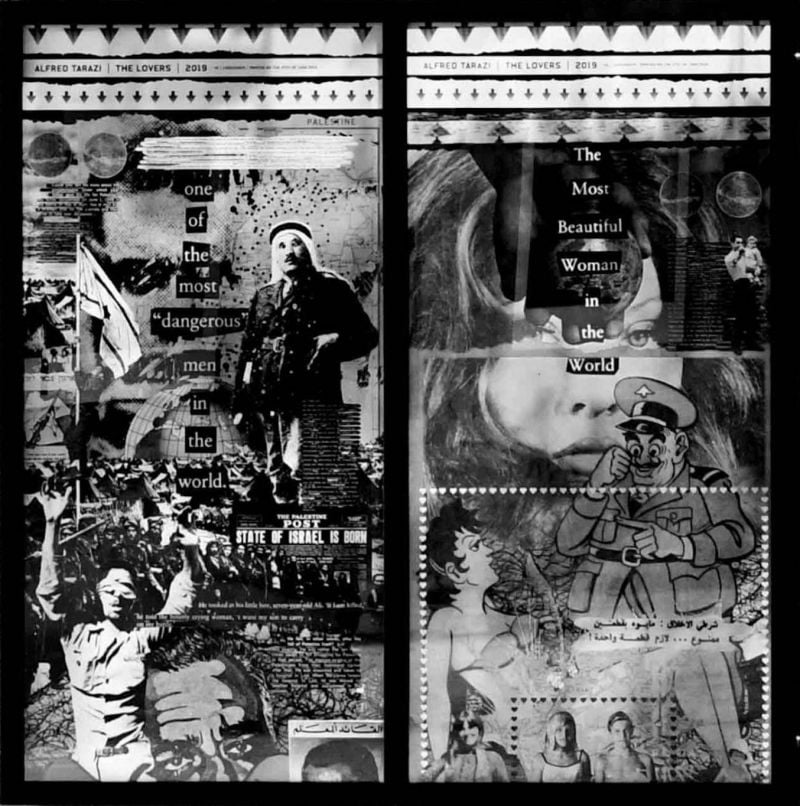

One of the works in Tarazi’s "The Lovers," a study of media depictions of Miss Lebanon Georgina Rizk and PLO operative Ali Hassan Salameh, first presented with Galerie Krinzinger at Art Dubai, 2017, later installed during Beirut Design Week, 2019. (Courtesy of the artist)

In an otherwise empty café in Badaro, Alfred Tarazi is reflecting, a little reluctantly it seems, on his trajectory as an artist.

His current show, “Memory of a Paper City,” is on display at The Hangar exhibition space in Haret Hreik run by the UMAM Documentation and Research, a local nonprofit dedicated to the study of Lebanon’s violent history.

“Memory of a Paper City” offers a visual précis of the stories that simmered in Lebanese pop culture in the period before and during the Civil War. The violence of the Civil War and Civil War-era “celebrities” are present but there are other motifs. Most evident, and titilating to audiences of the popular press, is Lebanon’s sexual revolution: depictions of women’s bodies and conservative responses to the apparent breakdown of social norms. Lebanese warlords are in evidence, as are cultural figures like composer Ziad Rahbani and caricaturist Pierre Sadek, but so is Che Guevara and Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo. There are plenty of depictions of semi-nude women in cheesecake poses, but space is also alloted to Palestinian militant Leila Khaled. This multi-layered installation relates a cultural history of the period, but it’s really a history of the iconography diffused through print media.

A detail from the three-dimensional collage at the center of Tarazi’s "Memory of a Paper City’"ongoing at UMAM’s The Hangar, Harat Hreik. (Credit: Dia Mrad)

A detail from the three-dimensional collage at the center of Tarazi’s "Memory of a Paper City’"ongoing at UMAM’s The Hangar, Harat Hreik. (Credit: Dia Mrad)

Discussing this show requires not only recalling Tarazi’s relationship with The Hangar’s proprietors, but also his struggles to find his voice as an artist born in the midst of Lebanon’s Civil War.

In 2007, Tarazi met Lokman Slim and Monika Borgman, founders of UMAM, during a symposium they hosted about creating a Civil War memorial.

