A polling station in Beirut during the 2018 legislative elections. (Credit: Ibrahim Chalhoub/AFP file photo)

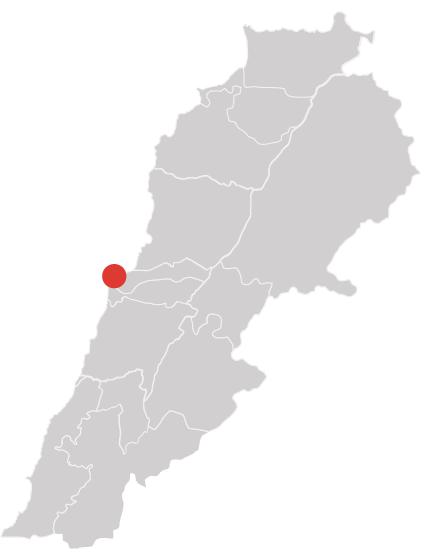

BEIRUT I

The four predominantly Christian neighborhoods of East Beirut (Achrafieh, Rmeil, Saifi, Medawar) make up this important constituency, which witnessed in the 2018 legislative elections the sole victory of civil society with the election of Paula Yacoubian to one of the eight seats — all Christian — in the constituency. The distribution of seats is as follows: three Armenian Orthodox, one Armenian Catholic, one Maronite, one Greek Orthodox, one Greek Catholic and one for Christian minorities (Syriacs, Latins, Chaldeans, etc.).

This part of the capital was devastated by the terrible tragedy of Aug. 4, 2020, which further distanced the inhabitants of these neighborhoods from the political powers in place. This part of the capital could therefore be more open to opposition candidates in May, especially since the vote threshold needed to win a seat, set by the electoral law in force, is the lowest in the country. But the Achrafieh-Rmeil-Saïfi area is also the historic stronghold of the traditional Christian parties, notably the Kataeb and the Lebanese Forces — the photo of Bashir Gemayel remains omnipresent there almost 40 years after his assassination, while the Tachnag, although present in all the neighborhoods, reigns supreme in Medawar, an Armenian stronghold if there is one.

In 2018, Gebran Bassil's Free Patriotic Movement was able to win two seats in this constituency for the first time, thanks to the new voting system. One of the major questions in the battle this year is whether he will be able to keep them.

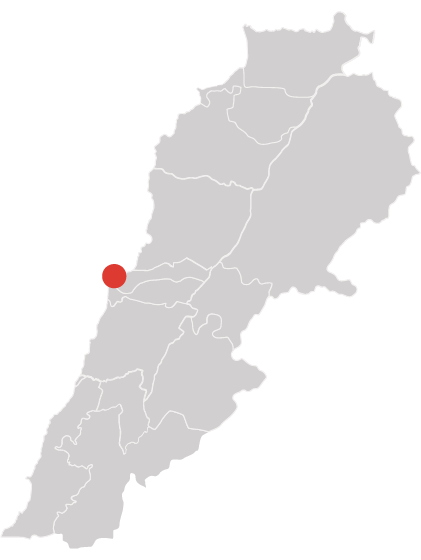

BEIRUT II

The large constituency encompassing all of the western neighborhoods of the capital, with a Sunni majority, and large Shiite and Christian minorities, has been an undisputed stronghold of the Hariri clan since the 1990s. In 2018, despite the new voting system that was clearly unfavorable to him, Saad Hariri’s Future Movement still managed (with Walid Joumblatt’s Progressive Socialist Party) to win six seats (four Sunni, one Druze and one Greek Orthodox) out of 11 in this constituency, which includes Mazraa, Moseitbeh, Bashoura, Marfa', Zoqaq al-Blat, Mina al-Hosn, Ain al-Mreisseh and Ras Beirut.

The Hezbollah-Amal-FPM alliance won four seats (two Shiite, one Sunni and one Protestant), while the last Sunni seat went to independent candidate Fouad Makhzoumi.

The withdrawal of Hariri and the Future Movement from the current elections opens this constituency to all possibilities and could strengthen the penetration of Hezbollah and its allies unless the situation is steered in a way that would remobilize the Sunni electorate around a list that is close to Hariri's choices.

