A view of the Beirut port prior to the Aug. 4, 2020 port explosion. (Credit: Joseph Barrak/AFP)

BEIRUT — A microcosm of Lebanon, the Beirut port and its most important facility, the container terminal, are trapped in limbo: scarred by the devastating Aug. 4, 2020, explosion; sinking under the weight of the country’s financial and economic collapse; and awaiting overdue decisions on their future, all as foreign powers pursue their interests.

French corporate giant CMA CGM, the world’s third-largest shipping company, hopes to become the operator of the container terminal, replacing the Beirut Container Terminal Company, a consortium formed with the backing of Al-Mawarid Bank chairman Marwan Kheireddine, whose name appears in the recent Pandora Paper leaks.

On Aug. 6 — buried beneath the day’s headlines of cross-border fire between Hezbollah and Israel and government formation efforts — the CEO of CMA CGM met with Lebanon’s president and army chief.

Rodolphe Saadé, the scion of an influential Franco-Lebanese business family with the ear of French presidents, pitched to Michel Aoun his company’s readiness to repair out-of-service cranes at the Port of Beirut container terminal. It was CMA CGM’s latest effort to expand its foothold at the port and the terminal in a campaign bolstered by French diplomacy in Lebanon.

Since last year’s explosion, suitors have come forward offering to rebuild the port, including German firms presenting a wide-scale rebuilding and development proposal, while France’s rival in the eastern Mediterranean, Turkey, has also expressed interest. Key to the port’s future is the container terminal, which generates approximately 75 percent of the facility’s revenues.

Beyond the horizon of public attention but essential for society, maritime transport moves more than 80 percent of goods worldwide. Central to this commerce are standardized containers, in which product transport is concentrated in the hands of the 10 largest shipping companies dominating maritime trade. These shipping giants seek to maximize profits by optimizing shipping routes that hop among container terminals using transshipment.

Since 2004, Beirut port’s then-new terminal has been operated by the Beirut Container Terminal Consortium, a widely praised UK-Lebanese joint venture whose contract came to an end in early 2020. The tender process for a new contract has since stalled, leaving BCTC limping along as the terminal’s operator with rolling three-month contract renewals amid quickly deteriorating conditions at the port.

A source close to decision-making on the bidding said that Premier Najib Mikati’s government is applying “huge pressure” for a tender for the container terminal to be launched soon. CMA CGM — whose owners, the Saadés, have close ties to Lebanon — is the only foreign firm publicly expressing interest in the contract so far, the source said.

With the future of the port and its crown jewel container terminal at a critical turning point, its past offers a guide to understanding its potential significance within Lebanon — for the country’s people and its oligarchs — and internationally for the titans of shipping.

