A still from Manon Nammour’s 2019 short Barakat. Nammour’s debut feature film project "Don't Worry I'm Not OK," currently under development with producer Nicolas Khabbaz, won the 5,000-euro Creative Entrepreneurship Award during ESA/Fondation Liban Cinema’s inaugural Creative Entrepreneurship Producers Training Course. (Credit: Pauline Maroun, courtesy of Manon Nammour)

BEIRUT — Lebanon’s filmmakers work in a uniquely hostile environment. Through its distinguished and eccentric film history, the country has nourished widely respected filmmaking artists and technicians. A film industry, however, never took root in Lebanon’s small, merchant-dominated economy.

Nowadays hostilities are particularly fierce. To help ameliorate some of the challenges confronting the country’s film sector, Fondation Liban Cinema (FLC) president Maya de Freige last week unveiled a Lebanese film fund, the first in the country’s history, founded in collaboration with the European Union.

FLC board member and freelance producer Myriam Sassine has been deeply involved in this project. A prolific producer with Abbout Productions, Sassine has shepherded well over a dozen feature films to market, several since the collapse that accelerated in late 2019. She speaks to L’Orient Today from Greece, where she’s attending the Thessaloniki International Film Festival, serving on the jury of TIFF’s Agora Crossroads Co-production Forum.

“Maya de Freige has been actively trying to get a Lebanese film fund for many years,” Sassine says. “After the crisis started, we went to several entities, among them the EU, and presented a project in two parts. One is a producers’ training course, the other a Lebanese Film Fund. The EU agreed to fund both parts of the project for one year.

“The grant for the entire project is 150,000 euros with 75,000 euros going to the fund. It’s a small envelope,” she acknowledges, “but for us it was a good start. Hopefully next year there will be funding from the EU or from another source.”

Sassine focussed her energies on the training project — the Creative Entrepreneurship Producers Training Course.

“As a producer I wanted to be able to apply myself one day,” she laughs. “So I worked on the broad strategy. Not the details.”

Financing: Anyplace but here

Cinema, as the adage goes, is a greedy art. While plenty of great work has emerged from small film crews on minute budgets, the collaborative nature of film — from financing to production to distribution — devours capital in a way that other forms, an online poetry magazine say, do not.

In lieu of swaggering US-style production companies, able to bankroll movies on an industrial scale, film producers worldwide have had to be innovative to fuel their work. The most obvious source, investors (aka “private equity”), can be unreliable. In a climate of economic instability (like the current one), financiers are leery of committing resources to projects without a guaranteed return — “guaranteed return” itself being at odds with creative freedom.

Lebanon’s economy is not renowned as a model of stability. As a number of this country’s contemporary film producers might quietly attest, its investors are particularly averse to risk, preferring to gamble on safer havens — like government debt.

Lebanon’s film producers have thus sought funding outside.

The Lebanese state has historically been uninterested in supporting cultural production — FLC is a non-state body — but states that value and support the work of their artists have created funding institutions. Fortunately for Lebanese filmmakers, the largesse sometimes seeps through national borders. Europe, particularly France, has played a significant role in facilitating film production in the MENA region, notably in the late-twentieth century, both through direct financing and international co-productions.

Europe’s role in regional film production has declined this century, while many of the Arab world’s legacy film funds, like Syria’s, had already waned. International cultural institutions like Culture Resource and the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture have stepped into this vacuum. Meanwhile ambitious state-based co-production markets and funds — notably those associated with the now-expired Dubai and Abu Dhabi film festivals — have come and gone.

In Egypt, the Cairo film festival’s co-production market persists, while the 2022 edition of El Gouna film festival, and its film production platforms, were postponed until 2023. The Doha Film Institute’s cinema incubator remains a major regional player. More recently, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has sponsored an aggressive regional film-development platform to accompany Jeddah’s Red Sea Film Festival.

This is the regional film financing landscape which Beirut’s fledgling fund has entered.