The opposition movements could also make their way into this urban constituency, which, however, remains difficult to access due to a relatively high eligibility threshold.

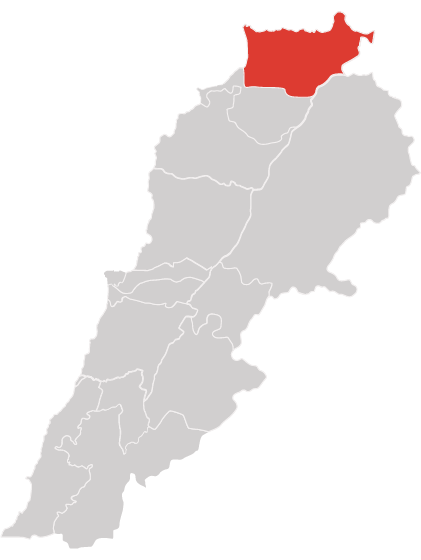

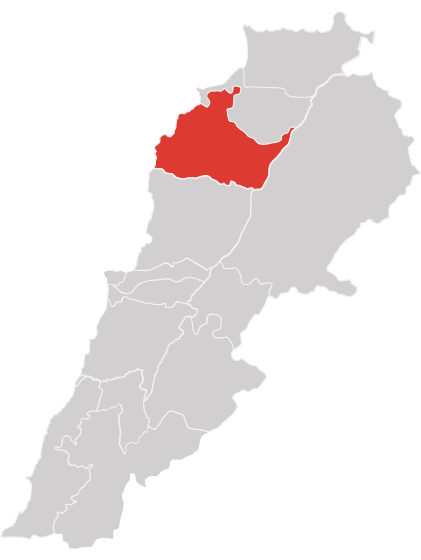

NORTH I

A real reservoir of Sunni votes, this constituency, which corresponds with the Akkar district, is one of the main strongholds of Hariri’s Future Movement. In 2018, despite a new voting system that is clearly unfavorable to it, the blue party and its allies managed to keep five seats (three Sunni, one Maronite and one Greek Orthodox), including one for the Lebanese Forces, out of seven in total. In contrast, the list led by Bassil's FPM won only two seats (one Greek Orthodox and one Alawite).

A radical change could, however, occur in 2022 if the Sunni electorate is massively demobilized due to the boycott of the election by Hariri. Moreover, in this constituency, where the large Christian minority leans more towards the FPM, the LF could lose its only seat unless it has significant Sunni support.

Added to this is the fact that Akkar is a region where in general the influence of neighboring Syria remains a factor to be taken into account.

Finally, despite a very small Shiite population, Hezbollah has been setting up an active electoral clientelism machine for several months in this peripheral region, which remains very poor and marginalized.

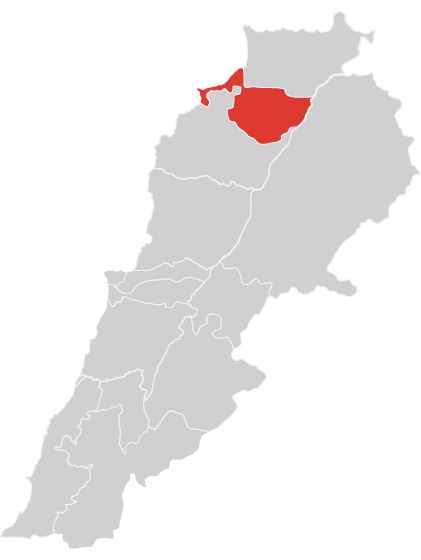

NORTH II

This large constituency is made up of the districts of Tripoli and Minyeh-Dinnieh and comprises 11 seats distributed as follows: Tripoli: eight seats (five Sunni, one Alawite, one Maronite, one Greek Orthodox); Minyeh-Dinnieh: three Sunni seats.

The city of Tripoli was at the heart of the protest movement of Oct. 17, 2019. Many will recall the huge popular gatherings that filled its public squares. What’s left of this mobilization during the legislative elections of May 15? It is still early to tell, but the fact is that few credible figures have emerged from the movement.

In the meantime, the withdrawal of the main Tripolitan political leadership figures from the elections — i.e., essentially Hariri and perhaps also the supporters of Prime Minister Najib Mikati, both winners in the 2018 elections (when the Future took five seats; Mikati, four seats; and those close to March 8, Hezbollah’s allies, two seats) leaves the situation open to all possibilities.