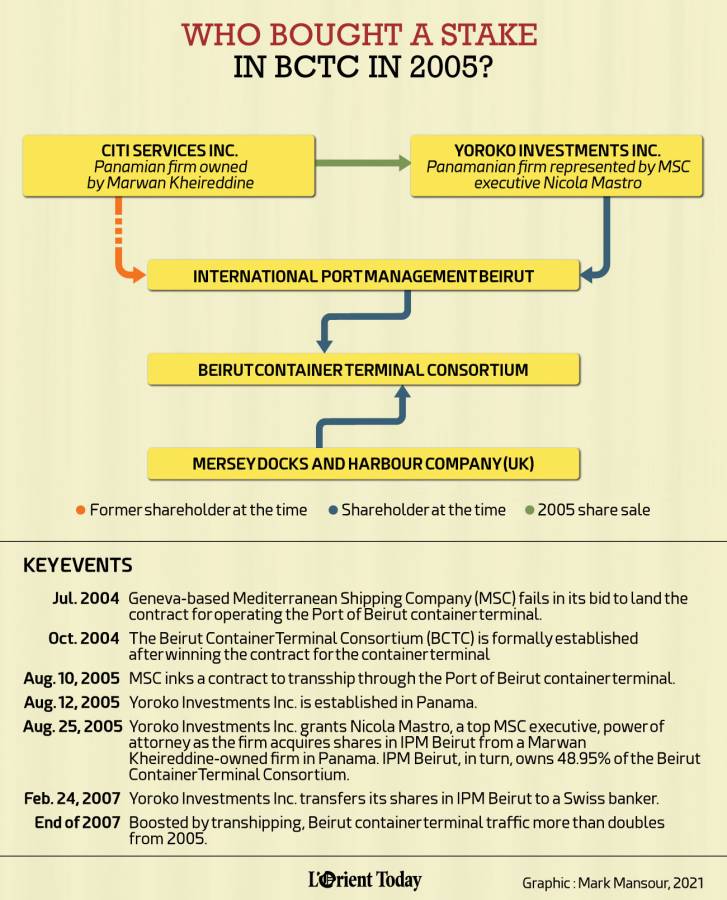

BCTC, the only company to have operated the terminal, encapsulates the local and foreign interests in the port’s container facility. A trail of documents reviewed by L’Orient Today reveals that Kheireddine sold his original stake in the company to a Panamanian front linked to Mediterranean Shipping Company, the world’s second largest shipping outfit. These shares then changed hands from Geneva to Beirut before returning back to Kheireddine.

Like Lebanon, the fate of the Beirut port’s container terminal has been at the mercy of not only domestic political logjams and blurred lines of governance, but also developments and forces beyond the country’s borders and control. Further mirroring the country, years of growth at the terminal — not necessarily benefiting the public at large — have run aground in catastrophe.

Vying for the prize

CMA CGM’s aspirations for the Port of Beirut’s container terminal are not new: in 2004, the French shipping giant fell at the final hurdle of a contentious bidding battle for the prized contract.

The bidding pitted CMA CGM against a number of international firms, including a consortium consisting of a UK port operator and US-based transportation specialists financially backed by Marwan Kheireddine. CMA’s head at the time, Jacques Saadé, a pioneer in the containerized shipping industry, was close to French President Jacques Chirac.

BCTC’s victory over other candidates capped off years of fierce political jockeying — held under the shadow of Syrian tutelage over Lebanon — over the port and its container terminal.

Decisions on the nationally important infrastructure in post-Civil War Lebanon were hammered out away from public scrutiny, including through the Temporary Committee for Management and Investment of the Port of Beirut (known by its French acronym of GEPB), formed in 1993, which became a venue for “frantic horse-trading among leading politicians,” as recounted by Reinoud Leenders in Spoils of Truce.

As political battles on the port dragged on in Lebanon following the end of the Civil War, international shipping was transformed by globalization of markets that spurred a fourfold increase worldwide in containerized shipping between 1990 to 2004. Standardized containers, abbreviated as TEUs, have revolutionized worldwide commerce from their invention in 1956, now accounting for 60 percent of the value of all maritime trade.

Meanwhile, the world’s top 10 largest port operating companies consolidated their dominance over container terminal facilities, handling 67 percent of worldwide container traffic by 2005. That same year, the world’s top 10 shipping lines held just shy of 50 percent of the market’s transport capacity, a trend that has only grown since.

Rafik Hariri, a proponent of neo-liberal policies during his 11 years as premier, backed a contract awarded in 1998 to the Dubai Port Authority to equip and manage a container terminal at the port. DPA exited in 2001, having never launched its operations due in part to obstacles from politically connected subcontractors at the port, according to Leenders.

With the container terminal still unoperational, the GEPB shifted gears in early 2003 to a new plan for the state to bear the cost of equipping the facility and contract its operations to a private firm. A new tender for the container terminal was launched in 2004, with bidding held in July of that year.

The bidding process itself was simple: candidates presented what percentage of the container terminal’s revenues they sought, which were placed in sealed envelopes to be opened in public. The lowest percentage offer from a qualified firm would win.

The bidding, as covered by local media, hit a snafu though. On July 1, when the process began, CMA CGM was granted a daylong extension to provide missing documents for its bid. The GEPB then granted other qualified companies a 10-day extension to amend their bids before a July 12 deadline. This allowed Kheireddine’s consortium to amend its bid from 41.4 percent to 39.6 percent of the terminal’s revenues and overtake CMA CGM’s offer of 40.88 percent, according to The Daily Star.

