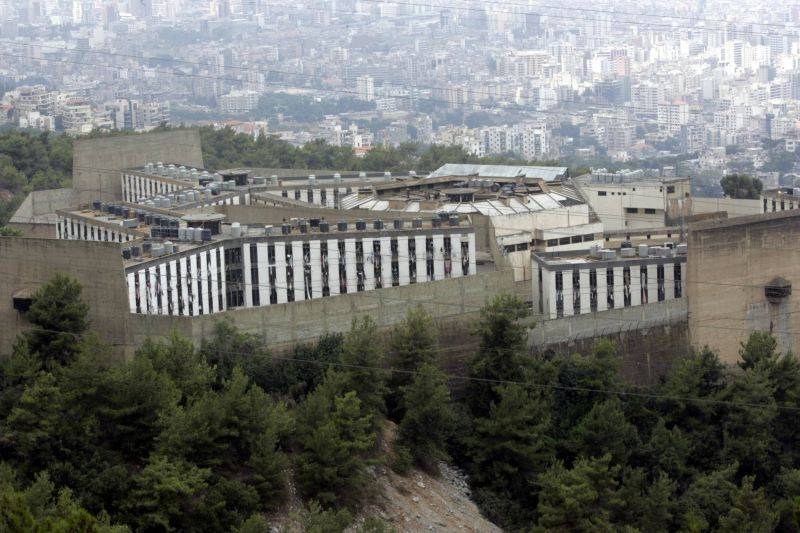

At Roumieh prison overcrowding is an endemic issue. (Credit: A.H. Assaf)

The detention conditions in Lebanon’s prisons are marked by a conspicuous lack of food — and what is available is of poor quality — medications and health care.

In many cases, detainees remain behind bars for months on end, even years, without trial.

These already deplorable conditions have become intolerable since the outbreak of the economic and financial crisis in Lebanon in late 2019.

The problems of the prison system are no longer limited to overcrowding and promiscuity amongst the inmates; they are now also reflective of the state’s inability to feed, care for and try its prisoners.

Two prisoners have recently died because of the lack of adequate care, and civil society groups are concerned about the increasing number of deaths.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the situation, as has the number of drug addicts in detention due to the lack of specialized facilities and an open strike by judges since mid-August to protest the record depreciation of their salaries, which remain paid in Lebanese lira, a currency that has lost more than 90 percent of its value in the past three years.

Recently, six commercial suppliers of food to Lebanon’s prisons issued an ultimatum to the Interior Ministry, threatening to deprive prisoners in several incarceration facilities of food if the state did not pay them dues that had been outstanding for seven months.

While most of the Lebanese population, deeply affected by the crisis and the depreciation of the national currency, is struggling to make ends meet and is largely turning a blind eye to the fate of some 9,000 detainees (in prisons and detention centers) throughout the country, the political class is active in an announced objective to limit prison overcrowding.

This comes in a context of a rise in prison breaks, the latest of which took place on Sept. 23, when 19 prisoners escaped from a prison in Jounieh.

Amnesty vs. reduction of prison year

Two draft bills were presented to Parliament in August. MP Ashraf Rifi (Independent/ Tripoli), who formally served as justice minister and head of the Internal Security Forces, made a proposal titled “exceptional amnesty” for certain crimes.

“It calls for exceptional measures to relieve prison overcrowding, because the situation of prisoners has never been worse,” Rifi told L’Orient-Le Jour.

Under the proposal, “the death penalty would be reduced to 25 years of imprisonment and life imprisonment to 20 years,” he said. “In addition, the prison year would be reduced from nine to six months, even for those sentenced to death and life.”

As for the defendants, “they will also benefit from the law, if it turns out that they have served enough [of their sentence],” Rifi added. “The judicial system is in complete deadlock and the detainees are unfortunately paying the price, especially those awaiting trial,” he continued.

According to Rifi, some “two-thirds of the country’s prisoners are still waiting to be tried.”

Omar Nachabe, an expert on prisons in Lebanon, told L’Orient-Le Jour, “This is a controversial number. Many prisoners have been convicted several times.”

Meanwhile, the bill presented by the government, through caretaker Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi, advocates the reduction of the prison year from nine to six months, applicable only once, i.e. the term reduction will not be applicable to anyone convicted after the bill’s adoption.

This project does not affect those sentenced to death or life imprisonment, many of whom are Sunni Islamists who have perpetrated terrorist acts or violent attacks against the Lebanese Army, in Nahr al-Bared (2007), Dinnieh (2000), Abra (2013) or Arsal (2014), not to mention the major drug traffickers and many criminals.

“Those sentenced to death will have their sentences commuted to 25 years imprisonment and those sentenced to life imprisonment [will have their sentences commuted] to 20 years. Their prison year will count 12 months,” according to the text of the law L’Orient-Le Jour reviewed.

Possible consensus, after amendments

“Five laws aimed at solving the problem of prison overcrowding are waiting to be discussed in Parliament,” MP Michel Moussa (Amal Movement/Zahrani), chairman of the parliamentary human rights committee, told L’Orient- Le Jour.

Since it is “out of the question that the authorities grant an amnesty,” even on an exceptional or partial basis, which would privilege Sunni Islamists convicted of terrorism (there are 500 of them, according to Sunni religious authorities, less than half of them Lebanese), “the bill presented by the interior minister, with amendments, seems the most likely to be the subject of consensus within the political class,” according to Moussa, who is close to Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri.