Former Minister of Justice Ashraf Rifi, who takes a radical attitude towards Hezbollah, could benefit from this withdrawal, as could the Sunnis of March 8 or the Islamist movements.

NORTH III

This is the constituency of all Christian battles. It is here, in this set of four districts (Batroun, Koura, Bsharri, Zgharta) with 10 seats (seven Maronites and three Greek Orthodox) that the two main Christian political leaders, Samir Geagea and Gebran Bassil, have to fight their most important battle, potentially foreshadowing the presidential elections.

It is true that the head of the Lebanese Forces is not himself a candidate for Parliament, while the head of the FMP is in Batroun. But Samir Geagea is at home in this region, as is a third important Maronite leader, Sleiman Frangieh, also a presidential candidate. The latter won three out of 10 seats in 2018, as did Bassil and Geagea. The 10th seat went to the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, an ally at the time of Frangieh. This year, the Aounist bloc must fight to keep two of its seats, having lost along the way the third, with Michel Moawad having withdrawn from their bloc to run as an independent. This will not be an easy task. The three main contenders must take into account a fourth list of weight, formed by Moawad, the Kataeb and Majd Harb, son of the former longtime parliamentarian Boutros Harb.

Finally, a fifth list, called Chamalouna, has recently emerged, bringing together opposition groups. Its results will need to be closely followed in a constituency that has many expatriates who have registered to vote.

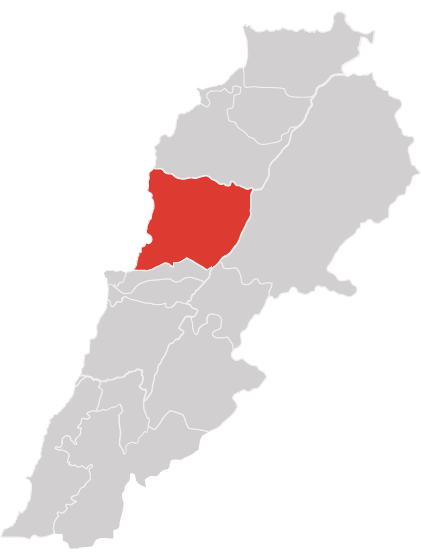

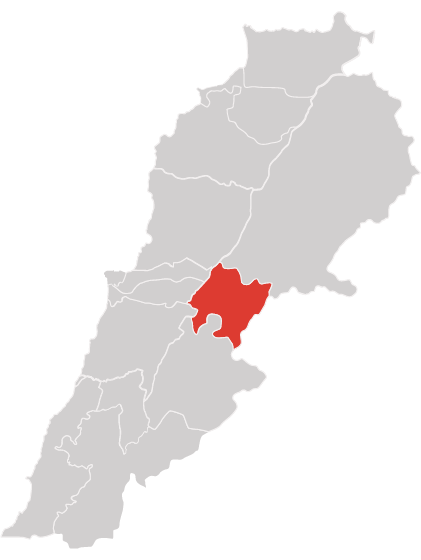

MOUNT LEBANON I

This constituency, which includes the Kesrouan and Jbeil districts, will be one of the strongholds in the battle between Gebran Bassil's FPM and Samir Geagea's Lebanese Forces.

Of the eight seats in the constituency (seven Maronite and one Shiite), the FPM and its allies had won four in 2018; the LF two; and the independent Farid Haykal Khazen (who joined Sleiman Frangieh's Marada bloc) won two as well, including the Shiite seat of Jbeil. This seat thus escaped both the candidates of the FPM and the one supported by Hezbollah, whose list did not secure the electoral threshold in this constituency.

This year, the FPM and Hezbollah seem to have agreed that the Shiite seat would go to Hezbollah in exchange for a Christian seat in Baalbeck-Hermel for the FPM. But with this gain, Bassil's party can no longer count on the alliance with the businessman Nehmat Frem, nor with the ex-officer Chamel Roukoz, who is a son-in-law of President Michel Aoun like Bassil but is a declared opponent of the latter.

The battle is therefore very open in a region where, especially in Kesrouan, family considerations play an even more important role than political affiliations.

