Artist Akram Hajj during a performance of ‘Waters’ Witness – Beirut,’ at Ashkal Alwan’s Mar Mikhael space, 14 July. (Credit: Lara Saab / Courtesy Ashkal Alwan)

BEIRUT — Facing onto the Gemmayzeh steps (aka Daraj al-Fan, the “Art Steps”) is a hotel with a fondness for apricots. In its café, filled with hipsters one Monday evening, open laptops accompany the conversations, infusing the air with a sense of furious creativity.

Couples gesture at shared screens, like pairs of TV doctors scrutinizing chest X-rays. Others evoke lounge bar piano players, tapping at keys while drinking and chatting. All hands seem oblivious to the calamity that tore through this neighborhood from the nearby port two years ago, and the pandemic that has been waxing and waning since early 2020.

Christine Tohmé is a little late. The founder and director of Ashkal Alwan (the Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts) has been outside Beirut today, offering condolences, so her conversation with L’Orient Today has a somber start. Her spirits soon rise, though, buoyed perhaps by the chorus of greetings from various patrons — folks from the city’s creative sector — and by the possibilities of the association’s new space.

The latest iteration of Ashkal Alwan is located just down the street in Mar Mikhael. Tucked behind a Grab’n’Go on Armenia Street, the neighborhood’s main drag, the shopfront windows reveal a high-ceilinged white cube-style space with a set of stairs leading to an office and a kitchen area in a smaller adjoining room.

“There’s a different energy here,” Tohmé says, smiling. “It has a different relationship to the audience. If you want it to be a completely enclosed space — like if you do an exhibition — you just close all the shutters. If you want it completely open, and extend the project to the alleyway or the street, you could do that. The space is never the same.”

Tarek Atoui during a performance of ‘Waters’ Witness – Beirut,’ at Ashkal Alwan’s Mar Mikhael space, 14 July. (Credit: Lara Saab / Courtesy Ashkal Alwan)

Tarek Atoui during a performance of ‘Waters’ Witness – Beirut,’ at Ashkal Alwan’s Mar Mikhael space, 14 July. (Credit: Lara Saab / Courtesy Ashkal Alwan)

Farewell Jisr al-Wati

Ashkal Alwan (literally “Shapes and Colors”) is a non-profit dedicated to producing, disseminating and discussing contemporary art. Founded in 1993, it is the most persistent of a handful of organizations birthed in Beirut in the wake of Lebanon’s civil war. It has worked with dozens of Lebanese artists who are now habitués of the international contemporary art scene.

For many years, Ashkal Alwan was an arts organization without an exhibition space. Residing in a flat-cum-office in Ain al-Mreisseh, Tohmé and colleagues held events in public spaces and eventually devised the Home Works Forum — a contemporary art biennial in spirit and content, but never in name, given the certainty that some contingency or another might interrupt things.

The association expanded its presence in 2011 with the opening of the Home Workspace, located in a former furniture factory near the Beirut River. The space hosted classes, workshops and lectures led by a range of Lebanese, Arab and international artists and academics, attended by an equally cosmopolitan assortment of young artist fellows. At 2,200 square meters plus a mezzanine, the Workspace was a sprawling venue by Beirut standards, with a wide common area, library and fellows’ studios as well as exhibition spaces, conference halls and administrative offices.

Much has changed in the decade since Home Workspace’s launch. Along with the rest of the country, Lebanon’s creative sector has been thrown into turmoil since 2019 by overlapping crises. In the run-up to the current meltdown, Jisr al-Wati — the former industrial zone that hosts Home Workspace, Beirut Art Center and Station Beirut — has undergone immense gentrification.

For 11 years, Tohmé, her colleagues and fellows would enter the Jisr al-Wati space “and stay there all day long, working,” she says. “It was central to the notion of the Home Workspace program as a school. People would stay there until 9 or 10 p.m. It was a completely different dynamic, having such a generous space at a time when you couldn’t afford a studio anywhere in Beirut.

“At one point we’d have 50 fellows coming in every day because everybody needed a space to work. Over its 11 years, at least 1,000 people came out of this space, with their stories, with their work and everything else. You could never do this in any other place.”

Now, she says, the Jisr al-Wati space is impossible to maintain.

“After three years of thinking what it means to be in a place, we are, like many people here, working to settle our diesel bills,” Tohmé says. Though the program occupied the Jisr al-Wati space rent-free thanks to the Association Philippe Jabre, other bills simply became too expensive. “We depended a lot on individual donations, but there are no more people supporting the arts anymore.

