BEIRUT — “I suppose painting was always there.” Walid Sadek gazes into the distance, as if in reluctant agreement. “Maybe I’ve been turning around something in my head, trying to find ways to paint.”

The artist is sitting with L’Orient Today in the middle of the generous subterranean hall of the Saleh Barakat Gallery. He blinks at a wall currently hung with his work.

“Then again, I don‘t want to make it seem like this is just a continuation. I like the idea of—” his hands gesture a sharp break. “It’s okay to cut and not be able to fully explain the cut.”

Sadek goes on: “Lately I’ve been reading [Vietnamese-American novelist] Viet Thanh Nguyen,” he says, a smile spreading. “Very interesting guy. He says, ‘Contradiction is the body odor of humanity.’”

He laughs quietly and raises an arm modestly.

“You can smear on as much deodorant as you want.”

Saleh Barakat is hosting Sadek’s first Beirut solo show in 12 years, “Paintings 2020-2022.” Anyone visiting this show who is at all familiar with Sadek’s practice might be curious about what sort of irony its title implies.

An exhibition shot of "Paintings 2020-2022." (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

An exhibition shot of "Paintings 2020-2022." (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

Currently the chair of AUB’s art department, Sadek’s art and critical writing are part of a surge of creative production from a group of Lebanese contemporary artists whom international art curators dubbed “the ’90s generation.” Though all their work has been influenced by having come of age during the Civil War, their concerns and practices have been diverse — ranging from film to photography, performance, plastic art and writing. Like most all his colleagues, Sadek formed a creative relationship with Christine Tohme, founder of the Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts, Ashkal Alwan.

“My so-called generation did various things at the time,” he reflects. “I think what’s important is that the work that I was doing was intimately connected with the ethical question of ‘How is one to be an artist after the Civil War?’”

Sadek’s concern with the ethics of postwar aesthetics made his work uniquely rigorous. For much of his career, he restricted himself to a black-and-white palette, frequently deployed as lines of allusive, lyrical Arabic prose.