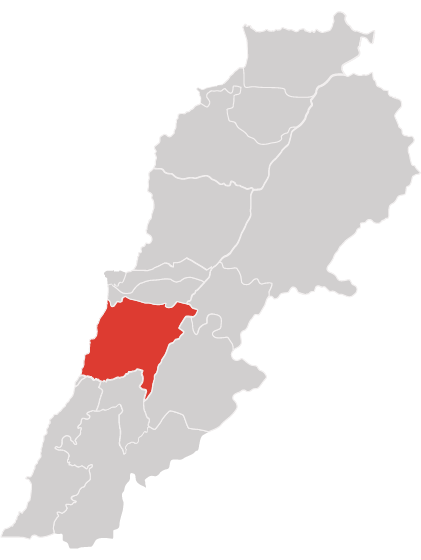

MOUNT LEBANON II

The constituency is the Metn district. It has eight seats: four Maronite, two Greek Orthodox, one Greek Catholic and one Armenian Orthodox. It is a stronghold of the Aounists, Sami Gemayel's Kataeb, Tachnag and former MP Michel Murr, who died last year. But the Lebanese Forces also have a strong presence there, even if in this region, which is rather atypical in this respect, their influence is less pronounced than that of their Kataeb rivals.

The latter, who have had two seats in this constituency since 2018, are preparing an alliance with some of the civil protest movements this year, in a joint list. The chances of this list to reach three electoral thresholds (and therefore three seats) are thus clearly strengthened, and this could be at the expense of the FPM and its allies.

Including Tachnag, the outgoing Aounist bloc has four seats. Will it be able to keep the same number of seats in the new Parliament that will result from the May 15 elections? The answer to this question depends on many factors: the Kataeb and the civil society groups, of course, the score of the LF, which this time has doubled the stakes by aiming for two seats instead of one, and on what the successor of Michel Murr will do.

MOUNT LEBANON III

Three Maronite seats, two Shiite and one Druze: a total of six seats are allocated to this constituency, which merges into the district of Baabda, or Metn-South. This is made up of two quite distinct regions: on the one hand, the coastline that covers the predominantly Christian (southeast) and Shiite (south) suburbs of Beirut, and on the other hand, the Druze-Christian mountain (upper Metn).

Until now, the constituency has been an Aounist stronghold, with the presence of a strong Shiite minority helping the FPM consolidate its hold on the three Christian seats in the district. But in 2018, thanks to the new voting system, Bassil's party lost a seat to the Lebanese Forces. In 2022, the prospect of losing a second seat due to the general decline in public opinion of the party led Bassil to cut loose the weak link of the Aounist party in the region, outgoing MP Hekmat Dib. The latter reacted by walking out of the FPM.

If this second seat is indeed lost, knowing that that of MP Alain Aoun is more or less guaranteed, who will benefit from it? There are two possibilities: it will either be a candidate from the powerful LF-PSP list or a representative of the opposition from the civil protest movement, which is preparing, with the likely support of the Kataeb, to form a viable list.

On the Shiite side, the Hezbollah-Amal tandem traditionally share the two seats; while it is very easy for Hezbollah to secure the seat, it is a harder task for Amal, but still guaranteed so far.

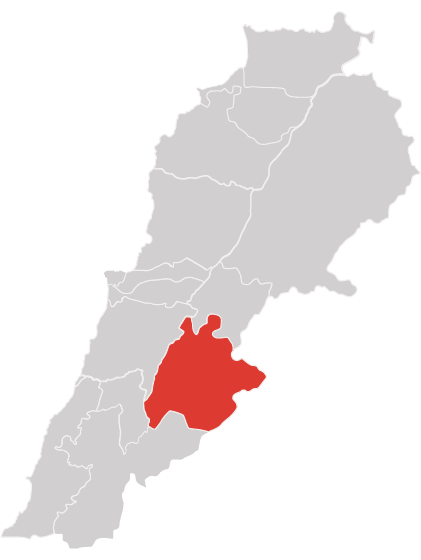

MOUNT LEBANON IV

This is the largest constituency in the country in terms of number of seats (13). It consists of the districts of Chouf and Aley and a stronghold of Jumblatt par excellence. In total, it includes five Maronite seats, one Greek Orthodox, one Greek Catholic, four Druze and two Sunni.

