Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati promised on Jan. 5 that a budget would be submitted within two days. Weeks later, Lebanon is still waiting. (Credit: NNA)

BEIRUT – Nearly two weeks have passed since Prime Minister Najib Mikati asserted that the budget “will be ready in two days” and that an “invitation for a cabinet meeting will immediately follow.”

So far, neither promise has come to pass.

This is the third month of government deadlock, triggered by the probe into the 2020 Beirut port explosion. However, over the weekend, Hezbollah and the Amal Movement announced they were ready to end their boycott of the cabinet, paving the way for the government to convene “to discuss everything related to improving the living conditions of the Lebanese.” While the announcement removes one political barrier to the passage of a budget, the budget proposal itself has not yet been forthcoming.

On Monday, Mikati moved the goal post for the draft's completion, saying that he was working with the ministers to have the budget ready by the end of the week.

Experienced observers might note this is not the first time Mikati has volunteered confusing information. Two months ago, on Nov. 9, he announced that Lazard, the asset management company advising the government, would have an amended financial recovery plan ready by the end of the month and, more importantly, that the government had for the first time provided the International Monetary Fund with a unified total for financial sector losses.

To date, no Lazard plan has emerged and the unified number for financial sector losses has been repeatedly denied by Banque du Liban Governor Riad Salameh, who said that he has yet to deliver the data to the IMF.

The lack of progress on many critical files is jeopardizing the talks and delaying any hoped-for recovery. Alain Bifani, former director general of the Ministry of Finance told L’Orient Today that ”the emerging rhetoric surrounding the 2022 budget is only an afterthought to the government’s failure to address the distribution of financial sector losses.”

“After having failed at that exercise [distribution of losses, it] has turned its attention to the second item on the agenda, not because it wanted to but because it was forced to by the international community,” he said.

After serving as director general for 20 years Bifani resigned in 2020, citing bad crisis management.

Lebanon’s missed opportunity, to secure a much-needed bailout from the IMF in the summer of 2020, has further undermined social and economic conditions. Yet all is not lost. The country retains a second chance to kick-start the recovery process, but only if it can adhere to the fund’s terms. Chief among these is the budget, the building block of sound fiscal policy.

The reality is that, for most of the last 20 years, Lebanon managed to muddle through with minimal financial governance. Now, with the country at the edge of a precipice, the situation begs for a different approach.

For the 2022 budget to be relevant, it must be based on realistic macro and microeconomic frameworks and should incorporate the most recent data into its projections. Publishing the budget will also reveal the new exchange rate to be used for all future official government dealings.

It is still unclear whether these forecasts will reveal a full alignment with the Sayrafa rate or a more gradual devaluation from the initial peg of LL1507.5 to the US dollar. The challenge facing the ministry was confirmed by the Finance Ministry's Acting Director General, George Marawi, who said that “[Determining] the exchange rate is the most critical and challenging task currently facing the ministry of finance,” adding that “the budget draft will be ready by the end of next week or by the end of the month at the latest.”

Bifani is more skeptical about the timeline. He points to the recent incident surrounding the release of a memo by Louay EL Hajj Chehade, the revenue director at the Ministry of Finance. The memo disclosed the decision to start converting the stamp duty on contracts from US dollar denomination to lira at the Sayrafa rate; the finance minister then immediately put the new measure on hold. Bifani says this should be a telling sign of how far the ministry is in finalizing the budget draft.

Nevertheless, the depreciation of the lira has had its toll on the ministries’ work and some ministers are already airing their grievances about the existing gap between the cost of providing ministry services, which are increasingly being priced in fresh US dollars, and the ministries’ allocated budgets, still using the peg of LL1507.5 to the US dollar.

First, it was Public Works and Transport Minister Ali Hamieh who explained during a press conference that, for road maintenance, the budget is short by LL69 billion, with another LL59 billion needed for asphalt and other upgrades. This deficit is the result of the above works only, and doesn’t factor in other obligations.

Then, came the turn of the Telecommunications Minister Johnny Corm, who announced that he will be presenting the finance minister with his ministry’s budget and revealed that just for the telecom operators to break even, tariffs need to readjust six-fold higher, meaning that the exchange rate has to be marked up from LL1507.5 to LL9,000 to the US dollar. He has also been repeatedly warning that the telecom sector is in imminent danger of bankruptcy.

