With the disappearance of places of worship, the Jewish community lost what allowed it to exist as a group. Now they manage as best we can. And they get creative. In the event of a death, a rabbi from abroad is called upon, since the last one left Lebanon in 1977. (Photo: rights reserved)

In a shopping center in the capital, three-year-old Eve* is restless. She climbs from one carousel to another, prancing around the wooden horses. She is younger than the other children around her. More reckless too.

From a distance, her mother worries for her. She could hurt herself. She could attract attention.

Her mother is Judith.* She was born in Beirut in the mid-1980s to a Jewish father and a Christian mother. She never knew Lebanon from the bygone days — a country where being Jewish was something normal, another trivial detail that no one dwelled on.

She grew up in a different country, where what was once called a “community” was reduced to a few dozen people at most. A country where to be Jewish, or even half Jewish as in her case, is to be condemned to silence — a sentence that unfolded as time went by.

Year after year, the fear of “making trouble” took precedence over everything else.

With her sparkling eyes and determined expression, Eve is still far removed from these concerns.

She only wants to have fun. Her levity appears to be in direct conflict with the anguish written all over her mother’s face.

But Judith has no doubt about it: not too long from now, these questions will catch up with her too.

Not because she chose to give her daughter a Jewish name. But because of her own experience, which has taught her that one cannot escape one’s origins, and even less so the eyes of others.

As a child, her family tried to keep it quiet.

“It was a secret,” she says. But then at school, her older sister Sarah* mistakenly revealed her father’s religion. “It was a big deal — it was traumatic,” Judith recalls.

A few years later, her sister was insulted by a friend in public.

“We were in Arabic class when he said to me: 'You, Jew, shut up, you’re not allowed to speak,’” says Sarah, who was expelled from school for three days after picking a fight.

The two sisters are haunted by memories of similar incidents in their childhood.

Looking at them separately, these incidents did not prevent them from working, getting married or starting a family. But taken together, they have contributed to a diffuse sense of unease and disconnect from the rest of society.

Until today, Judith doesn’t like to talk about “it.” But in Lebanon, where the first question asked is often related to one’s sectarian origins, she has no choice.

Avoiding the subject turns into an art of dodging.

She remembers her first meeting with her Christian in-laws, who immediately tried to “get into the details.”

“It's very important here for people to know ‘Enti min wein?’ (‘Where are you from?’). But when I tell them I’m just from Beirut, they are not convinced,” she said.

Faced with so many questions, Judith loses patience.

“What do you want me to say to them? I'm not going to tell them my whole story!” she snapped.

The Maghen Abraham Synagogue in Beirut, built in 1926, is now closed to the public. Its latest renovation, after the double explosion at the port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, was made possible by private funding. (Credit: Mohammad Yassine)

The Maghen Abraham Synagogue in Beirut, built in 1926, is now closed to the public. Its latest renovation, after the double explosion at the port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, was made possible by private funding. (Credit: Mohammad Yassine)

Twenty-seven 'Israelites'

Her story is that of many Jews who arrived in Lebanon in the 20th century.

Her father, born in Beirut in the early 1940s, came from a Jewish family of Algerian and Syrian origin who landed in Lebanon when it was a land of refuge for persecuted minorities in the Mediterranean basin.

Like some of his co-religionists, he never obtained Lebanese citizenship. But he was adamant about staying in the country, despite the successive departures of his brothers and sisters, the civil war, and everything else.

“He was stubborn because he loves Lebanon,” said Judith, in her thirties, who also asserts that she has no intention of leaving despite the difficult living conditions.

Of the 14,000 people who comprised Lebanon’s Jewish community at its peak, very few have resisted the temptation to leave.

Some 4,500 Jews are still registered on the electoral rolls, but the majority have died or left the country long ago, departing for Latin America, Europe, the United States, Canada or, on rare occasions, Israel.

Only 27 of them are still based in Lebanon as “Israelites,” the designation of Jews in the official registers, according to Nagi Zeidan, author of the French-language book Jews of Lebanon: from Abraham to the Present Day, History of a Disappeared Community.

Some people of Jewish origin are not even registered because they have been converted to other religions by marrying a spouse of a different confession, or they had never been naturalized, or they have a Christian or a Muslim father.

Those who have a general or specific interest in the history of Lebanese Jews know that in recent years, the doors of the community have been closing one by one.

There are those who do not want to talk anymore. Those who claim to have “nothing to say on the subject.” Those who don’t have the time. Or those who don’t want to hear any more about “those journalists who talk nonsense.”

The few who still agree to speak out do so anonymously, after having obtained all the necessary guarantees.

