Installation view ‘The Return,’ 2023, eight walls, double-sided wallpaper, collages, sixteen modified automobile-headlight sculptures. Variable dimensions. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

BEIRUT — A good deal of “The Return,” Rayyane Tabet’s current solo exhibition at Sfeir-Semler gallery, is concerned with narrative. It’s the story of a marble sculpture of a bull’s head, dated around 360 BCE, unearthed during an archaeological dig in Saida in July 1967. With four other antiquities looted during Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war, the piece was repatriated and displayed at the country’s national museum in early February, 2018.

Tabet’s show recounts the sculpture’s journey in the decades between its rediscovery and its triumphal return. It’s a compelling tale that plumbs the demimonde of the global antiquities trade — the contemporary art market’s older brother — the semi-celebrity hubris of American collectors, honorable museum administrators and the US justice system.

The structure of the eight chapters of “The Return” is chronological, related by reproductions of primary sources — excavation inventories, police reports, invoices, shipping documents, loan agreements, customs declarations, emails, and claims presented to New York supreme court — as well as published stories, most prominently one from “Homes & Gardens.”

‘The Return: 1979 – 81,’ 2023. Wallpaper, modified automobile-headlight sculpture. Wall dimensions: 350×350 x 70 cm. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

‘The Return: 1979 – 81,’ 2023. Wallpaper, modified automobile-headlight sculpture. Wall dimensions: 350×350 x 70 cm. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

Art exhibitions conventionally have something to look at aside from (indeed, instead of) text. Here the eye candy takes the form of large reproductions of eight photos taken of the bull’s head sculpture. Four of them were shot in 1967 by the wife of Maurice Dunand (1898-1987) — a prominent French archaeologist who excavated Byblos from 1924 to 1975. Four were taken in by anonymous agents of US Homeland Security in 2017.

Ways of seeing

Exhibition summaries can be misleading. Having read this one, a reader may be forgiven for thinking “The Return” is about a fragment of antique sculpture.