The use of close-to-market data for forecasts is crucial to matching revenues to expenditures, however the government must also demonstrate to the IMF that it is using sound judgement in estimating revenues and in managing expenditures. A balancing act that is vital to the government’s credibility given that all the previous attempts by former administrations have failed to bring down expenses under control.

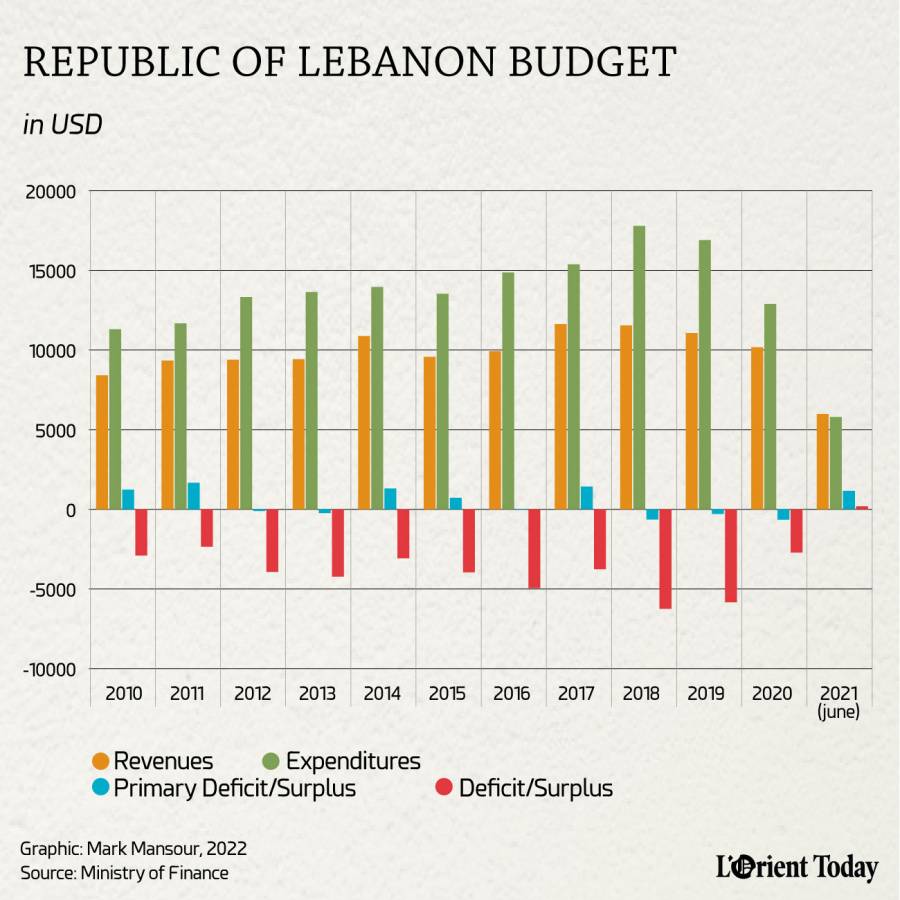

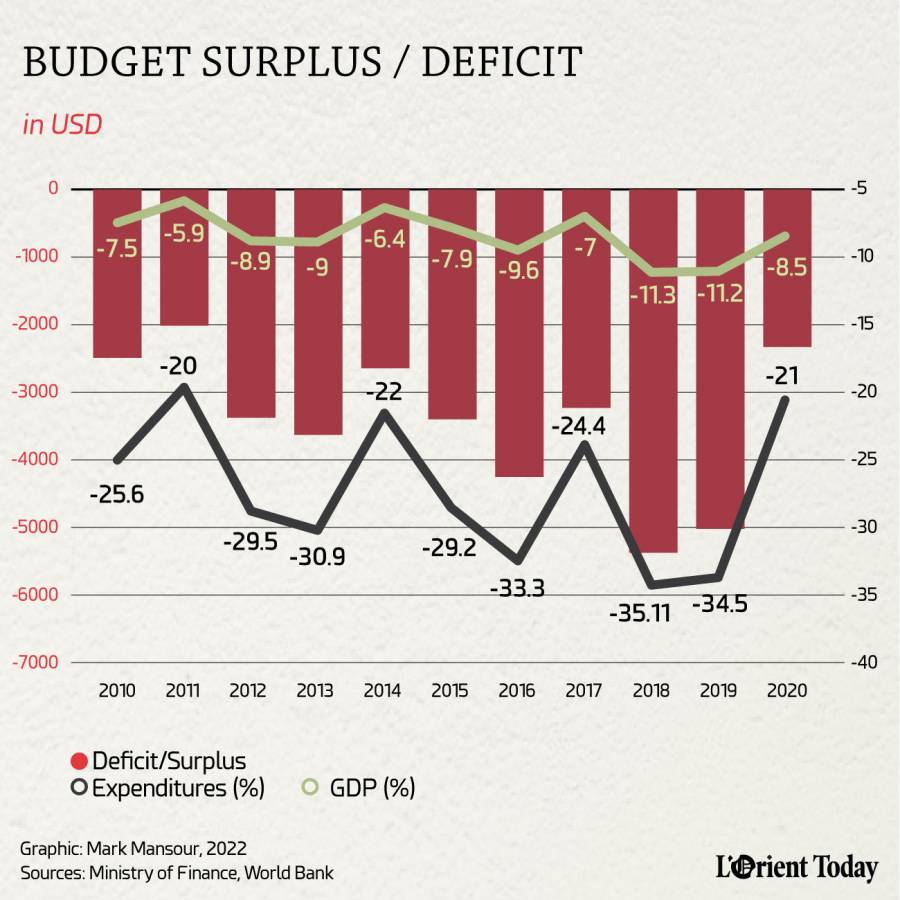

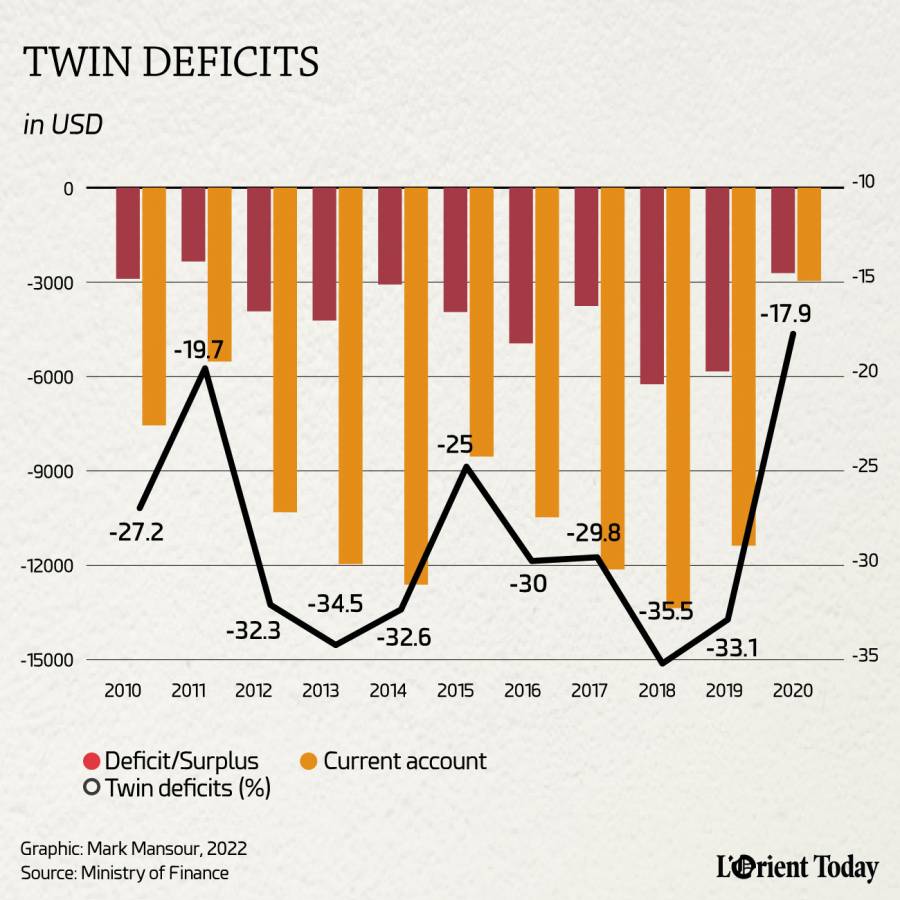

As the data from the last 10 years show, the country’s management of its public finances had little to be desired. The government was spending more than it was bringing in, and the pattern extended back to at least the early 2000s.