The situation in prisons is so alarming that the issue could even be raised at the Parliament’s session to discuss the budget, according to the two aforementioned MPs.

“Never before have we seen such overcrowding in the country’s prisons,” Moussa said. “For example, the prison of Roumieh, with a capacity of 1,300 inmates, now houses nearly 5,000.”

He added, “However, the draft bill will follow the regular procedure. It will be presented to Parliament, transferred to the parliamentary committees and then to the general assembly for a vote.”

What justice is there for the victims?

However, as criminality flourishes in Lebanon against the backdrop of state institution collapse, we must ask if sentence reduction by half — not to mention amnesty — and thus the early release of major criminals, regardless of their community affiliation, really is the best solution?

What about the duty of a nation to establish justice and respect for the rights of victims and their families?

In other countries, sentence reduction measures are usually limited, decided on a case-by-case basis, conditioned by the exemplary behavior of a prisoner or by their obtaining a job, among other conditions.

Yet, from their jails, many of Lebanon’s criminals continue their illicit activities. They do not benefit from any rehabilitation, any training, any job.

“They lead an idle life of deprivation, under the boot of the Shawish (a detainee who has certain power and influence with a cell, and sometimes can abuse their position), and many of them sink into drug addiction, or even sexual addiction,” Nachabe said.

“They continue their trafficking within the prison without being worried,” Father Najib Baaklini, president of the Association of Justice and Mercy (AJEM), which is active in the Roumieh prison, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

“When they are released, many of them have no prospects. They face unemployment and usually they relapse into criminal behavior, which does not please their relatives,” he added.

An inconclusive first attempt

This is not the first time the Lebanese authorities have attempted to reduce prison overcrowding.

About 10 years ago, the prison year was reduced from 12 to nine months.

But “no study has ever been conducted to measure the consequences of this first reduction of sentences,” Nachabe explained.

It appears, however, that the results have not lived up to expectations.

“This measure did not solve anything,” according to an informed source who spoke to L’Orient-Le Jour on condition of anonymity. “The proof is that a few years later, the country’s jails were overflowing again, including detention centers.”

“Reducing the prison year to six months will undoubtedly empty the prisons of 1,000 to 2,000 people,” said Nachabe, who is in favor of “anything that can alleviate the prison congestion in these difficult times.”

He, however, stressed that this could lead to “an increase in crime and [a] high risk of recidivism.”

Baaklini is similarly skeptical. “We can only be in favor of lessening prison overcrowding. But I don’t see how reducing the prison year solves the problem of overcrowding in places of detention,” he said.

What is more problematic for the humanitarian associations present in the prisons is that “when politicians speak out in favor of an amnesty or a reduction of the prison year, they are pressured by the families,” the informed source said.

Anger of reformers

The issue of prisons has always been the subject of political and communal tug-of-war, exploited by leaders for electoral or clientelist purposes.

It has never been approached in the interest of Lebanese society, nor in a perspective of reform, but in the interest of religious communities.

The recent initiatives are no exception to the rule, provoking the anger of political figures that have been long committed to reforming the system.

“These bills look like a declaration of impotence. Reducing a year in prison by half is a form of amending the penal code,” according to legal expert and former Interior Minister Ziyad Baroud, who is also a human rights activist.

“A general amnesty would be a shocking measure. It is a headlong rush, a populist and electoral approach,” Ibrahim Najjar, a former justice minister, told L’Orient-Le Jour.

He, however, added that given the current situation, a solution to prison overcrowding, such as shortening the prison year, is understandable.

When they were in office, the two officials cooperated on reforming the prison and judicial system, rearranging sentences and working to bring responsibility for the management of the prison system under the remit of the Justice Ministry rather than the Interior Ministry.

But their efforts never came to fruition.

“The equipment and infrastructure that we had installed in Roumieh to improve the daily life of prisoners were even ransacked and burned during riots,” Baroud told L’Orient-Le Jour.

What alternatives are there in this context?

“It is necessary to think about the judicial and prison policy, but also to effectively empower the Justice Ministry to deal with the issue of prisons,” Baroud said, stressing that the management of prisons is not part of the prerogatives of law enforcement forces.

Given the increase of population, “it is also necessary to build prisons in a decentralized manner, so that families can visit their detained relatives without it costing them a fortune in travel,” he added.

For his part, Najjar has been tirelessly calling for “a well-thought-out prison strategy” and “functioning courts so that judgments can be rendered.”

“All this is not the fault of the prisoners. When the courts are not functioning, thousands of detainees are kept in prison without knowing whether they are guilty or not,” he added, denouncing “the absence of the state.”

Thirteen of the 19 fugitives who escaped Friday night from a prison in Jounieh, the main city of Kesrouan, were arrested over the weekend.

Twelve of them were apprehended on Saturday morning, according to an announcement by the Internal Security Forces. The 13th was arrested Sunday in Akkar by the Lebanese Army at a checkpoint in Shadra, the army said in a tweet.

Police said the search is ongoing to apprehend those detainees still on the run. The circumstances of the escape were not disclosed by the authorities.

In early September, 10 prisoners escaped from the al-Hisba police station in Saida, South Lebanon.

In August, more than 30 prisoners broke out via a window at a detention center near the Justice Palace in Beirut. Only a few of them were eventually found by the police.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.