Refugee children in a yoga class run by the NGO Koun. (Courtesy of Sandy Boutros)

BEIRUT — Tucked away from the city’s dizzying tumult, on the third floor of a residential building in gentrified Gemmayze, lies the bygone memory of the Beirut Sivananda center. As if heedless of time, the walls of the center once echoed chants and its floors supported innumerable classes.

The Beirut Sivananda Yoga center has the distinction of being Lebanon’s first yoga studio. Its doors opened in 2000 and closed for good during the 2020 COVID pandemic. The first haven for the city’s (then few) yoga lovers, the center did much to sow the seeds of the practice in this country. It was crucial to nurturing a yoga scene that has grown exponentially over the past few years.

Yoga has noticeably gained traction in Lebanon, growing in popularity despite the countless crises gripping the country. Although relatively novel to Lebanese society, yoga is hardly new. The ancient discipline, with roots dating back 5,000 years, has traveled via the currents of globalization to reach Lebanon and the rest of the world. Today it is readily accessible, but this has not been the case for long, especially in the Middle East.

Nabil Najjar, the founder of Beirut Sivananda center, recalled moving back to the country in 1996, after having lived in New York City for fourteen years.

“Even in NYC, at the time [mid-90s] there were not many yoga places,” said Najjar. “Now there is a yoga place at every corner.”

Najjar took up yoga while living in New York, at the recommendation of his sister, who was terminally ill and used the practice to ease her pain.

Upon returning to Lebanon, Najjar’s friends encouraged him to open a yoga studio in Beirut. At the time, he felt like they may as well have asked him to “go to the moon,” he remembered.

Soon enough he answered the call and opened the Beirut Sivananda Yoga center in a Gemmayze flat.

Beirut Sivananda center founder Nabil Najjar in the midst of his routine. (Courtesy of Nabil Najjar)

Beirut Sivananda center founder Nabil Najjar in the midst of his routine. (Courtesy of Nabil Najjar)

Sivananda’s offspring

Mira Siblini taught at the Sivananda center for six years before opening Shiva-Lila Yoga, Beirut’s second yoga studio, in 2010.

Siblini discovered yoga in childhood through her father, a “disciplined army general,” now 85, who learned about the practice after finding a book about yoga in a bunker during wartime.

“It was not popular at all back then,” Siblini said. She recalls that when she went to India for teacher training in 2003, “they were so shocked” to see her, “an Arab woman from the Middle East,” at the ashram.

It has been a part of her life for as long as she can remember. Siblini was a political science graduate and worked at the Lebanese Parliament. After a painful divorce, she decided to fully direct her life toward yoga.

Aaed Ghanem recalls practicing yoga as a university student in Beirut, at the Sivananda center, “the only place in Beirut at the time,” which he later managed for a couple of years. This was before Ghanem opened his own space, the Beirut Yoga Center, which currently operates two branches and offers everything from classic Hatha to contemporary styles like aerial and hot yoga.

Maria Malek, who now runs Humm, a cozy studio off Mar Mikhael street, also got her start in teaching at the Sivananda center. Like Siblini, Malek started yoga at a young age. “My mother used to teach yoga. At that time they didn’t have yoga studios. Teachers used to teach in [people’s] homes. This was in the late ’70s and ’80s, so classes were held at homes, and in fitness centers. I told her to open a studio but she didn’t because there was so much political unrest. It wasn’t a stable environment to open anything. Then she passed away, and I kept it in mind.”

“I wanted to open something closer to [yoga] tradition,” Malek said, “because this is how I was brought up.”