CMA CGM told L’Orient Today it was not interested in commenting on the past, saying that the “context is different today than in 2004” and that it was focused on the tender process “expected to be launched soon” and the revival of the port.

The GEPB said at the time that the bidding process was handled “in a transparent manner and in compliance with the standards”

“I lobbied with both the US and the UK embassies and asked that their ambassadors be present during the opening of the bids to ensure a proper process. They both attended and I can confirm that there was no foul play in the process,” Kheireddine told L’Orient Today.

Jockeying for the container terminal did not end even after the contract was awarded. Kheireddine said that shortly after his consortium won, he was approached by one of the failed bidders, who he would not name, offering to “buy us all out”; however, he and his partners were not interested in selling at the time.

The winning consortium established BCTC on Oct. 4, 2004. At the time of BCTC’s formation, the new operator of the Port of Beirut container terminal was 51 percent owned by Mersey Docks and Harbour Company, a UK-based port management firm. The conglomerate that now owns MDHC told L’Orient Today that it still holds its stake in BCTC to the present day.

Lebanon-registered International Port Management (IPM) Beirut SAL, in turn, held 48.9 percent of BCTC. Ammar Kanaan, the first CEO of BCTC, told L’Orient Today he was working in the US in the transportation sector prior to the container terminal tender, when he was approached by a Washington-based consultant to join the bidding process.

Kanaan added that he then asked Kheireddine, who he called a long-time friend, to help finance the venture. Corporate documents reviewed by L’Orient Today show that IPM Beirut was owned by a brother-in-law of Kheireddine at the time of the bid. A month after BCTC was formed, IPM Beirut was acquired by a Panamanian company that Kheireddine said he owned.

Kheireddine has a closely intertwined past with Talal Arslan, a politician aligned with Damascus during the Syrian hegemony over Lebanon. Arslan married Kheireddine’s sister in 1993 when they were living in London. In July 2001, Kheireddine — CEO of Al-Mawarid Bank — became one of the founding members of Arslan’s Arab Democratic Party.

In his 2014 study Social Classes and Political Power in Lebanon, Lebanese American University historian Fawwaz Traboulsi argued that Arslan “could preserve his own influence” in the face of rival Druze politician Walid Joumblatt’s financial resources through “relying ever more heavily on the support” of Kheireddine and his bank.

Enter the shipping giants

As BCTC swung into action in late 2004, the port was poised to receive a massive boost from becoming an eastern Mediterranean hub for transshipment, a crucial component of maritime trade. Kheireddine, meanwhile, would go on to sell his stake to foreign buyers in 2005 following initial business losses amid global fuel price increases.

Transshipment is employed by maritime firms seeking to optimize their businesses by transporting containers across the globe on large vessels hopping between hubs, where goods are offloaded onto smaller ships bound for destinations off the main sea routes. From the end of Lebanon’s Civil War until 2005, the percentage of worldwide container trade that is transshipped grew from 18 to 25 percent, all as containerized traffic volumes grew fourfold.

Equipped with a new container terminal, the Port of Beirut, once prosperous before the Civil War, offered an attractive destination for transshipment, according to Jean-Marie Miossec, a geography professor specializing in maritime trade at Université Paul-Valéry in Montpellier, France.

Potentially competing ports along the Turkish, Greek, Cypriot and Syrian coasts at the time suffered from varying issues with efficiency, Miossec said, adding that Beirut benefitted from good infrastructure and BCTC’s management of the container terminal.

On Aug. 10, 2005, Geneva-headquartered Mediterranean Shipping Company — which at the time was the second-largest shipping company in the world with 264 vessels — inked a deal with Beirut port authorities to make the container terminal a transshipment hub for its eastern Mediterranean operations.

Days later, a series of mysterious events kicked off in Panama that point to MSC’s deeper, behind-the scenes involvement in BCTC.

On Aug. 12, 2005, Yoroko Investments Inc. was registered in the secretive offshore jurisdiction. Less than two weeks later, Yoroko Investments Inc. purchased shares in BCTC’s Lebanese parent company from Kheireddine’s Panamanian firm, according to corporate documents reviewed by L’Orient Today.