In 2018, the alliance list of the PSP and its allies, the Lebanese Forces and the Future Movement won nine seats out of 13. On the other hand, thanks to the proportional representation system, the FPM, which has a strong presence in the region, was able to grab three (Maronite), while the last (Druze) seat went without a battle to Talal Arslan, Walid Joumblatt's rival but to whom the latter traditionally grants one of the two Druze seats in Aley, by refraining from presenting a candidate against him.

This year, the Joumblatt’s party and the LF have again joined forces against the Aounists, but the Future Movement is missing. This is a fundamental fact, as Sunnis constitute a good third of the electorate in the Chouf. A massive demobilization of the pro-Hariri camp can only weaken, even if partially, the PSP-LF alliance.

In addition, it will be necessary to take into account the performance of the civil protest movement. In 2018, some activists individually obtained acceptable scores, but divisions in the ranks of civil society prevented them from influencing the vote in this constituency.

BEKAA I

It is in this constituency, which corresponds to the district of Zahle, that an MP was elected with the lowest numbers of votes in 2018: the Armenian Orthodox Eddy Demerdjian, who became an MP with only 77 preferential votes. This is a perverse effect of the current voting system: the list supported by Hezbollah, of which Demerdjian was a member, had reached twice the electoral threshold (so it should be granted two seats), but apart from the Shiite candidate, no other member of this list was able to beat his direct competitors in the other lists. As a result, the remaining votes in favor of the Hezbollah list went to the Armenian Orthodox candidate, as all other seats were already taken.

Zahle has seven seats distributed as follows: two Greek Catholic, one Maronite, one Greek Orthodox, one Armenian Orthodox, one Sunni and one Shiite. In 2018, the traditional leadership of the Skaffs had its twilight there, as the widow of former MP Elie Skaff failed, along with her entire list. The general context is not yet completely clear this year, but some fundamental data points are already palpable: the probable demobilization of the important Sunni Hariri electorate, ally of the FPM in 2018, and the exit of the independent MP Michel Daher from the Aounist parliamentary bloc are likely to weaken the position of Gebran Bassil’s party, in the face of a possible rise in power of the Lebanese Forces. It is true, however, that Hezbollah's support for the FPM could partly compensate for these losses.

BEKAA II

It is in this constituency, which is supposed to be more or less locked down by the Hariris and their allies, that the Future Movement showed the most vulnerability in 2018 due to the new voting system based on proportional representation.

Covering the Bekaa West-Rachaya districts and with six seats (two Sunni, one Shiite, one Druze, one Maronite, one Greek Orthodox), the constituency was the scene of a classic battle between the Future-PSP list and another March 8 list. In the end, the two lists won equal seats (three for each), but in a symbolic defeat for Hariri, the list close to March 8 came out on top in terms of votes, ahead of its rival by a few hundred.

This year, the political context remains unclear, especially with the exit of the Future Movement. A strong alliance between the Shiite tandem, the FPM and the pro-Syrian Sunnis is not to be ruled out, which could allow these parties to win. In this context, there is already talk of a rapprochement between Deputy Parliament Speaker Elie Ferzli, who has the Greek Orthodox seat, and the Aounists. On the other hand, if such a configuration is confirmed, and unless there is a Sunni mobilization, only the outgoing Joumblattist Wael Bou Faour would be more or less assured of playing his cards right; his score alone in 2018 was almost equal to the electoral threshold.

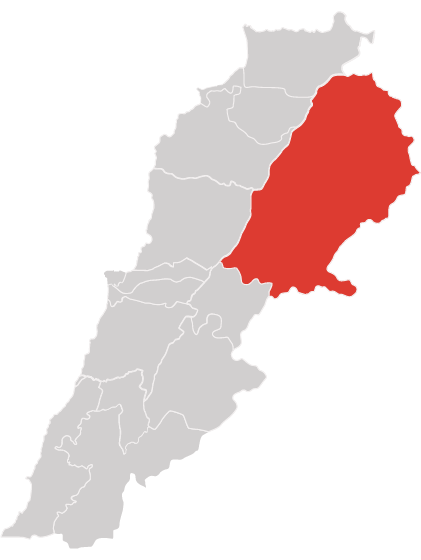

BEKAA III

The Baalbeck-Hermel constituency, with 10 seats (six Shiite, two Sunni, one Maronite, one Greek Catholic) is an undisputed Hezbollah stronghold. However, Hezbollah, along with its allies, won "only" eight of the ten seats in the 2018 elections, due to the voting system, allowing one of the Sunni seats to go to the Future Movement and the Maronite seat to the Lebanese Forces. On the other hand, it easily retained all six Shiite seats, and won one Sunni seat and the Greek Catholic seat.

