Egyptian vocalist Ramy Essam in the music video for Mafi Mafi (Khod), his collaboration with Lebanese filmmaker-video journalist Tariq Keblaoui, sympathetic with Lebanon's 2019 popular demonstraions against the political class. (video grab)

The intro begins by listing a series of problems Lebanon is facing: “There’s no water, there’s no food, no work, no internet, no lights, no power, nothing, nothing (Mafi Mafi), there’s no fuel, there’s no gas, no medicine, no safety, no money, no tourism, nothing, nothing (Mafi Mafi).”

The song united a shared history of rebellion from different countries in the same region. Essam had penned a song that became the best-known anthem of the Egyptian uprising of 2011. He was arrested twice between 2011 and 2014 and is now living in exile.

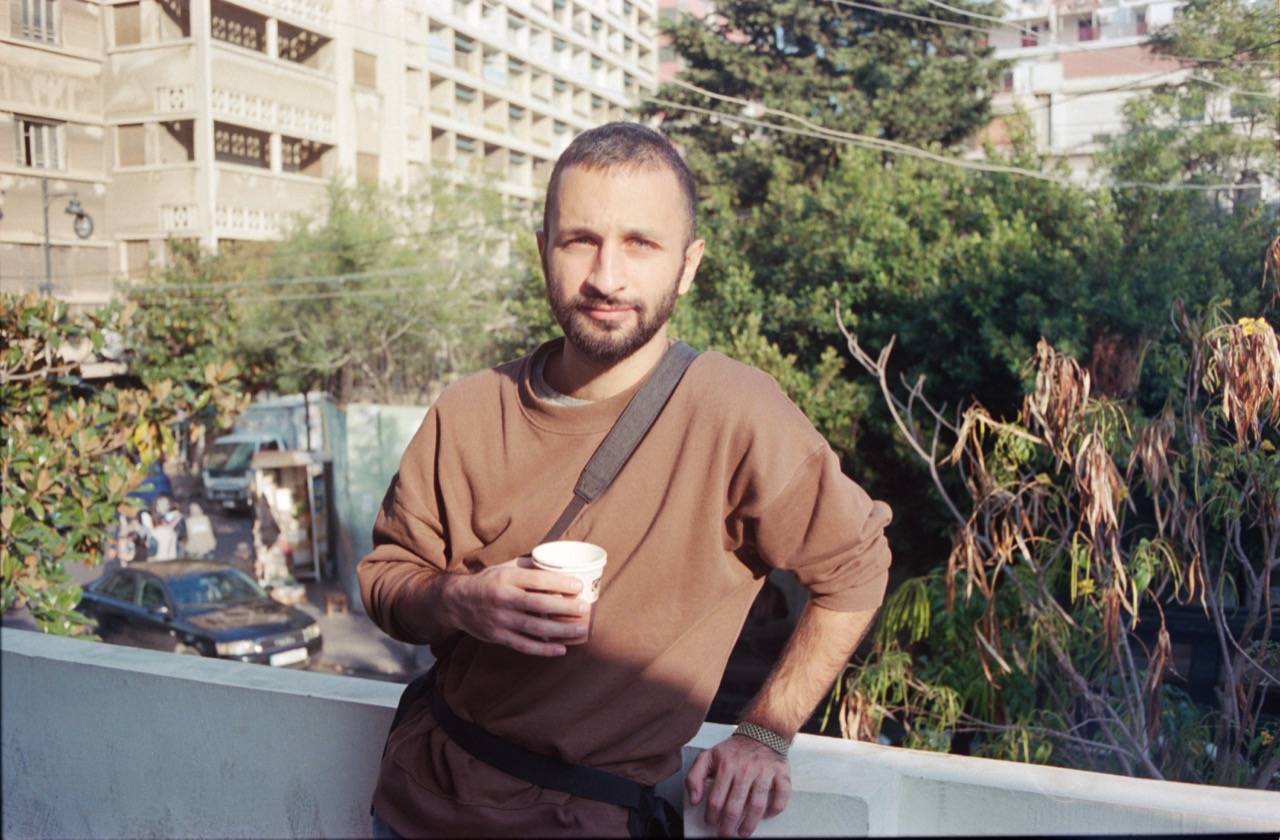

Lebanese filmmaker and video journalist Tariq Keblaoui (Photo: Amal Ghamlooch)

Lebanese filmmaker and video journalist Tariq Keblaoui (Photo: Amal Ghamlooch)

In his work as journalist and filmmaker, Keblaoui found himself on the streets every day, capturing the events of Lebanon’s 2019 thawra (revolution), amidst the violent crackdowns he and other protesters endured at the hands of the government. Keblaoui also barely survived the Beirut port blast in 2020, in the aftermath of which he continued to shoot videos and publish content via several news outlets, including CNN.