A tantalizing clue links Yoroko Investments Inc. to MSC: the Panama-registered company granted power of attorney to Nicola Mastro, described by Lloyd’s List in 2010 as one the “central figures behind Mediterranean Shipping Co.’s rapid expansion over the past decade.”

In offshore jurisdictions, such as Panama, power of attorney is one of the tricks of the trade to confer control of a company from its registered directors to the true owner of the firm.

Mastro, who died in 2010, was the “right-hand man” for MSC chair and founder Gianluigi Aponte, according to Lloyd’s List, which said that Mastro had set up MSC’s container terminal operation arm. In 2004, the Swiss-Italian shipping giant failed in its bid to land the Port of Beirut container terminal contract.

MSC and BCTC’s CEO at the time, Ammar Kanaan, declined to comment to L’Orient Today on the matter. BCTC’s press office did not respond to queries.

“I sold my shares in 2005 to a group of investors that were interested in buying me out and that could add value to the business,” Kheireddine said, adding that non-disclosure agreements prevented him from naming them.

“They are strategic investors who invest and understand this business globally,” he said.

While CMA CGM has been able to draw on two generations of deep experience in Lebanon, its rival MSC is no stranger to Lebanon, where it established a subsidiary in May 1996.

That same year, the Lebanese franchise’s co-founder Khairallah Elzein, was an advisor for Yassin Jaber, an Amal-allied politician who served as economy minister under Rafik Hariri from 1995 to 1998.

The businessman was also elected to the Amal Movement’s political bureau in 1992 while a 2011 real estate announcement named him as a representative of the powerful speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri. Zein could not be reached for comment.