Later, they collaborated in the 2010 multimedia exhibition “Sea of Oblivion,” installed inside Beirut’s ruined City Centre Cinema (“The Egg”). The exhibition was partially financed by Lebanon’s Ministry of Culture — a major coup, since the ministry’s default setting is that it has no budget to fund Lebanese art.

“UNESCO had named Beirut the World Book Capital for 2009,” Tarazi recalls. “They actually had a surplus of a couple of million dollars ... The lady who was in charge was very strict about funding projects. She was adamant. ‘I’m not corrupt,’ and so on.”

Tarazi says he mounted the show “to rally people around a memorial for the victims of the Lebanese Civil War,” an issue that has been more frequently explored in conferences and similar civil society events.

The installation’s visuals, devised with artist/architect Maxime Hourani, included Tarazi’s large collages of photos from the conflict. Sound artist Tarek Atoui and improv artists Fadi Tabbal and Stephane Rives contributed to the sound piece that echoed through the venue. UMAM exhibited photos from its “Missing” project — portraits of people who disappeared during the war years.

His enduring relationship with UMAM is currently on show in “Memory of a Paper City,” an open-ended exhibition dedicated to the memory of Slim, who was assassinated in South Lebanon in Feb. 2021, just as Tarazi’s project was being prepared.

A detail from the three-dimensional collage at the center of Tarazi’s "Memory of a Paper City’"ongoing at UMAM’s The Hangar, Harat Hreik. (Credit: Dia Mrad)

A detail from the three-dimensional collage at the center of Tarazi’s "Memory of a Paper City’"ongoing at UMAM’s The Hangar, Harat Hreik. (Credit: Dia Mrad)

On a sultry Beirut morning, Tarzai sat with L’Orient Today to discuss his latest collaboration, and the contours of a practice preoccupied with inconvenient — and neglected — swathes of history.

Violence, the art world and UMAM

Born in 1980, Tarazi and his creative contemporaries are burdened with belonging to the generation following the “1990s generation” of artists — many of whom have enjoyed robust careers in international contemporary art circles — which he says made him feel restricted in how to pursue a practice rooted in historic documentation.

It’s difficult to generalize about the work of these artists — who work in mediums as diverse as photography, performance, film and plastic art — but there has been a common desire to avoid work that could be seen as partisan (many Lebanese artists had supported one side of the conflict or another and had made art in support of their cause) and to abjure images of graphic violence.

“What binds me to Lokman and UMAM … is their investment in Lebanon’s violent history, in purging that violence,” Tarazi says. “It’s a violence that’s constantly feeding on itself, perpetuating itself, yet it’s something that I don’t see in the work of the postwar generation of artists.”

From "Sea of Oblivion," installed inside Beirut’s ruined City Centre Cinema in 2010. (Courtesy of the artist)

From "Sea of Oblivion," installed inside Beirut’s ruined City Centre Cinema in 2010. (Courtesy of the artist)

After some years of frustration, Tarazi started working with Vienna’s Galerie Krinzinger. In her mid-20s, gallery founder Ursula Krinzinger started representing the Viennese Actionists, who were pioneers of performance art.

“Ursula built her early career working with this post-World War II generation that was dealing with the our-parents-did-not-speak trauma. ‘They pretend to be nice people but look what they did.’” Tarazi pauses. “I guess it resonated, where I was coming from.”

In his current “Memory of a Paper City” exhibition, Tarazi’s source material is a number of political and non-political magazines produced by the ten press groups active before and during the Civil War — including familiar titles like Dar al-Nahar, Dar al-Safir, Dar al-Hayat and Societe General de Presse et d’Edition.

Photos and caricatures are enlarged as cutouts and arrayed on a terrace at the center of the exhibition space. On either side of this three-dimensional collage, a selection of plastic-sheathed magazines hang in two rows of stacks. Flanking the stacks, the walls exhibit what might be thought of as Lebanon’s ‘Top 20" stories, from 1949 to 1990. Entitled “Bikini,” the oldest is a caricature of a corpulent policeman leering at a swimsuit-clad woman; the most recent, “Dani Chamoun,” is accompanied by a photo of the assassinated politician’s corpse.

“Memory of a Paper City” is the fruit of research, but it’s also a collection. Tarazi says his first tranche of documents came to him from a friend’s father, who had to give away his collection after he ran out of storage space. It ended up in the artist’s studio.