“I had the feeling that I really would love to do something for Lebanon, especially after my song Ahed El Ars (Era of the Pimp) was being played by the people during protest in Lebanon,” began Essam, who visited Lebanon for the first time in 2016. “I was so amazed and proud that my track is there, [played by] people that don't really know who I am.”

Watching the Lebanese people revolt from a distance, Essam felt compelled to utilize his talents in support of the movement and the people fighting against a regime they accused of exploiting them for decades.

“I felt that if I [create] something just by myself, it will not be authentic,” explained Essam about his physical absence from the scene in Lebanon. “I needed to have a local collaborator to make [the project] really reach the people.”

This is when he reached out to his friend, Ganzeer, a pseudonym used by an Egyptian artist who gained international fame following the 2011 Egyptian revolution. Ganzeer connected with Kebloui via Instagram, who later put Essam in touch with Samir Skayni, a co-writer of the song.

“We had this bond from the beginning,” recalled Essam.

The trio would sit together, virtually, for hours, in what Essam referred to as “beautiful and healthy workshops,” collectively writing the lyrics to Mafi Mafi (Khod). The song itself is an excellent mix of Egyptian and Lebanese dialects and local vernacular, which ultimately give a unique personality to a tune born out of shared, bittersweet trauma that was experienced by different individuals from different countries, continents even.

“Trauma bonding, do you know this expression? I felt like we were able to trauma bond in that way because we both totally get it,” said Keblaoui. “Two different versions of oppression, of living under oppressive systems, but the effect is the same, the anger is the same, the message is pretty much the same as well.”

The catalyst for what is now known as the Arab Spring was Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor providing for a family of six. In response to the confiscation of his wares and the harassment he endured from a municipal official and her aides, he set himself on fire in December, 2010, in an act of defiance against the government.

Following Bouazizi’s death in January, public anger and violence intensified in the country, forcing then-president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to step down after 23 years in power and flee the country. The success of the Tunisian protests inspired a series of unprecedented mass demonstrations against corruption, political repression and poverty in several Arab countries, including Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Syria and Bahrain, resulting in either the deposition of rulers or protracted civil conflicts.

Protests in Egypt began on Jan. 25, 2011, organized by youth groups, mostly independent of Egypt’s established opposition parties. Protesters took hold in the capital and several cities around the country, demanding then-president Hosni Mubarak step down immediately and make way for free elections and a more democratic state. The Mubarak regime resorted to extreme violence as the protests gained strength, resulting in hundreds of injuries and deaths. After almost three weeks, Mubarak stepped down, leaving the Egyptian military in control of the country.

“The pain that we share in our region is exactly the same. When I [visited] Beirut for the first time, from the crowd, the busy streets, the pain, the corruption, from all the good and the bad, everything we share is very similar, especially when it comes to the younger generations,” said Essam. “They are sharing the same art, the same alternative music, underground cultures and social media has helped that happen.”

Arab countries share an entire culture, a history and a language — though some differences in dialect and quirks particular to each country do exist. There is great diversity in the region. However, the similarities found in both the struggles endured and the brilliance produced in countries across both continents is often lost to the media — be it Western or regional coverage — or in a global politics that frames Arab people as inherently prone to conflict.

“About 98 percent of the shots in the video are ones that I've taken, whether on Aug. 4, 2020, or shots I took around Beirut in the past couple of weeks to a year,” explained Kebaloui.

Both Essam and Keblaoui wanted to represent “the chaos, the absurdity and the confusion” suffocating the Lebanese people since the protests erupted in Beirut almost three years ago.

As a freelance journalist, especially since the blast and in the midst of the economic crisis, Kebaloui found it challenging to capture the chaotic and painful reality of the country and relay to an international and local audience just how dire Lebanon's circumstances are.