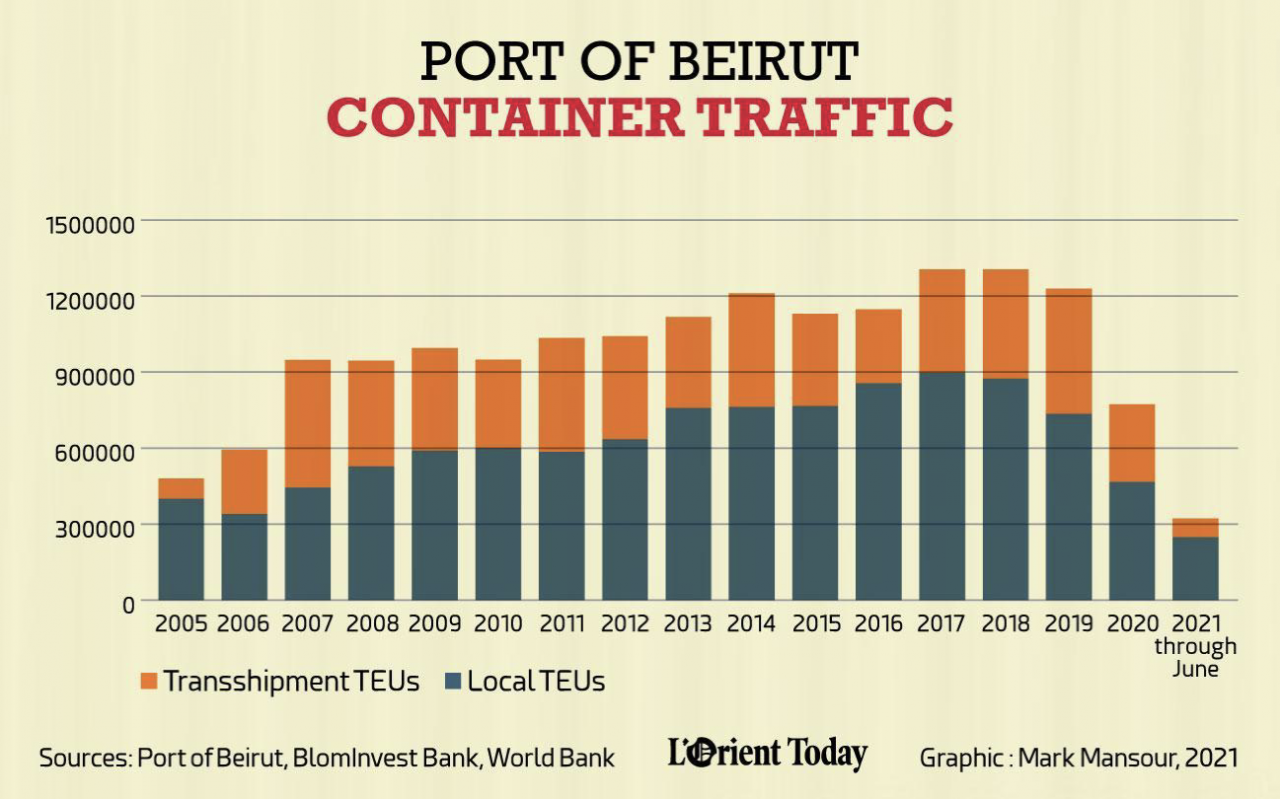

Months after MSC entered the container terminal, CMA CGM signed a transshipment deal for a smaller volume of traffic with the Port of Beirut in 2006. Benefiting from its status as a hub for MSC and CMA CGM, container traffic at the port more than doubled from 2005 to 2007, helping BCTC accrue $2.7 million in profits in 2006 after two years of losses. The stage was set for a decade of growth at the port. Whether these gains benefitted the Lebanese public remains in question.