Lebanon’s film fund

The Beirut fund’s first call for applications has been issued with a very short deadline — the end of November — with the results to be announced in January. Sassine says this is in tune with the fund’s original strategy, namely to target projects well into production and in post-production.

“We wanted to help films that are somehow stuck — whether in post-production or in need of a small boost to start shooting — to get money and quickly,” she says. “Because it’s a smaller envelope of assistance, we wanted it to be as helpful as possible.”

Funding applications will be reviewed by an independent jury of film professionals whose members — three Lebanese, a Tunisian, and a Jordanian, their names withheld to protect the innocent — will decide how to fairly distribute the 75,000 euros among four-to-six feature film projects. The minimum grant is expected to be 5,000 euros, the maximum 20,000 euros.

A fund’s criteria are always important. Fund manager Jessica Khoury says the Lebanese Film Fund will favor arthouse production — great news, given that financing for independent cinema has been badly hit by the COVID-wrought global economic slowdown.

“Naturally we will support artistic films more than commercial. It’s about the directors’ talent, how the film is made, whether or not it needs these funds to be made. These will be the main criteria. How much we give to each film will also depend on the stage each film is at and their respective needs.”

Khoury speaks to L’Orient Today from Cairo, where she currently works with Film Clinic production company. She has worked with MC distribution (Metropolis Cinema’s distribution arm) and Abbout Productions. For the past two years she’s also managed Ayyam Beirut al-Cinema’iyya and Beirut Cinema Platform — respectively, the Arab film festival and co-production platform of Beirut DC, the film production association catering to Arabic-language indies.

The Beirut fund will be open to all Lebanese-made feature film projects. In this it departs from the model of funds operating elsewhere in the region, whose incubators target directors’ first and second features — the same profile as that of blue chip exhibitors like Cannes’ Semaine de la Critique.

“Within the region, it’s easier to finance your first and second feature, but once you get to the third film, you struggle to find even small sums of money,” Khoury says. “After your second feature, you must compete with a huge pool of directors, whether for European or local funds.”

Khoury says the Lebanese fund’s juries won’t award financing on the basis of the success of directors’ past films.

“I think directors can do a great film and then the next one will be not so good,” she reflects. “This is not going to be a deal-breaker. Directors don’t need an excellent track record with their films. The films don’t have to go to A-list festivals. The aim is to support these filmmakers at any stage of their career, to make sure that more films are made in Lebanon.”

Conventionally the state would be involved in the creation of a national film fund. Khoury reassures L’Orient Today that Lebanon’s Ministry of Culture is in no way involved in this project.

“The Foundation has been trying for 10 years to create a fund but of course it never led anywhere,” she says. “This fund is financed by the EU. Hopefully someday we will have a fund like those within the region.

“At this stage I’m sure that the government, whenever there is one, will not support a film fund. But I think that if this fund is successful, if this money helps Lebanese filmmakers complete their projects, the fund’s financing will be renewed. I hope. I don’t know if we will have a [Lebanese-financed] fund in the next 10 years, but we must keep working to make it happen.”

Producing entrepreneurial producers

The training course that preceded the fund announcement is designed to help Lebanese film producers cope with an increasingly challenging film financing landscape. Sassine was responsible for supervising the program and led several sessions herself. With Smart ESA director Selim Yasmine, she tutored the five participants in making their pitch to the jury.

“There are not many producers in Lebanon,” Sassine says. “There are many more film projects and producers cannot sustain more than two or three at a time, especially given the Lebanese cinema economy.”

Creative Entrepreneurship for Producers drew upon the expertise of both ESA tutors and several guest mentors, including French producer Gabrielle Dumon, French Sales Agent Hedi Zardi and entertainment lawyer Christel Salem.