A scene from the music video for Mafi Mafi (Khod), sympathetic with Lebanon's 2019 popular demonstraions against the political class. (video grab)

A scene from the music video for Mafi Mafi (Khod), sympathetic with Lebanon's 2019 popular demonstraions against the political class. (video grab)

“The reason why we decided to make it a very multi-mixed-media video of shots, graphics and archival footage is because we wanted to not just use footage from the streets, but to also just give a very emotional representation of what we're going through,” Keblaoui told L’Orient Today.

Keblaoui’s work prior to his collaboration with Essam was from a more classic filmmaker approach, he said. From working on his documentaries or films, he was used to preparing shot lists, abiding by specific layouts, casting actors, directing entire crews; meticulous, organized and scripted work.

“This is the first time I challenged myself, because I really wanted to try being as experimental as possible. Between me and Rami and the graphic designer, we came up with more or less a storyboard of what each scene is trying to capture,” explained Keblaoui about his process.

“All of it was kind of done on the fly, me going around on the back of a motorcycle, shooting billboards, gas stations, other things I found. It was very improvised in that sense.”

He would then spend almost two weeks animating graphics sent to him by Gaella Lattouf, the graphic designer who worked on this project, experimenting with frames, jump cuts, switching colors, transitions and textures. Essam and Skayni were part of that process too, at least creatively. After each scene Keblaoui completed, he’d send it to their group chat and the three of them would brainstorm together, with enough feedback to fuel Keblaoui back into another editing frenzy.

“The graphics I was using were destroying my laptop. So it was like using this machine that's not even cooperating. And I'm just adding layers and layers and layers of different effects,” he reminisced. “I became obsessive about the project. Every time I was around my friends, I put my laptop out and start working… Whenever I have a passion towards the video, I just go all in.”

Two minutes into the song and all the sequences, compiled with juggling his other jobs and sleep-deprivation, Keblaoui said he began to lose his mind.

“My friend told me that she felt like the more I'm working on this video, the more my mind is deteriorating, which gave me an idea for the ending of the video,” he said.

A scene from the music video for Mafi Mafi (Khod), sympathetic with Lebanon's 2019 popular demonstraions against the political class. (video grab)

A scene from the music video for Mafi Mafi (Khod), sympathetic with Lebanon's 2019 popular demonstraions against the political class. (video grab)

In the final seconds of the video, Keblaoui created an ultimate climax of chaos and deterioration by mashing six different layers of video, black, white and color mixed together combining a dizzying number of shots. The end of the video is a nonlinear fast rewind of the entire clip with bits of fast-forwarded animation over it.

“I saw the footage, I was talking to [Keblaoui] about it and I thought that he used clips from our revolution. But his answer was no,” said Essam.

“We had this group of people that were documenting the streets [in Egypt], their name was Mosireen. They played the same role as Megaphone News in Lebanon. I asked [Keblaoui] if he knew about them, he also said no.”

It became clear to Essam that Keblaoui did not pull any footage from the revolution in Egypt, nor was he trying to remake any of those scenes from Tahrir Square in 2011.

“He wasn’t repeating an experience that happened in Egypt. It was real. It also felt like being born again, in a different place, with different people because we are exactly the same,” explained Essam with an almost melancholic nostalgia.

Like most of his songs, the lyrics to Mafi Mafi (Khod) are viciously critical of the regime, but with added layers of satire and comedic irony, achieved through the use of popular phrases coined during the protests and directed at members of the government. The effect is a breakdown of the stiff barrier between ruler and subject. The people, it seems to say, are no longer scared of this powerful entity. They are now singing songs in a dialect and parlance of their own creation, regaining control from their oppressors.

A still from Jehane Noujaim's 2013 documentary 'The Square,' showing Ramy Essam singing in Tahrir Square. (Noujaim Films)

A still from Jehane Noujaim's 2013 documentary 'The Square,' showing Ramy Essam singing in Tahrir Square. (Noujaim Films)

During the Egyptian revolution, Essam would sing his song “Irhal” (leave), which urged then-president Mubarak to resign, in front of hundreds of thousands of protesters. It was recognized as the song of the revolution and was selected by Time Out magazine as the third-most world-changing song of all time. Essam was later arrested twice, enduring long hours of torture at the hands of the regime. After his second arrest in 2014, he decided to leave Egypt and take up refuge in Sweden, also in an attempt to escape his military service.

“All my music was banned from radios and TVs, I was banned from performing in any festivals or venues. [The government] was ruining my life in all ways. I was also so close to being forced into my military service. It's just against my morals and principles,” Essam told L’Orient Today. “My plan was to leave Egypt for three years so I can turn 30 years old and then go back home again.”