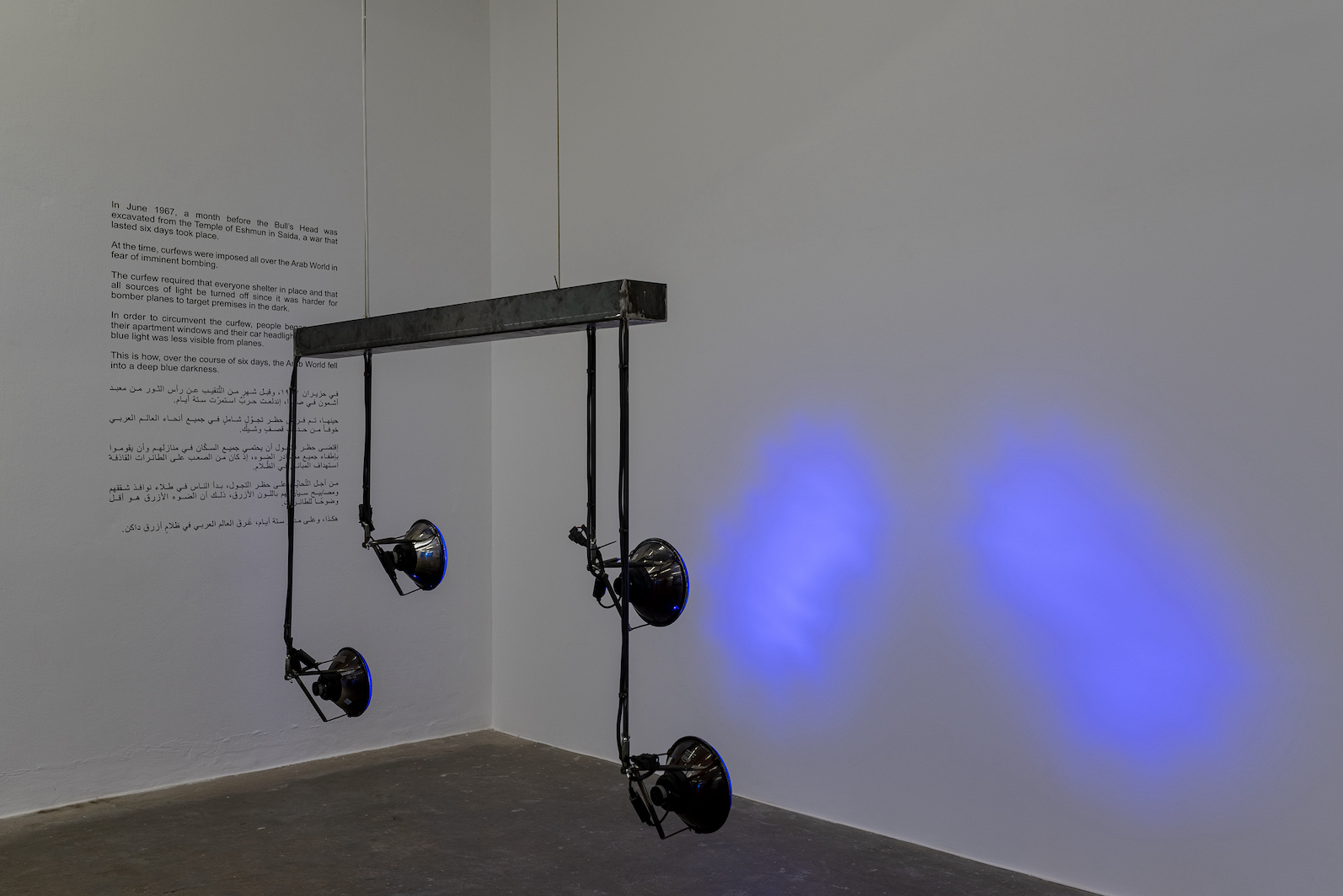

Detracting from that impression somewhat are the modified automobile headlights illuminating Tabet’s work. The lighting design — the lamps have been painted to give them a blacklight blue effect — has been attributed to family anecdote. During the 1967 War, it seems, Lebanese in the south of the country were warned that if they lit their houses or drove at nighttime they risked being bombed by the attacking air force. Loathe to live without light, many painted their windows and headlights blue, which was believed to be less blatant from above.

Bathed in this intense blue light — which endows the gallery assistants’ smiles with a fierce glow, while making the documents’ typeface difficult to discern without a judiciously applied yellow highlighting marker — observers may see that Tabet is interested in more complex matters of perception and adjudication.

“This show could have taken many different forms,” Tabet begins. “I spent a lot of time looking at the bull’s head at the national museum. You might borrow or replicate its form as a sculptural object ... There are many ways to represent that, maybe by going to the quarry in Greece, where the marble comes from, make an investigation, as I’ve done with other works.

“Then I realized that this object’s ‘object-ness’ was less interesting for me [than] its representation and reverberation. When it’s described in an inventory, or on an invoice, on a bill of lading, or those eight photos, when it appears in a catalog, or a loan agreement — those are also material and physical manifestations of this object.

“Not only is the story part of the life of this object, because [that story] makes it more valuable and hence more interesting,” he pauses. “Because it makes it more interesting, hence more valuable, I mean. There’s something in the language describing this thing that actually makes it an object ... It manifests it. For me this is in line with this investigation of perception and dematerialization.”

Eyeballing the documentation charting the sculpture’s sojourn in the US — when antiquities gnomes estimated the worth of the bull’s head to be between several thousand dollars and several million dollars — it’s not hard to agree with Tabet’s suggestion that an object’s meaning is invested by something other than its material form.

“This is something I’m exploring,” he adds. “I’m asking myself how the description of an object can be the object itself. Can the story actually be the object, as opposed to something separate, as it is usually seen to be?”

Installation view ‘The Return,’ 2023, eight walls, double-sided wallpaper, collages, sixteen modified automobile-headlight sculptures. Variable dimensions. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

Installation view ‘The Return,’ 2023, eight walls, double-sided wallpaper, collages, sixteen modified automobile-headlight sculptures. Variable dimensions. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

From narrative skepticism to dematerialization

“The Return” is Tabet’s third solo at Sfeir-Semler. He debuted in 2013 and has returned every five years to show the work of a discreetly evolving practice. His work has tended to materialize stories that resonate with the artist and his family as well as a wider public.