Fleeting glory

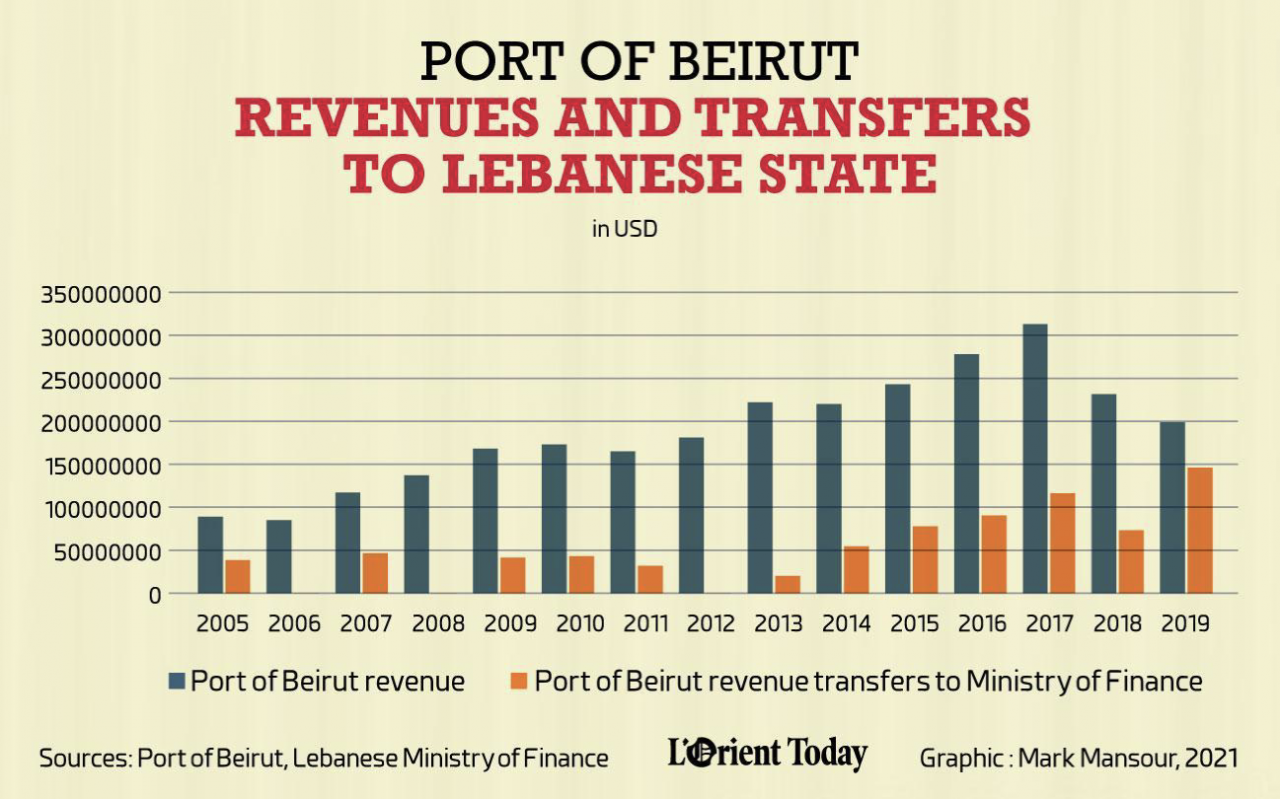

The GEPB says it earned $2.8 billion in revenues from 2005 — when the container terminal that helped generate most of this money went into service — until the end of 2019. These sizable revenues have been under the control of the port authority, widely criticized for its lack of transparency and oversight.

In a scathing report on the Port of Beirut, the World Bank said the temporary committee in charge of the harbor “does not publish balance sheets or financial statements. It is not in itself a legal entity.”

“The absence of a real port authority, coupled with mismanagement by the Temporary Committee have involved serious governance, transparency and accountability issues,” the report added.

Dogged by accusations of corruption and divisions of spoils by Lebanon’s rulers, the GEPB maintains its own private bank account. Between 2005 and 2019, the authority transferred $778.1 million — or 27.6 percent of its revenue — to the Lebanese state, according to Finance Ministry reports reviewed by L’Orient Today.

The Port of Beirut enjoyed success after success, at least at surface level, between 2005 and 2019, thanks in part to factors originating beyond Lebanon’s borders.

MSC and CMA CGM’s use of Beirut as a hub played a major role for increased traffic, and revenues, at the port from 2005 to 2019. The number of containers handled at the port increased almost yearly to a peak of 1.3 million TEUs in 2018, with transshipped ones making up 36.7 percent of total traffic.

Containers unloaded at the port for local consumption began to skyrocket after the Syrian conflict erupted in 2011. The war caused a massive refugee flow into the country, helping swell demand for imports.

Lebanese company BCTC also played a part in bolstering the fortunes of the port through good management of the container terminal. Using its benchmark Logistics Performance Index, the World Bank ranked the container terminal’s productivity as one of the best in the eastern Mediterranean.

As successes mounted at the terminal, the MSC-linked front company that indirectly owned BCTC transferred its shares to a banker in Geneva in early 2007. The financial professional told L’Orient Today that he held these shares as a custodian, but declined to name the true owners.

Ammar Kanaan — who served as CEO of BCTC and now heads MSC’s terminal operating subsidiary — said that other than Kheireddine, no politically affiliated figures held equity stakes in his former company.

Kheireddine, one of the original investors in BCTC, was appointed to Najib Mikati’s cabinet on July 18, 2011, replacing his brother-in-law Talal Arslan, who resigned a month earlier.

Meanwhile, the indirect shares in BCTC held by the Geneva-based banker were acquired by Ammar Kanaan at the end of 2011, before changing hands again to his brother Ziad, another executive at BCTC. The press office for BCTC did not respond to comment.

After 15-years of growing traffic at the port, container handling numbers dipped slightly for 2019. Beneath the surface of the seemingly bullish statistics from this period, the success of the Port of Beirut remains in question.

In particularly harsh language, the World Bank said the Port of Beirut “failed in the key role as an enabler of economic development in the country.”

A week before the start of the Oct. 17, 2019 protests against Lebanon’s political class, with the clock running down on the container terminal’s contract, Kheireddine once again picked up the revolving tranche of indirect shares in BCTC held by its Lebanese parent company, International Port Management Beirut Holding.

“An opportunity presented itself as some of the shareholders of the company wanted to exit around the same time as the contract with the Port of Beirut was expiring,” Kheireddine explained.

“So I grabbed the opportunity and I will be pushing the management team of the company [International Port Management Beirut Holding] to bid on similar port management opportunities worldwide, including in Lebanon,” he said.

What Kherieddine did not know when he again bought into the company was that catastrophe was just around the corner for the Port of Beirut.

A port in crisis

The rocky coasts of the Mediterranean and their growing importance for worldwide trade offer a faint hope to Beirut, a city whose fate has been closely intertwined with its port and international commerce. In the meantime, Lebanon’s woes have been erasing the Beirut port’s container terminal from the map of shipping routes criss-crossing the seas.