This year, there should be no major upheaval in the region, as Hassan Nasrallah's party seems far from losing its dominant position. The question that arises is whether, deprived of Sunni support, the outgoing LF MP Antoine Habchi will be able to keep his seat. Given the more than respectable score he achieved individually in 2018 (nearly 15,000 votes out of a threshold of 18,700), the task is far from being impossible. The second issue lies in the probable entry of the FPM in this region, an agreement having apparently been reached with Hezbollah on the Greek Catholic seat, currently held by Albert Mansour, who is close to pro-Syrian circles, to be attributed to Bassil’s party. It would in fact be a give and take between the FPM and Hezbollah, as the latter would take the Shiite seat of Jbeil in return.

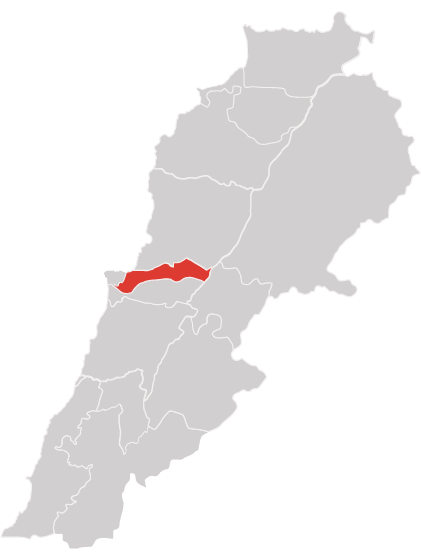

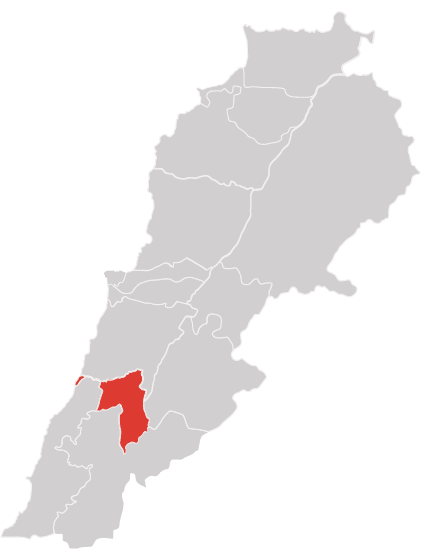

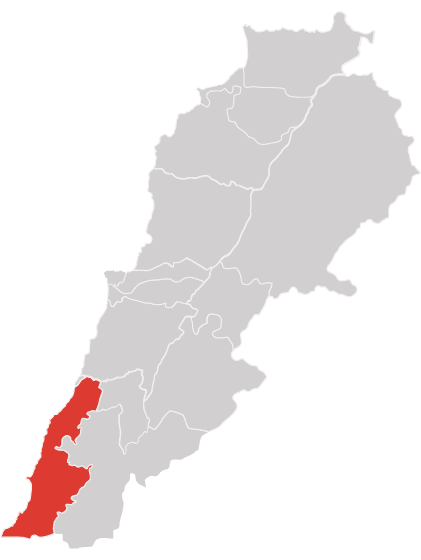

SOUTH I

This constituency is atypical in the sense that it is the only one without geographical continuity. It is made up of the city of Saida, detached from the Zahrani region, and the district of Jezzine, and has five seats (it is the smallest constituency in the country): two Sunni, two Maronite and one Greek Catholic.

