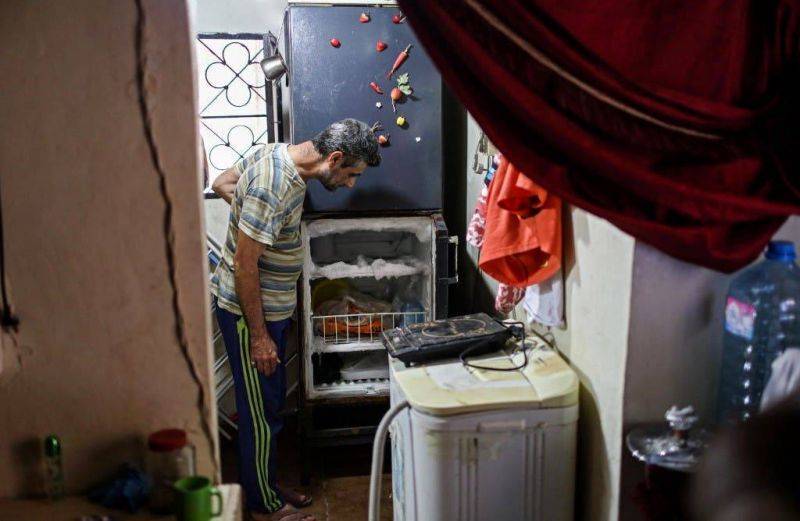

Government inefficiencies have delayed a $246 million World Bank loan meant to finance a program to get cash quickly into the hands of Lebanon's most vulnerable residents, which in theory could have been launched in May or even earlier. (Credit: Anwar Amro/AFP)

BEIRUT — A $246 million World Bank loan approved in January that was originally intended to quickly get cash into the pockets of Lebanon’s most vulnerable residents will not be disbursed until at least August due to a series of administrative blunders on the part of Lebanese officials.

The holdup of the aid program, which in theory could have been launched in May or even earlier, comes as the end of subsidies on essential imports including wheat, medicine and fuel appears imminent, and already struggling families are facing skyrocketing prices for basic necessities as a result.

Among the main reasons for the delays is a slew of changes to the deal that were made by Parliament and ministers without World Bank officials having signed off on them.

When Parliament voted on a draft law for the amended loan agreement in March, caretaker Deputy Prime Minister Zeina Akar assured lawmakers that World Bank officials had already verbally agreed to the changes. According to MP Ibrahim Kanaan (FPM/Metn), the vice chairman of a joint parliamentary committee that had drawn up the changes, Akar had proposed them during a committee meeting in February, a month after cabinet and the World Bank’s board signed off on the original loan agreement.

The changes included reducing the budgets for some administrative and oversight portions of the program by about $21 million to increase the number of families who would receive cash assistance from 147,000 to more than 160,000.

According to the version approved by Parliament, this increase in beneficiaries would also be achieved in part by using donor grants to fund some portions of the program originally meant to be paid for through the loan, including hiring social workers to verify beneficiaries’ eligibility. However, Lebanon has yet to secure the grants.

Ahead of the March vote, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri asked Akar whether the World Bank had agreed to the amendments. Akar replied, “The finance minister will transfer all the remarks to the World Bank, and this is the way we agreed upon, and they will, in their turn, sign it. There is an understanding on this matter.”

The text of the law passed that day by Parliament contradicts itself as to whether the World Bank had already signed off on the amendments. In the same paragraph, the document says the amendments “will be addressed through the minister of finance to the World Bank and will be approved by the World Bank in Lebanon,” but then says that all of the law’s clauses “were approved by the prime minister, the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Ministry of Education and Higher Education, the World Bank and the World Food Program.”

But World Bank officials have since said they did not approve the changes.

Saroj Kumar Jha, the World Bank’s regional director for the Levant area, told L’Orient Today that while government officials had discussed some of the proposed amendments with the bank’s representatives before the parliamentary vote, “it is not accurate to say that what the Parliament has approved was pre-cleared with the bank.”

In a letter sent on May 21 to caretaker Finance Minister Ghazi Wazni, Jha noted that “certain parliamentary amendments can be accommodated without amending the loan agreement. Others, however, will require a restructuring and amendment to the loan agreement.”

Lebanese officials have traded blame over who was responsible for the blunder.

Wazni acknowledged in a televised interview last month that the changes “took place without the agreement of the World Bank” and that the bank had later told the caretaker cabinet to “rectify it.” Despite having signed the amended version passed by Parliament, Wazni said he was “not directly responsible for this.”

Wazni, via a Finance Ministry spokesperson, declined to comment for this article.

Kanaan, who heads Parliament’s Finance and Budget Committee, which was among the committees that drew up the changes, told L’Orient Today that the modifications had come from the cabinet, and particularly Akar.

“The cabinet suggested the changes,” he said. “Zeina Akar said the World Bank agreed with her on the amendments.”

Akar, for her part, told L’Orient Today, “Several meetings were held with the World Bank head and team prior to the last parliamentary session when the draft law was endorsed. The World Bank agreed to all changes raised by all the parliamentarian blocs. And that is why the Parliament went ahead.”

Akar also said that then-caretaker Foreign Affairs Minister Charbel Wehbi had been responsible for the project and that she “just helped when needed.” Wehbi, who has since resigned amid blowback from blaming Gulf states for the rise of the Islamic State and making racist comments on live TV targeting Saudis, could not be reached for comment. Akar later said that Wehbi was “never involved,” citing a potential misunderstanding.