Eventually, Tarazi focused his energies on mapping two Beirut lives: that of Ali Hassan Salameh, the PLO operative assassinated by the Mossad (Israeli intelligence service) in 1979 for his involvement in the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, and his wife Georgina Rizk, who shot to fame after being named Miss Universe in 1971.

An installation still from Tarazi’s 2015 French Institute show “Monument to Dust,” drawing on pieces from Maison Tarazi’s back catalogue. (Courtesy of the artist)

An installation still from Tarazi’s 2015 French Institute show “Monument to Dust,” drawing on pieces from Maison Tarazi’s back catalogue. (Courtesy of the artist)

Tarazi’s digging came to form a project called “The Lovers,” exhibited during Beirut Design Week in 2019.

The collection grew exponentially during this research, he says, and it inspired the artist’s current, more ambitious, “Memory of a Paper City.”

Tarazi says the next stage is to take “Memory of a Paper City” to video. “The next step is to animate these images and narrate. They will tell the story of sexual liberation and the Palestinian revolution and the impact that both of them had on the Lebanese Civil War.

“This work is important from an art historical point of view,” he says. “You’re looking at a world that was fashioned by artists, assessing the impact they had on history ... Back then you see artists are fashioning, they are constructing these images that are moving things.”

A family patrimony

Tarazi is now working toward another exhibition, scheduled to launch in October, that at once echoes his practice and is quite distinct, especially in material terms.

“It’s my family’s history,” he says, “which came to me in the form of a warehouse filled with wood and copper.”

Maison Tarazi, founded in 1862 and active until 1975, commissioned and distributed the sort of wood and metal work that is synonymous with high Ottoman culture in the Mashreq (modern day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq). The artist says his inheritance includes a stockpile of finished pieces and the unfinished components of pieces.

“Some of the objects date from the mid-1900s, even older,” he says. “My father was completely unable or unwilling to do anything with these things. Since 1975, the moment they closed their shop, these objects have been rotting, gently.”

The work of Maison Tarazi hasn’t been utterly forgotten. Camille Tarazi, the artist’s cousin, has documented the family archives in his 2015 tome Vitrine de l’Orient — Maison Tarazi, fondée à Beyrouth en 1862.

An installation still from Tarazi’s “Memory of a Paper City” ongoing at UMAM’s The Hangar, Harat Hreik. (Credit: Dia Mrad)

An installation still from Tarazi’s “Memory of a Paper City” ongoing at UMAM’s The Hangar, Harat Hreik. (Credit: Dia Mrad)

Beirut’s French Institute also hosted an exhibition of a sample of these historic objects in the 2015 show “Monument to Dust.” Otherwise, the artist says, his efforts to activate this material have been frustrated. He found a path forward when a proposal was accepted for an exhibition at Lebanon’s National Museum, but that show was put on hold because it was decided that some of the materials should not enter the museum.

At this point the exhibition will be in two parts. Part of it will be staged in front of the National Museum, he says, while the rest will be in an adjacent venue.

“It’s strange,” Tarazi muses. “In the National Museum, you have glorious antiquities, though of course you have a few artifacts that are more recent. Then, at Sursock, say, you have modern art. Between antiquities and modern art you have 2000 years of, like, ‘What did we do?’

“This material is politically delicate in the sense of where it should be placed. Do you place it in a museum of Islamic art or in a museum of decorative art? Do you show it in a museum of handicrafts? There are multiple places where you can show this material, but each [requires] a political decision”.

These objects are vestiges of a pre-nationalist cultural production, which makes it difficult to assert ownership in an age of (often contending) nation states.

“Is it Lebanese? Is it Syrian? Is it Jordanian? Palestinian?’ Whose is it? Somehow nobody, literally nobody, wants to claim it. And the know-how [to create and conserve such work] is dying.”

This refusal to own Ottoman-era art objects, Tarazi says, means that it’s all but impossible to see such work today. The sole location in Beirut is Robert Mouawad Private Museum, in Zuqaq al-Blat, originally built by the Tarazi family’s one important collector, Henri Pharaon (Lebanon’s Foreign Minister in 1945, 1946-7), who built a palace and filled it with Damascene woodwork.

“I’m super excited to present this material,” Tarazi says. “For me it’s a magical repository of geometry.”