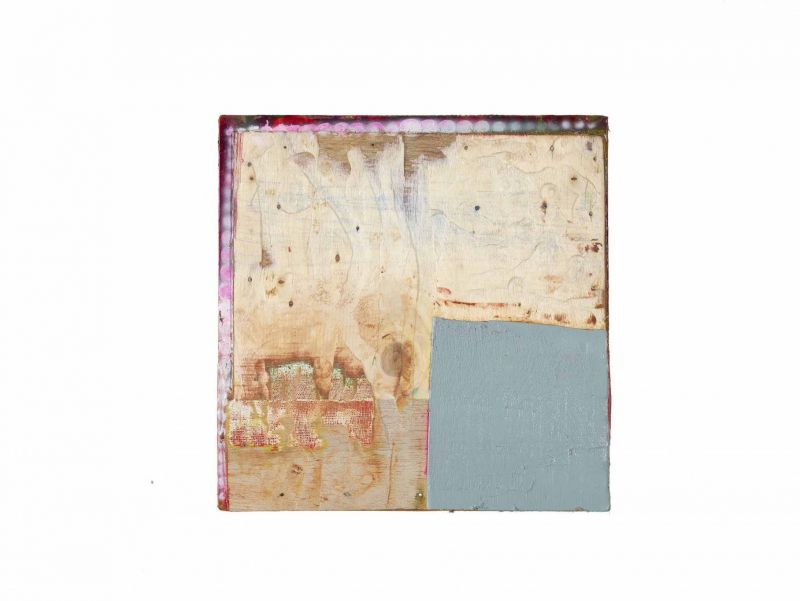

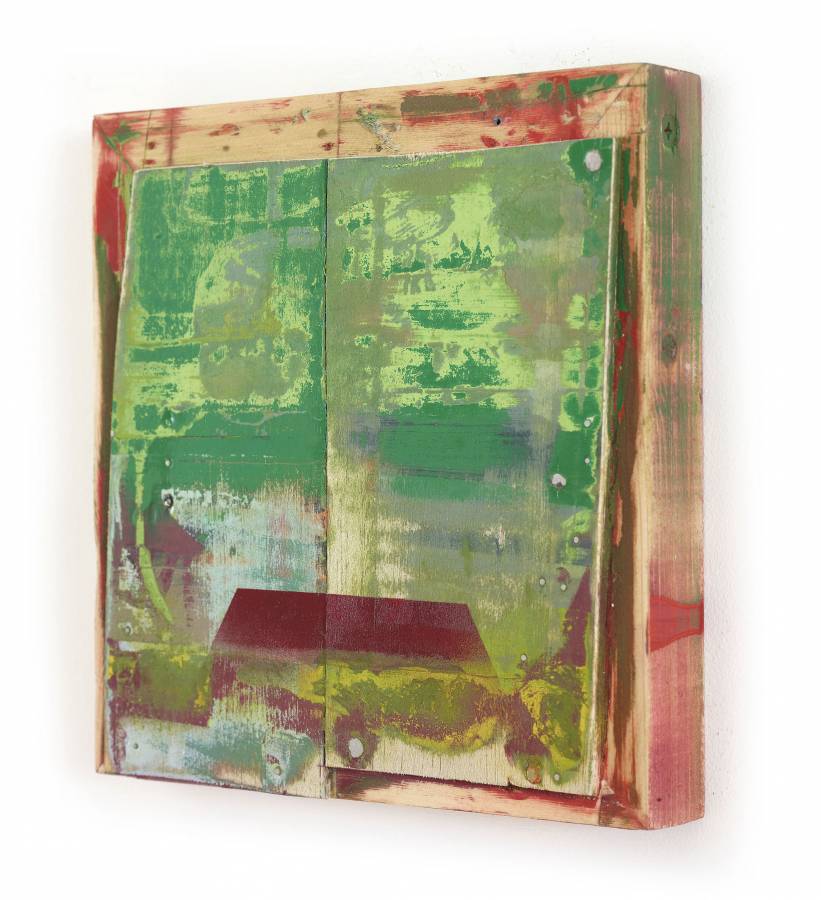

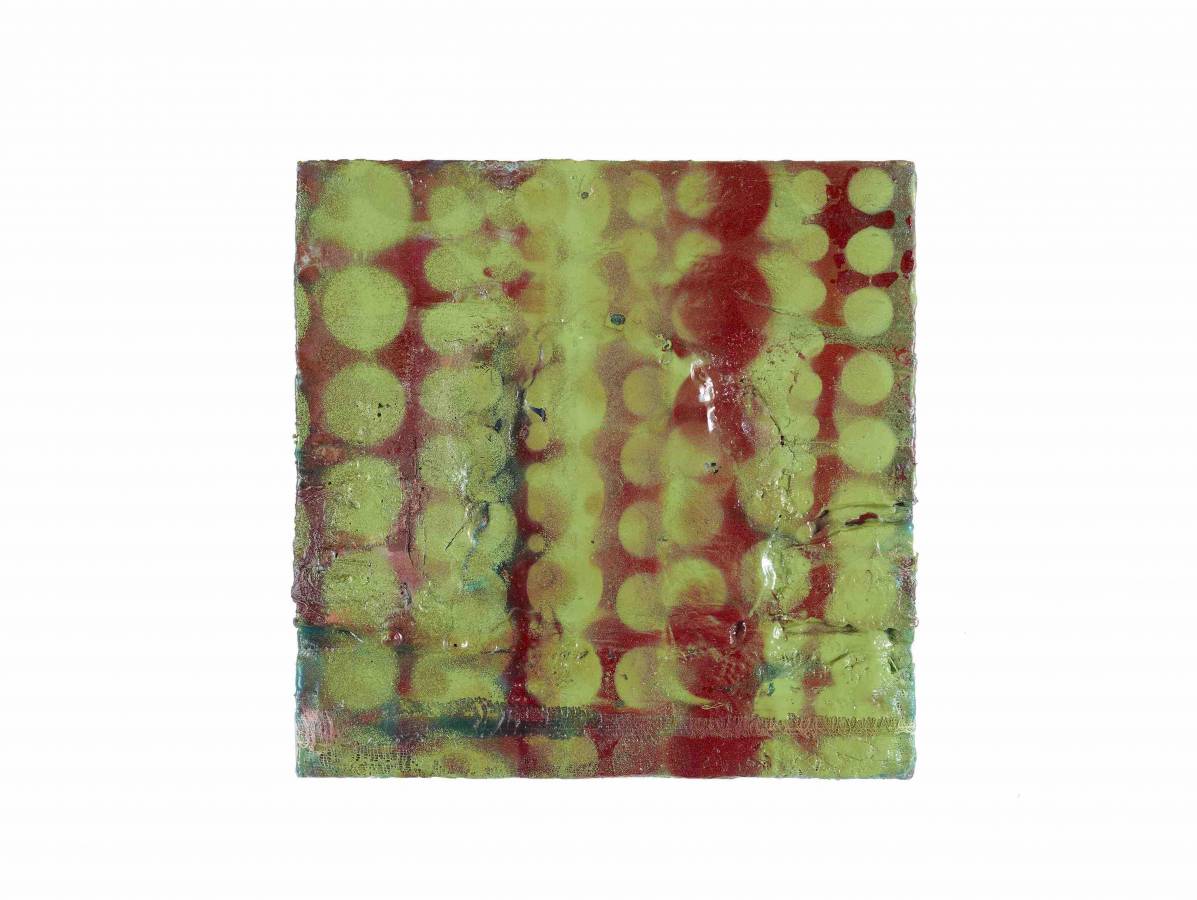

“Paintings 2020-2022” is comprised of 26 miniature paintings. Most are square works of 25x20x3cm, deploying an array of media (encaustic, oil and acrylic paint, enamel and acrylic spray paint, as well as plaster, papier-mâché, gauze, screws and nails on various types of wood). Various paints also adorn a smaller number of circular aluminum sheets (25x20x3cm), formed with sculptural and pictorial elements.

Walid Sadek. “Untitled,” enamel paint, enamel spray paint, balsa wood, birch wood, nails, approximately 20x20x3cm. (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

Walid Sadek. “Untitled,” enamel paint, enamel spray paint, balsa wood, birch wood, nails, approximately 20x20x3cm. (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

“The choice of materials started from a lack of funds,” he says, “but as I was working, I realized that every time I tried to stretch a canvas I would feel totally blocked. The material of canvas seemed overly occupied by art history. So no canvas.”

Untitled and unencumbered by exhibition tags, these 26 pieces are freestanding works, most hung about a meter apart. Layers of media have been applied, then abraded, but they’ve been subjected to varying degrees of violence, so each suggests different degrees of complexity and density.

Most startling of all, these works are unfailingly colorful.

Ashkal Alwan and dancing with the corpse

Sadek showed his first work in Lebanon in 1995, during Ashkal Alwan’s Sanayeh Garden Art Meeting. The first open-air contemporary art exhibition held in the Ottoman-era garden, the event showed the work of 39 then-aspiring artists.