“Friends tell me they pay $7,000 a month just to keep their restaurants’ refrigeration operating overnight. For Ashkal Alwan [our electricity needs] start at seven in the morning and finishes at 8:30 at night. It’s not sustainable.”

A fresh start

Ashkal Alwan’s new space in Mar Mikhael was inaugurated on July 14 with two performances of a piece designed by sound artist Tarek Atoui. Titled “Waters’ Witness - Beirut,” the piece had been scheduled to be shown in Beirut in October 2019 — programmed for HW8, the eighth edition of the Home Works Forum. Like the Forum as a whole, the original 2019 show was canceled when countrywide popular protests against Lebanon’s political class erupted on October 17.

The work is the Beirut iteration of Atoui’s ongoing “I/E” project, which explores the sonic properties of international port cities. Co-conceived by Atoui and French sound artist Eric La Casa, the project is based on the artists’ recordings of activities at the docks, hangars and silos of Beirut port, documented on October 12-17, 2019. Atoui and La Casa invited deaf students from Sidon’s Orphan Welfare Society to help record the port and to “activate” the recordings in performances orchestrated by the artists.

Eric La Casa during a performance of ‘Waters’ Witness – Beirut,’ at Ashkal Alwan’s Mar Mikhael space, 14 July. (Credit: Lara Saab / Courtesy Ashkal Alwan)

Eric La Casa during a performance of ‘Waters’ Witness – Beirut,’ at Ashkal Alwan’s Mar Mikhael space, 14 July. (Credit: Lara Saab / Courtesy Ashkal Alwan)

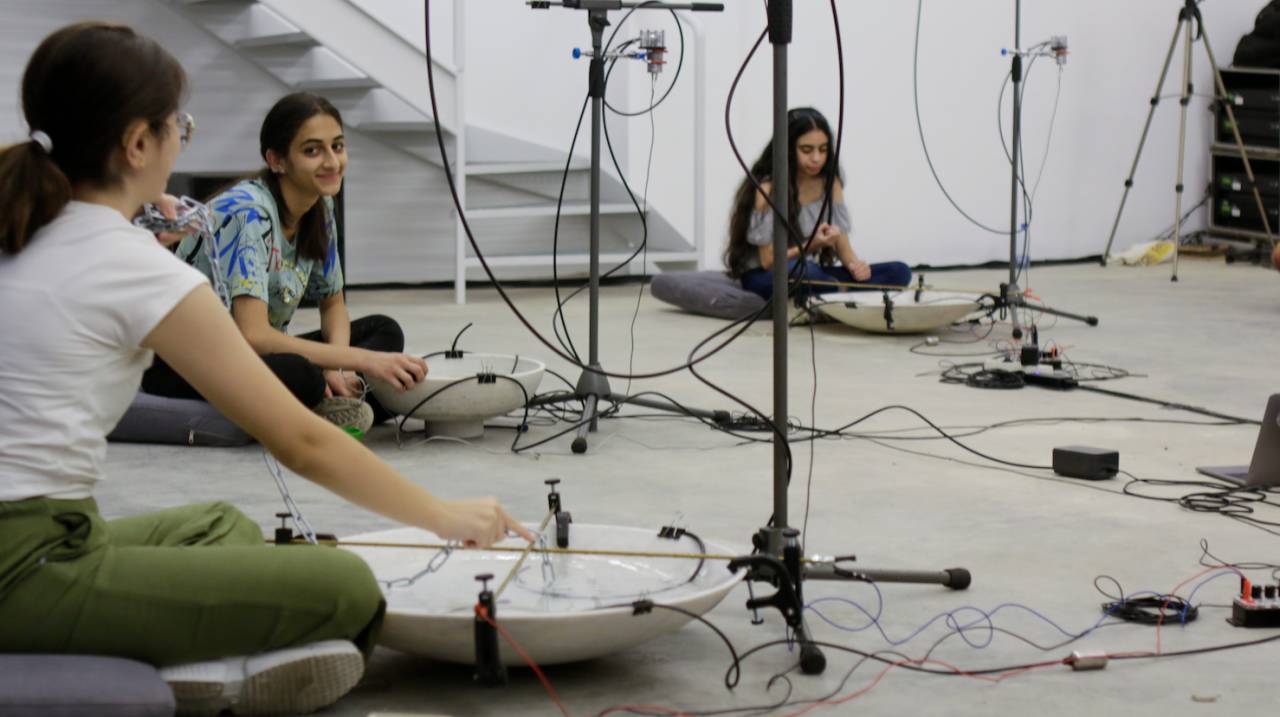

The July 14 performances reformulated the work for Ashkal Alwan’s new Mar Mikhael space. Joining La Casa (on laptop) and Atoui (on soundboard) was percussionist Akram Hajj on bass drums, cymbals and other instruments. A new group of OWS students played tailor-made electronic instruments — elaborately microphoned, water-filled stone receptacles that could be “bowed” using stones, chains and running water — which altered the recorded port sounds.

