A view of the central skylight of Bernard Khoury’s “Plot # 4371”(2015). (Credit: Talal Khoury © Abbout Productions)

BEIRUT — Composer and filmmaker Nadim Mishlawi is inclined to distinguish between facts and truth.

“There can be a bit of a blur between documentary filmmakers and journalists,” he says, “because we’re both dealing with ‘reality.’ The journalist is more interested in facts. I’m interested in a more personal truth — maybe a fabrication of facts, or confusion of the facts — that sometimes are more accurate than what exactly happened.”

“I enjoy these discrepancies, between the way you remember things and the way they actually happened, like hearing five or six different versions of the same event, all completely different.”

Mishlawi’s reflections on the nuances of truth have arisen during his conversation with L’Orient Today about his new feature-length doc After the End of the World. The film explores the recent history of Beirut through its buildings. It draws upon the observations of four men invested in the city’s urban fabric. Among them is Mishlawi himself, whose family archive and emotional relationship to Beirut are at the center of the film.

Cast of characters

Bernard Khoury may be Lebanon’s most written-about contemporary architect, responsible for several of Beirut’s more innovative and challenging structures — including subterranean entertainment venues like B018 (1998) and Yabani (2002), and buildings that toy with humans’ elevator fetish, like Gemmayzeh’s Centrale restaurant (2001) and “Plot # 4371”(2015), the hand grenade-shaped residential structure in Jisr al-Wati. Multi-disciplinary artist Ziad Antar has long been preoccupied with photographing Beirut’s abandoned buildings, a project that found early expression in Beirut Bereft: The Architecture of the Forsaken and Map of the Derelict, his collaboration with writer-curator Rasha Salti. Architect and educator George Arbid is, among other things, the force behind the Arab Center for Architecture (Association for the preservation and dissemination of modern Arab built heritage).

Khoury was among the voices featured in Mishlawi’s first feature-length documentary, Sector Zero, 2011, a study of post-war trauma focussing on the neglected Beirut neighborhood of Karantina. The director acknowledges the two films’ relationship, while underlining their differences.

“After the End of the World grew out of Sector Zero,” he says. “The interviews with Bernard were like a catalyst that took me from one film to the next.”

Director Nadim Mishlawi says he wanted to shoot Beirut in an expansive way. (Credit: Mark Khalife © Abbout Productions)

Director Nadim Mishlawi says he wanted to shoot Beirut in an expansive way. (Credit: Mark Khalife © Abbout Productions)

“Sector Zero was all shot in close-ups,” he adds. “End of the World is kind of the opposite. It’s mostly filmed in wide-angle shots. You see a lot more expanse — landscapes, the sea, the mountains. The idea of doing something ‘broader’ was an aesthetic [as well as a narrative] choice, to breathe a little after the first film.”

Mishlawi didn’t set out to cast two architects and an artist in this film. Arbid and Antar came into the project at different points in its eight-year gestation.

“Someone suggested I talk to George because he has a unique vision of things and because of the Beirut Center for Architecture,” the filmmaker recalls. “I met him early on, before I thought of bringing in other characters.

“Ziad became part of the project when we decided to take the film in a different direction, maybe around 2017-18. I wanted the character to be a photographer or an artist but I’d never sat and spoken with Ziad, which was a bit weird. I think it wouldn’t have worked with anyone else. He’s very malleable and able to do a lot of different things, and he immediately understood what I was talking about. We ended up becoming friends in the process.”

Stories of a city

In After the End of the World, Khoury, Antar and Arbid depict a city that evolved more or less organically until the ruptures that of the late twentieth century — Civil War, post-war reconstruction (which did far more to destroy the urban fabric than the war itself), and the post-2006 war real estate boom that made it economically viable for developers to raze buildings that had survived the reconstruction period. Mishlawi says the film underwent substantial changes during production, mutating from Khoury’s guided tour of the city’s architecture to something more personal.

