Entrance of the Byblos exhibit in Leiden on Jan 15, 2022. (Credit: Farah-Silvana Kanaan/ L'Orient Today)

Meandering through a maze of carefully constructed pop-ups, accentuated with purple — a color the Phoenicians are said to have invented — it’s as if a long lost piece of home had mysteriously turned up in the Netherlands.

Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port, hosted by Leiden’s National Archaeological Museum of Antiquities, boasts over 8,500 years of pre-Lebanese history. Not only is it the largest exhibition about ancient Byblos to date, but it’s also the most global, assembling an astounding 500 objects from the National Museum of Beirut, the museum of the American University of Beirut (AUB) augmented by loans from such international institutions, such as the Louvre, the British Museum, Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, and Brussels’ Royal Museums of Art and History.

Continuously inhabited from the Neolithic era, when it was a sleepy fishing village, to the present, the coastal town a few kilometers north of Phoenician Berytus has witnessed a veritable parade of civilizations come and go. The hoard of objects on show is, with its accompanying audio-tour, fascinating and astoundingly intact but the show’s organizers have gone one better, creating an immersive experience for visitors. As we learn more about what moved goddesses and kings, fortune-seekers and fishermen, whose stories are part of Byblos’ long history, myth and reality are interwoven.

Ancient Byblos’ archaeological site. (Courtesy National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden)

Ancient Byblos’ archaeological site. (Courtesy National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden)

These stories come alive through exciting drawings sprinkled throughout the exhibition on colorful panels by renowned designer Karst-Janneke Rogaar, who drew inspiration from the archives of the Netherlands Institute for the Near East (NINO). The mise-en-scene, designed by Anika Ohlerich and Kathrin Hero from Archetypisch Spatial Design, is made all the more spectacular by its 3D reconstruction of the port city, accompanied by drone-shot photos of the ruins and the dreamy landscapes adjacent Byblos, supplemented by visuals of the initial excavations of the site at the beginning of the 20th century.

There is even an olfactory element to the show, as the lingering scent of cedar follows you wherever you go.

Life’s essentials

The collection of artifacts is almost overwhelming. People stand in line to study the intricate details of the statuettes, jars, tablets, weapons and a wealth of precious jewelry so stylish you want to try it on.

A collection of tiny faience (tin-glazed) figurines, the largest found outside Egypt, from Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port. (Credit: Farah-Silvana Kanaan/L'Orient Today)

A collection of tiny faience (tin-glazed) figurines, the largest found outside Egypt, from Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port. (Credit: Farah-Silvana Kanaan/L'Orient Today)

Some of the pieces on show are adorable. A collection of tiny faience (tin-glazed) figurines, the largest found outside Egypt, includes hedgehogs, baboons, hippopotamuses and deformed human figures. It conjures up images of little kids playing with them, acting out a fantasy world.

Other exhibits are hilarious, demystifying our forefathers by illustrating their pedestrian lives. A limestone couple bearing the Levantine names Terer and Irbura are shown hanging out together circa 1350 BC. The description depicts Terer as a “stereotypical man of the Levant.” As someone from the Levant, you can’t help but be excited at the prospect of learning what wildly interesting daily adventures our forefathers encountered. Edging closer to the protective glass, the answer doesn’t disappoint: Terer is drinking beer through a straw as his spear leans against the wall. Irbura sits, looking rather bored.

Some things never change. All that’s missing is a tiny bowl of termos (Lupini beans).

Golden weapons from the Obelisk temple 2000-1600BC displayed at the Byblos exhibit in Leiden. From: Lebanese Ministry of Culture/Directorate General of Antiquities. (Credit: Farah-Silvana Kanaan/L'Orient Today)

Golden weapons from the Obelisk temple 2000-1600BC displayed at the Byblos exhibit in Leiden. From: Lebanese Ministry of Culture/Directorate General of Antiquities. (Credit: Farah-Silvana Kanaan/L'Orient Today)

Another amusing description accompanies a golden dagger, unusually found with its matching scabbard, which shows “animals being brought to man,” perhaps en route to being consumed. “Donkeys were characteristically associated with males of the elite in this period,” it reads, “although it is not clear why.”

One touching artifact captures how life thousands of years ago still echoes today. A mosaic depicting life in a Roman-era Byblos household, dating from around 100-300 AD, combines “the three qualities that are essential to life: Eros (love), Acme (quality), and Charis (grace, beauty.)” It’s a handy reminder, even in 2023.

Other exhibits resonate with contemporary themes as well, though the details are more exotic. A clay artifact found in Sippar, Iraq, dating from around 523-468 BC lists the taxes collected by a certain Rikis-kalamu-Bel, governor of Byblos during the reign of Archaemenid King Darius. The tax payments — “reddish-purple and bluish-purple wool, two jars of wine and cedarwood” — reads like a list of must-haves for a cold winter night by the sea, or in the mountains.

