Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament Nabih Berri is among nine incumbents running for reelection who have served in every Parliament since at least 1992. (Credit: AFP archive photo)

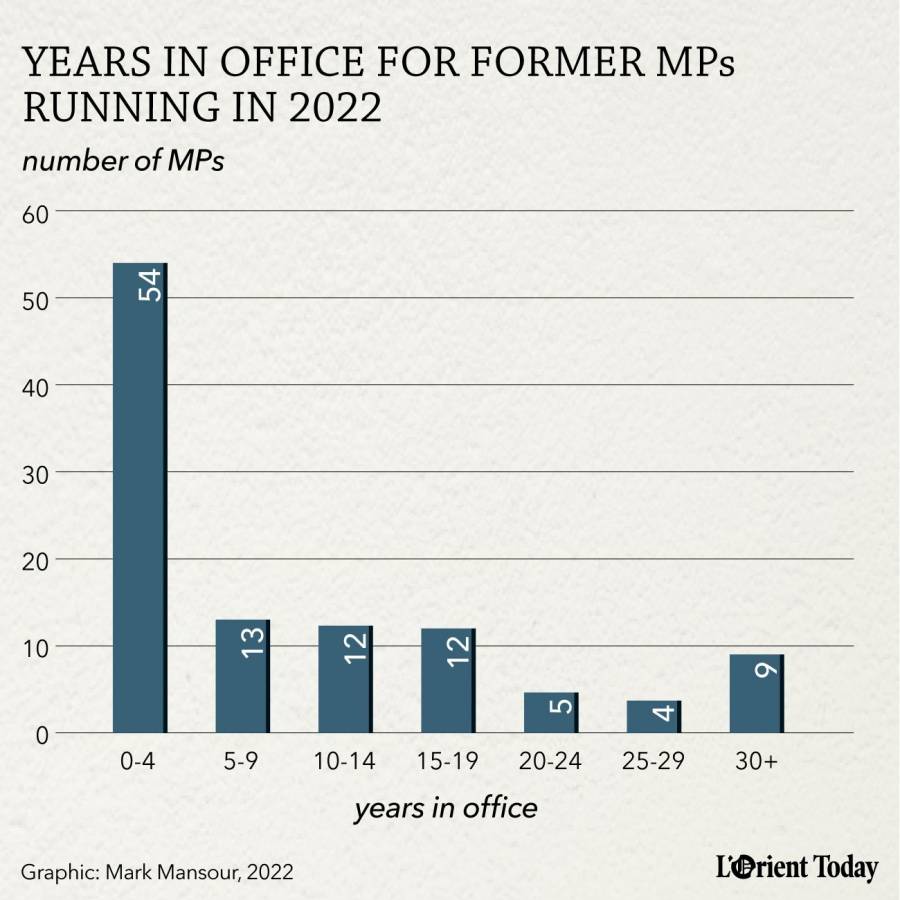

BEIRUT — Ninety members of the current Parliament are candidates in the upcoming elections, an analysis by L’Orient Today shows. They are joined by an additional 19 former MPs who served in Parliament between 1992 and 2018, meaning that in all, L’Orient Today has found 109 current or former MPs among the 1,043 candidates registered for the May 15 polls, after an analysis of election records dating back to 1992.

Despite several high-profile Sunni politicians boycotting the election, the 90 sitting MPs seeking re-election this year are a larger number than in 2018, when only 74 members of the then-sitting Parliament sought re-election. Between 2009 and 2018 four deputies died in office, making them unable to run for reelection; three of them were replaced during the legislative term and are included among the 74 who ran in 2018.

The number of deputies seeking re-election in 2022 is slightly below that of 2009, when 99 sitting MPs sought to renew their mandate. The vast majority of them, 81, were successful in returning to Parliament that year. In 2018, on the other hand, just 50 members of the previous Parliament returned to office out of the 74 who tried, perhaps a product of the changes brought about by the 2017 electoral law that transitioned from using bloc votes for the whole list to preferential votes. Still, in 2018 the re-elected MPs were joined by seven returning MPs from the 2005 Parliament and eight from even earlier ones, meaning that first-time deputies still made up less than half the chamber.