“It’s very difficult for me to think about Beirut without the personal anecdotes, personal histories, experiences,” Mishlawi muses. “It got to the point where the film was mostly about my relationship to the city, and interviews that expand upon that.

“Each interview was executed at a different point in the process,” he adds. “Some conversations have two years between the first and second interview.”

The film examines the dysfunctions that marked post-war Lebanon before the waves of crises that began washing over the country in 2019. It unfolds both chronologically and thematically. On one hand it grounds its interviews within this eight-year period, from Jan. 24, 2013 to Sept. 4, 2020. On the other the film is divided into four chapters and an epilogue — a coda remarking on the 2020 port blast, and how Beirutis seem “stuck in an endless present, between a past that won’t die and a future that’s been canceled.”

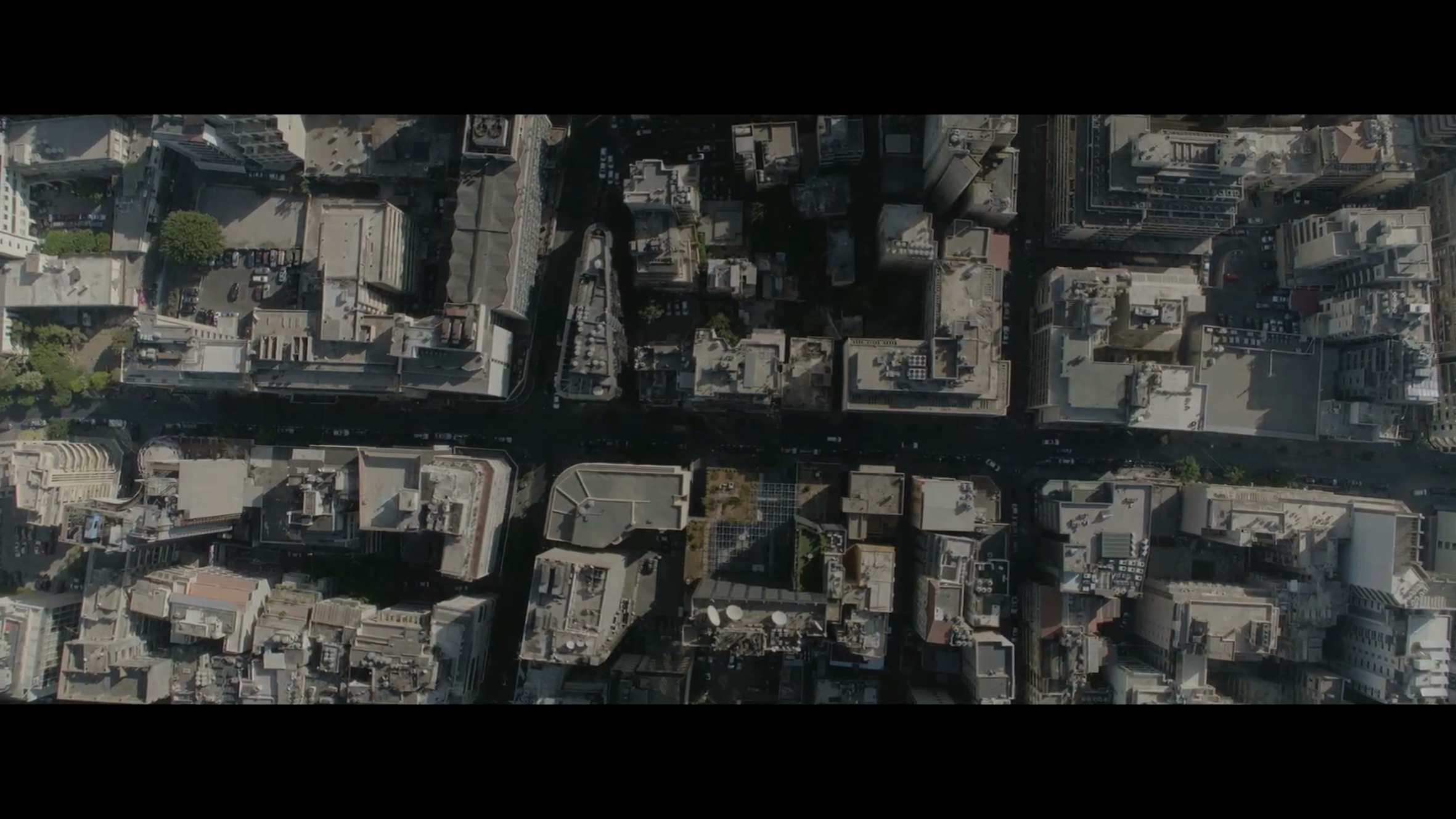

Beirut, which architect Bernard Khoury has compared to a crowded room where all the people stand with their backs to one another. (Photo by Mark Khalife © Abbout Productions)

Beirut, which architect Bernard Khoury has compared to a crowded room where all the people stand with their backs to one another. (Photo by Mark Khalife © Abbout Productions)

The first chapter, “Delirium,” introduces some of the symptoms of a city whose built environment since independence has been increasingly subject to market exigencies. Khoury compares Beirut to a room full of people with their backs turned to each other. “Like people, buildings don’t engage in dialogue unless there is some collective project,” the architect says. “Beirut has become like that,” full of solitary buildings, like islands.

Antar demonstrates the discrepancies between what’s depicted in real estate maps of the city and what actually sits in the ground. Arbid reflects upon the waves of tourists who came to Lebanon after the Civil War’s hostilities ceased in 1990.

“They were sad that we’d rebuilt,” he says. “They wanted to see the war. [It was a] tourism of war, poverty, destruction.

“People who endured the war don’t need a shelled building to prevent war happening again. It’s fetishism, this attachment to certain symbols and objects. A shelled building won’t prevent a new war. We need to work on improving our society.”