“They are scared to death,” says Zeidan.

But fear is not the only reason behind their reluctance. Many have grown weary of the whole issue.

“There’s an expression that goes: ‘You don’t stir shit, so you don’t smell it.’ We were born that way, it’s part of us, but we don’t care anymore,” said Sarah.

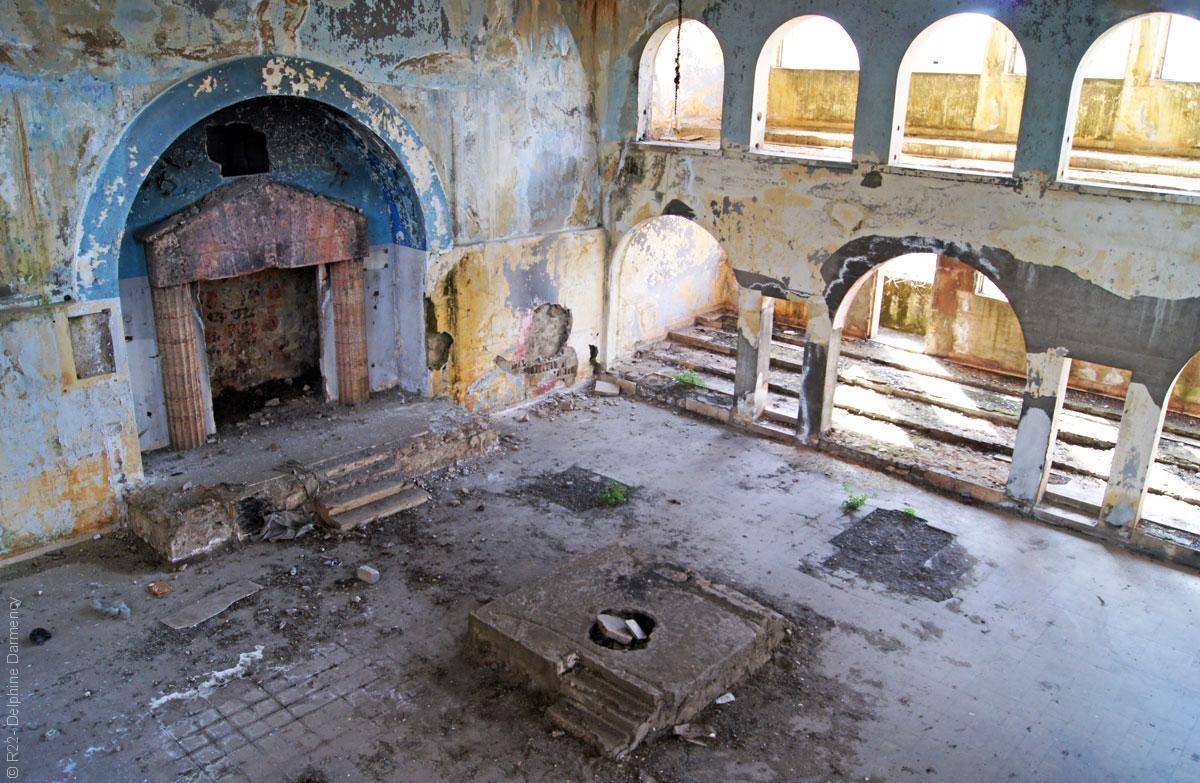

How not to let go, when everything else has fallen into disuse. In Tripoli, Aley, Hasbaya, Jbeil, Aley and Deir el-Qamar, entire neighborhoods were emptied in the space of a few years. The Stars of David have been removed.

Schools closed their doors. Synagogues were deserted. Cemeteries were abandoned. In Saida, where the presence of Jews dates back to the first century B.C., there is no longer any indication that the community was once one of the most flourishing in the area.

In the narrow streets of the old city, the Jewish memory has been erased. The last family, the Levys, left in the 1980s.

At the end of a dark alley, between a portrait of Yasser Arafat and a pile of electric wires, the old synagogue is hard to recognize.

For more than two decades, it has been occupied by families of refugees. On the walls, the flag of the Syrian opposition and suras from the Quran have covered up the old paintings. Only the locals know that this is the “hay al yahoud” (Jewish quarter).

The former synagogue in the old town of Saïda, now disused, is occupied by families of Syrian refugees. (Credit: Joseph Eid/AFP)

The former synagogue in the old town of Saïda, now disused, is occupied by families of Syrian refugees. (Credit: Joseph Eid/AFP)

A double life

In Beirut, where the bulk of the community has been concentrated since the middle of the 20th century, those who chose to stay saw their lives slip into a semi-clandestine state. Year after year, they have witnessed the disappearance of places of community life.

