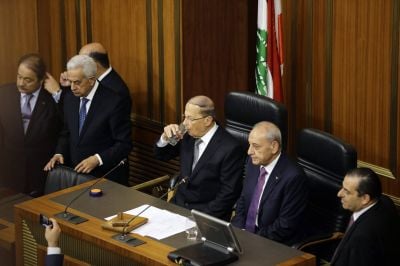

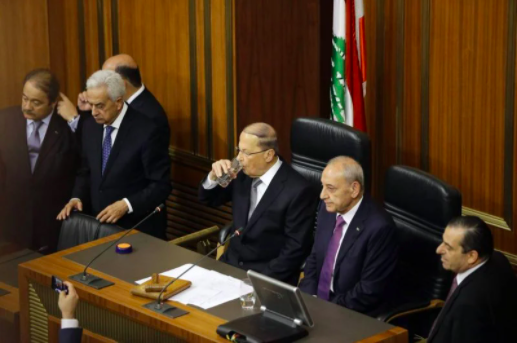

Newly elected President Michel Aoun drinking a glass of water near Parliament Speaker Nabih Berry after being sworn in, Oct. 31, 2016. (Credit: Joseph Eid/AFP)

He had been waiting for this moment all his life. On Oct. 31, 2016, Michel Aoun would be officially elected as president of the republic.

After almost three years of a presidential vacuum, the former army general finally made his dream come true through a political compromise.

It was going to be him “or no one,” Aoun had warned from the very start, wielding the support of his powerful ally Hezbollah, which was ready to paralyze the country to offer him his most coveted prize.

Almost all the other leaders came to accept this reality. Almost all of them promised that their MPs would vote for Aoun, including Samir Geagea, the president’s previous nemesis and the leader of the Lebanese Forces, who rallied around the idea that the “strongest Christian” should win the day.

Even Saad Hariri, who for years had been flayed by Aoun, ended up becoming a key partner in the so-called “presidential compromise.”

Almost all, except Nabih Berri.

There is no one in the entire country the head of Parliament hated more than Aoun— a feeling shared by the Christian leader — and he had sworn that he would never let him ascend to the presidency.

But on Oct. 31, 2016, it was already too late. Berri knew he lost this round. Not one to admit defeat, the speaker was already preparing for what was coming next.

Berri made sure to take advantage of the fact that the inauguration of his archenemy as president took place in his own playground — the parliament of which he has been head for 25 years — to set the tone for the battle to come.

This was supposed to be Aoun’s day. Berri would make sure to ruin it for him.

In the first round of voting, the ex-army commander and founder of the Free Patriotic Movement obtained 84 votes. He needed two more to get the two-thirds majority necessary for his election.

In the second round, he needed an absolute majority of 65 MPs, which was only a matter of formality for Aoun to secure his return to Baabda, 26 years after being driven out by the Syrian army — a return that he must have imagined thousands of times.

It was time to count the ballots. Aoun held his breath. There were 128 pieces of paper. The only problem was that, with the resignation of Robert Fadel, Parliament had only 127 members.

MPs had to vote again. The result was the same, 128 votes. Aoun began to turn red. His face twitched. He imagined the worst. At the moment, he had no doubt that Berri was playing with his nerves.

The Amal head allegedly asked one of his deputies to slip two ballots into the ballot box to create confusion.

Aoun had to endure another round of voting to finally savor his victory. “The hour of great jihad has come,” Berri allegedly said just after the election.

War was declared.

‘My ally’s ally’

For 30 years, there has been an underlying rivalry between the two men, which culminated when Aoun ascended to the presidency — a development that called into question the balance of power. No rivalry between two leaders within the Lebanese political establishment has continued for so long or burned so intensely.

Aoun’s relationship with Geagea had its ups and downs, but not with Berri. Both leaders made Hezbollah their main ally and were considered on the same side, that of the pro-Syrians, for years.

But even at the height of the coalition of March 8 forces, both men saw each other as “my ally’s ally,” each seeking to pull Hezbollah further to his side, and having it, ultimately, all to himself.

In theory, Aoun and Berri should have gotten along. Both hailing from modest backgrounds, they embodied a form of middle-class rebellion against the aristocracy of their respective communities.

The first took power through the army, the second through militia. Are these two irreconcilable trajectories? In the 1980s, they certainly were.

Berri took over the leadership of the Amal Movement in 1980, two years after the disappearance of Imam Moussa Sadr in Libya. Meanwhile, Aoun was appointed commander-in-chief of the army in July 1984.