“Those were exhilarating times,” he recalls, “this idea of the beginning of the post-war period.”

He wanted to use Beirut’s first post-war art gathering “to do a bit of excavation. Not to resurrect the corpse, but to see if we can dance with it, to linger with it.”

Walid Sadek. “Untitled,” acrylic paint, acrylic spray paint, aluminum sheet, approximately 25x20x3cm (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

Walid Sadek. “Untitled,” acrylic paint, acrylic spray paint, aluminum sheet, approximately 25x20x3cm (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

His Sanayeh Garden work “was a series of small paper cut-outs, hung on the garden’s peripheral fence. It proposed a kind of dance macabre — dance with the dead — with Ibrahim Tarraf Tarraf.”

A law student, Tarraf was accused of murdering his landlady Mathilde Bahout and her son Marcel and dismembering both their bodies. He was tried and convicted of two counts of first-degree murder on June 30, 1980. President Amin Gemayel ordered he be publicly hanged in Sanayeh Garden, and the execution, carried out on the morning of April 7, 1983, provoked considerable controversy. Since Tarraf’s “confession” had been obtained under torture, many believed the execution reflected Tarraf’s guilt less than state hubris.

The execution inspired much work among local artists, including books by Hasan Daoud and Yusef Salameh and a stage play by Roger Assaf.

Accompanying Sadek’s cut-out was a text that veered between descriptions of sexual pleasure and evocations of pain, with pictures taken from an encyclopedia of tools used to puncture surfaces.

“We were so innocent. We were hanging out in the garden and three men came by, asking about the work. I thought they were art lovers.” He chuckles. “Later on I was told that they were mukhabarat [military intelligence].”