The Jews deserted their original neighborhood of Wadi Abu Jamil, where the community had been established since the end of the 19th century and moved to Christian areas starting in 1975-76.

The synagogue of Magen Abraham, inaugurated in 1926, was rehabilitated in 2014 thanks to private funding, and then again following the damage caused by the 2020 Beirut port explosion.

But like the rest of the neighborhood, managed by real estate company Solidere since the 1990s, it is now off limits to the public.

Even today, the remaining Jews of Lebanon are concentrated in the eastern neighborhoods of the capital or in its close suburbs.

Between sips of coffee, from her living room with a view of the Lebanese mountains, Diana* remembers the old days.

Born in Beirut in 1952, she knew life in Wadi Abu Jamil, Hebrew classes at the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Beirut, and religious holidays with her family.

Life then was sweeter, but it was not perfect.

Her childhood, too, is marred by bitter anecdotes that reflect the dormant anti-Jewish sentiment that has long permeated Lebanese society.

She remembers how her father’s friends used to refer to him as “al yahoud" (the Jew), or how, every Easter, the same stories would surface.

“The Christian children told me that I had crucified little Jesus. I wondered what I had done to be told this,” Diana recalled.

Founded in 1869, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, in Wadi Abu Jamil, was one of the private establishments of the Jewish community of Beirut. The children were educated there until the third, before being transferred elsewhere – often to the French Lycée or to a Catholic establishment. Partially destroyed, it was rebuilt in the 1950s (see photo). In the foreground, a metal fence separates the playground for boys and those for girls. (Credti: personal archives, Sélim Nassib)

Founded in 1869, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, in Wadi Abu Jamil, was one of the private establishments of the Jewish community of Beirut. The children were educated there until the third, before being transferred elsewhere – often to the French Lycée or to a Catholic establishment. Partially destroyed, it was rebuilt in the 1950s (see photo). In the foreground, a metal fence separates the playground for boys and those for girls. (Credti: personal archives, Sélim Nassib)

Despite the occasional hostility toward them, Jews lived in relative harmony with their environment until the 1970s and 1980s.

It was only in the 2000s, when she returned to settle down in Lebanon after having lived in Europe for a number of years, that Diana began to hide her identity.

“I had to protect myself. I understood how badly it was seen [to be Jewish],” she said.

Over the years, a new form of antisemitism, more virulent and fanned by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, gained ground.

“Because we were Jews, we were traitors,” she said.

She remembers a friend who, in the course of a conversation, went so far as to ask her how “Jews can afford to go to Long Beach Club, or to summer in Bhamdoun, if they are not financed by Israel.”

Living in these conditions is like leading a double life.

Jews who did not convert to other religions have to present themselves as Christians.

Those who spoke Arabic with a Syrian accent because of their family origins started to “speak like Christians.”

To go unnoticed, they are ready to do anything. Including changing their names: “Haïm” becomes “Victor,” “Abraham” becomes “Albert.”

At work, most of them hide their identity.

“The Jews here are hard, they have a shell. No matter how hard you knock on it, it doesn't open up,” said Sarah, who is sometimes annoyed by what she perceives as the collective resignation.

The weight of secrecy is most violent when it affects the family core. Sarah remembers an acquaintance of hers whose close relatives had Jewish-sounding names.

For a long time, she avoided the subject, fearing that she might cause offense. Then one day she said, “Don’t take this the wrong way, but are you Jewish?”

Silence. Troubled looks. Then this answer: “I don't know.”

Can one ignore something like this? Sarah asked for an explanation.

“We never talk about religion; we don’t practice it. I believe that my parents are Jewish, but I am not sure of it,” answered her interlocutor. Sarah offered access to the community’s records, but the answer was no.

Sometimes it’s easier not to know.

Resourcefulness

As the places of worship disappeared one by one, the community has lost what allowed it to exist as a group.

So, to keep the bare minimum, they had to make do with what they have. Some get a little creative.

When a death occurs, a rabbi from abroad is called, since the last one left the country in 1977. He officiates the prayer remotely, by video, from the United States, Canada, or Australia.

When people want to gather to pray, they do so in a house rather than in a synagogue, “where many no longer dare to show their faces for fear of being seen,” said Zeidan.

And when the necessary quorum for collective prayer (the “minyan,” a minimum of 10 adult men required) is not possible, acquaintances are asked to come and attend the service, in silence, to allow those who wish to do so to perform prayers.

This Lebanese-style resourcefulness makes it possible to maintain the rites, at home, far from the public eye.

But it hinders the survival of a collective culture, the one that cements a sense of belonging to the group.