His gallery debut, “The Shortest Distance Between Two Points,” assembled fragments of TAPLine (The Trans-Arabian Pipeline, 1950-1976), which ran from Qaisumah, Saudi Arabia, to Zahrani, Lebanon. The TAPLine tale is an intriguing fragment of the region’s engagement with a nascent neoliberal economy, but Tabet sought to look beyond the broken, nostalgia- and melancholy-laden reminiscences to focus on the mute forms, objects and shapes evocative of that moment.

“I feel [that] objects … carry as much weight and energy as these stories,” Tabet said at the time, “except that people were telling me stories about things that happened in the past. This [abandoned infrastructure then still looming over parts of southern Lebanon] exists in our present.”

Members of Tabet’s family were among the cast of characters in the TAPLine story, but they were occulted from its forms.

With his 2018 solo “Fragments,” Tabet looked further back in the region’s history with a show comprised of historic and modern detritus of an early-20th-century archaeological dig at Tell Hallaf, northeastern Syria, whose remains date back to the Neolithic period.

The dig was led by Max von Oppenheim, a German diplomat and historian with connections to Deutsche Bank. The artist reconstituted the Tell Hallaf dig with work that included pencil rubbings and plaster impressions of artifacts on show in museums in Germany and the US. His efforts provoked questions about the preservation of archaeological artifacts, cultural appropriation and museological practices.

Tabet’s proximity to regional history was more visible here. French Mandate authorities, governing Syria and Lebanon in 1929, appointed Tabet’s great-grandfather, Faik Borcoche, to be Oppenheim’s secretary, charged with gathering information on his excavations.

‘Untitled,’ 2023. Metal structure, automobile-headlights, blue enamel paint, 106×86.5 x 32 cm. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

‘Untitled,’ 2023. Metal structure, automobile-headlights, blue enamel paint, 106×86.5 x 32 cm. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

Tabet tells L’Orient Today his current work is still too fresh to really discuss the interplay of narrative and form in “The Return.”

“This is really the first time that I show work that I’ve just finished,” he says. “Usually I have a little bit of distance, either from the research or from the physical objects themselves, so that by the time I put them out in the public, I already have a language to talk about and through them. For a variety of reasons, this is not the case here.

“One is practical. I could not test this [work] anywhere else before actually installing it. The other is deliberate. I’m questioning many things at the moment. For me, this shows a proposition. It’s an invitation to a conversation ... Instead of coming with the language to talk about the show. It’s more like, ‘let me make this gesture and see what it does.’”

Tabet speculates that his circumstances in the US may play a role in his approach to this work.

“In a way it reflects my complete separation from this city,” he says. “Though I have lived abroad for many years, my center of gravity was always here ... Now, for a variety of reasons, I’m spending a lot of time looking at the Pacific Ocean.

“I was interested to see how this story, which starts from something very local, takes place and is resolved in the US. Weirdly enough, it mirrors this trajectory that I’m finding myself in, kind of lost in this land that I’m trying to navigate.

Installation view ‘The Return,’ 2023, eight walls, double-sided wallpaper, collages, sixteen modified automobile-headlight sculptures. Variable dimensions. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

Installation view ‘The Return,’ 2023, eight walls, double-sided wallpaper, collages, sixteen modified automobile-headlight sculptures. Variable dimensions. (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg)

“My research for ‘The Shortest Distance Between Two Points,’ originated in my wanting to investigate a world that came before mine, since TAPLine collapsed the year I was born. ‘Fragments’ investigated a family story that took me back to the late-19th and early-20th centuries. The subject of ‘The Return’ is a 2000-year-old archaeological object, but it investigates the now. This dictated some of the show’s formal strategies, which ultimately became a show about light, about darkness, about perception, about what happens in the shadows.”

He pauses.

“I’m calling it my California phase,” he chuckles, “facing the very big horizon of the Pacific Ocean — cold, harsh, big, inhuman — as opposed to the Mediterranean, the body of water I was most familiar with. It’s warm. It’s closed. It’s welcoming. It hugs you, but there’s something about the harsh cold of this other body of water that I’m now attached to.

“Over the past 10 years, my conception and construction of what material and objects and form can and should do has tended toward de-materialization.” Tabet laughs. “That’s my answer.”

Rayane Tabet’s “The Return” is up at Sfeir-Semler gallery through August 16, 2023.