Walid Sadek. “Untitled,” encaustic paint, enamel spray paint, papier-mâché, gauze, fir wood, approximately 20x20x3cm. (Courtesy Walid Sadek)

Walid Sadek. “Untitled,” encaustic paint, enamel spray paint, papier-mâché, gauze, fir wood, approximately 20x20x3cm. (Courtesy Walid Sadek)

Sadek’s previous Beirut solo, “Place at Last,” shown at Beirut Art Center in 2010, was a visually understated, altogether less-colorful affair than his Saleh Barakat exhibition.

Inscribed on paper and the gallery walls, many of the lyrical Arabic texts in “Place at Last” referred to paintings from art history but these works weren’t reproduced in the show. Instead, website coordinates to images of the works were available on a piece of paper, along with translations of Sadek’s poetic prose.

“Love is blind,” 2006, one of the pieces in “Place at Last,” suggested his relationship to painting at that time. The work is a conversation with 10 paintings Lebanese artist Moustafa Farroukh produced between 1933 and 1952. Farroukh’s romantic depictions of Lebanese landscapes were themselves absent — vacant frames served as placeholders. Their exhibition labels were there in full, as were Sadek’s lyrical rejoinders.

To Farroukh’s “View of Beirut” (c1952), for instance, Sadek replies, “This city is not here. Pilgrims will not find in it a shrine to circumambulate and to no avail will believers proclaim their divorce with its place. Names are fated to be abandoned by us as we are fated to be abandoned by places.”

By the time he reached his final semester of art school in the US, he explained in a 2010 interview with this writer, he’d “realized that ... painting was too much about pleasure and not enough about thinking.” The problem persisted back in Beirut. “Whenever I put something that was in my mind into a drawing or a painting, it’d be painfully too little. The idea seemed much better.”

Sadek’s sea change: Form

Sadek regards the work in “Paintings 2020-2022” as marking his third run as an artist “and its guiding element,” he says, “is form, more than narrative.”

He knew something had changed in late 2016, when he received some installation photos of “Walid Sadek: Thoughts on Speaking Dead,” an exhibition of his work in Mumbai.

“I said, ‘I need to stop this work that I’ve been doing for 10 years,’” he recalls. He felt that Lebanon’s post-war condition, the subject of his work, had ended, he says, “though not because we’d accomplished anything.”

An exhibition shot of “Paintings 2020-2022.” (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

An exhibition shot of “Paintings 2020-2022.” (Courtesy Saleh Barakat Gallery)

“So I devoted myself to building the AUB art department. Then, gradually, the desire to make art resurfaced.

“I just finished writing an essay about this idea of the time after post-war. I thought, ‘Okay, let’s see if I can make an art that no longer carries the burden [of the Civil War].’”

The AUB art department launched weekly drawing sessions that attracted models and artists from various universities.

“Ironically, I fell in love with the world during those years,” he smiles. “I used to bicycle almost daily to the Dalieh [a once unspoiled patch of coast in northwest Beirut imperiled by luxury development]. There, on the rocks, I drew the city, for about four or five years I think. I learned to look at colors and shapes, to appreciate the world again.

“Around 2020 I felt like I was ready to go to the studio and begin to invent, to build. Painting seemed the most challenging and difficult thing to do. Building a painting has been challenging,” he pauses, “but it attracted me because it was something I could do without using language.”

Sadek has been having conversations with modernism again, but not all modernism — re-reading the work of the French group, “Supports/Surfaces,” active in the late ’60s early ’70s, “who understood abstraction not as an idealist proposition, but as a materialist one.”

Compared to the art discourses he’s participated in for the past 20 years, “which always came with text, curatorial statements, big narratives about what the art was supposed to be,” Sadek says, “painting seems relatively defenseless. Maybe that seems appropriate to these times?”

His gaze falls back on the walls.

“After I installed the work – for the first time I felt like I was offering works that wanted first to share a certain visual pleasure. From that visual pleasure perhaps conversation can ensue — something more intellectual, something about art history and so forth. But first, the content is in the looking, as [American painter] Ellsworth Kelly used to say.”

He glances into his discarded tea cup.

“It‘s funny, some of my ‘post-war artist’ friends came — Akram Zaatari, Marwan Rechmaoui, a few others. Some were excited by the work. Some wrote to say they felt really energized by it. Others left without saying goodbye.

“I realized that [my change in direction] might be losing some people, but gaining others. The older generation was really receptive. I never really thought about them that much before — older artists and non-artists. They used terms that I often thought of as being, um ...

“‘Beautiful.’ That’s not so bad.” He chuckles. “Are all these signs of growing older?”