Among the incumbents running for re-election this year, nine have served in every Parliament since at least 1992, meaning they have spent 30 or more consecutive years in the legislature.

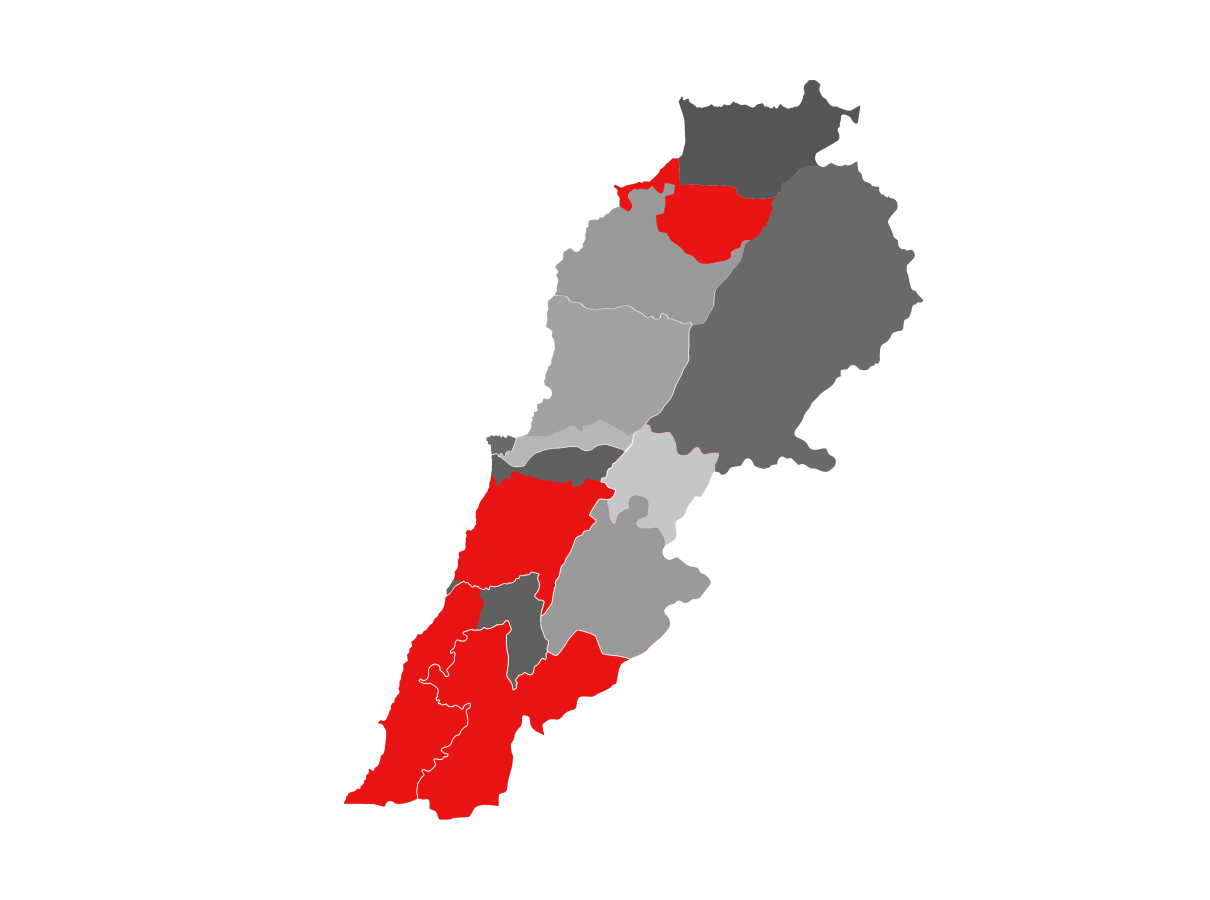

They are: Akram Chehayeb (Aley), Ali Osseiran (Zahrani), Assaad Hardan (Marjayoun-Hasbaya), Ayoub Hmayed (Bint Jbeil), Marwan Hamadeh (Chouf), Michel Moussa (Zahrani), Mohamed Hassan Raad (Nabatieh), Mohamed Kabbara (Tripoli), and Nabih Berri (Zahrani).

