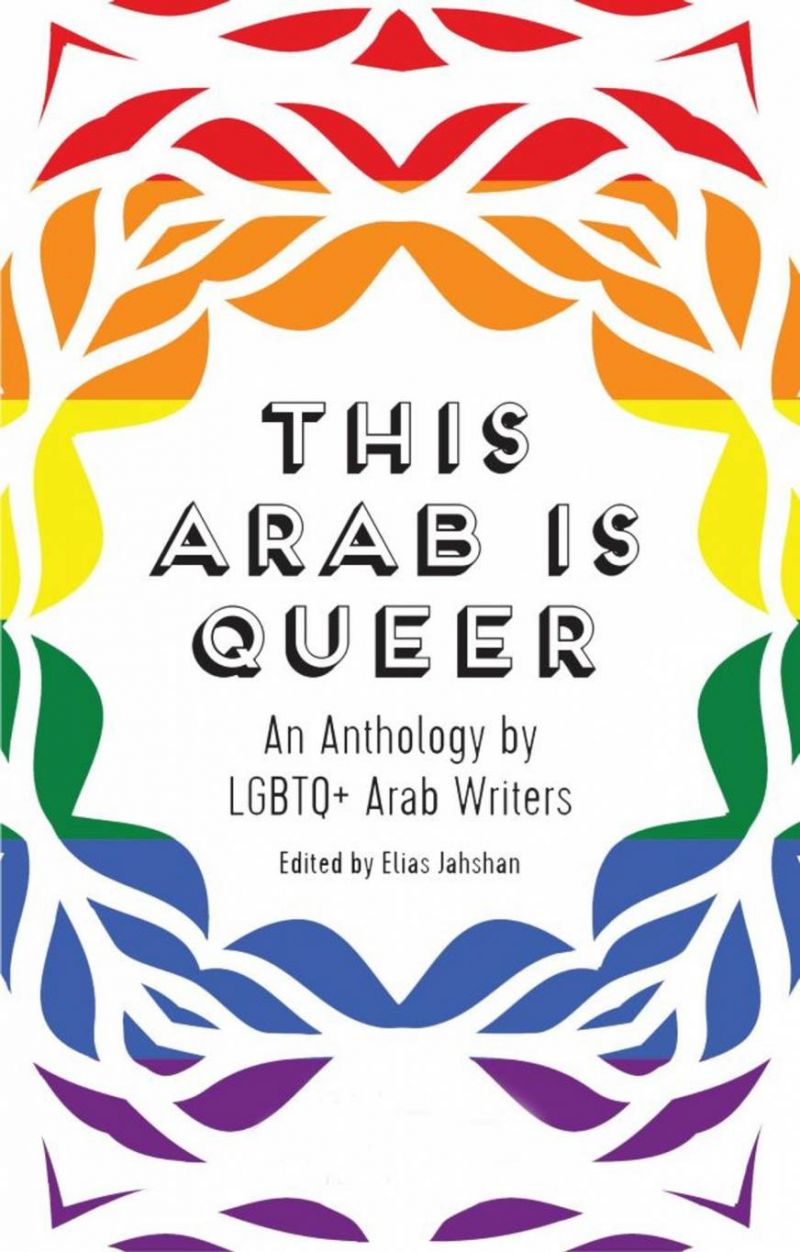

(Courtesy of Saqi Books)

When Jahshan realized it had not, his husband gave him a gentle nudge.

“‘Write that proposal, now,’ he said. ‘What have you got to lose?’”

He did, and “This Arab is Queer,” a labor of love and community, soon found a home at Saqi books, the independent Angl0-Lebanese publishing house. It was published two months ago, and has since won critical acclaim, with many saying that the book fills a gap that has existed for too long.

“This Arab is Queer” offers a multifaceted and nuanced look at both common issues (and traumas) and wildly differing personal experiences recounted by a wide array of contributors — not necessarily writers in the conventional sense, from different countries.

This anthology was born out of frustration that so much research, literature and news about the Arab queer community has been produced by non-Arabs. Its very existence might help alleviate the vexation of those who recognize themselves, or facets of themselves, in these stories.

“It wasn't really a light bulb moment. A few things led up to it,” Jahshan told L’Orient Today from his London home. “Daesh had their reign of terror in Iraq and Syria, and all those awful headlines appeared of them throwing gay men off the roof. It really affected me, even though I’m not Syrian or Iraqi, I felt a cultural connection to the queer community there. And I remember feeling really helpless, as an editor of a queer media outlet in Australia, on the other side of the world, not being able to tell these stories with the nuance that they deserved.”