Albeit at first, revenues used to cover expenditures thus generating a primary surplus, then interest payments wiped out whatever balance was left, pushing the budget into deficit. But since 2018, this was no longer the case, and revenues were falling short of expenditures.

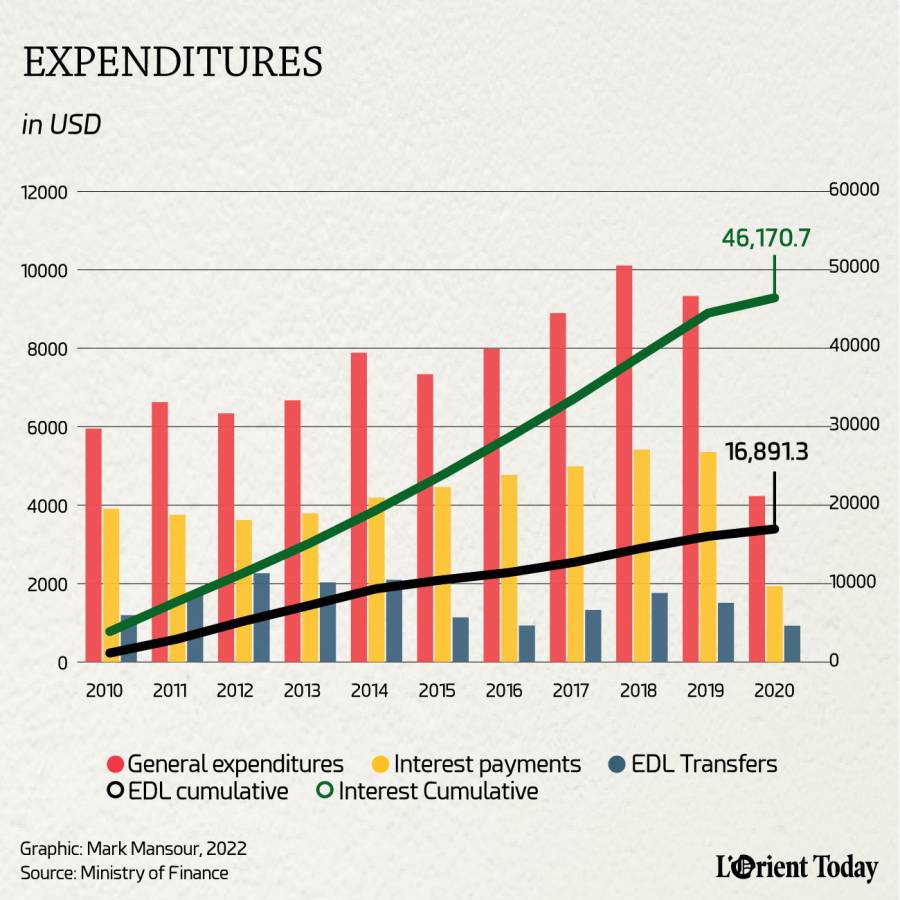

The culprits behind these recurring deficits are none other than a bloated public sector after decades of unchecked hiring, a ballooning debt requiring more and more dollars to service and a dysfunctional national electricity provider, siphoning whatever is left. Ironically interest payments over the last ten years add up to $47 billion, equivalent to Lebanon’s average GDP over the same period. Meaning Lebanese collectively have labored the equivalent of one whole year just to pay off interest.

If Mikati comes through, and the cabinet succeeds in convening to deliver on its ministerial statement is surely welcome news, but Bifani says this is the wrong approach to the wrong problem.

“The piecemeal approach is the problem. The only way out of the crisis is working on a comprehensive plan” but “This is not going to happen. The government doesn’t want reforms, every act of corruption leads back to them, so why would they want reforms.”