Ania Soliman. (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

BEIRUT — The automobile-sized elevator clanks into place. Its doors slide open and out of them pour a smattering of artists and art lovers, to mingle with those already strolling Sfeir-Semler Gallery’s exhibition halls. It’s the opening night of “Terraform,” the Beirut debut of Paris-based artist Ania Soliman.

The Baghdad-reared, Egyptian-Polish-American painter and videographer bases her practice in line drawing. This is Soliman’s first show in the Middle East, but she’s been exhibiting — and winning prizes — since 2010. Gallery owner Andrée Sfeir-Semler is known for her lineup of respected and salable contemporary artists, many of whom come from the MENA region. She shows their work at her Hamburg and Beirut galleries as well as contemporary art fairs worldwide.

The artist recalls that Sfeir-Semler had proposed an exhibition at her Hamburg gallery, but Soliman insisted on staging the exhibition in Beirut.

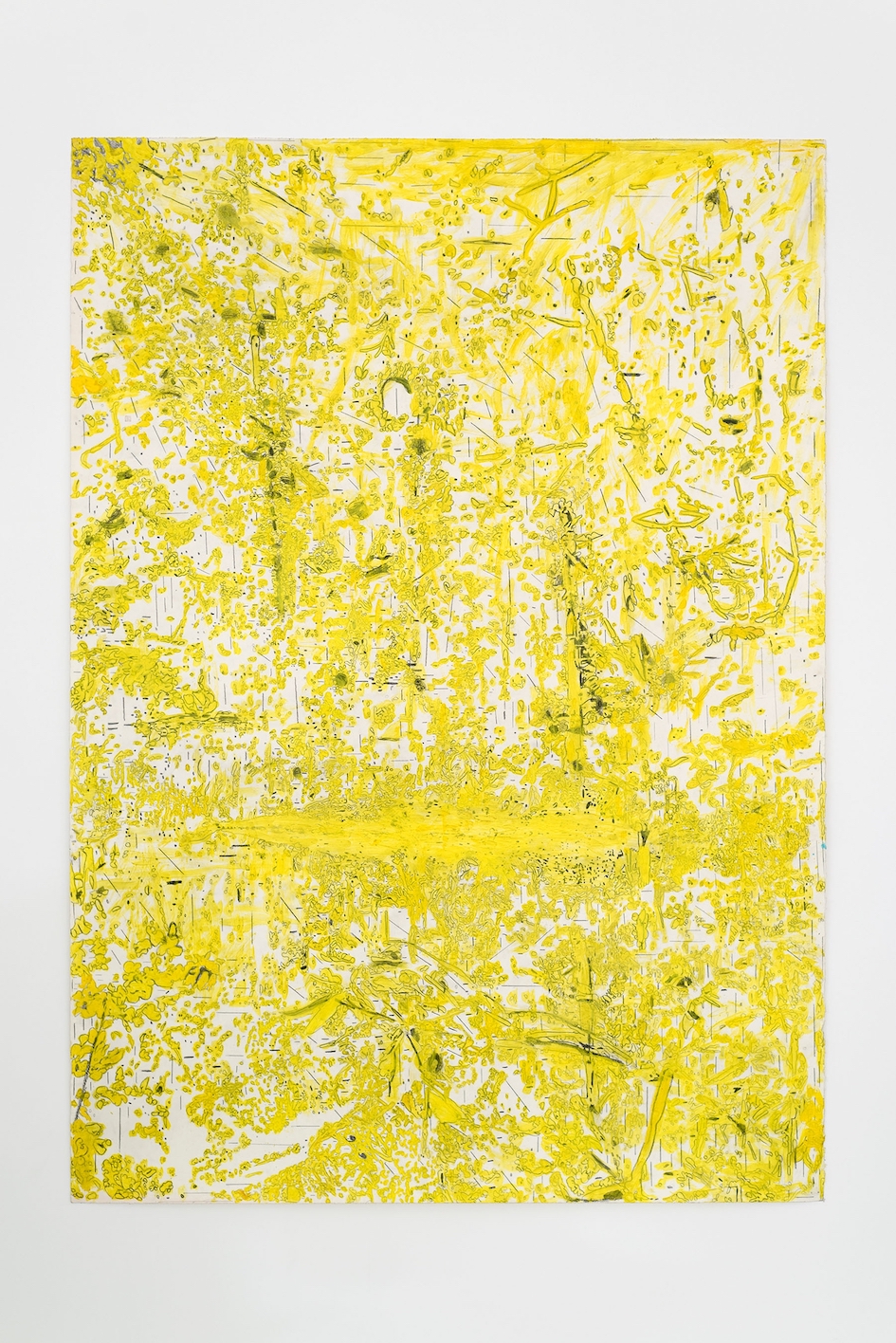

“Machine memory” (rainforest 2), 2019. Encaustic, pigment and pencil on paper, 200 x 140 cm (unframed). (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