Economic collapse in import-heavy Lebanon has led to a sharp decline in traffic at the Port of Beirut. In 2020, the port handled 772,871 TEUs, the first time below 1 million TEUs in a decade. Halfway through 2021, traffic stands at 322,374 TEUs, with transshipments down 63.6 percent from their numbers last June, partially due to MSC suspending its hub operations in Beirut in 2020.

“It’s a slow death,” the CEO of BCTC told our sister publication Le Commerce du Levant in March about the firm’s struggles to maintain operations.

The Aug. 4, 2020 explosion inflicted a tragic human toll, including among people working at the container terminal. The blast, however, did not inflict heavy damage on the infrastructure of the facility. Instead, the financial crisis has left BCTC unable to source the US dollars necessary to maintain and repair key equipment, causing severe repercussions for its operations.

“Container terminal services at the Port of Beirut are going from bad to worse,” the International Chamber of Shipping in Lebanon’s capital warned in a July 9, 2021 statement, urging officials to intervene to help the now-ailing BCTC.

On Sept. 8, the head of the Syndicate of Food Importers warned that a disruption of customs software at the port and a strike at the time by BCTC employees, if unresolved, “portends a major food disaster.”

BCTC continues to manage the container terminal amid these challenging circumstances, 19 months after its contract ended and a new tender was supposed to be issued. In lieu of the new tender being held up in a bureaucratic maze, BCTC’s contract has been renewed on a three-month rolling basis.

In mid-January 2020, the GEPB issued calls for a bid for the container terminal, which attracted a joint candidacy from CMA CGM and MSC as well as ones from UAE-based Gulftainer, China Merchant Ports of Hong Kong, Hutchison Port Holdings and BCTC.

However, then-Transport Minister Michel Najjar subsequently pumped the brakes on the process, referring the tender to Lebanon’s state Tenders Department for review in the Spring.

A source close to the process told L’Orient Today that while the GEPB has worked to address comments from the Tenders Department, the process has been held up by numerous delays.

One of the core issues of formulating the tender, according to the source, is the proposed payment mechanism for firms operating the terminal, with one proposal calling for operators to be paid a fee per handled container in the steadily depreciating Lebanese lira.

If you set the fee in Lebanese lira, no foreign companies other than CMA CGM might come, the source said, while adding that if the container handling fee is in US dollars, the GEPB might have difficulties paying.

The source, who spoke on condition of anonymity, voiced reservations over the wisdom of moving forward with the tender amid an unchecked financial disaster, a sentiment echoed by a United States Agency for International Development report from May 2021 calling for BCTC’s contract to be extended by 18 months.

“Given current uncertainties and the lack of long-term vision and strategic directions for the POB, it is not prudent to make any long-term commitment at this point related to the operations of POB. In this respect, the container terminal's tender should be placed on hold,” the report said.

Jean-Marie Miossec, a geography professor specializing in maritime trade at Université Paul-Valéry in Montpellier, France, pointed out that several factors make the container terminal unattractive for potential suitors, including its small size and infrastructure problems, lack of clear authorities and governance over the Beirut port and the investment risks posed by the collapse of Lebanon’s financial system.

Nevertheless, the Beirut port hitting a low point might entice potential terminal operators eyeing future growth, according to Miossec, who says it will retain importance for trade into the Middle East. The maritime business researcher, who wrote a book chronicling CMA CGM’s history.

French eye Beirut port

CMA CGM’s long-standing interests in Lebanon position it as the foreign firm most interested in pursuing the container terminal contract, according to the anonymous source close to the tender process.

While CMA CGM has repeatedly proclaimed its aspirations for the port, the other firms that entered the tender in early 2020 have remained mum since.

Even MSC, which CMA CGM said in April 2021 was partnering its potential bid for the container terminal, has since grown cold in its interest, according to another source well-connected in the Lebanese maritime sector who said the French was a favorite to land a future contract.

CMA CGM belongs to the Saadé family, who have substantial assets in Lebanon as well as personal ties to their former home countries of Lebanon and Syria. In February 2021, the shipping giant purchased the firm operating the Tripoli container terminal, much smaller than its Beirut counterpart.

