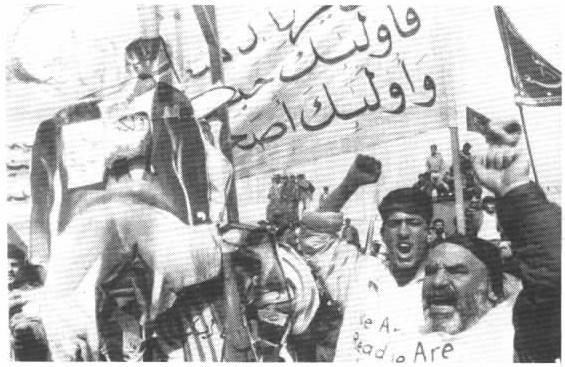

In this file photo taken on Feb. 26, 1989, pro-Iranian Hezbollah burn an effigy of British writer Salman Rushdie. (Credit: Nabil Ismail/AFP)

BEIRUT — In Lebanon, the controversy surrounding the publication of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses played out in the context of the final years of the country’s 1975-90 Civil War in light of Iran's growing presence in the country through its proxies.

The book is banned in Lebanon to this day, while a previous unsuccessful attempt on the writer’s life was made by a Lebanese attacker in 1989, soon after a fatwa (legal opinion) against Rushdie’s life was issued by Iran’s then-Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Lebanon’s Hezbollah was at the time openly supportive of the fatwa, a position that the group has since walked back, at least in public statements.

When it emerged that Hadi Matar, the man who stabbed and wounded Rushdie on Friday at an event in New York, was of Lebanese origin, Hezbollah publicly distanced itself and its patron Iran from the attack.

However, at the time when Khomeini issued his 1989 fatwa, saying it was legitimate for Muslims to kill Rushdie, Hezbollah promised to execute the author.

On Feb. 26, 1989, the party led a protest against Rushdie in support of Khomeini’s fatwa in the southern suburbs of Beirut and in Baalbeck. The Associated Press and L’Orient-Le Jour reports from the time estimated that several thousand attended the march. Many wore banners with inscriptions reading, “We are ready to kill Rushdie.”

At the protest, L’Orient-Le Jour reported the speech of a young Hassan Nasrallah, then 29 and not yet leader of the party, saying: “Rushdie and those who publish his Satanic work will be executed. Britain can hide Rushdie for a few days or a few weeks, but he has no choice: either he must remain in hiding, or he must appear and then he will be executed.”

The demonstrators held up an effigy depicting Rushdie in the shape of the devil, which was subsequently burned at the end of the demonstration, as photographed by Nabil Ismail for Agence France-Presse.

Religious dignitaries at the head of the demonstrators who marched in the southern suburbs in 1989. (Credit: Toufic Abdallah)

Religious dignitaries at the head of the demonstrators who marched in the southern suburbs in 1989. (Credit: Toufic Abdallah)

The first documented case of a Lebanese citizen trying to kill Rushdie was at the Beverly House Hotel in London's Paddington on Aug. 3, 1989. A 21-year-old man, sometimes identified as Mustafa Mazeh and other times as Gharib Mazeh, died when the explosive device he was preparing to use against Rushdie prematurely exploded.

Like Rushdie's other Lebanese attempted-assassin, Matar, who was born in the United States, Mazeh was a Lebanese expatriate, but in his case born in the African nation of Guinea. A 2005 London Times investigation by Anthony Lloyd found that he had joined Hezbollah as a teen while on a visit to his Lebanese hometown and flew to London on a forged French passport.

Although Hezbollah did not claim responsibility for Mazeh’s actions, several reports indicate a link to the party. Quoting a handwritten statement that had been delivered to Beirut’s Annahar newspaper, a Los Angeles Times wire service article from 1989 reported that the party had said, “Muslims mourn their first martyr, Gharib, who died while preparing a daring attack against the apostate Salman Rushdie.”

Additionally, in his 2006 book Distant Relations, Boston University professor Houchang Chehabi claims that a Hezbollah commander who went by the name Abu Chadid confirmed Hezbollah’s involvement in an interview with an Iranian magazine, saying the armed group answered the fatwa’s call through this assassination attempt.

Moreover, in Tehran’s Behesht Zahra cemetery, a symbolic tomb was built to commemorate Mazeh, and bears the inscription “Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh The first martyr to die on a mission to kill Salman Rushdie.” His grave stands next to symbolic tombs of the suicide bombers that killed American Marines in the 1983 Beirut Barraks boming, as well Hezbollah commander Imad Mughniyeh who was assassinated in 2008 in Damascus.

