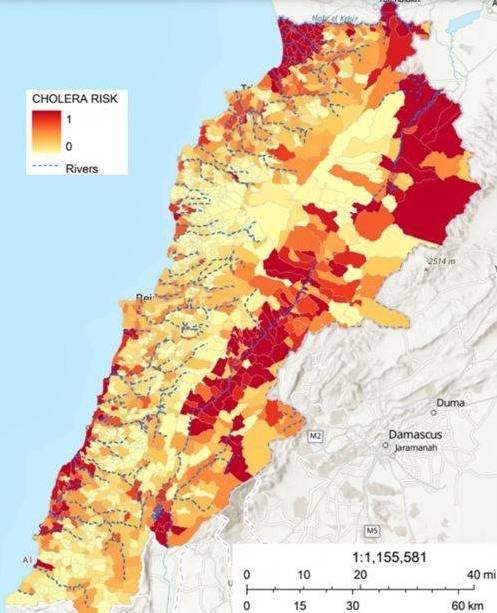

A map provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), marking in red the regions that are most at risk. (Courtesy of the World Health Organization)

BEIRUT — Cholera is making a comeback in a collapsing Lebanon, coupled with the ongoing conflict in neighboring Syria. Approximately 18 cases were already confirmed in the country as of Oct. 10, just days after the first case was detected, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Lebanese Ministry of Health during an interview with L’Orient-Le Jour.

The first 14 cases were detected on Monday, in a refugee settlement in Akkar, near the Lebanese-Syrian border. The other four cases, who were also Syrian refugees, were detected late in the day in Arsal (Baalbeck-Hermel).

Cholera causes acute diarrhea caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with Vibrio cholerae present in feces. But it can also be asymptomatic.

“Cholera transmission is closely linked to inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities. Typical at-risk areas include peri-urban slums, and camps for internally displaced persons or refugees,” according to the WHO.

Minister of Health Firas Abiad during his tour in Akkar on Sunday to inspect the areas already affected by the disease. (Courtesy of Michel Hallak)

Minister of Health Firas Abiad during his tour in Akkar on Sunday to inspect the areas already affected by the disease. (Courtesy of Michel Hallak)

The threat of an epidemic

According to the Ministry of Health, five severely affected people are hospitalized, while eight patients are suffering from mild symptoms and five others are asymptomatic. The death of an infant from acute diarrhea is still under investigation.

While the WHO refuses for the moment to speak of an epidemic in Lebanon, it is because the disease has not yet spread throughout the country. But the threat is there. In less than two months, cholera has claimed 36 lives in Syria, where more than 10,000 people have been infected, according to UN estimates.

With the constant displacement of people between Lebanon and Syria, and the catastrophic sanitary conditions in refugee camps and disadvantaged regions, there is no doubt that the number of contaminations is increasing, because there is not enough money to improve the sanitary infrastructures in the midst of the economic crisis. International aid is becoming scarce.

The ground is therefore fertile for the spread of diseases related to hygiene and sanitation, like hepatitis A elsewhere, which have the same transmission route. Not only is drinking water widely polluted, but is often mixed with wastewater, both in Syrian refugee camps and in lower socioeconomic areas.

The WHO is now sounding the alarm. “Lebanon is at high risk of cholera outbreak,” the organization warns.

Thirty years after the last epidemic in 1993, fears are high that the disease will spread rapidly throughout the country, particularly in areas bordering Syria, in areas without access to clean drinking water, or not connected to sewage systems.

This outbreak could cause “more suffering to a healthcare system that is already impacted by the crisis and COVID-19,” warns Dr. Alissar Rady, head of the technical team at the WHO Beirut.

This is not to mention “the high risk of antibiotic resistance of the bacteria, given that in Lebanon there are no restrictions on the use of antibiotics.”

Neither drinking water nor sanitation

The reasons for these high risks are multiple.

“The infrastructure in the countries of the region [including Lebanon] that are going through socioeconomic and security crises is deteriorating rapidly. At the same time, the capacity of governments to maintain good control over water and sanitation security is weak, especially with the energy crisis,” Rady added.

“The continuous movement of people, who are at high-risk, between countries in the region and those considered endemic,” especially between Lebanon and Syria, needs to be taken into account.

“Added to this is the scarcity and high cost of water, which triggers dependence on unreliable sources or suppliers. Not to mention the lack of funding needed for humanitarian assistance, especially in vulnerable settings,” said the WHO.

“As an example, already in 2016, 51 percent of households in Lebanon were using contaminated water,” the organization notes.

“In the north of the country, officials have told us that 100 percent of the water sources are polluted,” said Dr. Atika Berry, head of the preventive medicine department at the Ministry of Health.

The repercussions are obvious, especially on agricultural products. Dr. Abdel Rahman Bizri, a specialist in infectious diseases and clinical microbiology and an MP for Saida, said the impact is clear.

“The basic infrastructure of public health is not functional in Lebanon, whether it is the quality of drinking water, wastewater or the often-contaminated food,” he said.

As a result, “The number of reported cases could be just the tip of the iceberg,” he added. However, he said he refuses to be alarmist.

“Only 20 percent of confirmed cholera cases have diarrhea. The rest have only mild symptoms or are asymptomatic,” said the specialist.

If left untreated, diarrhea caused by cholera can be accompanied by severe dehydration and even death within hours, according to the WHO.

What state strategy?

“The Ministry of Health, in cooperation with the WHO, has updated the strategy it had prepared in 2016 when 300,000 Lebanese nationals partook in a pilgrimage to Iraq,” explained Berry.

“This strategy is based on three pillars without which no prevention is possible: Raising awareness of sanitary measures among the population, the permanent provision of unpolluted water to all households and finally the safe wastewater treatment and disposal,” Berry said.

It is within this framework that caretaker Education Minister Abbas Halabi called on Monday the educational institutions to take the necessary sanitary measures to prevent a cholera outbreak, including raising awareness among the students.

This is added to “the necessary cooperation between the Lebanese authorities and international organizations,” especially in regards to the refugee communities (Syrian and Palestinian).

It is a cooperation that sometimes becomes obstructing when it comes to improving the sanitary conditions of refugee communities.

“Lebanon needs support to fight the epidemic,” Rady said. “Because the government’s capacity is very limited.”

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour.