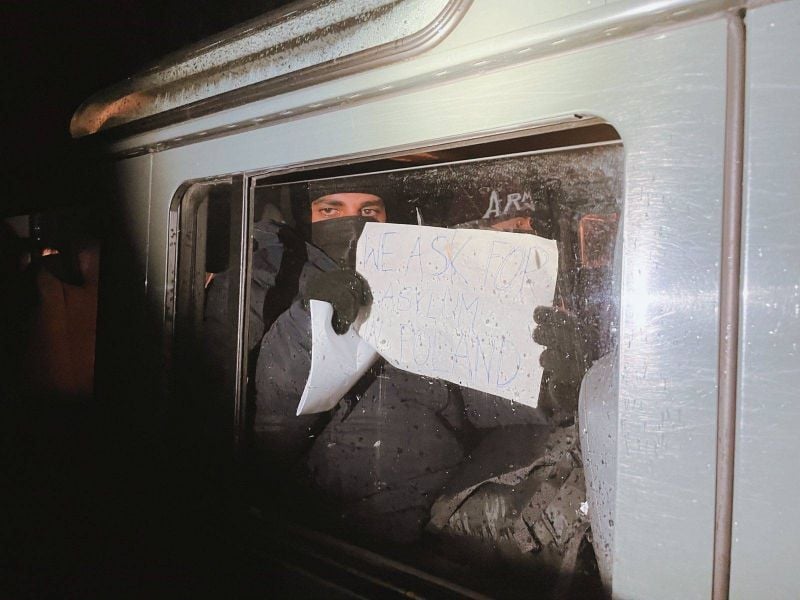

A Syrian asylum seeker in a Polish border guard truck after making a crossing from Belarus. (Credit: Dominika Ozynska, Grupa Granica)

BEIRUT — With the smuggling route across the border from Belarus into the European Union effectively blocked, some of the thousands of would-be asylum seekers who flocked to the eastern European country in recent months have begun to return home.

Hundreds of stranded Iraqis have boarded repatriation flights over the past two weeks after, in many cases, spending weeks stranded in the forested hinterland on the now heavily guarded border between Belarus and Poland. At least 13 people are known to have died at the border to date, according to Human Rights Watch.

But many Syrian refugees who flew from Beirut to Minsk in recent months are in a more precarious situation. Their passports were stamped with a ban on re-entry when they left Lebanon, and with the readily-granted tourist visas that brought them to Belarus now expired and no clear path to asylum either in the EU or in Belarus, they are facing the specter of deportation to Syria.

“I heard that the route was easy, and there are people I know who succeeded,” said Mahmoud, a father of five who sold his land in Syria where he had hoped to one day rebuild his house, left his wife and children in Lebanon and boarded a flight to Minsk in late October, with a hotel reservation and an invitation for a tourist visa in hand. Like other Syrians who spoke to L’Orient Today, he asked that his full name not be published out of security concerns. “Some of them are in the Netherlands, some of them in Germany, some of them in Belgium.”

Since 2015, when he had fled with his family to Lebanon, Mahmoud had never felt secure.

“I’m wanted for army service and my wife is from a known opposition family, so if she returned [to Syria], they would arrest her at the border just from seeing her family name,” he told L’Orient Today, speaking from a house in Minsk that he was sharing with about a dozen other stranded asylum-seekers. “My life would be in danger if I returned.”

Before embarking on the journey to Belarus, he said, “We tried several different routes to travel, through the UN, through the embassies, but there was never any result.”

Since the crisis in Lebanon, an increasing number of Syrians had turned to the sea route to Cyprus, but after hearing stories of Syrians who were pushed back by Cypriot authorities to Lebanon and then deported to Syria, Mahmoud said he didn’t dare to try. He considered going by way of one of the other smuggler routes to Europe, via Libya or Turkey, but those routes also involved a dangerous sea journey. The Belarus route seemed safer.

Like many Syrians who left Lebanon under similar circumstances, his passport was stamped with a re-entry ban when he left the Beirut airport. Many refugees had allowed their Lebanese residency permits to lapse because of the cost to renew them. In Mahmoud’s case, he said, his residency permit had been revoked by General Security shortly before he left Lebanon over procedural issues.

But Mahmoud was not planning to return to Lebanon in any case, and in the beginning, his luck seemed good. Unlike others, who got stuck for days in the airport in Minsk waiting in line to get their visas, he was quickly in and out and arrived at the hotel where a group of friends were waiting for him to make the trip to the border.

That was the end of his good fortune.

By the time they arrived, the previously sleepy border between Poland and Belarus had become a heavily militarized zone, where hundreds of asylum seekers were stuck in the woods between the two countries, in many cases without food or water and in sub-freezing temperatures, being ping-ponged back and forth between Belarusian and Polish border guards for weeks on end.