“Machine memory” (rainforest 2), 2019. Encaustic, pigment and pencil on paper, 200 x 140 cm (unframed). (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

“It’s like connecting to my origins, and I wanted to make a gesture of solidarity, to connect to what’s happening here and to do some work that’s physically rooted in this place,” she tells L’Orient Today. “I have no specific connection with Lebanon except the Arabic language, but I feel at home here — the city, the culture. The worst has happened so many times over and over, yet people are so kind, so generous and funny and loving.”

Soliman is interested in real and imaginary relationships between nature and technology — negotiated on a late-capitalist/post-colonial landscape. As the title of the Sfeir-Semler show suggests, her work continues to explore these themes.

Wax-on-paper works

Upon entering the gallery, viewers are confronted by the exhibition’s titular piece, “Terraform 1 (everyone-zoospore, recovery-whew),” 2022. The titles of many of Soliman’s works are derived from either a random word generator algorithm or algorithmic mistranslations from Arabic.

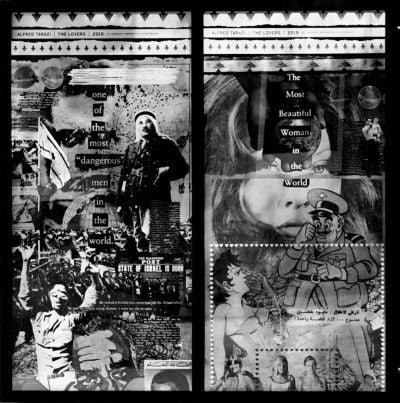

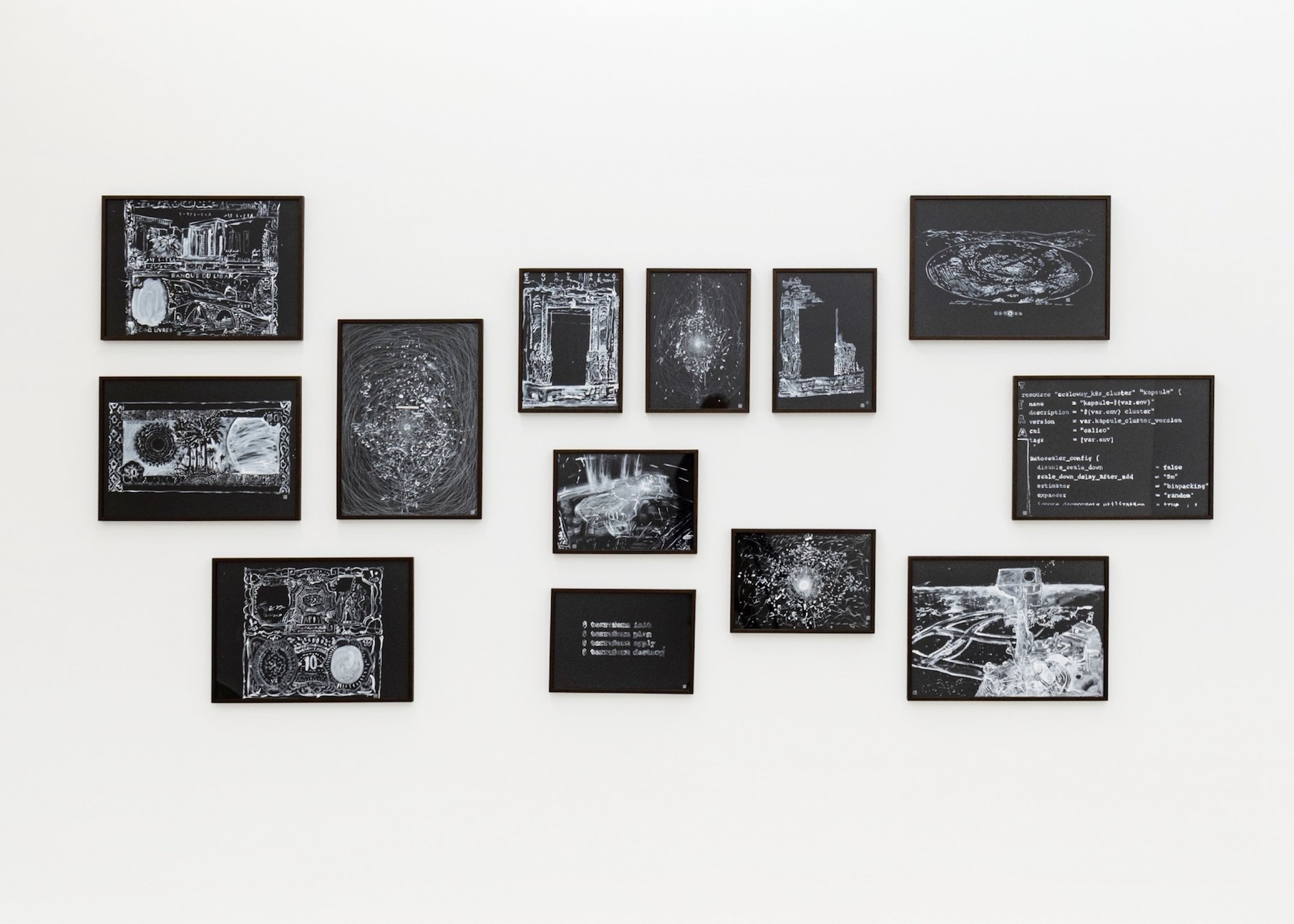

Soliman’s “Insomnia drawings,” 2022. Ink on paper. Series of 13 drawings, 61.5 x 44.5 x 3 cm or 44.5 x 32 x 3 cm. (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

Soliman’s “Insomnia drawings,” 2022. Ink on paper. Series of 13 drawings, 61.5 x 44.5 x 3 cm or 44.5 x 32 x 3 cm. (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

“I kept seeing this word ‘terraform,’” the artist recalls. “I became obsessed with it, in a love-hate kind of way. Obviously it’s a science fiction term for re-engineering planets to resemble the Earth to sustain life, but the use has increased since 2014. I thought it was because of the Mars rover missions — for a long time there have been dreams of terraforming Mars — but it turns out it’s also the name of a programming language. Companies use it to terraform the cloud.”