“I miss family celebrations, Hanukkah, Purim, Rosh Hashanah, Pesach, Kippur... all that,” Diana said.

It also complicates the transmission of customs and traditions from one generation to the next.

“To nurture a spirituality, you have to have something to give: here, there is no synagogue, nothing that can help you raise your spirituality,” according to Sarah.

The Hebrew prayers have been the first victims of this slow death.

“As children, we used to laugh when my father recited the prayers. There was something solemn about it. And then it was in Hebrew, which he always refused to teach us: it was useless,” Judith recalled.

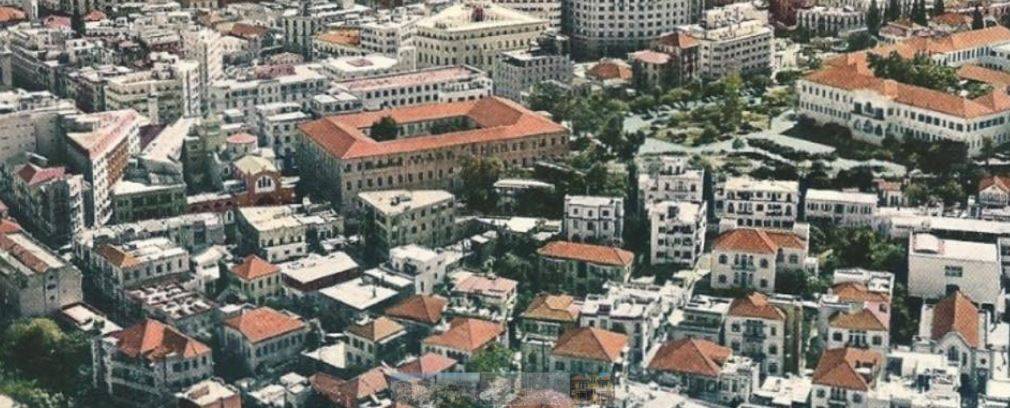

An aerial view of the Wadi Abu Jamil neighborhood in the 1950s. (Credit: Nagi Zeidan archives)

An aerial view of the Wadi Abu Jamil neighborhood in the 1950s. (Credit: Nagi Zeidan archives)

By coiling into themselves in the private, Jews have gradually distanced themselves from everything related to the public sphere.

On the surface, nothing has changed since Lebanon recognized the community as one of the country’s 18 official communities.

The authorities cling to the historical position that has long made the country an exception in the region: Jews have the same rights as all other citizens.

In Parliament, they are represented by an MP for minorities, for whom the Syriac Catholics and Orthodox, Chaldeans, Assyrians, Copts and Latins also vote.

Since 1911, the community has also had a civil status law allowing it to vote for a president — a rare occurrence at the time — as Christians and Muslims were only recognized by the state on a religious level, as opposed to religious and civil status.

Until today, the communal council, composed of five members, is elected every five years. Its chairman, Izaac Arazi, and his vice-chairman, Samo Behar, are responsible for day-to-day affairs — from the maintenance of cemeteries to the renovation of certain synagogues, to the protection of the most vulnerable.

80 / 5,000 Translation results The old synagogue of Bhamdoun, now abandoned. (Credit: Mohammad Yassine)

80 / 5,000 Translation results The old synagogue of Bhamdoun, now abandoned. (Credit: Mohammad Yassine)

But the community, which has never been very political, remains in the background.

Historically, it has never had the weight of other minorities. It never had its own political party, and it has long remained on the sidelines of conflicts.

Jews used to participate in national elections, for example, to elect Christian representatives, notably from the Kataeb, who presented themselves as defenders of minorities.

Since the 2000s, however, the withdrawal from public life has been almost total. During the Oct.17, uprising, during elections, few dared to speak out.

“I have never heard a Jew say he was going to vote. So, either they vote in secret, or they don’t,” explained Judith, who still does not have Lebanese nationality, although she applied for it after she got married and converted to Christianity.

She and her sister have carried on only a few family traditions. The “kebbeh yahoudyieh,” a Jewish dish handed down by her grandmother. A card prepared by the children for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. And a few words of Hebrew, just to be able to sing “Happy Birthday” to their grandfather.

But if the Lebanese Jewish identity has been emptied almost entirely of its religious and communal component, the feeling of belonging remains.

“What Jews have experienced throughout history, from pogroms to the Holocaust, is part of me. Even though we weren’t directly affected, that’s what makes me Jewish,” Diana said.

*Names have been changed due to privacy concerns.

This article was originally published in French in L'Orient-Le Jour. Translation by Sahar Ghoussoub.