“We entered Poland several times and the Polish border guards caught us and returned us,” Mahmoud said. “We entered Lithuania and the Lithuanian border guards also caught us and returned us to Belarus. We tried six times.”

At last, disheartened, he made his way back to Minsk, where he found many other Syrians in the same situation.

Mahmoud sent a screenshot of an online poll on a social media group for Syrians in Belarus, to which some 470 people had responded, with about one-third of them saying they could not return to where they had come from because they had been banned from re entry.

Mohamed, another Syrian who had been living in Lebanon since 2012 before traveling to Belarus, told L’Orient Today that he had come in mid-November with four other young men, each of them paying about $4,000 for the trip.

A few days after their journey, Lebanese officials on Nov. 17 ordered airlines not to allow any non-Belarusian citizens to board flights to Belarus unless they were holders of residency there. Lebanon’s Tourism Ministry subsequently issued a circular warning travel agencies not to advertise Belarus as a destination.

“There are people who sold their clothes and the furniture from their houses, there are people who sold their wives’ gold, there are people who sold their houses,” Mohamed said. “We left our families in Lebanon and came. We were expecting we would get to a better situation.”

Instead, they found themselves “stuck in the forest for a week without food or water or anything -- we were drinking swamp water,” he said.

He added that some of the group had been beaten by Belarusian security forces, sending a series of photographs of a man’s badly bruised legs to make his point. Other Syrians who spoke to L’Orient Today said they had been roughed up by Polish and Lithuanian border guards as well as Belarusian forces.

Now, Mohamed and his friends are hiding out in a rented house in Brest, a town near the Belarus-Poland border, afraid to go out in public lest they be caught by Belarusian police with expired visas, Mohamed said. All of the men are banned from returning to Lebanon.

“If we go back to Lebanon they will forcibly deport us to Syria and if we go to Syria the regime will take us to the army, to the war,” he said. “We don’t want to go and die in Syria. We left Syria to escape the war.”

Mahmoud said that some Syrians in Minsk had attempted to contact the UN refugee agency to apply for refugee status in Belarus after their route to the European Union was blocked, but that they were told they must first apply via a Belarusian immigration center. Upon going to the immigration center, he said, they were told they could not apply for asylum.

The media office of the Belarusian foreign ministry did not respond to a request for comment; nor did a Lebanese General Security spokesperson.

Lisa Abou Khaled, a spokesperson for UNHCR in Lebanon, said the agency has not so far heard any reports of Syrians being deported from Belarus to Lebanon, but has been “providing advice and support to the [Belarusian] government in order to improve and strengthen the national asylum system and create favourable environment for integration of refugees in Belarus.”

As for refugees who might wish to return to Lebanon but are banned from re-entry, she said, “UNHCR urges Lebanon to ensure that all individuals who wish to re-enter [their] country of former residence and who may have a fear of return to their country of origin are readmitted so that their protection needs can be properly assessed.”

A representative of the European Union did not respond to a request for comment.

Nadine Kheshen, project coordinator for refugee rights and protection at ALEF, a Lebanese human rights NGO that is a member of the Refugee Protection Watch coalition, told L’Orient Today that the worsening situation in Lebanon, along with fears of deportation to Syria and shrinking opportunities for resettlement in European countries had pushed an increasing number of refugees to gamble on migration routes like the one through Belarus.

“People are taking these extremely risky routes, through Cyprus, through Libya, through Turkey and Belarus because the situation here in Lebanon has become so desperate,” she said.

Now, with the route via Belarus blocked, she said, “In many cases, there’s a very high risk that those returning from Belarus to Lebanon could be deported to Syria,” where reports by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and others have documented that returnees “are being detained, potentially tortured and even disappeared.”

So, she said, “We continue to call on European states to increase their responsibility sharing, increase protection spaces for refugees in Lebanon and neighboring refugee-hosting countries and most importantly to increase opportunities for resettlement or other avenues for residency in other countries.”

In the meantime, even the stories of deaths and harsh conditions on the Belarusian borders have not dissuaded some people from attempting the trip.

A refugee in Akkar who spoke to L’Orient Today said that since those without residency are now banned from flying to Belarus from Lebanon, a smuggler had offered, for an additional fee, to get him a residency permit that would allow him to make the journey. He and the others planning to travel with him had agreed to pay a total of $8,000 each to get to Belarus and then to Germany, of which he had already paid the first $4,500.

Despite reports of the dire situation on the borders and despite the fact that his residency in Lebanon has expired, meaning he will be banned from re-entry, he said he plans to make the trip.

“Before, the situation was better than now,” he said. “After we paid the first part of the money, then we got news that there is danger and robberies and so forth. But now we’re waiting for the residency permits, and if we get them, we’ll go. It’s better than losing the money.”