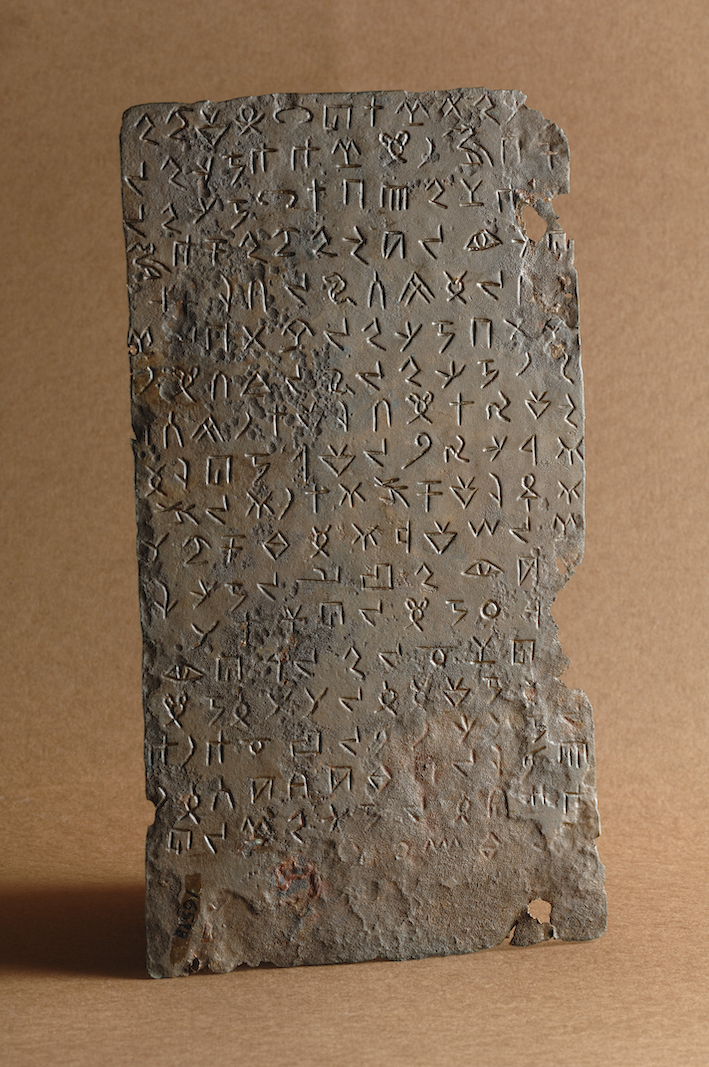

A plaque bearing pseudo hieroglyphs, from Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port. (Courtesy National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden)

A plaque bearing pseudo hieroglyphs, from Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port. (Courtesy National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden)

The Leiden exhibition documents one of Byblos’ periods of decline with one of the Amarna letters. Written on clay tablets, dated 1360s-1330s BC, the correspondence documents the struggles of King Rib-Hadda at a time when his city was no longer the most important port on the eastern Mediterranean coast.

In Amarna letter no. 114, he writes that pirates have seized one of his ships, farmers are fleeing their land, and soldiers have abandoned their posts. He blames all of these misfortunes on the Egyptian pharaoh, Byblos’ suzerain.

It isn’t hard to find a parallel with contemporary Lebanon — a country ruled like a pirate enclave, whose soldiers are making so little money that many don’t show up for work, whose common folk are desperate to flee.

A cross section of a cedar log, from Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port. (Courtesy National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden)

A cross section of a cedar log, from Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port. (Courtesy National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden)

Pharaonic Egypt became the suzerain of city states like Byblos around 3200 BC. Cedar trees — which blanketed the hills above the city — soon became one of the city’s most prestigious exports. Cedarwood timber was used to construct temples and royal tombs, and in later periods also for the boats that ferried the deceased to the realm of the dead. The Byblos exhibition includes a single cedar medallion, a cross section of a log whose exposed rings recount the silent tale of the tree’s life.

These artifacts are impressive, even after repeat viewings. Seeing them together – with their different civilizations, cultures, languages – it’s impossible not to feel some pride, though it seems Lebanon’s multicultural history is more intact than its multicultural society today.

Given the current collapse of the country that inherited Byblos, it is refreshing to be reminded that the city, this patch of the eastern Mediterranean coast generally, was once a cradle of civilizations, an ancient force to reckon with, even a light in the darkness.

"Byblos — The World’s Oldest Port" is up through 12 March.