A few months earlier, on Feb. 6, Berri launched an offensive with Walid Joumblatt to retake the neighborhoods of West Beirut. This would be the main confrontation between the two men throughout the civil war.

In the 1980s, the animosity between the two was still in its early stages.

Each of the two men was preoccupied with the battles within their own camps. Berri against the Palestinians and against Hezbollah. Aoun against the Lebanese Forces.

The Amal leader was seeking to take advantage of his good relations with Syria to allow the Shiite community, which had been historically marginalized in the country, to play a leading role in Lebanese institutions.

Meanwhile, the army chief defended the state, which meant getting rid of the existing militias.

Berri wanted to be the symbol of the “Shiite renaissance,” Aoun the protector of “Maronite Lebanon,” two fundamentally incompatible projects which would come at loggerheads during the conclusion of the Taif Agreement in 1989, which ended the 1975-90 Civil War and redistributed powers to the detriment of the Christians. It was slammed by Aoun.

Initially opposing the deal, arguing that it was not fair to the Shiites, Berri ended up being one of the main beneficiaries of the agreement. Aoun was one of the biggest losers.

The then-army general launched a “war of liberation” against the Syrians which he lost. His time was over.

On Oct. 13, 1990, the Syrian army took over the Baabda presidential palace, where Aoun had ensconced himself. Aoun was forced into exile in France.

The troika

This was the beginning of a new chapter of resentment and desire for revenge.

In 1992, Berri was appointed head of Parliament, while Lebanon was under the tutelage of the speaker’s political patron, Syria. In a span of a few years, the former militiamen became the most powerful figures in the country.

Christians had almost disappeared from the political arena with Aoun in exile and Geagea in prison.

In addition to the Syrians, who were still the masters of the game, Berri shared power with other political forces, notably the Sunni Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, and the Druze leader Walid Joumblatt.

Meanwhile, Aoun was champing at the bit and plotting his revenge. He would have to wait 15 long years before being able to set foot in Lebanon again in 2005, following the departure of Syrian troops.

The general wanted to end what began with the Taif Agreement.

Aoun fiercely opposed the ruling troika of Hariri, Berri and Joumblatt, whom he accused of having shared the cake to the detriment of Christians. In his mind, Berri stole the state from Christians by taking control of key positions.

In 2005, the electoral battle was launched. Despite the mass protests of March 8 (pro-Syria) and March 14 (anti-Syria), in the wake of the assassination of Rafik Hariri in February of the same year, Berri managed to convince Hezbollah to ally itself with the Future Movement and Joumblatt’s Progressive Socialist Party against Aoun.

While the other stakeholders preserved their positions, the Christian leader emerged as the biggest winner from the elections. His comeback was a success.

His ambitions, however, were thwarted by his inability to forge alliances on the local scene. On Feb. 6, 2006, Aoun changed the equation by making Hezbollah his main ally, which was a game-changer.

The Shiite party, which was still not very involved in the state, was not the target of the then FPM leader’s “anti-establishment” discourse. On the contrary, Hezbollah would even become Aoun’s springboard to power.

On the other side of the alliance with Hezbollah, Berri was livid. Aoun was a direct threat to him, much more than his March 14 opponents.

Not only did he want his share of the pie, which automatically cuts the share of others, but he was also attacking the corruption, the small arrangements and clientelism that Berri embodied in the eyes of his supporters.

For almost 10 years, the conflict between the two remained latent. The standoff between the camps of March 8 and March 14, and the war in Syria were at the forefront of the nation’s political space.

‘I don’t want to irritate Aoun’

In 2016, the conflict became more direct. Aoun wanted the presidency at all costs and had Hezbollah’s support all the way. Berri swore to do everything in his power to make sure that it did not happen.

When he finally understood that there was nothing he could do, and that Hariri and Aoun had already made a deal, Berri held a dialogue in his residence in Ain al-Tineh in September of that year. He did not want to get left behind.

For him, all subjects must be addressed within the framework of an overall agreement in relation to the electoral law, the government and economic issues.

On the Aounist side, it was Gebran Bassil who attended the discussions. The president’s son-in-law, whose stature in the political arena had been growing since Aoun’s return in 2005, was certainly aware of Aoun’s faltering relations with Berri.

Bassil rejected the speaker’s proposal. There was no question of concluding one “big deal.” The conversation took a different tone. Bassil then said the discussion was over.