“Exhumed,” the third chapter, begins with a montage from an archaeological dig in downtown Beirut and veers from discussions of the post-Civil War reconstruction regime to Antar’s architectural photography to Khoury’s project to preserve the soul of a landmark structure (the former Laziza brewery in Mar Mikhael), whose demolition provoked controversy.

“Ghosts,” the final chapter, commences with footage of Beirut during the winter rains, when parts of the city invariably flood and sites visibly fray around the edges. Fountains of water are seen shooting up from storm sewers and a neglected cemetery's gravestones are shown toppled onto an adjacent street.

Mishlawi and director of photography Mark Khalife accompany Antar as a fisherman takes them for a sea view of Beirut. “To break with documentary tradition, I don’t take photos to show, but to feel,” Antar says as he shoots a few photos. “The act of photography is the act of killing a second. There is always sadness in it.”

Arbid too takes the crew beyond Beirut, leading them to his favorite space, a spot outside his mountain village, and a complex of boulders and cedars that form a natural shelter. “I wanted to show you this spot because it has architecture,” Arbid says. “No one built it, obviously, but there’s something about these rocks, and this special cedar … It must be 2,000 years old.”

“Burial,” the second chapter, is concerned with Arbid, Mishlawi and Khoury’s personal reflections on the city. In this chapter, the production footage of Khalife is complemented by substantial archival footage, captured when the filmmaker himself was a child. Much of this was shot by a crew of foreign television journalists who came to the Mishlawi family house to interview the director’s mother Phillipa and father Tewfik Mishlawi, a highly regarded Palestinian-born Lebanese journalist, before they were forced to leave Lebanon from 1985-92.

“I’d been wanting to use that footage in a project for a while and didn’t really know how,” Mishlawi recalls. “It was filmed in ’83 or ’84, I think. The journalists were friends of my dad’s and they gave him some of the other stuff they’d filmed around the city for the same report. We ended up using some of that as well.

“We were trying to emphasize this idea of home, the comfort and safety of domestic space and how at some point things fall apart during war. A lot of the choices were made by Ghina Hachicho [one of the film’s three editors, who made the final cut]. She suggested going deeper into the archive. At first I was a bit apprehensive, but she persuaded me. It works better with this material.”