Districts containing an MP who has served for at least 30 years.

Districts containing an MP who has served for at least 30 years.

A further nine MPs running for office have served between 20 and 30 years each: Ali Hassan Khalil (Marjayoun-Hasbaya), Ali Yousef Khreis (Sour), Ghazi Zeaiter (Marjayoun-Hasbaya), Hussein Hajj Hassan (Baalbek-Hermel), Ali Ammar (Baabda), Kassem Hachem (Marjayoun-Hasbaya), Mohamed Hajjar (Chouf), Talal Majid Arslan (Aley), and Estephan Douaihy (Zgharta).

The fact that so many members of the political class are seeking re-election may seem baffling after more than two years of one of the modern world’s worst economic crises, political gridlock, and the loss of legitimacy associated with the Oct. 17, 2019 protests and the Aug. 4, 2020 Beirut port explosion. An Arab Barometer survey in March and April 2021 found that 96 percent of Lebanese were “dissatisfied” or “completely dissatisfied” with their government.

But, for Ali Taha, a researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, the high number of incumbent candidates is no surprise.

“We have to understand that this political elite has been involved in corruption for years. This is always the case in regimes where corruption has riddled government institutions,” he explained. “We see that people in power are very reluctant to leave office because they know that once they do, they’ll be held accountable.”

Taha expressed skepticism that incumbents are ideologically driven and are running for office because they believe themselves to be the best people to lead the country out of its crises.

“In the case of Lebanon, I think the political elite is aware of their incompetencies … it’s just self-preservation,” he said.

Bassel Salloukh, a political scientist at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, sees a message being sent by the leaders of the establishment parties as they re-nominate the same individuals as before the crisis.

“What they want to do with this election is to use the election to reproduce their ‘legitimacy’ and to reproduce the ‘legitimacy’ of the sectarian political system,” he said. “For the leaders of the sectarian political system, running most of the same faces is their way of saying, ‘We’re here and we’re going to contest these elections and we’re going to use these elections to reproduce our legitimacy and to show our representativeness of the population.’ That’s why we shouldn’t be surprised that a lot of the old faces have been included.”

The identity of individual deputies is widely thought to be less important in Lebanon’s political system than the grand bargaining that takes place between the handful of sectarian leaders and the last-minute electoral alliances they form in each district.

The 2017 electoral law replaced bloc votes for lists with a preferential vote system that has made list formation more complicated. It also made the individual profiles of candidates more important, according to Salloukh, because of the focus on the number of preferential votes that each candidate can bring to the list.

Individually and via their parties and sectarian patrons, incumbents in Lebanon have large advantages over their rivals. Having control over state resources like public sector job opportunities gives them the ability to reward loyal voters and build patronage networks. Access to the media, or in some cases control of the media, gives them a platform to communicate with voters that is rarely matched by outsiders and emerging parties. They also have valuable experience in navigating the complicated arithmetic of distributing preferential votes among candidates on the list to maximize results and established relationships with electoral “keys”—people who mediate between candidates and blocs of voters.

Whether or not the advantages held by incumbents are outweighed by the prevailing hostility among voters towards the existing political class remains to be seen. With 109 postwar deputies on the ballot this year, over a quarter of the nearly 400 people who have served in Parliament since 1992, the stage seems set for the election to function as a referendum on their accomplishments in power.

But the establishment parties are eager to avoid the perception that the election is about their performance in power, according to Salloukh. He said the coming weeks could see intensifying sectarian narratives that blame the crisis on Hezbollah, Syria, and Iran, on the one side, or America, Israel, and Gulf on the other; both narratives being calculated to preclude, he said, the emergence of an accountability narrative that implicates all of the parties.

“What they’re all trying to avoid is engagement with the idea that ‘you all have been involved in the political system if not from 1990 then certainly from 2005.’”

Correction: An earlier version of this article said 91 current MPs are candidates in the election. The correct number is 90.