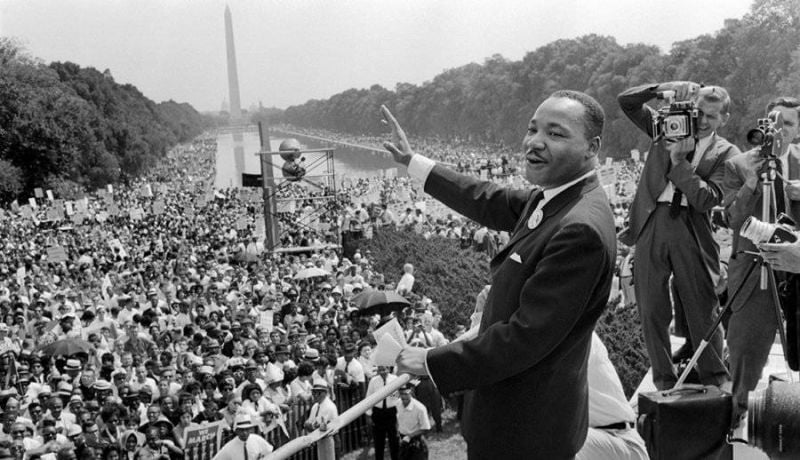

The civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. waves to supporters on Aug. 28, 1963, on the Mall in Washington, D.C., during the March on Washington. (Credit: AFP Archive)

It was the clock for me. Framed on the wall of the basement of the church, it had stopped working right at 10:22am on Sep. 15, 1963. 10:22 a.m. was when the the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was bombed. Executed by Ku Klux Klan members, the attack killed four young Black American girls. When I saw the clock, it reminded me of the thousands of clocks in Beirut where time has stood still at 6:07 p.m. since Aug. 4, 2020, when one of the most powerful explosions in history happened.

Seeing that Birmingham clock led me to think about the similarities between the African Americans’ fight for their rights and that of the Lebanese people. As a politically active member of the Lebanese diaspora who attended protests from the Chouf to Philadelphia and New York City, and who supported and worked with movements like Khaddit Beirut and Li Haqqi, I had a lot to reflect on.

There are differences between the journeys of Black Americans and Lebanese people. Blacks in the US have been subjected to abhorrent violence through slavery, segregation, lynchings, and mass incarceration, all things that we, as Lebanese people, never had to endure. But we were also subjected to injustices by our government: corruption, the vast economic inequalities in the country, the loss of our savings at banks, and the recklessness with which we are treated every day, culminating in the Aug. 4, 2020 explosion. Our lives are meaningless to the Lebanese government. This is why we have a lot to learn from the fight of Black Americans for their rights, particularly their civil rights movement.

In Lebanon, the civil society has been trying for years to change a corrupt system, but the latter only seems to be getting stronger. Many people, including myself, have lost hope that any change is possible, especially after the 2020 explosion and the way culpable political parties weathered its repercussions. But we must learn from the relentless fight of Black Americans.

While the US Constitution gave them equal protection under the law in 1868, they suffered lynching and segregation until the 1960s, and are still discriminated against today. History is long, and it's important to remember that in our fight as Lebanese people to bend history towards justice. Corruption has been part of the Lebanese political system since the country was established and it’s embedded in its people and institutions. It will be hard to eradicate it, but the key is relentlessness and patience: we must persist in our fight against corruption while remaining patient to see concrete results.

The civil rights movement in the US was a people’s movement. It had, however, a clear leadership structure at local and national levels. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led the movement nationally, but other less known figures like Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth were leading local chapters of the movement in cities like Birmingham, Montgomery and Selma. This structure helped build and grow the movement and allowed for meticulous planning. Leaders planned every detail, including the route of the marches, recruitment of new members, mass meetings, attorneys, and funds for bailing protestors out of jail. They thoroughly studied the cities they marched in, including their mayors, sheriffs, police, and people’s morale.

The civil movement in Lebanon is light years behind in these matters. While people are working hard and generously supporting the movement, lack of structure and planning is wasting these efforts and resources. Moreover, the current insistence of the opposition on a grassroots movement with no clear leader makes things confusing for many supporters. Active planning for healthy growth and efficient resource mobilization is crucial, and the Lebanese opposition needs a strong leadership figure. It’s important to elect a leader and plan long-term to efficiently recruit people, mobilize resources and progress in our cause.

To elect leadership, unity is needed. The US Black population in the 1950s was almost three times bigger than the current Lebanese population. They were diverse and had different ideas on how to tackle their problems: some were liberal, others were more conservative; some didn’t want to break any laws, others wanted to use violence; some wanted a decentralized approach, others wanted a strong center. Even within the circle of Dr. King, there was disagreement on what the movement’s priorities should be and how to address them. However, Black Americans knew what was at stake: their lives and their future. They also understood the strength of their opponent. They put their differences aside and united because they knew this was their only way to succeed.

In Lebanon, we haven’t learnt that lesson yet unfortunately. The electoral lists that were just announced for the upcoming May 2002 Parliamentary elections were another painful experience of the failure of the opposition to unite. We need unity. Previous experiences in syndicate and university elections showed us the necessity of such unity for success.

Ideological differences between opposition parties are normal. In the face of strong and well-sponsored incumbent parties, however, the opposition should unite to achieve some initial strides in our fight as a people. We should forgo small differences for the sake of our larger, sacred goal. We should unite because, like Black Americans, what is at stake is our lives and our future.

Yara Beaini is a Lebanese student at the Harvard Kennedy School and a member of Khaddit Beirut and Li haqqi.