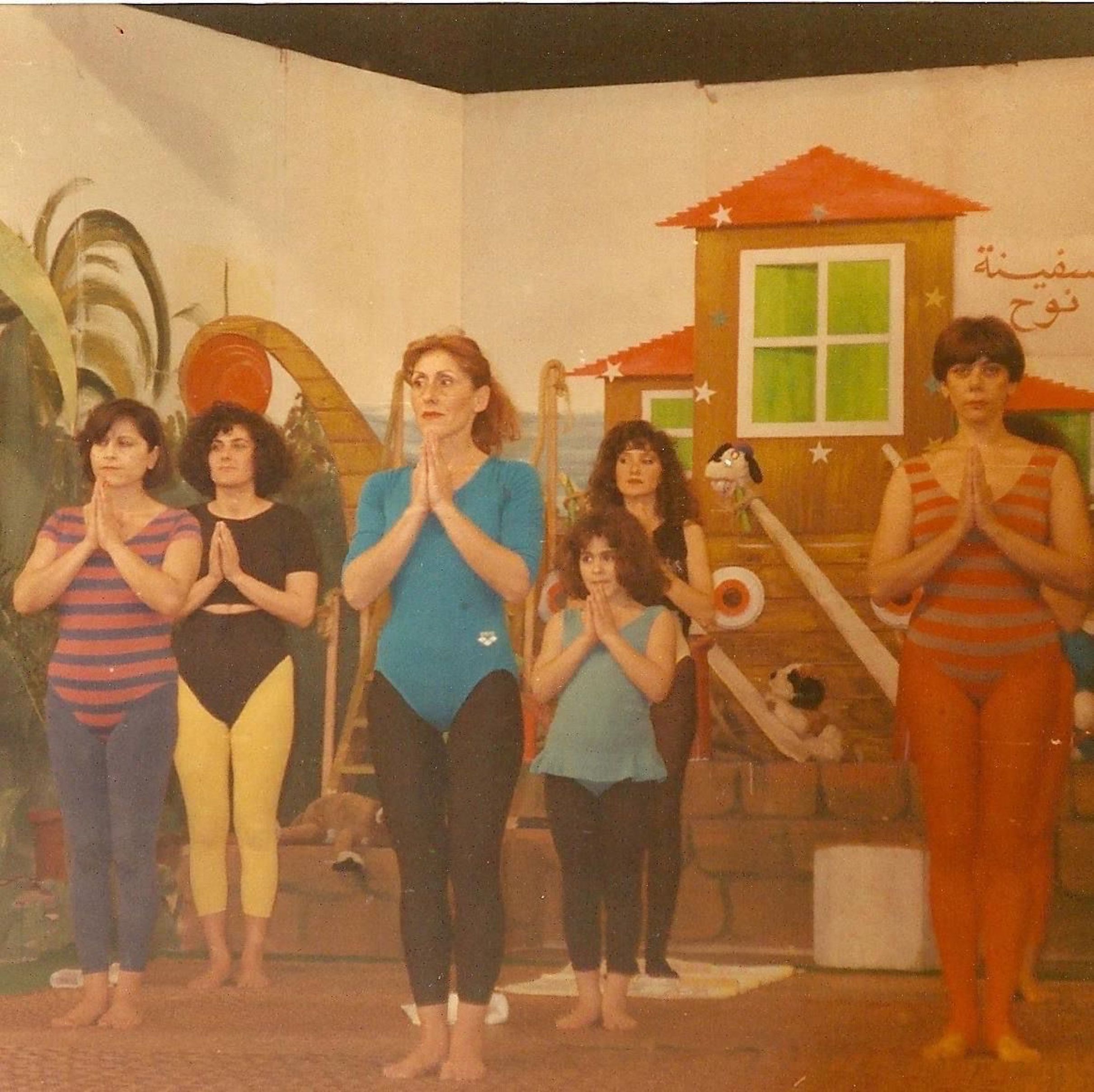

A young Maria Malek and her mother (both in blue leotards) practice yoga on a TV show in the 1980s. (Courtesy of Maria Malek)

A young Maria Malek and her mother (both in blue leotards) practice yoga on a TV show in the 1980s. (Courtesy of Maria Malek)

Lebanese problems

Despite Lebanon’s relative receptivity, yoga has often been misinterpreted by the country’s religious clerics. Nearly every first-generation teacher has a story to tell about this.

When Najjar first opened the Sivananda center, he didn’t do much in terms of advertising, placing only a small plaque on the door. “At that time there were clerics, on both sides, saying that yoga is ‘of the devil.’”

Ghanem recalls being invited to accompany a friend to an interview about yoga on Telelumiere, which he said turned out to be “a trap.”

“I was in a nun’s school. They used to be very harsh with me. They were like, ‘Yoga is a non-Christian practice.’ A lot of people used to think this,” recalled Malek, adding she felt that, “now people are more open," since the practice has become more available. "It’s more popular because it’s 'hip and cool.' This makes it even open more to all kinds of people.”

Sandy Boutros, the founder of Koun, an NGO making yoga accessible to Lebanon’s marginalized communities, was an organizer of the Beirut Yoga Festival, which ran 2014-2017. She recalled the time her grandmother forwarded a text message from a church group.

“In the message, they were asking people to pray for it to rain on Sept. 16 [the date of the festival] so the festival doesn’t happen,” Boutros recalled. “This was 2017.”

Local responses to yoga are not always negative.

“Go back to history. It’s one of the six philosophical eras of India,” Ghanem explained. “In India, Hindus. Buddhists, Sikhs, Muslims and Christians all practice yoga. It’s in the culture. ‘Yoga chitta vrtitti nirodha’: ‘yoga is the calming of the fluctuations of the mind.’ It’s purely philosophical.”