Tohmé says Ashkal Alwan remains committed to its core principles.

“We must go back to supporting artists and producing art — doing what we do and not simply protecting [our] walls,” she says. “You need to support the artists who are still here because most are definitely in need of help. These people are underprivileged and can’t travel. During the pandemic we wrote more than 400 recommendation letters for people to do overseas residencies, master’s programs or PhDs, to connect them with independent programmers. There’s an urgent need for this sort of catalyst.

“The Home Workspace program will be the same,” she adds, as the organization will move all its gear to Mar Mikhael over the next few months “Obviously it’s going to be different for everybody, since part of it is instruction, mentoring and tutoring and part of it is for the public.”

‘My main concern is to concentrate on here’

The program will now also give particular focus to the local community.

“There are people coming from the UK and the US for the residency,” Tohmé says, “but I think my main concern now is to concentrate on here. We will again host fellows for eight months. It will be completely paid. The teachers will be from here also, and from the network of people who work with us, even if they’re not here. Our HWP network is like family. They’re in France and in the States but they come [to Lebanon] all the time.”

Before Lebanon’s downward financial spiral, portside neighborhoods like Mar Mikhael and Gemmayzeh were prime real estate. Unlike at the Jisr al-Wati center, Ashkal Alwan will pay to occupy the Mar Mikhael location, though Tohmé says the rent is very reasonable.

“This building is prime real estate, but it could be demolished in eight years,” she says. “It’s completely gentrified but we’ve reached the point where this area is done. The bar business is not so interested in Mar Mikhael. It’s really shifted to Badaro. But it has a dynamic energy, and this is very important to us. It’s going to be demanding financially, but it will be less of a burden too.”

Farah Sadek, left, Yara Chehadeh, Hiba al Bathich, right — three of the six students from Saida’s Orphan Welfare Society who participated in the performances of ‘Waters’ Witness – Beirut,’ at Ashkal Alwan’s Mar Mikhael space, 14 July. (Credit: Lara Saab / Courtesy Ashkal Alwan).

Farah Sadek, left, Yara Chehadeh, Hiba al Bathich, right — three of the six students from Saida’s Orphan Welfare Society who participated in the performances of ‘Waters’ Witness – Beirut,’ at Ashkal Alwan’s Mar Mikhael space, 14 July. (Credit: Lara Saab / Courtesy Ashkal Alwan).

Tohmé smiles. “This is an old building with many beautiful, charming defects,” she says. “We must not work against it but flow with it. Though this space is smaller than the one in Jisr al-Wati, it is adaptable, she says, and close to the community that Ashkal Alwan hopes to reach.

“This space is more agile,” Tohmé says. “This is very exciting. I think there will be many kinds of events that will mingle with the neighborhood community. We’re not interested in having a set year-long program. We want to be more community responsive, say if some people need a space for a three-day conference on Lebanon’s banking sector.” Events could include community book launches, culinary workshops and others, she adds. “This is what our identity has been for the past 11 years, embedded in this educational environment. It will continue, with whatever the calamities around it have added.”

A ‘safe space’ for creativity

Tohmé says her thinking, and that of her team, itself depleted by migration, has changed.

“How do I continue? I decided I want to stay in this country. This space is one way of staying, of sustaining a kind of safe space, a sane space.

“This country, it saps every single ounce of energy you have. Every day. People need to create spaces ... where it’s about thinking about what makes you happy.” Her faces hardens. “That said, I don’t know what’s going to happen. We might have made all these plans and feel very excited, but we may still face further nice surprises.

“You can’t plan anything anymore. We have no capacity to envision things as we did — ‘This year’s program will have five workshops, five exhibitions and 10 performances.’ I don’t want to use this language anymore.”

Nevertheless, Tohmé says Ashkal Alwan will still produce Home Works next year.

“We will do it as we did before,” she says, “staged all over the city with partner institutions. It will be amazing. It will be a small Home Works, but we’ll invite people to come. We will continue doing things as much as circumstances allow. It is what it is. If it gets postponed, that’s absolutely fine.”

She beams at a group of new customers entering the café.

“You know,” Tohmé smiles, “every single Home Works has been postponed.”