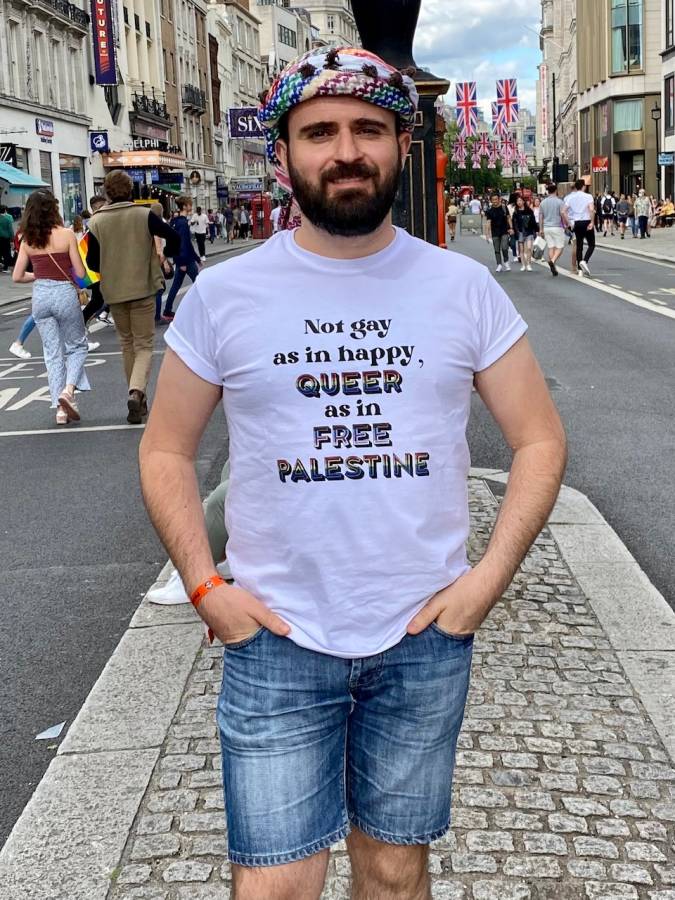

Elias Jahshan. (Courtesy Elias Jahshan)

Elias Jahshan. (Courtesy Elias Jahshan)

Jahshan stressed that he doesn’t think that Western mainstream media shouldn’t have covered these events.

“It was the way in which it was portrayed by the English language, really Western, media," he says. "It always had this element of a white savior complex, with either strong undertones or even blatant Islamophobia and racism running through it. It felt like the voices of the gay community in SWANA just weren't given the dignity and space they needed to tell their stories their own way.”

He remembers when the Egyptian regime raided a cinema where gay men purportedly met secretly, after which they were outed against their will and humiliated. While the incident was horrific in itself, Jahshan will never forget how it felt to see outed members of the queer community being spoken about and over, rather than them being able to share their own stories, even anonymously.

“It’s like our agency is being taken away from us,” he said. “For instance, in 2020, the EU, Canadian and British embassies in Baghdad started to raise the rainbow flags in solidarity with the queer community in Iraq. While their intentions were great, they did not liaise with the community itself, provoking homophobia throughout the country, which at some point got quite violent.”

“This Arab is Queer” was brought to life to remedy that, by moving away from the sensationalist, unsophisticated, even orientalist way of approaching the stories of this diverse community. It creates a space away from the white gaze.

For Lebanese novelist Rabih Alameddine, who has not shied away from including his experience of living as an Arab gay man in his award-winning novels, this anthology is “profoundly moving and uplifting.” It includes essays by known members of the queer Lebanese community, like Mashrou3 Leila frontman Hamed Sinno and activist, actor and storyteller Dima Mikhayel Matta, poet Omar Sakr and writer Tania Safia.

“Many white people have a hard time reconciling the fact that I’m both gay and Arab,” says Jahshan, who has a Lebanese mother and Palestinian father. This has been his experience since he moved to London. Growing up in Australia, he was alienated from all communities he belongs to.

“There was a family friend who was gay. Other than that I had no-one to compare myself to. White gay men tended to fetishize me or negatively pigeonhole the Arab part of my identity,” Jahshan says. “It just didn’t compute in their minds that I could be happy being both gay and Palestinian, as if that were an impossible concept!”

Fetishization is a theme that pops up more than once in the anthology.

In Tania Safi’s deeply personal story about growing up queer as a first-generation Lebanese-Syrian immigrant in Australia, and often visiting her homelands, she writes about discovering there was a term for that uneasy feeling that she couldn’t escape while being in a relationship with a white woman.

“She likes me because I’m Arab? This was just mind-blowing, because it had never happened before. A white lesbian who loved my Lebanese moustache and curly hair. But even then, naïve as I was, something didn’t feel right. I wasn’t aware of the concept of racialized fetishization, but I knew how it felt. On top of that, I suddenly had an answer as to why she wanted me – and realized that I had to stay that way to keep her.”

Not every story in the anthology confronts these concepts head-on. In one story, the queer identity of the writer is almost secondary. This is the biggest strength of the collection: rather than a collection of personal essays about Arabs who identify as queer, it’s an amalgam of stories, about small and big things, written by people who just happen to be Arab and queer.

Elias Jahshan. (Courtesy Elias Jahshan)

Elias Jahshan. (Courtesy Elias Jahshan)

Although he embraces all parts of his heritage with equal love, it’s the Palestinian part of Jahshan’s identity that tends to invite most scrutiny, and to be used against him — especially when he is targeted online for his outspoken and unwavering support for Palestine.

“I’ve had to deal with people’s uninvited comments about how gay rights are supposedly respected in Israel and the pink-washing tropes that go along with that,” Jahshan says. “You know, oh they throw gay men from rooftops in Gaza, equating ISIS’s reign of terror to Palestinians in Gaza. Or, when I just try to exist as a Palestinian, they tell me: “Why don't you try being gay in Saudi Arabia?”

Obviously Jahshan cares about the anthology being positively received, both because of the time and effort he put into it and the trust the writers placed in him, but what matters the most to him, he says, is having helped created something that he wished had existed when he was a young, conflicted man growing up.

“Just the loneliness I felt … It would have been a lot easier if this kind of book had come out when I was in my teens or my early 20s, when I started coming out,” he says. “It wasn’t about barely knowing other gay Arab men, who had to navigate as many different worlds, but also this idea of masculinity, what it meant in my Arab community but also as an out gay man.”

Just as he remembers the first time his identities organically converged — at a queer party in Sydney, where they played Arabic music and he could dance the way he would dance at the Arab weddings he was used to — it’s comforting to know that someone might pick up this book and feel less alone.

“Knowing that we created something unique, in which we tell our stories, on our terms,” he says, “a safe space where both ambiguity and nuance are embraced, with no orientalist white gaze intervening, created by our community, for our community — that is something no-one can ever take away from us.”