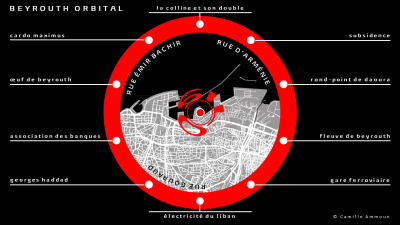

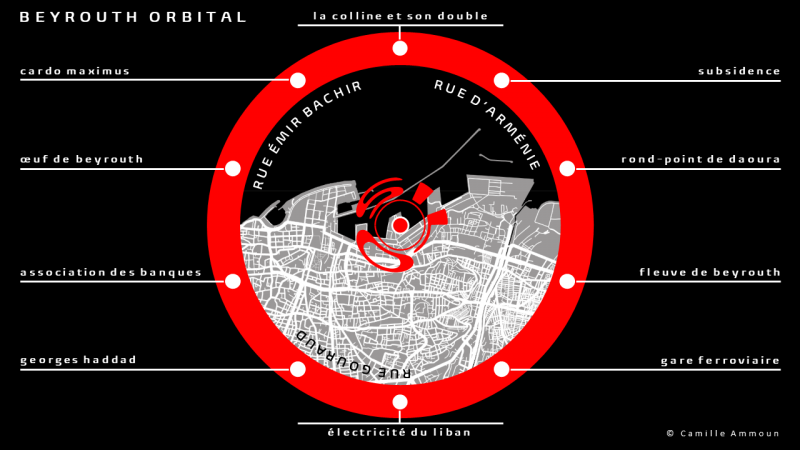

Graphic courtesy of Camille Ammoun

If you walk, if you write, if you go back to reality, to concrete, to the pavement of the street; if you deconstruct your walk into its simplest element — the step — if you walk alone or with people, you would perpetuate the simple act that led man out of Africa, and would repeat it in the cities man has built.

If you walk with a phone in your hand, if you stop in the middle of a sentence to browse a search engine or develop an idea; if you hear the rumor and listen to the fragments; if you look around, if you look beyond, if you look inside, if you read between the steps; if you scan the street with your eyes, if you probe the insignificant detail while embracing the great chaos of the world; if you digress, if you stumble, if you do not turn back but circumvent the obstacles or overcome the difficulties; if you know where you are going, but you do not know why you are going there, if you track down this “why” then, in doing so, you would be participating in the immense jigsaw of the world.

It was not a promenade that evokes a pleasant stroll. It was not a flânerie that suggests a romantic dimension. It was a simple walk, a banal juxtaposition of steps, a pedestrian prose. A prose that finds its final word here. Here, at the bottom of the Kantari hill where the Grand Serail became a Grand Bazaar. It was a drift in the heart of the urban incarnation of the concept of corruption. A drift that stumbles against this former Ottoman garrison, the headquarters of the Haut Commissariat during the mandate and, since Independence, the headquarters of the Lebanese Government.

In the early summer of 2005, the first post-Syrian “guardianship” legislative elections were held. They were clearly won by a coalition that would be called upon to govern in the presence of parliamentary opposition. After years of palsy, the democratic game began to open. On May 7, 2008, the parliamentary opposition sent its militiamen into the streets to thwart two decisions made by the majority government. Heavy clashes erupted throughout the country.

Two weeks later, on May 21, 2008, the Doha agreements put an end to the conflict and avoid a civil war. But they required the majority to form a government of "national unity.” The democratic game recovered its decade-long paralysis.. The ministerial shares in the government must now reflect the forces present in Parliament.

The legislative and the executive are now one. The institutions are de facto neutralized at the expense of negotiations between leaders of the traditional parties, the zaims. The Lebanese political class progressively melts into a magma of kleptocrats whose ultimate goal becomes the perpetuation of a corrupt system. It is a restoration of the pre-2005 regime, a "guardianship without a guardian."

Since then, ministries have been distributed, negotiated, and traded. The parties, looking for power to establish their legitimacy and funding to maintain their clientele, have their eyes on two types of ministries: the regalian ministries (defense, interior, foreign affairs, justice, finance) and the so-called "juicy" ministries (public works, energy, health, telecommunications).

By "juicy" it is meant that the ministries generate contracts to be distributed to their community, clients, clan, friends, family, and companies. On this hill, men pretend to govern other men, while they are themselves governed by their vanity, their egoism, and their libido dominandi.

While walking along this street of Beirut, it is all the shortcomings of men and all the failures of our contemporary world that I walked by. All of this between two hills— one formed by the multitude of wishes and objects once wanted, bought, then abandoned in bulk by men; and the other where their obscure desires for domination, control, and consumption are played out.

One and the other are now superimposed, and this walk transforms our long straight street into a circle. Here, in this column, the abandoned garbage and the trash that produces it overlap on the same locus. If the urban sentence of our Beirut street is long, narrow and almost straight, its transcription into a literary sentence is circular. It ends where it began, at the bottom of a hill, at the foot of a great bazaar of abandoned objects and obscure desires.

As Sinclair orbits London, here, it is by walking straight that we end up circling the city in a dizzying Beirut Orbital. Between the hill of waste of Bourj Hammoud and its Kantari twin, I saw motorists pile up at the entrance of cities accumulating distress and boredom. I saw filthy rivers dry up, forests torn away, and mountains eaten, I saw ghost trains connecting cities destroyed by wars and real estate developers. I saw diesel generators burning forests that have been sedimenting for millions of years to cool or warm living rooms and bedrooms, or charge phones where selfies on golden sunsets and other cute cat videos scroll by. I saw grain silos tell their own story from the moment of their erection to the moment of their evisceration.

I saw angry pedestrians cross vast intersections before vanishing like ectoplasms. I saw people become poor overnight and go far away to start over, and others stay with hunched backs. I saw places of worship pretending they are eternal and places of knowledge appear in the rubble only to disappear immediately. I saw subsiding cities sink into the ground and others, built on rocks, sink into the mud of corruption.

I saw all of this, and much more, as I was walking, as I was writing.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Camille Ammoun.