“I was the one who called for this dialogue and it’s me who decides when it ends,” Berri replied. No one normally allows themselves to challenge his authority, let alone a man half his age.

“That day, Berri was convinced that Aoun was coming to power with the desire to eliminate him politically," a source close to the speaker said.

Meanwhile, a source close to Aoun said, “He never liked the idea of Christians being represented by a strong president capable of defending their prerogatives.”

The battles would unfold, to Aoun’s advantage, at first. The president had the support of Hezbollah, and an alliance with Hariri.

The parliament speaker was in a weak spot. He complained about it to the Sunni leader.

“What are you doing? You are giving everything to Michel Aoun,” Berri allegedly told Hariri. “I don’t want to irritate him,” Hariri replied.

In 2018, Bassil crossed a line when he was heard in a leaked video accusing Berri of abusing power, and then calling him “baltaji” which means “thug.”

Tensions were running high. Berri, the powerful Parliament speaker, the former warlord, could not be insulted like this without reacting.

Amal supporters took to the streets, cut roads, burned tires and shot in the air. But all this was not enough to hide the obvious: Berri was no longer as strong as he used to be.

Bassil, who was at the same time the unofficial “vice-president” and “deputy prime minister,” given his close ties with both Aoun and Hariri, knew this better than anyone. Even Hezbollah did not lift a finger to defend Berri.

‘We will not let him’

The Oct. 17, 2019, uprising came to change the entire equation. Berri was booed in the streets, but not as much as Bassil.

While the old veteran had seen his share of popular uprisings, the presidential camp saw its mandate turn into a nightmare. Popular anger grew even stronger against the president when Hariri stepped down.

Aoun felt besieged. He was convinced that the troika ganged up on him, with LF support. A showdown over every issue was almost inevitable.

The president restarted negotiations on the demarcation of the maritime border with Israel right under Berri’s nose.

He also wanted the head of the central bank governor, Riad Salameh, who is close to Berri and the ideal scapegoat for the crisis in the eyes of the Aounists.

But the former lawyer would not have it. With the support of the banks, Salameh and Hariri, Berri paralyzed the government of Prime Minister Hassan Diab, whom he did not want to see as the head of government. Diab, however, had Aoun’s support.

The speaker regained the upper hand. Aoun tried to take down his finance minister but to no avail. He sought by all means to prevent the return of Hariri at the head of the government. He failed again.

But Aoun is tenacious and did not cave in.

Hariri failed to form a cabinet and was forced to step down. The war flared when Najib Mikati took office. Hezbollah found itself torn between its two allies. But blood ties are stronger than anything else.

The political context had changed and Aoun was weakened, being increasingly blamed by his supporters for his alliance with the Iran-linked party.

Hezbollah and the Amal Movement wanted to see Tarek Bitar, the lead investigator in the Beirut port explosion probe, out of the picture. They considered him to be biased and his investigation “politicized.”

Aoun was not ready to sell Bitar out if he did not get anything in return.

“He wants two essential things: he wants to see some of his people appointed in the judiciary, security, administration and diplomacy sectors in order to guarantee his share in the state before leaving Baabda. And an endorsement for his son-in-law for the presidential elections,” a source close to Berri said.

“In both cases, we will not let him,” he added.

For weeks, both sides have been at odds over the upcoming legislative elections, notably on the election date and the vote of Lebanese citizens living abroad.

Aoun was finally able to have the last word on the election date, but lost the round on the vote of the Lebanese diaspora, which could cost him very dearly.

Dirty laundry was now aired in public. At the beginning of January, Bassil directly attacked the Amal movement, accusing it of being the evil genius in his alliance with Hezbollah.

The next day, former Finance Minister Ali Hassan Khalil, Berri’s most faithful man, snapped back. The two accused each other of being corrupt to the core.

Now, a few weeks from the elections, tensions are as high as the stakes for the two rivals. The challenge now is to survive, but above all to survive each other.

The president has already threatened to not leave the Baabda Presidential Palace at the end of his term if there is no consensus on his successor.

He refuses to leave power knowing that Berri will remain at the head of Parliament. The latter does not intend to leave his position before he dies.

During his first meeting with a western ambassador a few years ago, Berri summed up his vision of Lebanon.

“I will explain to you how our country works. The president must be a Maronite, the prime minister always a Sunni, and the Parliament Speaker must always be… Nabih Berri,” he allegedly said.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.