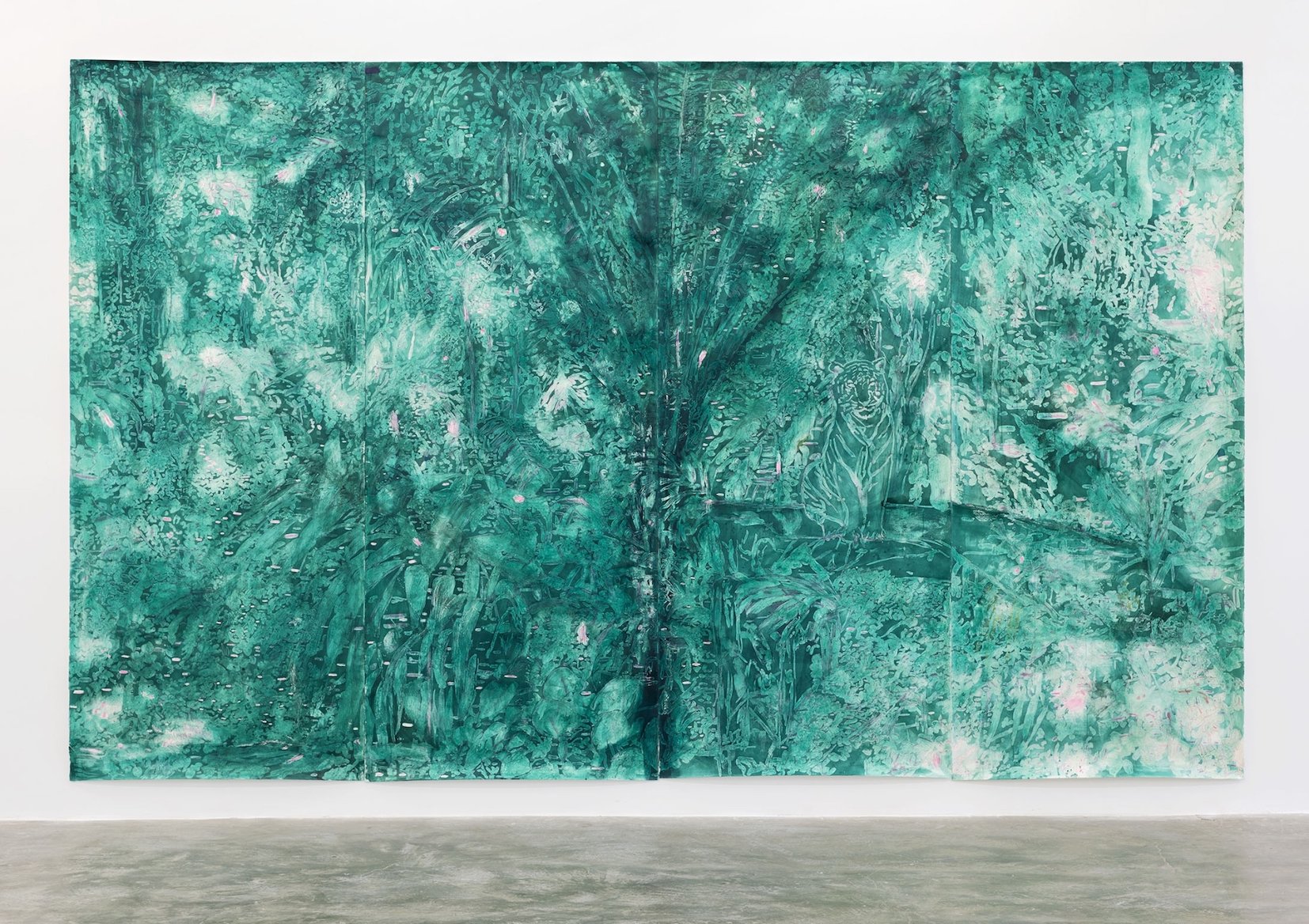

A monochrome (Soliman calls the color “acid green”), “Terraform 1” depicts a rainforest scene. Traces of relatively-exposed surface suggest light penetrating the canopy to dapple the dense vegetation. To the right, a tiger sits, attentive as a tabby.

Landscape painting is a deceptive form. Styles vary but, from the look of it, it’s just nice scenery. On the other hand, the history of landscape painting is entangled with that of Western imperialism — in the European and settler colonial sense of entitlement over, and ownership of, the land it depicts.

Soliman’s choice of materials may reflect her sense of art history. “Terraform 1” is an encaustic (wax) and pigment-on-paper work. Its four panels measure 280 x 115 cm, and the work’s size conspires with the paper’s frailty to make it seem all the more delicate. The artist’s relationship with the landscapes she represents is also informative.

“relative-folio-foothill (arabian)” (Witnesser 1), 2022. Spray paint on canvas, 180 x 200 x 2 cm. (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

“relative-folio-foothill (arabian)” (Witnesser 1), 2022. Spray paint on canvas, 180 x 200 x 2 cm. (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

“Basically, I’ve been drawing rainforest images since childhood,” she says, “which is weird because I grew up in Baghdad, but there’s always been this real connection to the structure and the image of the rainforest.

“Usually I find images in archives. I’m really interested in early photography,” she explains, “but during the pandemic, I started thinking that these days we’re connecting to nature more through the screen.”

“This image,” she nods at “Terraform 1,” “is a screensaver.”

Is there a sense of irony in connecting with nature “through the screen”?

“Ironic,” Soliman agrees, “and not. I mean, that’s what we are nowadays, cyborg entities.”

Most of the exhibition consists of works on paper and canvas that the artist made between 2019 and 2022, several of which emerged during her five-week Beirut residency in August. “Terraform 1,” an older piece, is among several encaustic-on-paper studies of rainforest landscapes.

“I’m quite obsessive,” she says, “so when I find an image and its structure, I draw it and redraw it, then redraw it some more.”

An exhibition view of Ania Soliman’s “Blue Works,” 2022, in “Terraform.” (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

An exhibition view of Ania Soliman’s “Blue Works,” 2022, in “Terraform.” (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

Archival origins

The elevator door again grinds open. The space is beginning to buzz as early arrivals, having made their rounds, cluster near one corner of the foyer, where a pressed barman stands alert behind his stacks of bottles.