“We tried to expand their knowledge of the film market,” Sassine says, “of how sales agents work, how co-production works, how film financing can be accomplished. We did case studies and looked at many financial plans showing different ways of funding films. On the entrepreneurial side, they worked a lot on building your company into one that sustains itself, successful digital marketing, the art of negotiation etc. Lebanese producers don’t have access to this — except in workshops outside Lebanon that aren’t always accessible to everyone.”

Each of the five participating producers — Rosy Hajj, Christelle Younes, Gaby Zarazir, Simon Soueid and Nicolas Khabbaz — pitched feature film projects to a jury of five: filmmaker and artist Joana Hadjithomas, co-director of titles like Memory Box and I Want to See among others; Gabriel Chamoun, CEO of regional production house The Talkies; Sandra Abboud, head of executive education at ESA; entrepreneur Maroun Chammas; and de Freige.

The jury awarded two prizes. The EU bestowed the 5,000-euro Creative Entrepreneurship Award to Nicolas Khabbaz, to help fund the development of Don't Worry I'm Not OK. This is the first feature-length fiction of Manon Nammour, whose shorts have garnered attention and awards at international film festivals.

During jury deliberations a second prize of 5,000 euros, the Maroun Chammas Recognition Award, was added and given to Rosy Hajj for the project A Road to Damascus, by writer-director Meedo Taha. In addition, the Berlin Arist-In-Residency Award (Berlin AIR) was given to Gaby Zarazir to develop the fiction film project Trip to Jerusalem, which the producer will co-direct with his brother Michel Zarazir. Berlin AIR consists of a three-month artist residency in Berlin, funded by Medienboard Berlin Brandenburg.