When asked which government officials had been involved in discussions with the World Bank about the proposed changes, Jha said that from the bank’s perspective Wazni was the “authorized signatory on all the loans that we provide to Lebanon, so he’s officially the point person for the bank.” However, he noted that World Bank officials had also met with representatives of the Ministry of Social Affairs, the National Poverty Targeting Program Unit in the prime minister’s office, and Akar as a representative of the prime minister to discuss the program. Asked whether the Foreign Ministry was involved in the talks, a World Bank spokesperson said “not to our knowledge.”

The problematic changes

Among the changes the World Bank cited as potentially problematic was the assumption that some program expenses could be covered by grants rather than the loan funds. According to Jha’s May 21 letter, “There is no confirmation as of today from donor availability.”

Jha told L’Orient Today, “What we had said is we can work with you to find grant money from elsewhere, from other bilateral donors, but we cannot commit to that, because the World Bank doesn’t have any grant making instruments of its own.”

The World Bank’s May 21 letter also questioned reductions in the budgets allocated to developing a database to identify needy households and hiring a third-party monitor, as well as a LL7 million monthly salary cap (currently equivalent to $450 on the parallel market) that Parliament introduced for program staff under the rationale that staff salaries could not exceed those of President Michel Aoun, Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri and caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab.

Another key sticking point was a clause requiring that all program expenses be paid in lira. While the original agreement was for recipients to get aid payments in Lebanese currency at an exchange rate of LL6,240 to the US dollar — which is higher than the official LL1,500 rate and the “bank rate” of LL3,900, but considerably lower than the parallel market rate, which currently exceeds LL15,000 — the World Bank has since insisted that the payouts should be in dollars rather than in the rapidly devaluating local currency.

Jha said that paying beneficiaries in dollars — which would total about $1,500–$1,700 per family per year — would enable the program to increase the number of recipients to about 200,000. This represents 60,000 families more than would be achieved in the version of the loan agreement passed by Parliament. As of Thursday, Jha said that officials including Wazni and Diab had verbally confirmed that the beneficiaries would be paid in dollars.

“They have not confirmed this in writing to us, but as far as we are concerned this is non-negotiable,” he said.

Jha had also said in a post on Twitter on May 24 following a meeting with Wazni that he was “glad to note agreement that ESSN [Emergency Social Safety Net] loan will disburse in USD to eligible beneficiaries.”

However, in a written response to concerns raised by the World Bank that was sent on June 8, Wazni was more circumspect, saying that he would discuss the matter of the currency with the prime minister and “relay to you the final decision about it.”

In part because of the back and forth over the amendments, Lebanon missed a deadline last month to meet all the conditions for the loan to be disbursed. The deadline has been extended to July 28. Jha said that at this point Aug. 1 appears to be the earliest the program could start providing aid.

Apart from the changes made by Parliament, there have been delays in meeting basic procedural requirements for the loan to take effect, including producing a program operations manual and labor management plan, and getting a legal opinion confirming that the agreement complies with local laws.

“In any country, I would expect these things to be done really fast — they should have been done a long time back,” Jha said. “They have not been done yet.”

Perhaps the largest procedural hurdle lies in verifying the eligibility of the families slated to receive the assistance. Lebanon has no centralized database of people in need of social assistance.

According to Jha, “Every time we have a crisis in Lebanon, people tend to start preparing a temporary list of beneficiaries, and as a result we have multiple lists of beneficiaries floating around, which doesn’t really help with proper targeting of people in need of assistance.”

Part of the aim of the $246 million loan was to develop such a centralized social registry. But in the meantime, the Social Affairs Ministry does not have the staff to do the necessary home visits and other procedures to verify the eligibility of all the potential aid recipients.

Assem Abi Ali, who represents the Social Affairs Ministry in negotiations with the World Bank, told L’Orient Today that the ministry is working with the World Food Program to get donor funding, “because we are in drastic need to scale up the number of … people working on the ground in order to verify the biggest number of families as soon as possible.”

Abi Ali said that some 70,000 households, of which 45,000 have already been verified, will receive assistance through other international donors, separate from the World Bank loan program, via the ministry’s existing National Poverty Targeting Program.

The looming end of subsidies

The original idea behind the World Bank loan was to get vulnerable families money to help them weather the economic crisis and offset the increasingly likely removal of import subsidies for essential goods, which are eating through the country’s rapidly dwindling foreign currency reserves.

The World Bank’s vice president for the Middle East and North Africa, Ferid Belhaj, said in a presentation to top Lebanese officials during a visit to Lebanon earlier this month that the implementation delays are “something that both irritates me personally and poses a big question mark for all of us in the international community who would like to help.”

Despite the government’s failure so far to meet the requirements for the initial $246 million, the World Bank has expressed, at least in theory, a willingness to shift even more resources into the loan program.

Jha said the bank would be willing to consider transferring funds from other World Bank programs in Lebanon that were approved but never got off the ground to increase the funding available for the social safety net program. But before that could happen, he said, Lebanon must first meet the requirements to unlock the initial $246 million, and “the cash disbursement to eligible families has to have begun to the World Bank’s satisfaction,” with verified reports from a third-party monitor confirming that the distribution is following the proper procedures.

In the meantime, if the program does not get off the ground quickly, Jha said, “you will see more poverty, more deprivation, more hunger, and this is exactly what this program is [meant] to alleviate.”

Update: Caretaker Deputy Premier Zeina Akar has clarified that former caretaker Foreign Minister Charbel Wehbi was “never involved” in the negotiations over the social safety net program.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that payments to 45,000 already verified households could start once the World Bank gives its go-ahead. In fact, the program providing assistance to those households is funded by other donors, and a portion of the families have already begun receiving assistance.

Clarification: This article has been modified to eliminate a potential misreading of Ibrahim Kanaan’s comments regarding the question of World Bank authorization of the changes to the loan program.