The Satanic Verses fatwa also had an impact on Westerners on the ground in late-Civil War Beirut.

In 1990, relatives of three British hostages kidnapped in Lebanon in the 1980s pleaded with Rushdie and his publisher Penguin to refrain from publishing the paperback edition of his book, fearing that this would exacerbate the situation for their family members.

“We believe the time has come to balance the principle of free speech against that of self restraint, which is also necessary in a civilized society,” the families said in a statement.

Although Hezbollah did not claim responsibility for the kidnappings, which were carried out by groups linked to it, it was widely assumed that Hezbollah was responsible for abducting the UK citizens, along with American journalists and academics working in Lebanon.

The three British hostages were Terry Waite, Brian Keenan and John McCarthy.

“We are ready to kill Rushdie” shout these demonstrators who brandish an effigy of Rushdie resembling a devil and suspended from a gallows. (Credit: OLJ archive photo by Toufic Abdallah)

“We are ready to kill Rushdie” shout these demonstrators who brandish an effigy of Rushdie resembling a devil and suspended from a gallows. (Credit: OLJ archive photo by Toufic Abdallah)

At that point Rushdie had received death threats attributed to the Iranian fatwa and was living in hiding under police protection. In response to the death threats he received in 1989, the UK expelled 30 Iranian nationals, citing security concerns, and asked UK citizens to leave Lebanon for fear of kidnapping.

Also in 1989, a bomb exploded near the British consulate in Jal al-Dib, north of Beirut. While no consulate staff were injured and a UK official said at the time that they did not believe the consulate was the target of the attack, some speculated that the bombing may have been linked to the Rushdie affair.

Meanwhile, the Rushdie controversy did indeed put the lives of the American and British hostages at risk. Their captors decided to freeze their release and to link their fate to the positions adopted by the West with regard to The Satanic Verses.

West Beirut was in a frenzy, with one Iranian-linked group delivering a message to the Beirut bureau of AFP threatening to “take revenge against all those who took part in strong and ferocious campaigns against Islam.”

In the end, the hostages were not dragged into the affair. Most of them were released in 1991 after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

After Iran adjusted its stance on Rushdie in 1998 under reformist president Mohammad Khatami to neither endorse nor discourage his murder rather than openly advocate for it, Hezbollah seemingly followed Iran’s revised policy, although the party continued to weigh in against Rushdie from time to time. After Britain's Queen Elizabeth II knighted Rushdie in 2007, Hezbollah sent a letter of protest to the British Embassy in Beirut.

While there has been relative quiet on the matter of Rushdie’s case in Lebanon since then and many of his books are available in the country, the ban on The Satanic Verses remains.

Foreign books in Lebanon are generally imported by one of two distributors, Ciel and Antoine. Local publishers require government licenses to print books, and can face censorship before a book is printed, but for foreign books censorship takes the form of an order from General Security blocking the importation of a particular title. There is no complete, publicly available list of banned books.

A General Security spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment. A Ciel representative said he was unable to comment without authorization, which was not forthcoming.

A bookstore owner who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of repercussions confirmed that The Satanic Verses remains banned in Lebanon as of this week, although he was unable to confirm the reason General Security does not allow the title. The rest of Rushdie’s titles are allowed for import.

He decried book bans for keeping “valuable information” from people and noted that censorship may even be counterproductive from the point of view of the censors’ own objectives as bans can spark curiosity and “push people towards these topics.”

He recalled a quote from author Isaac Asimov, “Any book worth banning is a book worth reading.”

Sami Naufal, Antoine’s chairman, had a similar perspective: “Book bans are generally speaking ineffective since they provide an excellent marketing vehicle to the banned book and most people find one way or the other to get hold of a copy whether a hard one or an electronic one resulting in a much larger audience defeating the very aim of the ban itself.”

In Haret Hreik, in the free library once overseen by the late Lebanese Shia Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah, who was sometimes described in the Western media as a spiritual mentor for Hezbollah, four of Rushdie’s books sit on the shelves along with at least nine book-length works of commentary and criticism on his work, especially The Satanic Verses. The library has been noted for its willingness to carry work banned in Lebanon due to religious or political sensitivities.

Back in 1989 Fadlallah seemingly walked a tightrope, calling on Rushdie to “open a dialogue with people” offended by his work while shying away from directly criticizing Khomeini’s edict.

Some of the secondary material on Rushdie in the library is critical, but not all of it. Among the titles is a defense of Rushdie by Syrian intellectual Sadiq Jalal al-Azm. Azm was himself no stranger to controversy — he was briefly arrested in Lebanon in January 1970 over his book Critique of Religious Thought.

Additional reporting by Richard Salame