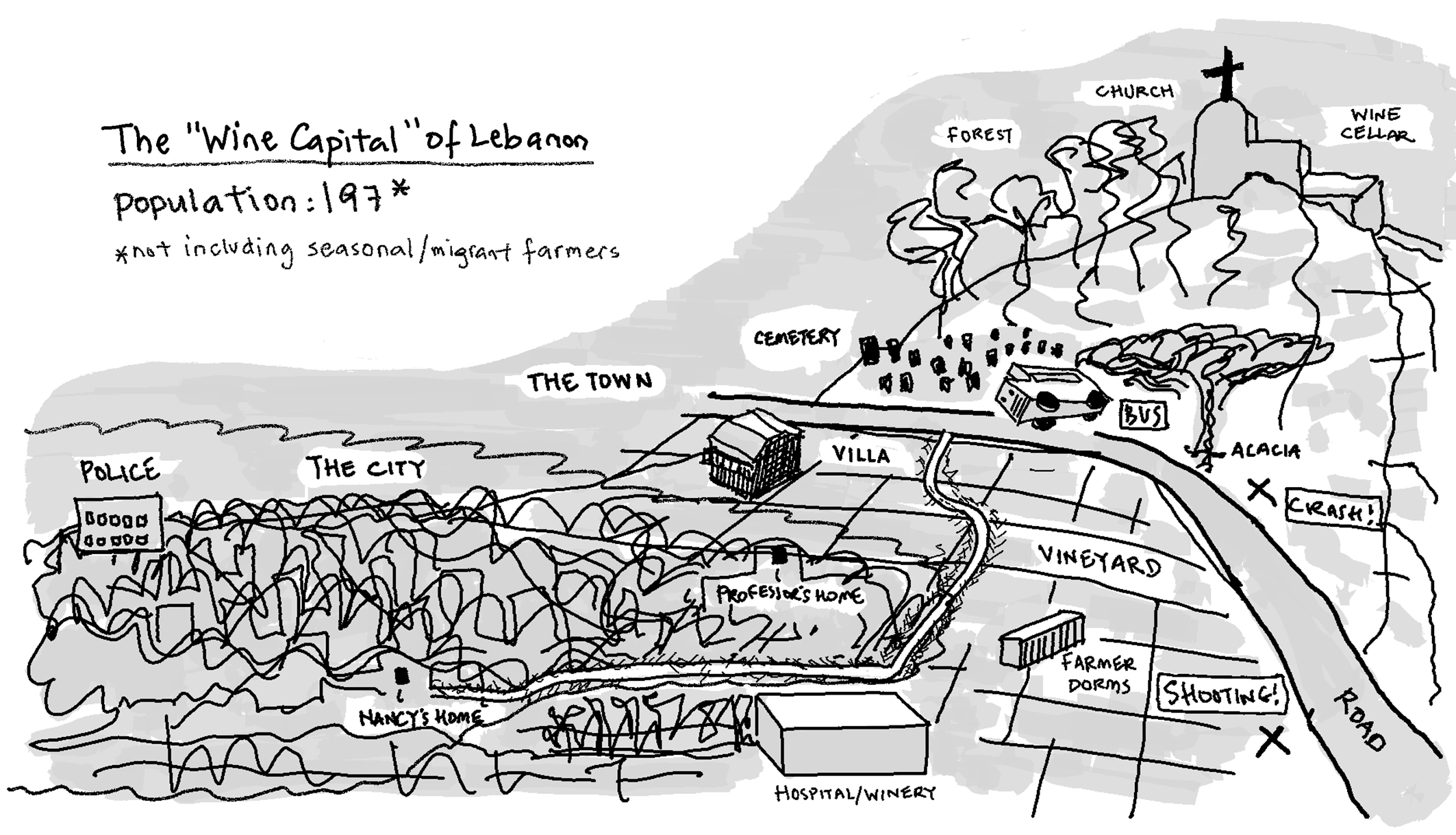

A treatment sketch from "A Road to Damascus," the debut feature film project of writer-director Meedo Taha, currently under development with producer Rosy Hajj, winner of the 5,000-euro Maroun Chammas Recognition prize, awarded during ESA/Fondation Liban Cinema’s inaugural Creative Entrepreneurship Producers Training Course. (Courtesy of Rosy Hajj).

A treatment sketch from "A Road to Damascus," the debut feature film project of writer-director Meedo Taha, currently under development with producer Rosy Hajj, winner of the 5,000-euro Maroun Chammas Recognition prize, awarded during ESA/Fondation Liban Cinema’s inaugural Creative Entrepreneurship Producers Training Course. (Courtesy of Rosy Hajj).

Asked what skill set Lebanese producers need to get challenging, artistic films made and seen in this hostile environment, Sassine is pragmatic and oddly optimistic.

“There’s not one film in Lebanon that was produced the same way as another,” she says. “You have to always look for new opportunities to see who you can convince. You may get rejections from the usual grants and institutions that support Lebanese cinema, but that doesn’t mean that the film should not be made.

“This is where a producer’s work gets tougher, because she needs to find a way that allows the film to be made in a way that doesn’t lower its production values and artistic worth, despite the absence of funds.”

“The good news for young producers is that a lot of work has been done in the last 10 years. They’re not starting from nothing. Lebanese cinema has been evolving and it’s getting recognition worldwide. Some of the films are making a return on investment. So they are not working in virgin landscape, like when I started.

“The challenging part is that sometimes producers rely heavily on grants and these grants are selective and very competitive. So sometimes you don’t get the money and find yourself a bit lost in how you should proceed. I think Lebanese producers today have examples they can be inspired by, but there’s a lot of room for innovation, strategy and creativity in finding the right balance of equity, grants, and co-production for his particular project.”

The participants in what is hoped will be the inaugural edition of ESA/Fondation Liban Cinema’s Creative Entrepreneurship Producers Training Course. (Courtesy Fondation Liban Cinema).

The participants in what is hoped will be the inaugural edition of ESA/Fondation Liban Cinema’s Creative Entrepreneurship Producers Training Course. (Courtesy Fondation Liban Cinema).

Sassine is optimistic that, even now, there are opportunities available for young producers to get challenging projects completed and distributed.

“Lebanon never had public funding, so we always looked everywhere else for money. This didn’t change,” she laughs. “We’re still looking everywhere else for money.”