into individual home repairs, followed by scattered interventions in targeted open spaces, has meant that little or no attention was paid to the collective. In the absence of a communal narrative for recovery, residents were pitted against each other, competing over NGO support. Eventually, rivalry over aid left communities bruised and undermined social relations and collaboration among residents. These trends will have long-term negative consequences for the city and its recovery.

In closing, Beirut’s residents continue to pay the hefty cost of their poor urban governance. Their experiences demonstrate the dire need for a public custodian entrusted with coordinating and securing equity and justice in the city’s planning.

As Lebanon looks towards a next round of municipal elections, the hope is for a new leadership for the city, one that could help draw a hopeful, viable future for Beirut and its residents. An active and invested municipal council may be unable to move mountains alone, but it would certainly be a step in the right direction.

Mona Fawaz is a Professor in Urban Studies and Planning and co-founder of the Beirut Urban Lab at the American University of Beirut.