“With Koun I never faced this [backlash] and we work with some pretty religious communities,” said Boutros. “We keep it simple. We speak their language.”

Carla Moukarzel helped found the Lebanon syndicate of yoga teachers, which is registered at the Lebanese Ministry of Labor and offers yoga classes in several universities and schools. For 10 years Moukarzel has taught a three-credit yoga course at the University of Saint Joseph.

Siblini recalls the time one of her students, “a devout Muslim,” told her that she “became a better Muslim because of yoga.”

“When you go to the ashram it’s written on the wall, ‘If you’re a Christian you’ll become a better Christian. If you’re a Jew you become a better Jew’ and so forth,” Siblini said,

“because yoga brings acceptance and works on cultivating non-judgment.”

If anything, Lebanon was more receptive to yoga than other countries in the Middle East.

Hala Okeili, left her career as a lawyer in KSA to open Sarvam Yoga in Gemmayze in 2016.

Recalling that she “went to yoga to heal back pain, but stayed for the mental benefits,” Okeili told L’Orient Today that “in 2012 in Jeddah, there was no yoga. It was not legal in KSA.” Neither was it available online as it is today, she added.

Okeili, who recently opened a second branch of Sarvam in Naccache, remembered when their advertising focused on explaining what yoga is. “We don’t do that anymore because people know what yoga is,” she said, recalling Sarvam’s early days.

Nataly Nasser quit her nursing career after the 2020 Beirut blast and started My Yoga Essentials, a business supplying yoga products, with her husband Marc.

“There was a growing demand for yoga products and we saw this from our sales. Thirty to forty percent of our sales are to newcomers,” she told L’Orient Today. “This tells us people are still coming to the industry.”

108 sun salutations, a June, 2016, event at Martyrs' Square, Beirut. (Photo courtesy of Mira SIblini)

108 sun salutations, a June, 2016, event at Martyrs' Square, Beirut. (Photo courtesy of Mira SIblini)

21st-century Packaging

Despite humble origins rooted in asceticism, yoga has become a global multibillion-dollar industry, which carries a dose of irony.

An average class in Beirut today costs $10 — far beyond the means of most Lebanese living on the margins.

Like all sectors of the “health and wellness industry,” yoga operates as a business and is packaged as such. Aside from the many free online resources, there are initiatives in Lebanon working to make the benefits of yoga accessible to all.

Among them is Boutros’ Koun.

“It's like this [inaccessible] not just in Lebanon but all over the world,” says Boutros, “At the end of the day, even teachers have to pay a lot for their studies.

“Even therapy is expensive. Everything in life is, and yoga is one of them,” she adds. “The best thing about yoga is that once you learn, it stays with you for a lifetime. You don’t need a facilitator for a long period. You can integrate it into your life.”

“Yoga is really popular today in Lebanon, but this doesn’t come without challenges,” Okeili recalled. The challenges, she explained, are like those facing businesses in Lebanon. “There have been a lot of ups and downs with lockdown, losing all the money in the bank in Lebanon. We had to reinvest, rebuilding our space that got completely destroyed after the explosion.”

Ghanem had to close the Beirut Yoga Center branch he opened in Hazmieh days after the 2019 COVID lockdown.

An aerial yoga class at the Beirut Yoga Center. (Courtesy of Aaed Ghanem)

An aerial yoga class at the Beirut Yoga Center. (Courtesy of Aaed Ghanem)

Healing

In its many forms and variations, yoga is an effective tool to pacify the tidal waves of anxiety and unease that arise in times of crisis.

“Everybody comes to yoga for a different reason and no matter what it is, it’s always a good reason,” said Siblini. “Some people come with injuries and you tell them, yes, it’s good for you. Some people come with depression, you tell them yes it’s good for you.

Some people have a lot of stress. You tell them, yes it helps.”

Perhaps yoga has gained popularity in recent years because it is meeting the need for relief.

“When you live in this region where there is financial crisis and political unrest, you’re always worried about what will happen tomorrow,” said Malek. “Where will I be next month? Will I have savings? Will it be worse? Will it be better? So being in the present moment actually helps you to reduce that anxiety.”

Siblini echoed this sentiment. “After the crisis in Lebanon and the explosion, we’re all out of balance,” she reflected.”One of the main benefits is that [yoga] helps restore that inner balance.”

Today, the walls that once enclosed the Sivananda center reverberate the chatter that spills from Gemmayze’s sidewalk pubs and cafes, along with the language lessons of the Levantine Institute, which now occupies its place.

Najjar will not reopen his center.

“I think I’m done with that part of my life,” he said. “There are others that are very competent and teaching, running yoga centers. It’s their turn.”