However, in 2018, after he released a song titled “Balaha”, or date, a slang term referring to a character in a popular Egyptian film who is a liar and often directed at President Abdel-Fattah el Sisi by his critics, eight people were arrested — some with little or no connection to Essam, including the director of the song’s video Shady Habash, who died in custody after being jailed and allegedly neglected by the state for 800 days. The Egyptian government revoked Essam’s passport, and he lost his Egyptian citizenship.

On the night of October 17, 2019, as soon as news of the protests came out and the tires were burning, Keblaoui, who happened to have his camera on him, just started filming. Every day onward, he would go down to the streets, film and post his footage online.

“I just didn't care who used it. I didn't care about copyrights. I didn't care if they credited me. I really didn't care, I just wanted my footage to be out there, for it to be made [available] to the public and for it to circulate. And that, I feel, was my duty, in terms of my contribution to the revolution,” said Keblaoui, whose footage would later be used by CNN, Megaphone News and other media outlets.

And then came the blast.

“I was a couple of meters away from perhaps certain death, or at least severe mutilation. I just happened to leave a room that was completely obliterated. I didn't leave the room knowing that I was going to be safe, I just left because I heard the first explosion,” recalled Keblaoui painfully.

Within an hour after the explosion, he received a call from the CNN office in Beirut, whose cameraman had been blown off his motorcycle, asking Keblaoui to go down to the streets and film.

“I had to film and edit approximately, without exaggeration, 20 hours a day, getting sometimes one-to-two hours of sleep. So I had to work while processing an extremely traumatic incident that I couldn't even make sense of until three days later.”

“There were just so many similarities in terms of what was happening on the ground [in Egypt and Lebanon], the sudden bursts of hope, and then also like the collapse of hope. But coming into the elections, the effect of the [October 17] revolution is clear,” said Keblaoui. “The glass ceiling that has protected these political names that could never be named or [has] never been tackled can actually be challenged.”

Contrary to the slight political breakthrough in Lebanon post-elections, with Parliament welcoming 13 new independent and opposition members, Essam told L’Orient Today that the political scene in Egypt has taken several steps backward since the Arab Spring in 2011.

“We are totally stuck with the military regime that is even more powerful now than in Mubarak’s era. But the revolution’s impact that I still can see is our youth,” said Essam.

Today’s younger generation in Egypt has managed to challenge the government on an international scale. From cases of sexual harassment, to political oppression and all pressing issues in between, the youth have pushed against a suffocating regime, all while also creating political and alternative art in various forms that has reached people and connected them globally.

“This is what the government could not kill, could not repress and will never be able to do. If the revolution couldn't take away the regime, it at least started to change the people's way of thinking,” said Essam.

“One of the biggest lessons we learned is that to change 65 years of government corruption and a military regime, it will not only take 10 years.

Everybody wished for this revolution to succeed. There are seeds planted in all of us and these seeds are growing and we will harvest them someday.”

When Essam released Mafi Mafi (Khod), something about an Egyptian singer chronicling Lebanon’s severe freefall in a song that mixed Egyptian and Lebanese dialect, criticizing the miserable state of the country using copious amounts of satire and telling the government to “get fucked,” some people were confused. Why him? Why Lebanon? How does he relate?

“The more I travel the world, in our region, and even in the States or in Europe, or anywhere else, I find that the people’s pain everywhere is the same,” said Essam. “It’s still very difficult being exiled, especially when it was not my choice to begin with, but that doesn’t make me less connected to Egypt or my people… As an artist, I feel that I have a responsibility to do something. But of course, doing it in the right way, with local artists and collaboration.”

“I think it's really hard to calculate how much change art can bring to society on a quantifiable level. But the fact remains that art does bring so much inspiration to people, brings new conversations, new memes, new ways of thinking – about in our context, oppression,” explained Keblaoui, pondering on the impact of art and music in times of crisis.

“When [Essam’s] song became so popular in the Lebanese revolution, it becomes ingrained into your mind; you start to look at the government no longer as this scary, oppressive monster. It's more just like a pathetic worm, a thing that is worth mocking more than anything else. And that's empowering to people.”

Ramy Essam after being arrested and tortured in Egypt. (Photo: The Times of London/ Salma Said)

Ramy Essam after being arrested and tortured in Egypt. (Photo: The Times of London/ Salma Said)