”It would be a powerful extension for them to have Tripoli and Beirut,” said the source close to the tender process.

Meanwhile, the Saadé-owned Merit Corporation, CMA CGM’s parent company, holds 4.38 percent of Bank of Beirut, among other investments in the country. Amid collapse in Lebanon, the Saadés re-registered Merit Corporation, moving it from Lebanon to France in early 2021.

France’s ramped up diplomatic efforts in Lebanon after the Aug. 4, 2020 port explosion have aligned with the business interests of CMA CGM, which boasts of its “key role in helping to power the French economy.”

In a July 13, 2021 visit to the port, French official Franck Riester called for launching the stalled tender for the container terminal, warning a failure to resolve its status imperils the port. The French government’s point man for foreign trade met with CMA CGM during his Beirut trip.

In September 2020, CMA CGM CEO Rodolphe Saadé accompanied French President Emmanuel Macron on a visit to Beirut, during which the shipping company unveiled a $400–$600 million plan to repair damage at the port and transform the harbor into a “smart port.”

Following in the footsteps of his father, who was close to former French political heavyweight Jacques Chirac, Rodolphe Saadé knows how to navigate ties with politicians, according to Paris-based La Lettre A. The investigative outlet wrote that Saadé, who has cultivated ties across the political spectrum, has grown closer to Macron, while welcoming figures from the French president’s La République En Marche party to CMA CGM’s tower in central Marseilles.

Macron, for his part, has repeatedly voiced the significance of the Mediterranean for French power projection and pursued diplomacy efforts not only in Lebanon but across the region.

“The 21st century will be a maritime one, this is where power is played out, the geopolitics of tomorrow, that of trade and connections,” Macron said in a Dec. 21, 2019 speech in which he underlined the importance of the Mediterranean.

The Mediterranean Sea is growing in significance for international shipping, according to Miossec, with the geographer explaining that the center of gravity of trade in Europe has shifted with the expansion of the EU and growth of shipping into the Black Sea.

Trade now increasingly flows into Europe from the Mediterranean Sea, Miossec said, noting China’s growing interest in the region, showcased by Chinese COSCO Shipping’s acquisition of a stake in the Greek port of Piraeus in 2016 as part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Turkey is another important player in the Mediterranean, Miossec said, adding that Turkish ports have been upgrading in recent years. The Mersin harbor, the largest in Turkey, is in direct competition with Beirut, the geographer said.

In 2015, MSC’s container terminal operating business entered into a joint-venture to create a transshipment hub at Asya Port, outside Istanbul. When MSC relocated some of its transshipment from Beirut, it was to this Turkish facility.

“All experts say that the capacity of [port container] terminals of the Mediterranean Sea are not sufficient for expected growth in traffic in the coming years,” Miossec said.

USAID, in its assessment of the port, argued that Lebanon could quadruple its estimated 1.25 percent share of transshipment business in the Mediterranean and become a major transshipment hub.

But the broader changing tides of maritime business in the Mediterranean do not necessarily translate into opportunities for the Port of Beirut, with Miossec noting the immediate urban boundaries around the harbor that could stymie expansion of the relatively small container terminal.

A throwback to harbors from bygone years, the Port of Beirut is situated in the center of the Lebanese capital. Roland-Berger, the consulting firm that penned a proposal from German plans to develop the port, pointed out that the harbor “is situated in an area of prime real estate, on land valued at $5-10 billion.”

The Germans’ plan proposes moving port facilities eastward from their current location while emphasizing billions of dollars worth of real estate development around the current harbor. A more conservative reconstruction plan pitched by Lebanese businessmen Maroun Helou and Antoine Amatoury, which assumes port traffic to remain in the doldrums, calls for transferring some of the port’s real estate to the Lebanese state.

The sources interviewed for the article, professionals and businessmen often at odds in many of their views, all acknowledged the allure of the Port of Beirut’s real estate. They also all expressed consternation for the future of the facility amid the tangled jockeying of the country’s ruling politicians.

“They’re killing the port,” one executive, who didn’t want to be named, warned of feuding Lebanese politicians.