Soliman’s encaustic-on-paper works were inspired by an image she found a decade ago — an archival photo from the early 20th century taken by a Swiss anthropologist in the Malay Archipelago. That foundational photo gave rise to many pieces, among them the portrait-shaped “Machine memory (rainforest 2),” 2019.

While she was working on this photo, Soliman says she was thinking about French intellectual Georges Bataille (1897-1962), specifically his pioneering work of political economy The Accursed Share. “He writes about how nature is at the source of all value,” she says, “and about the accumulation of excess value — basically re-thinking human economics, not separating us from nature or ‘natural economics.’”

As viewers penetrate “Terraform,” it becomes obvious that Soliman’s offhand depiction of humans as “cyborg entities” is no casual joke. The thinking behind her works, and the objects they represent, reflect a refreshing, and at times disturbing, summation of the human condition under late capitalism.

“I’m really interested in the relationship between the organic and the machine-ic, between nature and technology,” Soliman says, “and how we’re used to separating ourselves from both. [I’d like] to erase those distinctions, in a way, and that motivates the formal processes, but also the language, the ideas behind the work.”

Dominating the foyer of the gallery is Soliman’s “Terraform 1” (everyone-zoospore, recovery-whew), 2022. Colored pencil, encaustic, acrylic ink on paper, 4 panels, 280 x 115. (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

Dominating the foyer of the gallery is Soliman’s “Terraform 1” (everyone-zoospore, recovery-whew), 2022. Colored pencil, encaustic, acrylic ink on paper, 4 panels, 280 x 115. (Walid Rashid/Sfeir-Semler Gallery)

The formal process in Soliman’s encaustic pieces relates to how to determine the figure-ground relationship — that is, which parts of a dimly lit photo represent trees, shrubs, etc, and which are the ground — a problem she overcame by drawing a grid of pencil lines as the formal basis of the work.

She points to slight traces of the grid-work of “Terraform 1.” “I think of myself as a machine. Like a machine, I choose plus, minus, plus, minus, plus, minus. So I make the decision and the line designates the structure of the work. The image is like choreography. My body repeats, repeats, repeats, repeats, until it almost becomes part of the physicality. Then I finish. Once an image is too familiar, I don’t do it anymore.”

Soliman’s practice of obsessive, machine-like repetition of forms, most obvious in her encaustic-on-paper works, suggested other post-industrial metaphors.

“I was thinking how we live in rococo [elaborately, or excessively decorative] times — this culture that’s so over-extended, that’s about to crash but we’re still pursuing obsessive repetition. We can’t stop. There was a pause during the pandemic and everybody’s been waiting for it to rev up again, though we know it’s toxic.”

This line of analogy brought the artist back once again to the term “terraform.”

“It occurred to me that all forms that are made by nature, even the ones we make, are terraforms. I turned it around, and started thinking about the miraculousness of form. Nature started this repetitive form-making thing, and we’re just part of that. It will go on after we’re gone, or whatever we transform into. In a way, we cannot separate ourselves or anything we make from whatever nature makes: We’re just her agents. We can’t help our madness of overproduction. If it doesn’t work, nature will eliminate it. We’re an experiment.”

Nature and technology on canvas

Most of the new work on show in “Terraform” also explores contemporary relationships between technology and nature but employs slightly different media and forms to do so.

“I’ve been trying to work on canvas, without any luck,” Soliman explains. “I love paper, but I decided to bring some canvas with me. Somehow being in Beirut allowed me to move into this new work.”

The show includes several spray paint-on-canvas works — smaller brightly hued monochromes, conventionally stretched and framed, and larger blue paint-on-white canvas works, hung as ceiling-to-floor drapes. For each canvas the artist has used machine parts and plants (natural and plastic) as stencils for the spray paint.

While making these curtain-like pieces on the roof of the Karantina building housing the Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Soliman says she was “thinking about the arabesque, and how its use of organic elements and geometric elements problematizes figure-ground relationships.”

These works create the impression of an unhinged immersive environment — plants with machine parts grafted onto them, or leafy, worm-like cyborgs, at once metallic and organic. They press against the canvas like children upon a car window, demanding attention.

“Terraform” will be up at Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Karantina’s Tannous Building, through Jan. 7, 2023.