Lebanon’s sprawling kafala industry has endured a year to forget. For decades, the sector had generated value for Lebanese recruitment agencies, their shady foreign associates and — of course — the employers of kafala workers. All that began to change last October, as Lebanon’s economy entered an unprecedented free fall.

Lebanon’s dollar shortage has drained the kafala industry of foreign currency, which is needed to arrange workers’ passage from abroad and pay their wages. In desperation, employers have terminated contracts with maids en masse — notoriously, some even abandoned workers outside their embassies. Non-domestic kafala workers have not been spared: in May, riot police subdued employees of private waste management company Ramco, who were protesting over unpaid wages.

The kafala system has not faced this kind of existential challenge since it first appeared in Lebanon at the tail end of the Civil War. Until the current crisis, Lebanon was attracting thousands of foreign workers every year: in 2019, 32,951 domestic workers entered the country, including 14,070 Ethiopians, 7,407 Ghanaians and 3,824 Filipinos.

2020, kafala’s annus horribilis, could provide an opening to long-awaited reforms that would bring sponsored workers under Lebanese labor laws and protections. Activists describe this step — which would effectively abolish the kafala system — as the only acceptable long-term solution to an immoral, exploitative and dangerous employment scheme.

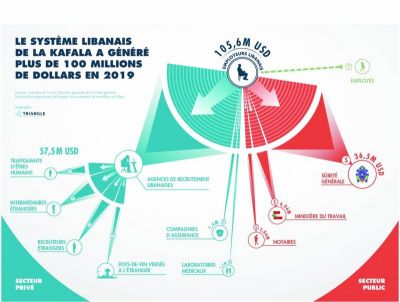

A serious obstacle remains to abolishing kafala: those who profit from leaving the system untouched. In a recent report, we calculated that in 2019, Lebanon’s kafala industry for foreign domestic workers was worth at least $105.6 million. Employers paid an annual total of $57.5 million to Lebanese recruitment agencies, who coordinate foreign workers’ hiring and travel to Lebanon. The agency retains its own profit, while the remaining funds trickle down to overseas recruiters, their sub-agents or brokers, and in some cases corrupt airport officials. This system puts most — if not all — domestic workers at risk of human trafficking and forced labor, according to a recent report.

Employers disburse the remaining $48.1 million after the foreign worker arrives on Lebanese shores. Multimillion dollar cuts go to Lebanese government agencies; General Security received $36.5 million for issuing or renewing residency permits last year, while the Ministry of Labor pocketed $6.06 million in work permit fees (including renewals). Smaller shares are doled out to public notaries ($2.86 million), insurance firms ($1.6 million) and medical laboratories ($1.1 million) — each of which performs services for kafala workers that are required by law.

Of course, employers themselves reap huge rewards from the kafala system. After making these upfront payments, they receive workers ripe for exploitation. By law, kafala workers enjoy fewer industrial protections than Lebanese citizens. In practice, employers can flagrantly abuse those meager rights, thanks to lax enforcement practices. This system rewards employers with a labor force that works longer hours for lower pay.

Commercial interests have already rallied to defend the current kafala system. In October, the Syndicate of the Owners of the Workers Recruitment Agencies in Lebanon (SORAL) successfully appealed against proposed reforms to the standard unified contract for kafala workers. These changes would have slightly increased the rights of kafala workers by law, allowing them to change employers and earn salaries closer to the national minimum wage, which is currently LL650,000. The reforms did not meaningfully address enforcement of these rights, which has always been the primary tool of kafala’s exploitation.

Even these moderate changes proved too much for kafala's powerbrokers to bear. SORAL successfully argued before the Shura Council that, if amended, the unified standard contract would contravene existing labor laws. In truth, the reforms would have diluted the commercial value of kafala workers to employers, undermining the selling point of the industry’s central “product”: cheap and vulnerable labor. SORAL's courtroom victory represented yet another triumph for the powerful business lobby of recruitment agencies.

Meaningful kafala reforms need strong political backing to quash this stubborn opposition, which will continue defending a thoroughly retrograde — but lucrative — industry. Encouragingly, more and more Lebanese are joining calls for foreign workers to receive fair treatment under local laws. This public pressure can drive politicians to resume reform campaigns, like this year's attempted contractual amendments.

By the same token, everyone in Lebanon might reflect on their own implication in kafala’s dirty business. Every day, Lebanese society benefits from the harsh treatment of foreign workers, not all of whom clean up after wealthy families. Kafala workers also man the gas station pumps, toil on construction sites and stack the supermarket shelves that keep Lebanon’s economy stumbling on. The time has come for these workers to receive fair compensation and entitlements for their toil and trouble.

Such is the moral case for opposing kafala. Separately, Lebanon’s financial disaster has delivered a reality check to a country that has been living beyond its means. Now that the artificially inflated Lebanese lira has collapsed, many businesses and families simply cannot afford to splurge on foreign workers. The age of entitlement is over.

There will always be some demand for foreign workers. These employees can continue to provide valuable services, in exchange for fair remuneration and decent working conditions. But business lobbies supporting the status quo will not go down without a fight. Now Lebanon must choose between a more equitable future, and a continuation of the disgraceful current system.

David Wood and Jacob Boswall are journalists and researchers at Lebanese think tank Triangle. Their latest publication is “Cleaning Up: The Shady Industries that Exploit Lebanon’s Kafala Workers.”