Beirut as cinema

Long before Mishlawi made Sector Zero, he was involved in film production as a composer of film scores. It is in this capacity he and sound designer Rana Eid co-founded DB Studios, the city’s premier sound-centered post-production company. Devising the sound of Beirut, he says, was every bit as complex as it was to capture its image — particularly when it came to scoring the archival sequences involving his family.

“The archives are an important part of the film for me,” he says. “We didn't want the score to be too melodramatic, but at the same time it is an emotional, very personal, look back through time. I wanted to capture the idea of time passing, of things eroding. To do that I added a texture reminiscent of that hiss of magnetic tape, the crunch you have with a VHS tape. A lot of the sounds were actually textures that I’d recorded from VHS tapes and old cassette tapes from the war. I also re-recorded a lot of music to tape and then brought it back into the film, so it sounded much older.

“The sound design was going in the same direction. They would record a lot of the sounds onto tape and then bring them back into the film. We’re trying to create a blur between what’s sound and what’s music. Again, it was an aesthetic choice, because the film is about trying to remember things, which can be blurry, obscured, vague.”

An interior shot of the Georges Jallad Building, former home of the Laziza brewing company. (Credit: Mark Khalife © Abbout Productions)

An interior shot of the Georges Jallad Building, former home of the Laziza brewing company. (Credit: Mark Khalife © Abbout Productions)

Mishlawi’s crew also includes a foley artist — specializing in creating artificial facsimiles of natural sound — a trade conventionally associated with fiction film that nonfiction filmmakers have been more likely to add to their toolkit in the past couple of decades.

“I love documentaries that are stylized and subjective,” Mishlawi confesses. “So I suggested recreating the sound details of some scenes, like in one scene where Bernard moves in his chair and you hear it squeak. The archaeological excavation sequence [at the start of “Exhumed,”], that’s all foley. None of it is production sound.

“Again, it’s about bringing subjectivity to the story, allowing the sound crew to interpret things the way they wanted.”

The film ends with a semi-comic conversation about remembering the city. It’s conducted on a vacant parcel of land between the northern edge of Solidere and the peninsula of reclaimed land called “New Sector” on some maps. Here, Antar explains, there used to be an exhibition space, where he once had a solo show.

“They exhibited the photos here,” Antar gestures frenetically with his arms to suggest the scale of the show. “Asir, Kamal Salibi, Saudi, all here.”

“I’ve never seen an exhibition here,” mumbles a confused-looking Mishlawi.

“Two years ago there was a huge center here,” Antar rejoins. “The wall was 16 meters long.”

“What happened then?” the director asks. “Where did the building go?”

“I don’t know,” Antar shrugs. “The exhibition ended. Two months later the building vanished.”

“I don’t remember a museum or anything like that here,” Mishlawi repeats.

“It doesn’t matter,” Antar replies, impatient now. “There was a museum once. Now it’s gone … Enough nostalgia. I’m telling you I had an exhibition here.”

“I know this plot of land was always empty.”

“No,” the artist insists, pointing into the near distance. “Before the museum opened, there were mechanics over there … I’ll bring photos of the show, since you don’t believe me.

“You keep saying this place is empty, but there’s history here. … You walked by it with your father and ate ice cream. Here there was the hospital. I had shots here,” Antar pantomimes a jab in his shoulder. “You can’t rely on your childhood memories of the city, some landmark that showed you where the sea was. Don’t rely on those. Look at it as a story.”

In fact this site was formerly occupied by the Beirut Exhibition Center, which in March 2016 hosted Antar’s show “After Images,” a photo series putatively centered on Saudi Arabia’s Asir Mountains — a claim that was difficult to confirm visually, since the photos were shot with a lensless camera. Not long after, the structure housing BEC was dismantled and removed.

“That scene is completely scripted,” Mishlawi tells L’Orient Today, chuckling. “It’s improvised but scripted. There are a couple of scenes like this in the film.”