The absence of a Shiite seat in this constituency should not be deceiving regarding the influence that the Amal-Hezbollah tandem has there. Not only does the Shiite electorate — which is a minority, but decisive at the same time — play the role of a referee, but the parliamentary bloc of Speaker Nabih Berri claims a Maronite seat in Jezzine, that of MP Ibrahim Azar. In 2018, the latter had wrested this seat in a battle between Amal and the FPM, and it is clear that the Hezbollah electorate had decided the duel in favor of the former. This year, an agreement is in the making to maintain the same result in Jezzine; i.e., two seats for the FPM and one for Berri’s bloc.

In Saida, the battle is open. Two basic facts impose themselves: first, the withdrawal of the Future Movement, implying a demobilization, unless there is a resurgence, and the end of the alliance between the outgoing MP Osama Saad and the duo of Hezbollah and Amal. Since the Oct. 17, 2019 uprising, Saad has distanced himself from the March 8 bloc, moving inexorably closer to the opposition movement.

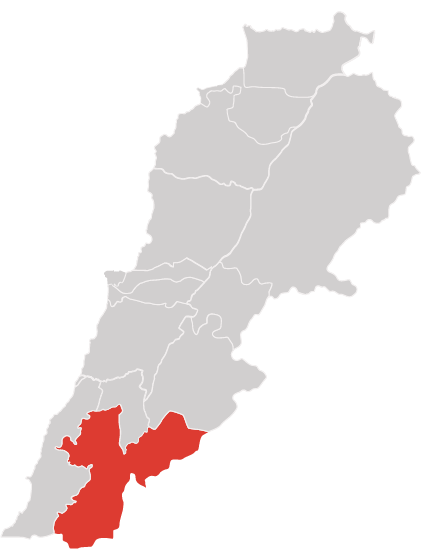

SOUTH II

This is a constituency in which the Shiite parties, Amal and Hezbollah, absolutely dominate the field.

The constituency is the stronghold of Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, and has seven seats: six Shiite and one Greek Catholic. The small number of seats compared to the large number of registered voters in this entity means that the electoral coefficient is particularly high (more than 21,000 in 2018), which has a prohibitive effect on any potential competitor of the two Shiite parties.

The situation is not expected to change in 2022. However, it will be interesting to examine the scores of a possible protest list from Oct. 17, 2019 popular protest movement as the city of Sour was one of the sites of the uprising, although the movement developed more timidly in the city than elsewhere in the country, possibly due to the hostile environment.

Another minor issue to follow is the performance of Amal’s candidates compared to Hezbollah’s. In 2018, while Berri came out on top of the polls by a wide margin, garnering the equivalent of a little more than two electoral coefficients on his own, the other Amal candidates closed the pack, largely outpaced by their Hezbollah colleagues. But it is true that by prior agreement between the two parties, the latter aligned only two candidates against the five of the Berri movement. As a result, the Hezbollah vote was more concentrated.

SOUTH III

A Shiite ocean even denser than the previous constituency of South Lebanon II, this group includes the districts of Nabatieh Bint Jbeil, Marjayoun and Hasbaya, the last two being predominantly Druze, as well as Baalbeck-Hermel and Rachaya-West Bekaa. However, the electoral configuration is not quite the same as in South II, due in particular to the presence of a Sunni-Druze-Christian island in the Marjayoun-Hasbaya area. Therefore, on paper at least, the rule of the Amal-Hezbollah alliance is not as absolute as elsewhere. To this, it must be added that the Communist Party retains a significant base in many Shiite localities in the region.

The results of 2018 elections show that if, instead of the five lists that participated in the election against the steamroller of the two Shiite parties, there was only one, at least one electoral coefficient would have escaped this tandem and there would have been one less seat won by Hezbollah or Amal.

But this is purely an arithmetic speculation, as the ability to form a unified and solid list against the Shiite tandem on its own land is not easy, for obvious security and other reasons. Sectarian and partisan egoism, rivalries between allies and, more generally, the political fragmentation of the country hardly facilitate the dynamics of unity, and this is visible everywhere, even in the ranks of the protest movement.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.

The four predominantly Christian neighborhoods of East Beirut (Achrafieh, Rmeil, Saifi, Medawar) make up this important constituency, which witnessed in the 2018 legislative elections the sole victory of civil society with the election of Paula Yacoubian to one of the eight seats — all Christian — in the constituency. The distribution of seats is as follows: three Armenian...